A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Part of a series on |

| Organized labour |

|---|

|

A trade union (British English) or labor union (American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers whose purpose is to maintain or improve the conditions of their employment,[1] such as attaining better wages and benefits, improving working conditions, improving safety standards, establishing complaint procedures, developing rules governing status of employees (rules governing promotions, just-cause conditions for termination) and protecting and increasing the bargaining power of workers.

Trade unions typically fund their head office and legal team functions through regularly imposed fees called union dues. The union representatives in the workforce are usually made up of workplace volunteers who are often appointed by members through internal democratic elections. The trade union, through an elected leadership and bargaining committee, bargains with the employer on behalf of its members, known as the rank and file, and negotiates labour contracts (collective bargaining agreements) with employers.

Unions may organize a particular section of skilled or unskilled workers (craft unionism),[2] a cross-section of workers from various trades (general unionism), or an attempt to organize all workers within a particular industry (industrial unionism). The agreements negotiated by a union are binding on the rank-and-file members and the employer, and in some cases on other non-member workers. Trade unions traditionally have a constitution which details the governance of their bargaining unit and also have governance at various levels of government depending on the industry that binds them legally to their negotiations and functioning.

Originating in the United Kingdom, trade unions became popular in many countries during the Industrial Revolution. Trade unions may be composed of individual workers, professionals, past workers, students, apprentices or the unemployed. Trade union density, or the percentage of workers belonging to a trade union, is highest in the Nordic countries.[3][4]

Definition

Since the publication of the History of Trade Unionism (1894) by Sidney and Beatrice Webb, the predominant historical view is that a trade union "is a continuous association of wage earners for the purpose of maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment".[1] Karl Marx described trade unions thus: "The value of labour-power constitutes the conscious and explicit foundation of the trade unions, whose importance for the ... working class can scarcely be overestimated. The trade unions aim at nothing less than to prevent the reduction of wages below the level that is traditionally maintained in the various branches of industry. That is to say, they wish to prevent the price of labour-power from falling below its value" (Capital V1, 1867, p. 1069). Early socialists also saw trade unions as a way to democratize the workplace, in order to obtain political power.[5]

A modern definition by the Australian Bureau of Statistics states that a trade union is "an organisation consisting predominantly of employees, the principal activities of which include the negotiation of rates of pay and conditions of employment for its members".[6]

Recent historical research by Bob James puts forward the view that trade unions are part of a broader movement of benefit societies, which includes medieval guilds, Freemasons, Oddfellows, friendly societies, and other fraternal organizations.[7]

History

Trade guilds

Following the unification of the city-states in Assyria and Sumer by Sargon of Akkad into a single empire c. 2334 BC, common Mesopotamian standards for length, area, volume, weight, and time used by artisan guilds in each city was promulgated by Naram-Sin of Akkad (c. 2254–2218 BC), Sargon's grandson, including for shekels.[8] Codex Hammurabi Law 234 (c. 1755–1750 BC) stipulated a 2-shekel prevailing wage for each 60-gur (300-bushel) vessel constructed in an employment contract between a shipbuilder and a ship-owner.[9][10][11] Law 275 stipulated a ferry rate of 3-gerah per day on a charterparty between a ship charterer and a shipmaster. Law 276 stipulated a 21⁄2-gerah per day freight rate on a contract of affreightment between a charterer and shipmaster, while Law 277 stipulated a 1⁄6-shekel per day freight rate for a 60-gur vessel.[12][13][11] In 1816, an archaeological excavation in Minya, Egypt (under an Eyalet of the Ottoman Empire) produced a Nerva–Antonine dynasty-era tablet from the ruins of the Temple of Antinous in Antinoöpolis, that prescribed the rules and membership dues of a burial society collegium established in Lanuvium, in approximately 133 AD during the reign of Hadrian (117–138) of the Roman Empire.[14]

A collegium was any association in ancient Rome that acted as a legal entity. Following the passage of the Lex Julia during the reign of Julius Caesar (49–44 BC), and their reaffirmation during the reign of Caesar Augustus (27 BC–14 AD), collegia required the approval of the Roman Senate or the Roman emperor in order to be authorized as legal bodies.[15] Ruins at Lambaesis date the formation of burial societies among Roman Army soldiers and Roman Navy mariners to the reign of Septimius Severus (193–211) in 198 AD.[16] In September 2011, archaeological investigations done at the site of the artificial harbor Portus in Rome revealed inscriptions in a shipyard constructed during the reign of Trajan (98–117) indicating the existence of a shipbuilders guild.[17] Rome's La Ostia port was home to a guildhall for a corpus naviculariorum, a collegium of merchant mariners.[18] Collegium also included fraternities of Roman priests overseeing ritual sacrifices, practising augury, keeping scriptures, arranging festivals, and maintaining specific religious cults.[19]

Modern trade unions

While a commonly held mistaken view holds modern trade unionism to be a product of Marxism, the earliest modern trade unions predate Marx's Communist Manifesto (1848) by almost a century (and Marx's writings themselves frequently address the prior existence of the workers' movements of his time.) The first recorded labour strike in the United States was by Philadelphia printers in 1786, who opposed a wage reduction and demanded $6 per week in wages.[20][21] The origins of modern trade unions can be traced back to 18th-century Britain, where the Industrial Revolution drew masses of people, including dependents, peasants and immigrants, into cities. Britain had ended the practice of serfdom in 1574, but the vast majority of people remained as tenant-farmers on estates owned by the landed aristocracy. This transition was not merely one of relocation from rural to urban environs; rather, the nature of industrial work created a new class of "worker". A farmer worked the land, raised animals and grew crops, and either owned the land or paid rent, but ultimately sold a product and had control over his life and work. As industrial workers, however, the workers sold their work as labour and took directions from employers, giving up part of their freedom and self-agency in the service of a master. The critics of the new arrangement would call this "wage slavery",[22] but the term that persisted was a new form of human relations: employment. Unlike farmers, workers often had less control over their jobs; without job security or a promise of an on-going relationship with their employers, they lacked some control over the work they performed or how it impacted their health and life. It is in this context that modern trade unions emerge.

In the cities, trade unions encountered much hostility from employers and government groups. In the United States, unions and unionists were regularly prosecuted under various restraint of trade and conspiracy laws, such as the Sherman Antitrust Act.[23][24] This pool of unskilled and semi-skilled labour spontaneously organized in fits and starts throughout its beginnings,[1] and would later be an important arena for the development of trade unions. Trade unions have sometimes been seen as successors to the guilds of medieval Europe, though the relationship between the two is disputed, as the masters of the guilds employed workers (apprentices and journeymen) who were not allowed to organize.[25][26]

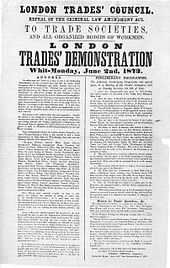

Trade unions and collective bargaining were outlawed from no later than the middle of the 14th century, when the Ordinance of Labourers was enacted in the Kingdom of England, but their way of thinking was the one that endured down the centuries, inspiring evolutions and advances in thinking which eventually gave workers more power. As collective bargaining and early worker unions grew with the onset of the Industrial Revolution, the government began to clamp down on what it saw as the danger of popular unrest at the time of the Napoleonic Wars. In 1799, the Combination Act was passed, which banned trade unions and collective bargaining by British workers. Although the unions were subject to often severe repression until 1824, they were already widespread in cities such as London. Workplace militancy had also manifested itself as Luddism and had been prominent in struggles such as the 1820 Rising in Scotland, in which 60,000 workers went on a general strike, which was soon crushed. Sympathy for the plight of the workers brought repeal of the acts in 1824, although the Combination Act 1825 severely restricted their activity.[citation needed]

By the 1810s, the first labour organizations to bring together workers of divergent occupations were formed. Possibly the first such union was the General Union of Trades, also known as the Philanthropic Society, founded in 1818 in Manchester. The latter name was to hide the organization's real purpose in a time when trade unions were still illegal.[27]

National general unions

The first attempts at forming a national general union in the United Kingdom were made in the 1820s and 30s. The National Association for the Protection of Labour was established in 1830 by John Doherty, after an apparently unsuccessful attempt to create a similar national presence with the National Union of Cotton-spinners. The Association quickly enrolled approximately 150 unions, consisting mostly of textile related unions, but also including mechanics, blacksmiths, and various others. Membership rose to between 10,000 and 20,000 individuals spread across the five counties of Lancashire, Cheshire, Derbyshire, Nottinghamshire and Leicestershire within a year.[28] To establish awareness and legitimacy, the union started the weekly Voice of the People publication, having the declared intention "to unite the productive classes of the community in one common bond of union."[29]

In 1834, the Welsh socialist Robert Owen established the Grand National Consolidated Trades Union. The organization attracted a range of socialists from Owenites to revolutionaries and played a part in the protests after the Tolpuddle Martyrs' case, but soon collapsed.

More permanent trade unions were established from the 1850s, better resourced but often less radical. The London Trades Council was founded in 1860, and the Sheffield Outrages spurred the establishment of the Trades Union Congress in 1868, the first long-lived national trade union center. By this time, the existence and the demands of the trade unions were becoming accepted by liberal middle-class opinion. In Principles of Political Economy (1871) John Stuart Mill wrote:

If it were possible for the working classes, by combining among themselves, to raise or keep up the general rate of wages, it needs hardly be said that this would be a thing not to be punished, but to be welcomed and rejoiced at. Unfortunately the effect is quite beyond attainment by such means. The multitudes who compose the working class are too numerous and too widely scattered to combine at all, much more to combine effectually. If they could do so, they might doubtless succeed in diminishing the hours of labour, and obtaining the same wages for less work. They would also have a limited power of obtaining, by combination, an increase of general wages at the expense of profits.[30]

Beyond this claim, Mill also argued that, because individual workers had no basis for assessing the wages for a particular task, labour unions would lead to greater efficiency of the market system.[31]

Legalization, expansion and recognition

British trade unions were finally legalized in 1872, after a Royal Commission on Trade Unions in 1867 agreed that the establishment of the organizations was to the advantage of both employers and employees.

This period also saw the growth of trade unions in other industrializing countries, especially the United States, Germany and France.

In the United States, the first effective nationwide labour organization was the Knights of Labor, in 1869, which began to grow after 1880. Legalization occurred slowly as a result of a series of court decisions.[32] The Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions began in 1881 as a federation of different unions that did not directly enrol workers. In 1886, it became known as the American Federation of Labor or AFL.

In Germany, the Free Association of German Trade Unions was formed in 1897 after the conservative Anti-Socialist Laws of Chancellor Otto von Bismarck were repealed.

In France, labour organization was illegal until 1884. The Bourse du Travail was founded in 1887 and merged with the Fédération nationale des syndicats (National Federation of Trade Unions) in 1895 to form the General Confederation of Labour.

In a number of countries during the 20th century, including in Canada, the United States and the United Kingdom, legislation was passed to provide for the voluntary or statutory recognition of a union by an employer.[33][34][35]

Prevalence worldwide

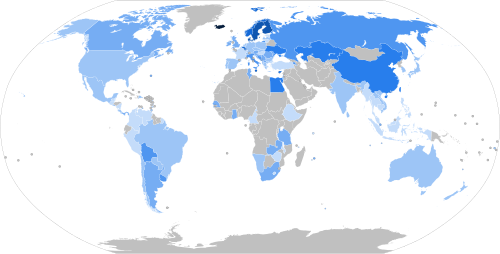

Union density has been steadily declining from the OECD average of 35.9% in 1998 to 27.9% in the year 2018.[3] The main reasons for these developments are a decline in manufacturing, increased globalization, and governmental policies.

The decline in manufacturing is the most direct influence, as unions were historically beneficial and prevalent in the sector; for this reason, there may be an increase in developing nations as OECD nations continue to export manufacturing industries to these markets. The second reason is globalization, which makes it harder for unions to maintain standards across countries. The last reason is governmental policies. These come from both sides of the political spectrum. In the UK and US, it has been mostly right-wing proposals that make it harder for unions to form or that limit their power. On the other side, there are many social policies such as minimum wage, paid vacation, parental leave, etc., that decrease the need to be in a union.[36]

The prevalence of labour unions can be measured by "union density", which is expressed as a percentage of the total number of workers in a given location who are trade union members.[37] The table below shows the percentage across OECD members.[3]

| Country | 2018 | 2017 | 2016 | 2015 | 2000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | 13.7 | 14.7 | .. | .. | 24.9 |

| Austria | 26.3 | 26.7 | 26.9 | 27.4 | 36.9 |

| Belgium | 50.3 | 51.9 | 52.8 | 54.2 | 56.6 |

| Canada | 25.9 | 26.3 | 26.3 | 29.4 | 28.2 |

| Chile | 16.6 | 17.0 | 17.7 | 16.1 | 11.2 |

| Czech Republic | 11.5 | 11.7 | 12.0 | 12.0 | 27.2 |

| Denmark | 66.5 | 66.1 | 65.5 | 67.1 | 74.5 |

| Estonia | 4.3 | 4.3 | 4.4 | 4.7 | 14.0 |

| Finland | 60.3 | 62.2 | 64.9 | 66.4 | 74.2 |

| France | 8.8 | 8.9 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 10.8 |

| Germany | 16.5 | 16.7 | 17.0 | 17.6 | 24.6 |

| Greece | .. | .. | 19.0 | .. | .. |

| Hungary | 7.9 | 8.1 | 8.5 | 9.4 | 23.8 |

| Iceland | 91.8 | 91.0 | 89.8 | 90.0 | 89.1 |

| Ireland | 24.1 | 24.3 | 23.4 | 25.4 | 35.9 |

| Israel | .. | 25.0 | .. | .. | 37.7 |

| Italy | 34.4 | 34.3 | 34.4 | 35.7 | 34.8 |

| Japan | 17.0 | 17.1 | 17.3 | 17.4 | 21.5 |

| Korea | .. | 10.5 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 11.4 |

| Latvia | 11.9 | 12.2 | 12.3 | 12.6 | .. |

| Lithuania | 7.1 | 7.7 | 7.7 | 7.9 | .. |

| Luxembourg | 31.8 | 32.1 | 32.3 | 33.3 | .. |

| Mexico | 12.0 | 12.5 | 12.7 | 13.1 | 16.7 |

| Netherlands | 16.4 | 16.8 | 17.3 | 17.7 | 22.3 |

| New Zealand | .. | 17.3 | 17.7 | 17.9 | 22.4 |

| Norway | 49.2 | 49.3 | 49.3 | 49.3 | 53.6 |

| Poland | .. | .. | 12.7 | .. | 23.5 |

| Portugal | .. | .. | 15.3 | 16.1 | .. |

| Slovak Republic | .. | .. | 10.7 | 11.7 | 34.2 |

| Slovenia | .. | .. | 20.4 | 20.9 | 44.2 |

| Spain | 13.6 | 14.2 | 14.8 | 15.2 | 17.5 |

| Sweden | 65.5 | 65.6 | 66.9 | 67.8 | 81.0 |

| Switzerland | 14.4 | 14.9 | 15.3 | 15.7 | 20.7 |

| Turkey | 9.2 | 8.6 | 8.2 | 8.0 | 12.5 |

| United Kingdom | 23.4 | 23.2 | 23.7 | 24.2 | 29.8 |

| United States | 10.1 | 10.3 | 10.3 | 10.6 | 12.9 |

Structure and politics

Unions may organize a particular section of skilled workers (craft unionism, traditionally found in Australia, Canada, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, the UK and the US[2]), a cross-section of workers from various trades (general unionism, traditionally found in Australia, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Netherlands, the UK and the US), or attempt to organize all workers within a particular industry (industrial unionism, found in Australia, Canada, Germany, Finland, Norway, South Korea, Sweden, Switzerland, the UK and the US).[citation needed] These unions are often divided into "locals", and united in national federations. These federations themselves will affiliate with Internationals, such as the International Trade Union Confederation. However, in Japan, union organisation is slightly different due to the presence of enterprise unions, i.e. unions that are specific to a plant or company. These enterprise unions, however, join industry-wide federations which in turn are members of Rengo, the Japanese national trade union confederation.

In Western Europe, professional associations often carry out the functions of a trade union. In these cases, they may be negotiating for white-collar or professional workers, such as physicians, engineers or teachers. In Sweden the white-collar unions have a strong position in collective bargaining where they cooperate with blue-colar unions in setting the "mark" (the industry norm) in negotiations with the employers' association in manufacturing industry.[38][39]

A union may acquire the status of a "juristic person" (an artificial legal entity), with a mandate to negotiate with employers for the workers it represents. In such cases, unions have certain legal rights, most importantly the right to engage in collective bargaining with the employer (or employers) over wages, working hours, and other terms and conditions of employment. The inability of the parties to reach an agreement may lead to industrial action, culminating in either strike action or management lockout, or binding arbitration. In extreme cases, violent or illegal activities may develop around these events.

In some regions, unions may face active repression, either by governments or by extralegal organizations, with many cases of violence, some having lead to deaths, having been recorded historically.[41]

Unions may also engage in broader political or social struggle. Social Unionism encompasses many unions that use their organizational strength to advocate for social policies and legislation favourable to their members or to workers in general. As well, unions in some countries are closely aligned with political parties. Many Labour parties were founded as the electoral arms of trade unions.

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Labor_union

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk