A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

An acid is a molecule or ion capable of either donating a proton (i.e. hydrogen ion, H+), known as a Brønsted–Lowry acid, or forming a covalent bond with an electron pair, known as a Lewis acid.[1]

The first category of acids are the proton donors, or Brønsted–Lowry acids. In the special case of aqueous solutions, proton donors form the hydronium ion H3O+ and are known as Arrhenius acids. Brønsted and Lowry generalized the Arrhenius theory to include non-aqueous solvents. A Brønsted or Arrhenius acid usually contains a hydrogen atom bonded to a chemical structure that is still energetically favorable after loss of H+.

Aqueous Arrhenius acids have characteristic properties that provide a practical description of an acid.[2] Acids form aqueous solutions with a sour taste, can turn blue litmus red, and react with bases and certain metals (like calcium) to form salts. The word acid is derived from the Latin acidus, meaning 'sour'.[3] An aqueous solution of an acid has a pH less than 7 and is colloquially also referred to as "acid" (as in "dissolved in acid"), while the strict definition refers only to the solute.[1] A lower pH means a higher acidity, and thus a higher concentration of positive hydrogen ions in the solution. Chemicals or substances having the property of an acid are said to be acidic.

Common aqueous acids include hydrochloric acid (a solution of hydrogen chloride that is found in gastric acid in the stomach and activates digestive enzymes), acetic acid (vinegar is a dilute aqueous solution of this liquid), sulfuric acid (used in car batteries), and citric acid (found in citrus fruits). As these examples show, acids (in the colloquial sense) can be solutions or pure substances, and can be derived from acids (in the strict[1] sense) that are solids, liquids, or gases. Strong acids and some concentrated weak acids are corrosive, but there are exceptions such as carboranes and boric acid.

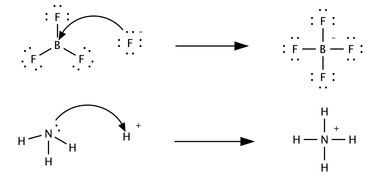

The second category of acids are Lewis acids, which form a covalent bond with an electron pair. An example is boron trifluoride (BF3), whose boron atom has a vacant orbital that can form a covalent bond by sharing a lone pair of electrons on an atom in a base, for example the nitrogen atom in ammonia (NH3). Lewis considered this as a generalization of the Brønsted definition, so that an acid is a chemical species that accepts electron pairs either directly or by releasing protons (H+) into the solution, which then accept electron pairs. Hydrogen chloride, acetic acid, and most other Brønsted–Lowry acids cannot form a covalent bond with an electron pair, however, and are therefore not Lewis acids.[4] Conversely, many Lewis acids are not Arrhenius or Brønsted–Lowry acids. In modern terminology, an acid is implicitly a Brønsted acid and not a Lewis acid, since chemists almost always refer to a Lewis acid explicitly as such.[4]

Definitions and concepts

Modern definitions are concerned with the fundamental chemical reactions common to all acids.

Most acids encountered in everyday life are aqueous solutions, or can be dissolved in water, so the Arrhenius and Brønsted–Lowry definitions are the most relevant.

The Brønsted–Lowry definition is the most widely used definition; unless otherwise specified, acid–base reactions are assumed to involve the transfer of a proton (H+) from an acid to a base.

Hydronium ions are acids according to all three definitions. Although alcohols and amines can be Brønsted–Lowry acids, they can also function as Lewis bases due to the lone pairs of electrons on their oxygen and nitrogen atoms.

Arrhenius acids

In 1884, Svante Arrhenius attributed the properties of acidity to hydrogen ions (H+), later described as protons or hydrons. An Arrhenius acid is a substance that, when added to water, increases the concentration of H+ ions in the water.[4][5] Chemists often write H+(aq) and refer to the hydrogen ion when describing acid–base reactions but the free hydrogen nucleus, a proton, does not exist alone in water, it exists as the hydronium ion (H3O+) or other forms (H5O2+, H9O4+). Thus, an Arrhenius acid can also be described as a substance that increases the concentration of hydronium ions when added to water. Examples include molecular substances such as hydrogen chloride and acetic acid.

An Arrhenius base, on the other hand, is a substance that increases the concentration of hydroxide (OH−) ions when dissolved in water. This decreases the concentration of hydronium because the ions react to form H2O molecules:

- H3O+

(aq) + OH−

(aq) ⇌ H2O(liq) + H2O(liq)

Due to this equilibrium, any increase in the concentration of hydronium is accompanied by a decrease in the concentration of hydroxide. Thus, an Arrhenius acid could also be said to be one that decreases hydroxide concentration, while an Arrhenius base increases it.

In an acidic solution, the concentration of hydronium ions is greater than 10−7 moles per liter. Since pH is defined as the negative logarithm of the concentration of hydronium ions, acidic solutions thus have a pH of less than 7.

Brønsted–Lowry acids

While the Arrhenius concept is useful for describing many reactions, it is also quite limited in its scope. In 1923, chemists Johannes Nicolaus Brønsted and Thomas Martin Lowry independently recognized that acid–base reactions involve the transfer of a proton. A Brønsted–Lowry acid (or simply Brønsted acid) is a species that donates a proton to a Brønsted–Lowry base.[5] Brønsted–Lowry acid–base theory has several advantages over Arrhenius theory. Consider the following reactions of acetic acid (CH3COOH), the organic acid that gives vinegar its characteristic taste:

- CH3COOH + H2O ⇌ CH3COO− + H3O+

- CH3COOH + NH3 ⇌ CH3COO− + NH+4

Both theories easily describe the first reaction: CH3COOH acts as an Arrhenius acid because it acts as a source of H3O+ when dissolved in water, and it acts as a Brønsted acid by donating a proton to water. In the second example CH3COOH undergoes the same transformation, in this case donating a proton to ammonia (NH3), but does not relate to the Arrhenius definition of an acid because the reaction does not produce hydronium. Nevertheless, CH3COOH is both an Arrhenius and a Brønsted–Lowry acid.

Brønsted–Lowry theory can be used to describe reactions of molecular compounds in nonaqueous solution or the gas phase. Hydrogen chloride (HCl) and ammonia combine under several different conditions to form ammonium chloride, NH4Cl. In aqueous solution HCl behaves as hydrochloric acid and exists as hydronium and chloride ions. The following reactions illustrate the limitations of Arrhenius's definition:

- H3O+

(aq) + Cl−

(aq) + NH3 → Cl−

(aq) + NH+

4(aq) + H2O - HCl(benzene) + NH3(benzene) → NH4Cl(s)

- HCl(g) + NH3(g) → NH4Cl(s)

As with the acetic acid reactions, both definitions work for the first example, where water is the solvent and hydronium ion is formed by the HCl solute. The next two reactions do not involve the formation of ions but are still proton-transfer reactions. In the second reaction hydrogen chloride and ammonia (dissolved in benzene) react to form solid ammonium chloride in a benzene solvent and in the third gaseous HCl and NH3 combine to form the solid.

Lewis acids

A third, only marginally related concept was proposed in 1923 by Gilbert N. Lewis, which includes reactions with acid–base characteristics that do not involve a proton transfer. A Lewis acid is a species that accepts a pair of electrons from another species; in other words, it is an electron pair acceptor.[5] Brønsted acid–base reactions are proton transfer reactions while Lewis acid–base reactions are electron pair transfers. Many Lewis acids are not Brønsted–Lowry acids. Contrast how the following reactions are described in terms of acid–base chemistry:

In the first reaction a fluoride ion, F−, gives up an electron pair to boron trifluoride to form the product tetrafluoroborate. Fluoride "loses" a pair of valence electrons because the electrons shared in the B—F bond are located in the region of space between the two atomic nuclei and are therefore more distant from the fluoride nucleus than they are in the lone fluoride ion. BF3 is a Lewis acid because it accepts the electron pair from fluoride. This reaction cannot be described in terms of Brønsted theory because there is no proton transfer. The second reaction can be described using either theory. A proton is transferred from an unspecified Brønsted acid to ammonia, a Brønsted base; alternatively, ammonia acts as a Lewis base and transfers a lone pair of electrons to form a bond with a hydrogen ion. The species that gains the electron pair is the Lewis acid; for example, the oxygen atom in H3O+ gains a pair of electrons when one of the H—O bonds is broken and the electrons shared in the bond become localized on oxygen. Depending on the context, a Lewis acid may also be described as an oxidizer or an electrophile. Organic Brønsted acids, such as acetic, citric, or oxalic acid, are not Lewis acids.[4] They dissociate in water to produce a Lewis acid, H+, but at the same time also yield an equal amount of a Lewis base (acetate, citrate, or oxalate, respectively, for the acids mentioned). This article deals mostly with Brønsted acids rather than Lewis acids.

Dissociation and equilibrium

Reactions of acids are often generalized in the form HA ⇌ H+ + A−, where HA represents the acid and A− is the conjugate base. This reaction is referred to as protolysis. The protonated form (HA) of an acid is also sometimes referred to as the free acid.[6]

Acid–base conjugate pairs differ by one proton, and can be interconverted by the addition or removal of a proton (protonation and deprotonation, respectively). The acid can be the charged species and the conjugate base can be neutral in which case the generalized reaction scheme could be written as HA+ ⇌ H+ + A. In solution there exists an equilibrium between the acid and its conjugate base. The equilibrium constant K is an expression of the equilibrium concentrations of the molecules or the ions in solution. Brackets indicate concentration, such that means the concentration of H2O. The acid dissociation constant Ka is generally used in the context of acid–base reactions. The numerical value of Ka is equal to the product (multiplication) of the concentrations of the products divided by the concentration of the reactants, where the reactant is the acid (HA) and the products are the conjugate base and H+.

The stronger of two acids will have a higher Ka than the weaker acid; the ratio of hydrogen ions to acid will be higher for the stronger acid as the stronger acid has a greater tendency to lose its proton. Because the range of possible values for Ka spans many orders of magnitude, a more manageable constant, pKa is more frequently used, where pKa = −log10 Ka. Stronger acids have a smaller pKa than weaker acids. Experimentally determined pKa at 25 °C in aqueous solution are often quoted in textbooks and reference material.

Nomenclature

Arrhenius acids are named according to their anions. In the classical naming system, the ionic suffix is dropped and replaced with a new suffix, according to the table following. The prefix "hydro-" is used when the acid is made up of just hydrogen and one other element. For example, HCl has chloride as its anion, so the hydro- prefix is used, and the -ide suffix makes the name take the form hydrochloric acid.

Classical naming system:

| Anion prefix | Anion suffix | Acid prefix | Acid suffix | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| per | ate | per | ic acid | perchloric acid (HClO4) |

| chloric acid (HClO3) | ||||

| ite | ous acid | chlorous acid (HClO2) | ||

| hypo | ite | hypo | ous acid | hypochlorous acid (HClO) |

| ide | hydro | ic acid | hydrochloric acid (HCl) |

In the IUPAC naming system, "aqueous" is simply added to the name of the ionic compound. Thus, for hydrogen chloride, as an acid solution, the IUPAC name is aqueous hydrogen chloride.

Acid strength

The strength of an acid refers to its ability or tendency to lose a proton. A strong acid is one that completely dissociates in water; in other words, one mole of a strong acid HA dissolves in water yielding one mole of H+ and one mole of the conjugate base, A−, and none of the protonated acid HA. In contrast, a weak acid only partially dissociates and at equilibrium both the acid and the conjugate base are in solution. Examples of strong acids are hydrochloric acid (HCl), hydroiodic acid (HI), hydrobromic acid (HBr), perchloric acid (HClO4), nitric acid (HNO3) and sulfuric acid (H2SO4). In water each of these essentially ionizes 100%. The stronger an acid is, the more easily it loses a proton, H+. Two key factors that contribute to the ease of deprotonation are the polarity of the H—A bond and the size of atom A, which determines the strength of the H—A bond. Acid strengths are also often discussed in terms of the stability of the conjugate base.

Stronger acids have a larger acid dissociation constant, Ka and a lower pKa than weaker acids.

Sulfonic acids, which are organic oxyacids, are a class of strong acids. A common example is toluenesulfonic acid (tosylic acid). Unlike sulfuric acid itself, sulfonic acids can be solids. In fact, polystyrene functionalized into polystyrene sulfonate is a solid strongly acidic plastic that is filterable.

Superacids are acids stronger than 100% sulfuric acid. Examples of superacids are fluoroantimonic acid, magic acid and perchloric acid. The strongest known acid is helium hydride ion,[7] with a proton affinity of 177.8kJ/mol.[8] Superacids can permanently protonate water to give ionic, crystalline hydronium "salts". They can also quantitatively stabilize carbocations.

While Ka measures the strength of an acid compound, the strength of an aqueous acid solution is measured by pH, which is an indication of the concentration of hydronium in the solution. The pH of a simple solution of an acid compound in water is determined by the dilution of the compound and the compound's Ka.

Lewis acid strength in non-aqueous solutions

Lewis acids have been classified in the ECW model and it has been shown that there is no one order of acid strengths.[9] The relative acceptor strength of Lewis acids toward a series of bases, versus other Lewis acids, can be illustrated by C-B plots.[10][11] It has been shown that to define the order of Lewis acid strength at least two properties must be considered. For Pearson's qualitative HSAB theory the two properties are hardness and strength while for Drago's quantitative ECW model the two properties are electrostatic and covalent.

Chemical characteristics

Monoprotic acids

Monoprotic acids, also known as monobasic acids, are those acids that are able to donate one proton per molecule during the process of dissociation (sometimes called ionization) as shown below (symbolized by HA):

- HA (aq) + H2O (l) ⇌ H3O+ (aq) + A− (aq) Ka

Common examples of monoprotic acids in mineral acids include hydrochloric acid (HCl) and nitric acid (HNO3). On the other hand, for organic acids the term mainly indicates the presence of one carboxylic acid group and sometimes these acids are known as monocarboxylic acid. Examples in organic acids include formic acid (HCOOH), acetic acid (CH3COOH) and benzoic acid (C6H5COOH).

Polyprotic acids

Polyprotic acids, also known as polybasic acids, are able to donate more than one proton per acid molecule, in contrast to monoprotic acids that only donate one proton per molecule. Specific types of polyprotic acids have more specific names, such as diprotic (or dibasic) acid (two potential protons to donate), and triprotic (or tribasic) acid (three potential protons to donate). Some macromolecules such as proteins and nucleic acids can have a very large number of acidic protons.[12]

A diprotic acid (here symbolized by H2A) can undergo one or two dissociations depending on the pH. Each dissociation has its own dissociation constant, Ka1 and Ka2.

- H2A (aq) + H2O (l) ⇌ H3O+ (aq) + HA− (aq) Ka1

- HA− (aq) + H2O (l) ⇌ H3O+ (aq) + A2− (aq) Ka2

The first dissociation constant is typically greater than the second (i.e., Ka1 > Ka2). For example, sulfuric acid (H2SO4) can donate one proton to form the bisulfate anion (HSO−

4), for which Ka1 is very large; then it can donate a second proton to form the sulfate anion (SO2−

4), wherein the Ka2 is intermediate strength. The large Ka1 for the first dissociation makes sulfuric a strong acid. In a similar manner, the weak unstable carbonic acid (H2CO3) can lose one proton to form bicarbonate anion (HCO−

3) and lose a second to form carbonate anion (CO2−

3). Both Ka values are small, but Ka1 > Ka2 .

A triprotic acid (H3A) can undergo one, two, or three dissociations and has three dissociation constants, where Ka1 > Ka2 > Ka3.

- H3A (aq) + H2O (l) ⇌ H3O+ (aq) + H2A− (aq) Ka1

- H2A− (aq) + H2O (l) ⇌ H3O+ (aq) + HA2− (aq) Ka2

- HA2− (aq) + H2O (l) ⇌ H3O+ (aq) + A3− (aq) Ka3

An inorganic example of a triprotic acid is orthophosphoric acid (H3PO4), usually just called phosphoric acid. All three protons can be successively lost to yield H2PO−

4, then HPO2−

4, and finally PO3−

4, the orthophosphate ion, usually just called phosphate. Even though the positions of the three protons on the original phosphoric acid molecule are equivalent, the successive Ka values differ since it is energetically less favorable to lose a proton if the conjugate base is more negatively charged. An organic example of a triprotic acid is citric acid, which can successively lose three protons to finally form the citrate ion.

Although the subsequent loss of each hydrogen ion is less favorable, all of the conjugate bases are present in solution. The fractional concentration, α (alpha), for each species can be calculated. For example, a generic diprotic acid will generate 3 species in solution: H2A, HA−, and A2−. The fractional concentrations can be calculated as below when given either the pH (which can be converted to the ) or the concentrations of the acid with all its conjugate bases:

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk