A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chlorine | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˈklɔːriːn, -aɪn/ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Appearance | pale yellow-green gas | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight Ar°(Cl) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chlorine in the periodic table | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number (Z) | 17 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group | group 17 (halogens) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Block | p-block | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [Ne] 3s2 3p5 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrons per shell | 2, 8, 7 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | gas | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | (Cl2) 171.6 K (−101.5 °C, −150.7 °F) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | (Cl2) 239.11 K (−34.04 °C, −29.27 °F) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (at STP) | 3.2 g/L | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| when liquid (at b.p.) | 1.5625 g/cm3[3] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Triple point | 172.22 K, 1.392 kPa[4] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Critical point | 416.9 K, 7.991 MPa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | (Cl2) 6.406 kJ/mol | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporisation | (Cl2) 20.41 kJ/mol | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | (Cl2) 33.949 J/(mol·K) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vapour pressure

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | −1, 0, +1, +2, +3, +4, +5, +6, +7 (a strongly acidic oxide) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 3.16 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionisation energies |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 102±4 pm | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Van der Waals radius | 175 pm | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | primordial | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

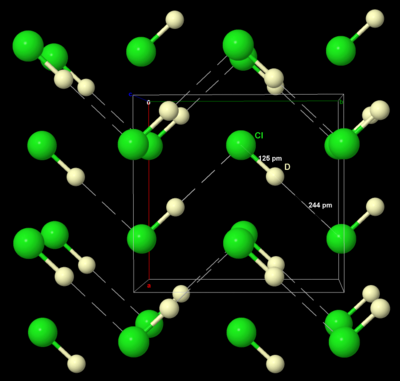

| Crystal structure | orthorhombic (oS8) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lattice constants | a = 630.80 pm b = 455.83 pm c = 815.49 pm (at triple point)[5] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | 8.9×10−3 W/(m⋅K) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrical resistivity | >10 Ω⋅m (at 20 °C) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | diamagnetic[6] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar magnetic susceptibility | −40.5×10−6 cm3/mol[7] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Speed of sound | 206 m/s (gas, at 0 °C) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | Cl2: 7782-50-5 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery and first isolation | Carl Wilhelm Scheele (1774) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Recognized as an element by | Humphry Davy (1808) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Isotopes of chlorine | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Chlorine is a chemical element; it has symbol Cl and atomic number 17. The second-lightest of the halogens, it appears between fluorine and bromine in the periodic table and its properties are mostly intermediate between them. Chlorine is a yellow-green gas at room temperature. It is an extremely reactive element and a strong oxidising agent: among the elements, it has the highest electron affinity and the third-highest electronegativity on the revised Pauling scale, behind only oxygen and fluorine.

Chlorine played an important role in the experiments conducted by medieval alchemists, which commonly involved the heating of chloride salts like ammonium chloride (sal ammoniac) and sodium chloride (common salt), producing various chemical substances containing chlorine such as hydrogen chloride, mercury(II) chloride (corrosive sublimate), and aqua regia. However, the nature of free chlorine gas as a separate substance was only recognised around 1630 by Jan Baptist van Helmont. Carl Wilhelm Scheele wrote a description of chlorine gas in 1774, supposing it to be an oxide of a new element. In 1809, chemists suggested that the gas might be a pure element, and this was confirmed by Sir Humphry Davy in 1810, who named it after the Ancient Greek χλωρός (khlōrós, "pale green") because of its colour.

Because of its great reactivity, all chlorine in the Earth's crust is in the form of ionic chloride compounds, which includes table salt. It is the second-most abundant halogen (after fluorine) and twenty-first most abundant chemical element in Earth's crust. These crustal deposits are nevertheless dwarfed by the huge reserves of chloride in seawater.

Elemental chlorine is commercially produced from brine by electrolysis, predominantly in the chloralkali process. The high oxidising potential of elemental chlorine led to the development of commercial bleaches and disinfectants, and a reagent for many processes in the chemical industry. Chlorine is used in the manufacture of a wide range of consumer products, about two-thirds of them organic chemicals such as polyvinyl chloride (PVC), many intermediates for the production of plastics, and other end products which do not contain the element. As a common disinfectant, elemental chlorine and chlorine-generating compounds are used more directly in swimming pools to keep them sanitary. Elemental chlorine at high concentration is extremely dangerous, and poisonous to most living organisms. As a chemical warfare agent, chlorine was first used in World War I as a poison gas weapon.

In the form of chloride ions, chlorine is necessary to all known species of life. Other types of chlorine compounds are rare in living organisms, and artificially produced chlorinated organics range from inert to toxic. In the upper atmosphere, chlorine-containing organic molecules such as chlorofluorocarbons have been implicated in ozone depletion. Small quantities of elemental chlorine are generated by oxidation of chloride ions in neutrophils as part of an immune system response against bacteria.

History

The most common compound of chlorine, sodium chloride, has been known since ancient times; archaeologists have found evidence that rock salt was used as early as 3000 BC and brine as early as 6000 BC.[9]

Early discoveries

Around 900, the authors of the Arabic writings attributed to Jabir ibn Hayyan (Latin: Geber) and the Persian physician and alchemist Abu Bakr al-Razi (c. 865–925, Latin: Rhazes) were experimenting with sal ammoniac (ammonium chloride), which when it was distilled together with vitriol (hydrated sulfates of various metals) produced hydrogen chloride.[10] However, it appears that in these early experiments with chloride salts, the gaseous products were discarded, and hydrogen chloride may have been produced many times before it was discovered that it can be put to chemical use.[11] One of the first such uses was the synthesis of mercury(II) chloride (corrosive sublimate), whose production from the heating of mercury either with alum and ammonium chloride or with vitriol and sodium chloride was first described in the De aluminibus et salibus ("On Alums and Salts", an eleventh- or twelfth century Arabic text falsely attributed to Abu Bakr al-Razi and translated into Latin in the second half of the twelfth century by Gerard of Cremona, 1144–1187).[12] Another important development was the discovery by pseudo-Geber (in the De inventione veritatis, "On the Discovery of Truth", after c. 1300) that by adding ammonium chloride to nitric acid, a strong solvent capable of dissolving gold (i.e., aqua regia) could be produced.[13] Although aqua regia is an unstable mixture that continually gives off fumes containing free chlorine gas, this chlorine gas appears to have been ignored until c. 1630, when its nature as a separate gaseous substance was recognised by the Brabantian chemist and physician Jan Baptist van Helmont.[14][en 1]

Isolation

The element was first studied in detail in 1774 by Swedish chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele, and he is credited with the discovery.[15][16] Scheele produced chlorine by reacting MnO2 (as the mineral pyrolusite) with HCl:[14]

- 4 HCl + MnO2 → MnCl2 + 2 H2O + Cl2

Scheele observed several of the properties of chlorine: the bleaching effect on litmus, the deadly effect on insects, the yellow-green colour, and the smell similar to aqua regia.[17] He called it "dephlogisticated muriatic acid air" since it is a gas (then called "airs") and it came from hydrochloric acid (then known as "muriatic acid").[16] He failed to establish chlorine as an element.[16]

Common chemical theory at that time held that an acid is a compound that contains oxygen (remnants of this survive in the German and Dutch names of oxygen: sauerstoff or zuurstof, both translating into English as acid substance), so a number of chemists, including Claude Berthollet, suggested that Scheele's dephlogisticated muriatic acid air must be a combination of oxygen and the yet undiscovered element, muriaticum.[18][19]

In 1809, Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac and Louis-Jacques Thénard tried to decompose dephlogisticated muriatic acid air by reacting it with charcoal to release the free element muriaticum (and carbon dioxide).[16] They did not succeed and published a report in which they considered the possibility that dephlogisticated muriatic acid air is an element, but were not convinced.[20]

In 1810, Sir Humphry Davy tried the same experiment again, and concluded that the substance was an element, and not a compound.[16] He announced his results to the Royal Society on 15 November that year.[14] At that time, he named this new element "chlorine", from the Greek word χλωρος (chlōros, "green-yellow"), in reference to its colour.[21] The name "halogen", meaning "salt producer", was originally used for chlorine in 1811 by Johann Salomo Christoph Schweigger.[22] This term was later used as a generic term to describe all the elements in the chlorine family (fluorine, bromine, iodine), after a suggestion by Jöns Jakob Berzelius in 1826.[23][24] In 1823, Michael Faraday liquefied chlorine for the first time,[25][26][27] and demonstrated that what was then known as "solid chlorine" had a structure of chlorine hydrate (Cl2·H2O).[14]

Later uses

Chlorine gas was first used by French chemist Claude Berthollet to bleach textiles in 1785.[28][29] Modern bleaches resulted from further work by Berthollet, who first produced sodium hypochlorite in 1789 in his laboratory in the town of Javel (now part of Paris, France), by passing chlorine gas through a solution of sodium carbonate. The resulting liquid, known as "Eau de Javel" ("Javel water"), was a weak solution of sodium hypochlorite. This process was not very efficient, and alternative production methods were sought. Scottish chemist and industrialist Charles Tennant first produced a solution of calcium hypochlorite ("chlorinated lime"), then solid calcium hypochlorite (bleaching powder).[28] These compounds produced low levels of elemental chlorine and could be more efficiently transported than sodium hypochlorite, which remained as dilute solutions because when purified to eliminate water, it became a dangerously powerful and unstable oxidizer. Near the end of the nineteenth century, E. S. Smith patented a method of sodium hypochlorite production involving electrolysis of brine to produce sodium hydroxide and chlorine gas, which then mixed to form sodium hypochlorite.[30] This is known as the chloralkali process, first introduced on an industrial scale in 1892, and now the source of most elemental chlorine and sodium hydroxide.[31] In 1884 Chemischen Fabrik Griesheim of Germany developed another chloralkali process which entered commercial production in 1888.[32]

Elemental chlorine solutions dissolved in chemically basic water (sodium and calcium hypochlorite) were first used as anti-putrefaction agents and disinfectants in the 1820s, in France, long before the establishment of the germ theory of disease. This practice was pioneered by Antoine-Germain Labarraque, who adapted Berthollet's "Javel water" bleach and other chlorine preparations.[33] Elemental chlorine has since served a continuous function in topical antisepsis (wound irrigation solutions and the like) and public sanitation, particularly in swimming and drinking water.[17]

Chlorine gas was first used as a weapon on April 22, 1915, at the Second Battle of Ypres by the German Army.[34][35] The effect on the allies was devastating because the existing gas masks were difficult to deploy and had not been broadly distributed.[36][37]

Properties

Chlorine is the second halogen, being a nonmetal in group 17 of the periodic table. Its properties are thus similar to fluorine, bromine, and iodine, and are largely intermediate between those of the first two. Chlorine has the electron configuration 3s23p5, with the seven electrons in the third and outermost shell acting as its valence electrons. Like all halogens, it is thus one electron short of a full octet, and is hence a strong oxidising agent, reacting with many elements in order to complete its outer shell.[38] Corresponding to periodic trends, it is intermediate in electronegativity between fluorine and bromine (F: 3.98, Cl: 3.16, Br: 2.96, I: 2.66), and is less reactive than fluorine and more reactive than bromine. It is also a weaker oxidising agent than fluorine, but a stronger one than bromine. Conversely, the chloride ion is a weaker reducing agent than bromide, but a stronger one than fluoride.[38] It is intermediate in atomic radius between fluorine and bromine, and this leads to many of its atomic properties similarly continuing the trend from iodine to bromine upward, such as first ionisation energy, electron affinity, enthalpy of dissociation of the X2 molecule (X = Cl, Br, I), ionic radius, and X–X bond length. (Fluorine is anomalous due to its small size.)[38]

All four stable halogens experience intermolecular van der Waals forces of attraction, and their strength increases together with the number of electrons among all homonuclear diatomic halogen molecules. Thus, the melting and boiling points of chlorine are intermediate between those of fluorine and bromine: chlorine melts at −101.0 °C and boils at −34.0 °C. As a result of the increasing molecular weight of the halogens down the group, the density and heats of fusion and vaporisation of chlorine are again intermediate between those of bromine and fluorine, although all their heats of vaporisation are fairly low (leading to high volatility) thanks to their diatomic molecular structure.[38] The halogens darken in colour as the group is descended: thus, while fluorine is a pale yellow gas, chlorine is distinctly yellow-green. This trend occurs because the wavelengths of visible light absorbed by the halogens increase down the group.[38] Specifically, the colour of a halogen, such as chlorine, results from the electron transition between the highest occupied antibonding πg molecular orbital and the lowest vacant antibonding σu molecular orbital.[39] The colour fades at low temperatures, so that solid chlorine at −195 °C is almost colourless.[38]

Like solid bromine and iodine, solid chlorine crystallises in the orthorhombic crystal system, in a layered lattice of Cl2 molecules. The Cl–Cl distance is 198 pm (close to the gaseous Cl–Cl distance of 199 pm) and the Cl···Cl distance between molecules is 332 pm within a layer and 382 pm between layers (compare the van der Waals radius of chlorine, 180 pm). This structure means that chlorine is a very poor conductor of electricity, and indeed its conductivity is so low as to be practically unmeasurable.[38]

Isotopes

Chlorine has two stable isotopes, 35Cl and 37Cl. These are its only two natural isotopes occurring in quantity, with 35Cl making up 76% of natural chlorine and 37Cl making up the remaining 24%. Both are synthesised in stars in the oxygen-burning and silicon-burning processes.[40] Both have nuclear spin 3/2+ and thus may be used for nuclear magnetic resonance, although the spin magnitude being greater than 1/2 results in non-spherical nuclear charge distribution and thus resonance broadening as a result of a nonzero nuclear quadrupole moment and resultant quadrupolar relaxation. The other chlorine isotopes are all radioactive, with half-lives too short to occur in nature primordially. Of these, the most commonly used in the laboratory are 36Cl (t1/2 = 3.0×105 y) and 38Cl (t1/2 = 37.2 min), which may be produced from the neutron activation of natural chlorine.[38]

The most stable chlorine radioisotope is 36Cl. The primary decay mode of isotopes lighter than 35Cl is electron capture to isotopes of sulfur; that of isotopes heavier than 37Cl is beta decay to isotopes of argon; and 36Cl may decay by either mode to stable 36S or 36Ar.[41] 36Cl occurs in trace quantities in nature as a cosmogenic nuclide in a ratio of about (7–10) × 10−13 to 1 with stable chlorine isotopes: it is produced in the atmosphere by spallation of 36Ar by interactions with cosmic ray protons. In the top meter of the lithosphere, 36Cl is generated primarily by thermal neutron activation of 35Cl and spallation of 39K and 40Ca. In the subsurface environment, muon capture by 40Ca becomes more important as a way to generate 36Cl.[42][43]

Chemistry and compounds

| X | XX | HX | BX3 | AlX3 | CX4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | 159 | 574 | 645 | 582 | 456 |

| Cl | 243 | 428 | 444 | 427 | 327 |

| Br | 193 | 363 | 368 | 360 | 272 |

| I | 151 | 294 | 272 | 285 | 239 |

Chlorine is intermediate in reactivity between fluorine and bromine, and is one of the most reactive elements. Chlorine is a weaker oxidising agent than fluorine but a stronger one than bromine or iodine. This can be seen from the standard electrode potentials of the X2/X− couples (F, +2.866 V; Cl, +1.395 V; Br, +1.087 V; I, +0.615 V; At, approximately +0.3 V). However, this trend is not shown in the bond energies because fluorine is singular due to its small size, low polarisability, and inability to show hypervalence. As another difference, chlorine has a significant chemistry in positive oxidation states while fluorine does not. Chlorination often leads to higher oxidation states than bromination or iodination but lower oxidation states than fluorination. Chlorine tends to react with compounds including M–M, M–H, or M–C bonds to form M–Cl bonds.[39]

Given that E°(1/2O2/H2O) = +1.229 V, which is less than +1.395 V, it would be expected that chlorine should be able to oxidise water to oxygen and hydrochloric acid. However, the kinetics of this reaction are unfavorable, and there is also a bubble overpotential effect to consider, so that electrolysis of aqueous chloride solutions evolves chlorine gas and not oxygen gas, a fact that is very useful for the industrial production of chlorine.[44]

Hydrogen chloride

The simplest chlorine compound is hydrogen chloride, HCl, a major chemical in industry as well as in the laboratory, both as a gas and dissolved in water as hydrochloric acid. It is often produced by burning hydrogen gas in chlorine gas, or as a byproduct of chlorinating hydrocarbons. Another approach is to treat sodium chloride with concentrated sulfuric acid to produce hydrochloric acid, also known as the "salt-cake" process:[45]

- NaCl + H2SO4 NaHSO4 + HCl

- NaCl + NaHSO4 Na2SO4 + HCl

In the laboratory, hydrogen chloride gas may be made by drying the acid with concentrated sulfuric acid. Deuterium chloride, DCl, may be produced by reacting benzoyl chloride with heavy water (D2O).[45]

At room temperature, hydrogen chloride is a colourless gas, like all the hydrogen halides apart from hydrogen fluoride, since hydrogen cannot form strong hydrogen bonds to the larger electronegative chlorine atom; however, weak hydrogen bonding is present in solid crystalline hydrogen chloride at low temperatures, similar to the hydrogen fluoride structure, before disorder begins to prevail as the temperature is raised.[45] Hydrochloric acid is a strong acid (pKa = −7) because the hydrogen bonds to chlorine are too weak to inhibit dissociation. The HCl/H2O system has many hydrates HCl·nH2O for n = 1, 2, 3, 4, and 6. Beyond a 1:1 mixture of HCl and H2O, the system separates completely into two separate liquid phases. Hydrochloric acid forms an azeotrope with boiling point 108.58 °C at 20.22 g HCl per 100 g solution; thus hydrochloric acid cannot be concentrated beyond this point by distillation.[46]

Unlike hydrogen fluoride, anhydrous liquid hydrogen chloride is difficult to work with as a solvent, because its boiling point is low, it has a small liquid range, its dielectric constant is low and it does not dissociate appreciably into H2Cl+ and HCl−

2 ions – the latter, in any case, are much less stable than the bifluoride ions (HF−

2) due to the very weak hydrogen bonding between hydrogen and chlorine, though its salts with very large and weakly polarising cations such as Cs+ and NR+

4 (R = Me, Et, Bun) may still be isolated. Anhydrous hydrogen chloride is a poor solvent, only able to dissolve small molecular compounds such as nitrosyl chloride and phenol, or salts with very low lattice energies such as tetraalkylammonium halides. It readily protonates electrophiles containing lone-pairs or π bonds. Solvolysis, ligand replacement reactions, and oxidations are well-characterised in hydrogen chloride solution:[47]

- Ph3SnCl + HCl ⟶ Ph2SnCl2 + PhH (solvolysis)

- Ph3COH + 3 HCl ⟶ Ph

3C+

HCl−

2 + H3O+Cl− (solvolysis) - Me

4N+

HCl−

2 + BCl3 ⟶ Me

4N+

BCl−

4 + HCl (ligand replacement) - PCl3 + Cl2 + HCl ⟶ PCl+

4HCl−

2 (oxidation)

Other binary chlorides

Nearly all elements in the periodic table form binary chlorides. The exceptions are decidedly in the minority and stem in each case from one of three causes: extreme inertness and reluctance to participate in chemical reactions (the noble gases, with the exception of xenon in the highly unstable XeCl2 and XeCl4); extreme nuclear instability hampering chemical investigation before decay and transmutation (many of the heaviest elements beyond bismuth); and having an electronegativity higher than chlorine's (oxygen and fluorine) so that the resultant binary compounds are formally not chlorides but rather oxides or fluorides of chlorine.[48] Even though nitrogen in NCl3 is bearing a negative charge, the compound is usually called nitrogen trichloride.

Chlorination of metals with Cl2 usually leads to a higher oxidation state than bromination with Br2 when multiple oxidation states are available, such as in MoCl5 and MoBr3. Chlorides can be made by reaction of an element or its oxide, hydroxide, or carbonate with hydrochloric acid, and then dehydrated by mildly high temperatures combined with either low pressure or anhydrous hydrogen chloride gas. These methods work best when the chloride product is stable to hydrolysis; otherwise, the possibilities include high-temperature oxidative chlorination of the element with chlorine or hydrogen chloride, high-temperature chlorination of a metal oxide or other halide by chlorine, a volatile metal chloride, carbon tetrachloride, or an organic chloride. For instance, zirconium dioxide reacts with chlorine at standard conditions to produce zirconium tetrachloride, and uranium trioxide reacts with hexachloropropene when heated under reflux to give uranium tetrachloride. The second example also involves a reduction in oxidation state, which can also be achieved by reducing a higher chloride using hydrogen or a metal as a reducing agent. This may also be achieved by thermal decomposition or disproportionation as follows:[48]

- EuCl3 + 1/2 H2 ⟶ EuCl2 + HCl

- ReCl5 ReCl3 + Cl2

- AuCl3 AuCl + Cl2

Most metal chlorides with the metal in low oxidation states (+1 to +3) are ionic. Nonmetals tend to form covalent molecular chlorides, as do metals in high oxidation states from +3 and above. Both ionic and covalent chlorides are known for metals in oxidation state +3 (e.g. scandium chloride is mostly ionic, but aluminium chloride is not). Silver chloride is very insoluble in water and is thus often used as a qualitative test for chlorine.[48]

Polychlorine compounds

Although dichlorine is a strong oxidising agent with a high first ionisation energy, it may be oxidised under extreme conditions to form the [Cl2+ cation. This is very unstable and has only been characterised by its electronic band spectrum when produced in a low-pressure discharge tube. The yellow [Cl3+ cation is more stable and may be produced as follows:[49]

- Cl2 + ClF + AsF5 [Cl3+[AsF6−

This reaction is conducted in the oxidising solvent arsenic pentafluoride. The trichloride anion, [Cl3−, has also been characterised; it is analogous to triiodide.[50]

Chlorine fluorides

The three fluorides of chlorine form a subset of the interhalogen compounds, all of which are diamagnetic.[50] Some cationic and anionic derivatives are known, such as ClF−

2, ClF−

4, ClF+

2, and Cl2F+.[51] Some pseudohalides of chlorine are also known, such as cyanogen chloride (ClCN, linear), chlorine cyanate (ClNCO), chlorine thiocyanate (ClSCN, unlike its oxygen counterpart), and chlorine azide (ClN3).[50]

Chlorine monofluoride (ClF) is extremely thermally stable, and is sold commercially in 500-gram steel lecture bottles. It is a colourless gas that melts at −155.6 °C and boils at −100.1 °C. It may be produced by the reaction of its elements at 225 °C, though it must then be separated and purified from chlorine trifluoride and its reactants. Its properties are mostly intermediate between those of chlorine and fluorine. It will react with many metals and nonmetals from room temperature and above, fluorinating them and liberating chlorine. It will also act as a chlorofluorinating agent, adding chlorine and fluorine across a multiple bond or by oxidation: for example, it will attack carbon monoxide to form carbonyl chlorofluoride, COFCl. It will react analogously with hexafluoroacetone, (CF3)2CO, with a potassium fluoride catalyst to produce heptafluoroisopropyl hypochlorite, (CF3)2CFOCl; with nitriles RCN to produce RCF2NCl2; and with the sulfur oxides SO2 and SO3 to produce ClSO2F and ClOSO2F respectively. It will also react exothermically with compounds containing –OH and –NH groups, such as water:[50]

- H2O + 2 ClF ⟶ 2 HF + Cl2O

Chlorine trifluoride (ClF3) is a volatile colourless molecular liquid which melts at −76.3 °C and boils at 11.8 °C. It may be formed by directly fluorinating gaseous chlorine or chlorine monofluoride at 200–300 °C. One of the most reactive chemical compounds known, the list of elements it sets on fire is diverse, containing hydrogen, potassium, phosphorus, arsenic, antimony, sulfur, selenium, tellurium, bromine, iodine, and powdered molybdenum, tungsten, rhodium, iridium, and iron. It will also ignite water, along with many substances which in ordinary circumstances would be considered chemically inert such as asbestos, concrete, glass, and sand. When heated, it will even corrode noble metals as palladium, platinum, and gold, and even the noble gases xenon and radon do not escape fluorination. An impermeable fluoride layer is formed by sodium, magnesium, aluminium, zinc, tin, and silver, which may be removed by heating. Nickel, copper, and steel containers are usually used due to their great resistance to attack by chlorine trifluoride, stemming from the formation of an unreactive layer of metal fluoride. Its reaction with hydrazine to form hydrogen fluoride, nitrogen, and chlorine gases was used in experimental rocket engine, but has problems largely stemming from its extreme hypergolicity resulting in ignition without any measurable delay. Today, it is mostly used in nuclear fuel processing, to oxidise uranium to uranium hexafluoride for its enriching and to separate it from plutonium, as well as in the semiconductor industry, where it is used to clean chemical vapor deposition chambers.[52] It can act as a fluoride ion donor or acceptor (Lewis base or acid), although it does not dissociate appreciably into ClF+

2 and ClF−

4 ions.[53]

Chlorine pentafluoride (ClF5) is made on a large scale by direct fluorination of chlorine with excess fluorine gas at 350 °C and 250 atm, and on a small scale by reacting metal chlorides with fluorine gas at 100–300 °C. It melts at −103 °C and boils at −13.1 °C. It is a very strong fluorinating agent, although it is still not as effective as chlorine trifluoride. Only a few specific stoichiometric reactions have been characterised. Arsenic pentafluoride and antimony pentafluoride form ionic adducts of the form +− (M = As, Sb) and water reacts vigorously as follows:[54]

- 2 H2O + ClF5 ⟶ 4 HF + FClO2

The product, chloryl fluoride, is one of the five known chlorine oxide fluorides. These range from the thermally unstable FClO to the chemically unreactive perchloryl fluoride (FClO3), the other three being FClO2, F3ClO, and F3ClO2. All five behave similarly to the chlorine fluorides, both structurally and chemically, and may act as Lewis acids or bases by gaining or losing fluoride ions respectively or as very strong oxidising and fluorinating agents.[55]

Chlorine oxides

The chlorine oxides are well-studied in spite of their instability (all of them are endothermic compounds). They are important because they are produced when chlorofluorocarbons undergo photolysis in the upper atmosphere and cause the destruction of the ozone layer. None of them can be made from directly reacting the elements.[56]

Dichlorine monoxide (Cl2O) is a brownish-yellow gas (red-brown when solid or liquid) which may be obtained by reacting chlorine gas with yellow mercury(II) oxide. It is very soluble in water, in which it is in equilibrium with hypochlorous acid (HOCl), of which it is the anhydride. It is thus an effective bleach and is mostly used to make hypochlorites. It explodes on heating or sparking or in the presence of ammonia gas.[56]

Chlorine dioxide (ClO2) was the first chlorine oxide to be discovered in 1811 by Humphry Davy. It is a yellow paramagnetic gas (deep-red as a solid or liquid), as expected from its having an odd number of electrons: it is stable towards dimerisation due to the delocalisation of the unpaired electron. It explodes above −40 °C as a liquid and under pressure as a gas and therefore must be made at low concentrations for wood-pulp bleaching and water treatment. It is usually prepared by reducing a chlorate as follows:[56]

- ClO−

3 + Cl− + 2 H+ ⟶ ClO2 + 1/2 Cl2 + H2O

Its production is thus intimately linked to the redox reactions of the chlorine oxoacids. It is a strong oxidising agent, reacting with sulfur, phosphorus, phosphorus halides, and potassium borohydride. It dissolves exothermically in water to form dark-green solutions that very slowly decompose in the dark. Crystalline clathrate hydrates ClO2·nH2O (n ≈ 6–10) separate out at low temperatures. However, in the presence of light, these solutions rapidly photodecompose to form a mixture of chloric and hydrochloric acids. Photolysis of individual ClO2 molecules result in the radicals ClO and ClOO, while at room temperature mostly chlorine, oxygen, and some ClO3 and Cl2O6 are produced. Cl2O3 is also produced when photolysing the solid at −78 °C: it is a dark brown solid that explodes below 0 °C. The ClO radical leads to the depletion of atmospheric ozone and is thus environmentally important as follows:[56]

- Cl• + O3 ⟶ ClO• + O2

- ClO• + O• ⟶ Cl• + O2

Chlorine perchlorate (ClOClO3) is a pale yellow liquid that is less stable than ClO2 and decomposes at room temperature to form chlorine, oxygen, and dichlorine hexoxide (Cl2O6).[56] Chlorine perchlorate may also be considered a chlorine derivative of perchloric acid (HOClO3), similar to the thermally unstable chlorine derivatives of other oxoacids: examples include chlorine nitrate (ClONO2, vigorously reactive and explosive), and chlorine fluorosulfate (ClOSO2F, more stable but still moisture-sensitive and highly reactive).[57] Dichlorine hexoxide is a dark-red liquid that freezes to form a solid which turns yellow at −180 °C: it is usually made by reaction of chlorine dioxide with oxygen. Despite attempts to rationalise it as the dimer of ClO3, it reacts more as though it were chloryl perchlorate, +−, which has been confirmed to be the correct structure of the solid. It hydrolyses in water to give a mixture of chloric and perchloric acids: the analogous reaction with anhydrous hydrogen fluoride does not proceed to completion.[56]

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Chlorine

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk