A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| History of California |

|---|

|

| Periods |

| Topics |

| Cities |

| Regions |

| Bibliographies |

|

|

After 1900, California continued to grow rapidly and soon became an agricultural and industrial power. The economy was widely based on specialty agriculture, oil, tourism, shipping, film, and after 1940 advanced technology such as aerospace and electronics industries – along with a significant military presence. The films and stars of Hollywood helped make the state the "center" of worldwide attention. California became an American cultural phenomenon; the idea of the "California Dream" as a portion of the larger American Dream of finding a better life drew 35 million new residents from the start to the end of the 20th century (1900–2010).[1] Silicon Valley became the world's center for computer innovation.

California demographics

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2024) |

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1840 | 8,000 | — | |

| 1850 | 120,000 | 1,400.0% | |

| 1860 | 379,994 | 216.7% | |

| 1870 | 560,247 | 47.4% | |

| 1880 | 864,694 | 54.3% | |

| 1890 | 1,213,398 | 40.3% | |

| 1900 | 1,485,053 | 22.4% | |

| 1910 | 2,377,549 | 60.1% | |

| 1920 | 3,426,861 | 44.1% | |

| 1930 | 5,677,251 | 65.7% | |

| 1940 | 6,907,387 | 21.7% | |

| 1950 | 10,586,223 | 53.3% | |

| 1960 | 15,717,204 | 48.5% | |

| 1970 | 19,953,134 | 27.0% | |

| 1980 | 23,667,902 | 18.6% | |

| 1990 | 29,760,021 | 25.7% | |

| 2000 | 33,871,648 | 13.8% | |

| 2010 | 37,253,956 | 10.0% | |

| 2020 | 39,538,223 | 6.1% | |

| Sources: 1850–2020 U.S. Census[2] * The 1850 statistics are corrected for lost census data in San Francisco, Santa Clara and Contra Costa Counties. California Indians were not counted before the 1870 census. | |||

California is now the most populous state in the United States. If it were an independent country, California would rank 34th in population in the world. California has had waves of immigration and emigration over the years. The first big wave was the California Gold Rush starting in 1848 of miners, businessmen, farmers, loggers, etc. as well as their many supporters.

There were fewer than 10,000 females in a total California population (not including Native Americans who were not counted) of about 120,000 residents in 1850. About 3.0% of the gold rush Argonauts before 1850 were female or about 3,500 female Gold Rushers, compared to about 115,000 male California Gold Rushers. Massive immigration from mostly other states continued throughout the nineteenth century.[3][4] California did not reach a "normal" male to female ratio of about one to one until the 1950 census. California for over a century was short on females.

The 1900 census showed emigrations down to "only" a 20% growth rate. The early 1900s showed a massive population increase of over 60% between 1900 and 1910. The population more than doubled again in the next 20 years by 1930. Foreign immigration largely ceased during the Great Depression, as immigration to the United States was held to a low of 23,068 per year by 1933, and many foreign workers were deported. There were not enough jobs to go around. After World War II and the Great Depression, there was a rapidly increasing buildup of United States workers in California as wartime industries boomed. Most of these workers were from other states as they settled in California and increased the California population to 10,586,223 by 1950. Immigration to the United States only started to increase significantly in 1946, when immigration to all of the United States was back up to 108,721 per year[3] The continuing prosperity and emigration from other states and immigration from other countries in the 1950s and 1970s almost doubled the California population again to 19,953,134 by 1970. The 1970–2010 population growth has still been substantial but has slowed to "only" about a 15% growth rate per decade. By 2010 the California population growth rate slowed slightly to 10%.

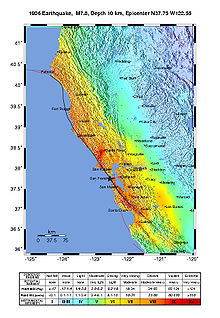

California earthquakes

Earthquakes in California are common occurrences since the state is traversed by six major strike-slip fault systems with hundreds of related faults, many of which are "brother faults" of the infamous San Andreas Fault that runs nearly the full length of California at the juncture of the Pacific Plate and the North American Plate. The fault systems include the Hayward Fault Zone, Calaveras Fault, Clayton-Marsh Creek-Greenville Fault, and the San Gregorio Fault. Significant blind thrust faults (faults with near vertical motion and no surface ruptures) are associated with portions of the Santa Cruz Mountains and the northern reaches of the Diablo Range and Mount Diablo. The California earthquake forecast gives a rough estimate of where the main earthquake zones in California are. Earthquake damage depends on what area is hit, how close to the surface the center of the earthquake is located, and its magnitude. Earthquake damage, for a given magnitude earthquake, to human structures depends on how well the buildings are built and what the structures are located on. Buildings on soft or filled-in soil suffer the most because they feel shock waves most strongly. Buildings on bedrock suffer less damage because the ground is firmer. Sometimes the ensuing fires, floods or tsunamis caused by the earthquake are often where the greatest damage occurs.

The 1906 San Francisco earthquake struck the city (then the largest in California) and nearby communities at 5:12 a.m. on Wednesday, April 18, 1906.[5] Devastating fires broke out in the city that lasted for several days, destroying about 28,000 buildings. As a result of the quake and fires, over 3,000 people died[6] and over 80% of San Francisco was destroyed. The death toll from the earthquake and resulting fire is the greatest loss of life from a natural disaster in California's history.

The most widely accepted estimate for the magnitude of the earthquake is a moment magnitude (Mw) or Richter magnitude (ML) of 7.8;[7] however, other values have been proposed, from 7.7 to as high as 8.25.[8] Shaking was felt from Oregon to Los Angeles, and inland as far as central Nevada.[9]

The San Francisco 1906 earthquake was caused by a rupture on the San Andreas Fault, a continental transform fault that forms part of the tectonic boundary between the Pacific Plate and the North American Plate. The fault is characterized by mainly lateral motion where the western (Pacific) plate moves northward relative to the eastern (North American) plate. The 1906 rupture propagated both northward and southward from its epicenter for a total of about 300 miles (480 km).[10] The San Andreas Fault runs the length of California from the Salton Sea in the south to Cape Mendocino to the north, a distance of about 810 miles (1,300 km). The earthquake ruptured the northern third of the fault for a distance of about 300 miles (480 km). The maximum observed surface displacement was about 20 feet (6.1 m); however, geodetic measurements show displacements of up to 28 feet (8.5 m) in some places.[11] The most recent analysis by the United States Geological Survey (USGS) shows that the most likely epicenter of the 1906 earthquake was very near Mussel Rock on the coast of Daly City, an adjacent suburb just south of San Francisco.[12]

A strong foreshock preceded the mainshock by about 20 to 25 seconds. The strong shaking of the main shock lasted about 42 seconds. The shaking intensity as described on the Modified Mercalli intensity scale reached VIII in San Francisco and up to IX in areas to the north like Santa Rosa, where destruction was devastating. There were decades of minor earthquakes – more than at any other time in the historical record for northern California – before the 1906 quake. They have been widely interpreted subsequently as precursory activity to the 1906 earthquake.[13]

| Significant California earthquakes | ||

|---|---|---|

| Earthquake | Magnitude | Fatalities |

| 1906 San Francisco | 7.8 | 3,000+1 |

| 1925 Santa Barbara | 6.3–6.8 | 13 |

| 1933 Long Beach | 6.4 | 115 |

| 1952 Kern County | 7.3 | 12 |

| 1971 San Fernando | 6.6 | 65 |

| 1989 Loma Prieta | 6.9 | 63 |

| 1994 Northridge | 6.7 | 60 |

| Notes: 1. The 1906 San Francisco earthquake caused so much damage that the authorities "lied" about the number of casualties. Subsequent research has shown that about 3,450 were "known" to have died. Some more were shot for looting.[citation needed] | ||

Due to a widespread practice by insurers to indemnify San Francisco properties from fire, but not earthquake damage, most of the destruction in the city was blamed on the fires. Some property owners deliberately set fire to damaged properties in order to claim them on their insurance. Capt. Leonard D. Wildman of the U.S. Army Signal Corps[14] reported that he "was stopped by a fireman who told me that people in that neighborhood were firing their houses… they were told that they would not get their insurance on buildings damaged by the earthquake unless they were damaged by fire. The insurance industry eventually paid out over $250,000,000 (the largest amount they paid out for the next 60 years) which significantly helped to rebuild the city."[15] Building standards of the original 1906 buildings had almost no earthquake resistance built in. Since 1906 earthquake standards have been steadily upgraded as damages caused by earthquakes are investigated. Unfortunately, a lot of older buildings do not meet today's standards, and it would typically cost too much to upgrade them. It was discovered in 1906 (again) that all masonry-type structures built of brick and un-reinforced concrete are resistant to fire but not earthquakes.[16] A detailed analysis of the city of San Francisco today estimates that an earthquake over 7.0 magnitude would completely destroy or seriously damage many sections of San Francisco and could possibly result in thousands of deaths.[16] Today in most communities, structures built to later earthquake standards would do well in all but the strongest earthquakes. The water mains and other infrastructure needed for fighting fires have all been upgraded but are yet untested.

California oil industry

California pioneers after 1848 discovered an increasing number of oil seeps—oil seeping to the surface, especially in Humboldt, Colusa, Santa Clara, and San Mateo counties, and in the asphaltum seeps and bituminous residues in Mendocino, Marin, Contra Costa, Santa Clara, and Santa Cruz counties. In southern California, large seeps in Ventura, Santa Barbara, Kern, and Los Angeles counties received the most attention.[17] Interest in oil and gas seeps was stirred in the 1850s and 1860s, becoming widespread after the 1859 commercial uses of oil were demonstrated in Pennsylvania. Kerosene quickly replaced whale oil for lighting, and lubricating oils became an essential product in the Machine Age. Other uses later in the 19th century included providing paving material for many roads and providing power for many steam locomotives and steam-powered shipping—replacing coal.

Oil became a major California industry in the 20th century with the discovery of new fields around Los Angeles and the San Joaquin Valley, and the dramatic explosion in demand for gasoline to fuel the rapidly growing number of automobiles and trucks now being produced. Most of the oil production in California began in the late 19th century.[17] At the turn of the century, oil production in California continued to rise at a booming rate. In 1900, the state of California produced 4 million barrels.[17] In 1903, California became the leading oil-producing state in the US, and traded the number one position back and forth with Oklahoma through 1930.[18] Production at the various oil fields increased to about 34 million barrels per year by 1904. By 1910 production had reached 78 million barrels. California drilling operations and oil production are concentrated primarily in Kern County, the San Joaquin Valley, and the Los Angeles Basin.

As of 2012, California was the nation's third most prolific oil-producing state, behind only Texas and North Dakota. In the past century, California's oil industry grew to become the state's number one GDP export and one of the most profitable industries in California.[19]

There is also some offshore oil and gas production in California, but there is now a moratorium on new offshore oil and gas leasing and drilling in California waters and a deferral of leasing in federal waters. These restrictions were imposed after a series of accidents in the 1969 Santa Barbara oil spill released oil into the Pacific Ocean.[20]

In 1920, oil production in California had expanded to 77 million barrels.[17] Between 1920 and 1930, new oil fields across southern California were being discovered with regularity, including Huntington Beach in 1920, Long Beach and Santa Fe Springs in 1921, and Dominguez in 1923.[17] Southern California had become the hotbed for oil production in the United States.

However, the development of increased oil production in California had consequences. The additional California oil fields, along with booming oil supplies in Texas and Oklahoma, put downward pressure on the price. In the 1930s the Texas Railroad Commission tried to take charge of allocating oil production among the states to keep prices from falling to a few pennies a barrel.

After a century, the San Joaquin Valley remains a major producer. The Kern County part of the valley in 2008 had over 42,000 producing oil wells that provided about 68% of the oil produced in California, 10% of the entire United States production, and close to 1% of the total world oil production. Add to that another producing 2,000 wells in Fresno County. If the valley were a state in its own right, it would rank behind Texas, Alaska, and Louisiana as the fourth largest oil producer state in the country.

| California oil production in 2005[21] | |

|---|---|

| State | Barrels/day |

| Louisiana | 1,463,000 |

| Texas | 1,331000 |

| Alaska | 894,000 |

| California San Joaquin Valley |

515,000 |

| Oklahoma | 177,000 |

| New Mexico | 171,000 |

The San Joaquin Valley is also home to 21 giant oil fields that have produced over 100 million barrels of oil each, with four "super giants" that have produced over 1 billion barrels of oil. Among these "super giants" are Midway-Sunset, the largest oil field in the lower 49 United States, and Elk Hills, the former United States Naval Petroleum Reserve.

For a chronology of the state's oil industry see California oil and gas industry#Chronology of the California oil industry.

Natural gas

In 2020 the state was the 14th largest producer of natural gas in the United States, with a total annual production of over 170 billion cu feet of gas.[22] In 2014 natural gas was the second most widely used energy source in California. About 45% was burned in gas-fired plants for electricity generation; the proportion increases as coal-burning plants are phased out and nearly all new plants are powered by natural gas. One of the main advantages of natural gas is that it only produces about 55% as much CO2 as coal for the same amount of electricity produced. About 9% of the natural gas was used in facilitating the extraction of more oil and gas. Another 21% was used for residential space and water heating, cooking, clothes drying, etc.; 9% was used for commercial building and water heating, and 15% was used in industrial use.[23] California imports about 85% of its natural gas, using six large gas pipelines from Texas, New Mexico and Canada.

California businessmen

In 1911 a new California Assembly created a new railroad commission with vastly enlarged powers and brought public utilities under state supervision. Organized businessmen were the leaders of both of these reforms. The driving force for railroad regulation came less from an outraged public seeking lower rates than from shippers and merchants who wanted to stabilize their businesses. Public utility officers spearheaded campaigns for the passage, and later the enlargement of the Public Utilities Act. They expected that state regulation would reduce wasteful competition between their companies, improve the value of their companies' securities, and allow them to escape continual wrangling with county and municipal authorities.[24]

Although the businessmen were influential in obtaining the passage of bills they wanted, no group of businessmen dominated the California legislature or the railroad commission after 1910. Legislation proposed by some businessmen was opposed by other business interests.[24] Organized labor made significant gains during the Progressive Era, but they were not a result of benevolent, middle-class reformer actions, but of powerful lobbying activity on the part of unions with their solid base in San Francisco and Oakland.

In the 1920s, most progressives came to view the business culture of the day not as a repudiation of progressive goals but as the fulfillment of it. The most important progressive victories of 1921 were the passage of administrative reorganization laws, the King Bill, increasing corporate taxes, and a progressive budget. In 1927–31, governor Clement Calhoun Young (1869–1947) brought more progressivism to the state. The state began large-scale hydroelectric power development, and began state aid to the handicapped. California became the first state to enact a modern old-age pension law. The state park system was upgraded, and California (like most states) rapidly expanded its highway program, funding it through a tax on gasoline, and creating the California Highway Patrol.[25]

California women

California women had the right to own property in their own name since the first California Constitution in 1850. In 1911 California voters, in a special election, narrowly granted women the right to vote, nine years before the 19th Amendment enfranchised women nationally in 1920, but over 41 years later than the women of Wyoming had been granted the right to vote. Women's clubs flourished and turned a spotlight on issues such as public schools, dirt and pollution, and public health. California women were leaders in the temperance movement, moral reform, conservation, public schools, recreation, and other issues. They helped pass the 18th amendment, which established Prohibition in 1920. Initially, women did not often run for public office.[26]

Progressive Era

California played a major role in the Progressive Movement. It was the only state where the Progressives took control of the Republican Party.

Lincoln–Roosevelt League

California was a leader in the Progressive Movement from the 1890s into the 1920s. A coalition of reform-minded Republicans, especially in southern California, coalesced around Thomas Bard (1841–1915). Bard's election in 1899 as United States senator enabled the anti-machine Republicans to sustain a continuing opposition to the Southern Pacific Railroad's political power in California. They helped nominate George C. Pardee for governor in 1902 and formed the "Lincoln–Roosevelt League". In 1910 Hiram W. Johnson won the campaign for governor under the slogan "Kick the Southern Pacific out of politics." In 1912 Johnson became the running mate for Theodore Roosevelt on the new Bull Moose Party ticket.[27]

By 1916 the Progressives were supporting labor unions, which helped them in ethnic enclaves in the larger cities but alienated the native-stock Protestant, middle-class voters who voted heavily against Senator Johnson and President Wilson in 1916.[28]

Political progressivism varied across the state. Los Angeles (population 102,000 in 1900) focused on the dangers posed by the Southern Pacific Railroad, the liquor trade, and labor unions; San Francisco (population 342,000 in 1900) was confronted with a corrupt union-backed political "machine" that was finally overthrown following the earthquake of 1906. Smaller cities like San Jose (which had a population of 22,000 in 1900) had somewhat different concerns, such as fruit cooperatives, urban development, rival rural economies, and Asian labor.[29] San Diego (population 18,000 in 1900) had both the Southern Pacific and a corrupt machine.[30]

World War I

California played a major role in terms of agriculture, industry, finance and propaganda during World War I.[31] Its industrialized agriculture exported food to the Allies, 1914–1917, and expanded again when America entered the war in 1917. After the war ended, it shipped large quantities of food to central Europe as part of national relief efforts. Hollywood was thoroughly engaged, with feature films and training films.[32] Attractive climate conditions led to the addition of numerous Army and Navy training camps and airfields. Construction of transports and warships boosted the economy of the Bay area.

Organized labor

Organized labor was centered in San Francisco for much of the state's early history. By the opening decades of the twentieth century, labor efforts had expanded to Los Angeles, Long Beach and the Central Valley. In 1901, the San Francisco-based City Front Federation was reputed to be the strongest trade federation in the country. It grew out of intense organizational drives in every trade during the boom around the start of the 20th century.

Employers also organized during the building trades strike of 1900 and the (San Francisco) City Front Federation strike of 1901, which led to the founding of the Building Trades Council. The open shop question was at stake. Out of the City Front strike came the Union Labor Party, because workers were angry at the mayor for using the police to protect strikebreakers. Eugene Schmitz was elected mayor in 1902 on the party's ticket, making San Francisco the only town in the United States, for a time, to be run by labor. A combination of corruption and unscrupulous reformers culminated in graft prosecutions in 1907.

In 1910, Los Angeles was still an open shop, and employers in the north threatened for a new push to open San Francisco shops. Responding, labor sent delegations south in June 1910. National organizers were sent in during a lockout of 1,200 idled metal-trades workers. Then occurred an incident that would set back Los Angeles organizing for years: on October 10, 1910, a bomb exploded at the Los Angeles Times newspaper plant that killed 21 workers.

In 1912, the San Diego Common Council passed an ordinance to restrict free speech and public demonstrations over a diverse neighborhood where the local labor groups met. This columnated into the San Diego free speech fight, where police confrontations led to mass arrests, police brutality, and the lynching of dozens of people by patriotic vigilantes in reeducation camps that were overlooked by law enforcement.

In the decade following, the rapid growth of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW, or Wobblies) in un-unionized trades, logging, wheat farming, and lumber camps began extending its efforts to mines, ports and agriculture. The IWW came to public notice after the Wheatland Hop Riot, when a sheriff's posse broke up a protest meeting and four people died. It led to the first legislation protecting field labor. The IWW was harmed by anti-union drives and prosecution of members under the California Criminal Syndicalism Act.

The IWW was also involved in the 1923 seamen's strike at San Pedro, where Upton Sinclair was arrested for reciting the Declaration of Independence. The man who became the most prominent Wobbly of all, Thomas Mooney, soon became a cause-celebre of labor and the most important political prisoner in America.

Labor in the 1920s

The Preparedness Day Bombing killed ten people and hurt labor for decades. During the 1920s, the open shop efforts succeeded through a coordinated strategy called the "American Plan". In one case, the Industrial Association of San Francisco raised over a million dollars to break the building trades strikes in 1921 that led to the collapse of the building trades unions. This employers association cut wages twice in one year, and the Metal Trades Council was defeated, losing an agreement that had been in effect since 1907. The Seamen's Union also suffered defeat in 1921.

Labor in the 1930s

Labor unions

Unions grew rapidly after 1935 with political and legal support from the national New Deal and its Wagner Act of 1935. The most serious strike came in 1934 along the state's ports. In May 1934, dock workers and longshoremen along the West Coast went on strike for better hours and pay, a union hiring hall and a coast-wide contract. Communists were in control of the union, the International Longshoremen's Association (ILA), led by Harry Bridges (1901–1990).[33]

On "Bloody Thursday", July 5, 1934, San Francisco was swept by bloody rioting. Striking maritime workers, pitting themselves against police, took control of much of the waterfront and warehouse areas of the city. Two workers were killed and hundreds were clubbed and gassed. The West Coast Waterfront Strike lasted 83 days, with longshoremen returning to work on July 31. Arbitration was agreed to, and it resulted in a victory for the strikers and the unionization of all West Coast ports in the United States.[33]

San Francisco in the late 1930s had 120,000 union members. Longshoremen wore union buttons on their white union-made caps, Teamsters drove trucks as unionists, and fishermen, taxi drivers, streetcar conductors, motormen, newsboys, retail clerks, hotel employees, newspapermen and bootblacks all had representation. Against 30,000 trade union members in 1933–34, Los Angeles by the late thirties had 200,000, even against a severe 1938 anti-picketing ordinance. But Los Angeles became unionized in the mass production industries of aircraft, auto, rubber, and oil, and at the yards of San Pedro. Later, drives for unionization spread through musicians, teamsters, building trades, movies, actors, writers and directors.

Farm labor

Farm labor remained unorganized, the work brutal and underpaid. In the 1930s, 200,000 farm laborers traveled the state in tune with the seasons.[citation needed] Unions were accused of an "inland march" against landowners' rights when they took up the early effort to organize farm labor. A number of valley towns endorsed anti-picketing ordinances to thwart organizing.

In the 1933–1934 period, a wave of agricultural strikes flooded the Central Valley, including the Imperial Valley lettuce strike and San Joaquin Valley cotton strike. In the 1936 Salinas lettuce strike, vigilante violence shocked the nation. Again, in the spring of 1938, about three hundred men, women and children were driven by vigilantes from their homes in Grass Valley and Nevada City.

A 1938 ballot proposition against picketing, "Proposition #1", considered fascist by commentators for the state grange, became a huge political struggle. Proposition #1 failed at the polls. Soon, racist distinctions fell as California unions began to admit non-white members.

By the advent of World War II, California had an old-age assistance law, unemployment compensation, a 48-hour work week maximum for women, an apprentice law, and workplace safety rules.

Okies

"Okies" were the 250,000 hard-luck migrants who fled the Dust Bowl and depression in Oklahoma and neighboring states in the 1930s in search of a better future. Many sought farm labor jobs advertised in the Central Valley. They were harshly disparaged at the time. Police were stationed at the Arizona line to keep them out, and the state legislature passed a law to keep them out, but it was overturned by the United States Supreme Court.[34] Historian James Gregory has explored the long-term impact of the Okies on California society. Gregory finds that most came from urban backgrounds, and one in six had been a white-collar worker. He notes that in The Grapes of Wrath, novelist John Steinbeck saw the migrants becoming active agitators for unions and the New Deal, demanding higher wages and better housing conditions. Steinbeck did not foresee that most Okies would move into well-paid jobs in war industries in the 1940s. The children and grandchildren of the Okies seldom returned to Oklahoma. They did leave the farms and became concentrated in southern California's cities and suburbs. Long-term cultural impacts include a commitment to evangelical Protestantism (especially the Pentecostals and the Southern Baptists),[35] a love of country music,[36] populist conservatism of the sort that boosted Ronald Reagan, and strong support for traditional moral and cultural values.[37][38]

Radical politics

In the 1934 California gubernatorial election, novelist Upton Sinclair was the narrowly defeated Democratic nominee, running on the platform of the socialist End Poverty in California movement, a radical response to the Great Depression. Other radical movements flourished, such as the Townsend Plan for old age pension, and "Ham and Eggs", which promised "$30 Every Thursday" to everyone over age 50. Voters narrowly rejected it in 1938, and the utopians failed to enact any panaceas; however, the movements did spawn a generation of activists on the left.[39]

Water projects

The only way California can support its extensive population and agriculture is to store water in numerous reservoirs and use pipes, tunnels, pumps and canals to distribute it where it is needed when it is needed. Beginning before 1900, California has built extensive water projects costing many billions of dollars to store and move water where it is needed. California water comes primarily from snowfall in the Sierra Nevada in the northern part of the state during the relatively short winter from about October to March. The rest of the year typically has very little rainfall or snowfall. California weather is also prone to extended droughts that can last several years. During an average rainfall year, about 14% of the power used in California is generated by hydroelectricity.[40]

Los Angeles Aqueduct

The Los Angeles Aqueduct runs from the Owens Valley, through the Mojave Desert and its Antelope Valley, to dry Los Angeles far to the south. The aqueduct project began in 1905 when the people of Los Angeles approved a US$1.5 million bond for the "purchase of lands and water and the inauguration of work on the aqueduct".[41][42]

On June 12, 1907, a second bond was passed with a budget of US$24.5 million to fund the project.[41][43] Construction began in 1908 and finished in 1913 while employing 5,000 workers during that period.[44][45][46][47]

The Los Angeles aqueduct as originally constructed consisted of six storage reservoirs and 215 miles (346 km) of conduit. Beginning 3.5 miles (5.6 km) north of Black Rock Springs, the aqueduct diverts the Owens River into an unlined canal to begin its 233-mile (375 km) journey south to the Lower San Fernando Reservoir.[48] This reservoir was later renamed the Lower Van Norman Reservoir. Creeks flowing from the eastern Sierra are diverted into the aqueduct.

The original project consisted of 24 miles (39 km) of open unlined canal, 37 miles (60 km) of lined open canal, 97 miles (156 km) of covered concrete conduit, 43 miles (69 km) of concrete tunnels, and 12.05 miles (19.39 km) of steel siphons. To build it required 120 miles (190 km) of railroad track, two hydroelectric plants, three cement plants, 170 miles (270 km) of power lines, 240 miles (390 km) of telephone line, and 500 miles (800 km) of roads.[49] It was later expanded with the construction of the Mono Extension and the Second Los Angeles Aqueduct.[50]

The Los Angeles Aqueduct uses gravity alone to move water and to generate electricity, so it is cost-efficient to operate.[51] Finished in 1911, the Los Angeles Aqueduct was the brain-child of the self-taught engineer William Mulholland and is still in use today.

Hetch Hetchy

Hetch Hetchy is a valley that lies in the northwestern part of Yosemite National Park and is drained by the Tuolumne River. Starting in about 1901, San Francisco started looking for a new supply of municipal water. Following the disastrous 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire, this search intensified, and they finally chose the Tuolumne River as the "best" available water resource. The City and County of San Francisco bought most of the water rights to the Tuolumne River watershed in 1910. The Hetch Hetchy project centered on damming the main Tuolumne River as it meandered through Hetch Hetchy's wide glacial-cut valley. The river, with its source in a perpetual glacier on 13,000-foot (4,000 m) Mount Lyell, drains 650 square miles (1,700 km2) of watershed of the rugged granite mountains sloping west from the Sierra Nevada crest. The Hetch Hetchy water system's goal was providing up to 400,000,000 US gallons (1.5×109 L) of water per day to San Francisco and the growing Bay Region and tap the hydroelectric power that would be generated by a dam and power stations. After a vigorous debate, the United States Congress passed the Raker Act in 1913 which authorized the building of dam(s), hydroelectricity plant and municipal water supply system inside part of Yosemite National Park. The act was signed by President Woodrow Wilson in February 1916.

A key element of the plan was a new dam and reservoir in the Hetch Hetchy Valley, but access to the area was poor, so a railroad was planned to help build the dam. The steep terrain dictated a 4-degree roadbed, roughly twice as steep as a "regular" railroad. The steep grades dictated geared-down locomotives. The first 9 miles (14 km) of the Hetch Hetchy Railroad (HHRR) were completed in 1915, and the remaining 59 miles (95 km) were completed by October 1917. Construction costs for the HHRR were about US$3 million, far less than what the city might have paid contractors to transport workers, concrete and other materials for the dam over the rough and steep terrain by 12 mule train wagons.[citation needed] The president of the railroad was San Francisco Mayor James Rolph, and the vice president and general manager was the construction project's chief engineer Michael O'Shaughnessy. The Hetch Hetchy Railroad was begun as a connection of the Sierra Railway at Hetch Hetchy Junction, 15 miles (24 km) west of Jamestown, and extended another 68 miles (109 km) to the Hetch Hetchy Dam (later named the O'Shaughnessy Dam after the chief engineer) site for delivery of construction workers and materials. The regular trains were supplemented by trucks converted to run on the tracks to carry unscheduled loads of men or supplies or evacuate ambulance patients. The railroad was dismantled and part of its road bed converted into a highway after the Michael O'Shaughnessy dam was completed, and the new 2,030,000-acre-foot-capacity (2.50×109 m3) Don Pedro Reservoir built in 1971 flooded part of the original track line.[52]

The vast Hetch Hetchy Project undertaking created the 360,000 acre-feet (440,000,000 m3) Hetch Hetchy Reservoir, miles of tunnels, and a 150-mile (240 km) aqueduct to deliver the water and power lines to deliver electricity to the Bay Area. Of the many dams, reservoirs, and power plants, three were in the high country of Tuolumne County. The main dam was built in two phases. Large pipes called penstocks channeled water down the mountain to the main Moccasin Power hydroelectric plant completed in 1925 and rebuilt in 1968.

In 1923, the O'Shaughnessy Dam was completed to its initial height on the Tuolumne River, creating the Hetch Hetchy Reservoir. The dam was raised 65.5 feet (20.0 m) higher to its present 430 feet (130 m) height in 1939.[53] The dam and reservoir are the centerpiece of the Hetch Hetchy Project, which in 1934 began to deliver water 167 miles (269 km) west to San Francisco and its client municipalities in the greater San Francisco Bay Area.

Central Valley Project

Trinity Dam was the main storage feature of the Central Valley Project (CVP) proposal to divert water from the Trinity River in northwestern California to augment water supplies in the CVP service area. In 1948, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, which was responsible for the construction and operations of most CVP facilities, devised a plan of four dams and two tunnels to capture and store some of the flow of the Trinity River and transport it to the Sacramento River, generating a net surplus of hydroelectric power along the way. Trinity Dam was the main storage feature of the division, providing a stable flow to the Lewiston Dam, the diversion point for Trinity River waters into the Central Valley via the Trinity Tunnel.[54][55] Trinity Lake was completely filled with water from the Trinity River by 1963, becoming the third largest lake in California, with 145 miles (233 km) of shoreline.

Shasta Dam is a concrete arch-gravity dam[56] across the Sacramento River in the northern part of California, at the north end of the Sacramento Valley. The dam mainly serves long-term water storage and flood control in its 4,500,000-acre-foot (5.6×109 m3) reservoir, Shasta Lake. The lake has 365 miles (587 km) of mostly steep mountainous shoreline covered with tall evergreen trees and manzanita. The lake's maximum depth is 517 feet (158 m). Water released from the lake generates hydroelectric power. At 602 feet (183 m) high, the dam is the ninth-tallest dam in the United States and forms the largest reservoir in California.

Shasta Dam was envisioned as early as 1919 because of frequent floods and droughts troubling California's largest agricultural region, the Central Valley. Shasta Dam was first authorized in the 1930s as a state undertaking. However, this coincided with the Great Depression, and building of the dam was transferred to the federal Bureau of Reclamation as a public works project. Construction started in earnest in 1937 under the supervision of Chief Engineer Frank Crowe. During its building, the dam provided thousands of much-needed jobs; it was finished 26 months ahead of schedule in 1945. When completed, the dam was the second-tallest in the United States after Hoover, and was considered one of the greatest engineering feats of all time.

Even before its dedication, Shasta Dam served an important role in World War II, providing electricity to California factories, and it still plays a vital part in the management of state water resources. However, it has brought about major changes to the environment and ecology of the Sacramento River, and met with controversy over its significant destruction of Native American tribal lands. In recent years, there has been debate over whether or not to raise the dam in order to allow for increased water storage and hydropower generation.

Pardee Dam is a 345-foot-high (105 m) structure across the Mokelumne River on the boundary between Amador and Calaveras counties, in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada approximately 30 miles (48 km) northeast of Stockton. The Pardee Reservoir impounds 210,000 acre-feet (260,000,000 m3) of water when it is full.[57]

Construction on the Mokelumne Aqueduct and Pardee Dam began in 1926, and by 1929 the 345-foot-high (105 m) concrete arch Pardee Dam and the First Mokelumne Aqueduct, consisting of a single pipeline, were completed. The first deliveries to the Bay Area from the 210,000-acre-foot (260,000,000 m3) reservoir were made on June 23, 1929. At the time of completion, Pardee Dam was the tallest in the world (this record was surpassed one year later by Diablo Dam in Washington). In 1949, a second pipeline was built, and in 1963 the third pipeline was constructed, bringing the aqueduct to its present capacity.[58] In 1964, the second major dam and reservoir on the Mokelumne River, the Camanche Dam and 410,000-acre-foot (510,000,000 m3) Camanche Reservoir, were completed below Pardee. The Mokelumne Aqueduct and dam(s), run by the East Bay Municipal Utility District (EBMUD), is the primary water source for 35 communities in Alameda and Contra Costa counties, including Berkeley and Oakland. EBMUD holds water rights to almost all of the 30,000 acres (120 km2) in the Mokelumne River watershed and 25,000 acres (100 km2) in other watersheds. EBMUD also has an American River water right that could be sent to the Mokelumne Aqueduct through the Folsom South Canal.

The California Aqueduct is a system of canals, tunnels, and pipelines that conveys water collected from the Sierra Nevada mountains and valleys of northern and central California to southern California.[59] The Department of Water Resources (DWR) operates and maintains the California Aqueduct, including the two largest pumped-storage hydroelectric plants in California, Castaic and Gianelli. Gianelli is located at the base of San Luis Dam, which forms San Luis Reservoir, the largest off-stream reservoir in the United States. The Castaic Power Plant is located at the northern end of Castaic Lake, while Castaic Dam is located at the southern end.

The aqueduct begins at the Sacramento–San Joaquin River Delta at the Banks Pumping Plant, which pumps from the Clifton Court Forebay. Water is pumped by the Banks Pumping Plant to the Bethany Reservoir, which serves as a forebay for the South Bay Aqueduct via the South Bay Pumping Plant. From the Bethany Reservoir, the aqueduct flows by gravity approximately 60 miles (97 km) to the O'Neill Forebay at the San Luis Reservoir. From the O'Neill Forebay, it flows approximately 16 miles (26 km) to the Dos Amigos Pumping Plant. After Dos Amigos, the aqueduct flows about 95 miles (153 km) to where the Coastal Branch splits from the "main line". The split is approximately 16 miles (26 km) south-southeast of Kettleman City. After the Coastal Branch, the line continues by gravity another 66 miles (106 km) to the Buena Vista Pumping Plant. From the Buena Vista, it flows approximately 27 miles (43 km) to the Teerink Pumping Plant. After Teerink it flows about 2.5 miles (4.0 km) to the Chrisman Pumping Plant. Chrisman is the last pumping plant before the Edmonston Pumping Plant, which is 13 miles (21 km) from Chrisman. South of the plant the west branch splits off in a southwesterly direction to serve the Los Angeles Basin. At the Edmonston Pumping Plant it is pumped 1,926 feet (587 m) over the Tehachapi Mountains.[60]

Water flows through the aqueduct in a series of abrupt rises and gradual falls. The water flows down a long segment, built at a slight grade, and arrives at a pumping station powered by Path 66 or Path 15. The pumping station raises the water, where it again gradually flows downhill to the next station. However, where there are substantial drops, the water's potential energy is recaptured by hydroelectric plants. The initial pumping station fed by the Sacramento River Delta raises the water 240 ft (73 m), while a series of pumps culminating at the Edmonston Pumping Plant raises the water 1,926 ft (587 m) over the Tehachapi Mountains. The Edmonston Pumping station requires so much power that several power lines off Path 15 and Path 26 are needed to ensure proper operation of the pumps.

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=History_of_California_(1900–present)

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk