A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

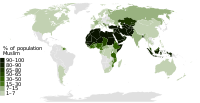

| 90–100% | |

| 70–90% | |

| 50–70% | Bosnia and Herzegovina |

| 30–40% | North Macedonia |

| 10–20% | |

| 5–10% | |

| 4–5% | |

| 2–4% | |

| 1–2% | |

| < 1% |

| Islam by country |

|---|

|

|

|

| Islam by country |

|---|

|

|

|

Islam is the second largest religion in the Netherlands, after Christianity, and is practised by 5% of the population according to 2018 estimates.[2] The majority of Muslims in the Netherlands belong to the Sunni denomination.[3] Many reside in the country's four major cities: Amsterdam, Rotterdam, The Hague and Utrecht.

The early history of Islam in the Netherlands can be traced back to the 16th century, when a small number of Ottoman merchants began settling in the nation's port cities. As a result, improvised mosques were first built in Amsterdam in the early 17th century.[4] In the ensuing centuries, the Netherlands experienced sporadic Muslim immigration from the Dutch East Indies, during their long history as part of the Dutch overseas possessions. From the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire after the First World War until the independence of Indonesia, the Dutch East Indies contained the world's second largest Muslim population, after British India. However, the number of Muslims in the European territory of the Kingdom of the Netherlands was very low, accounting for less than 0.1% of the population.

The Netherlands' economic resurgence in the years between 1960 and 1973 motivated the Dutch government to recruit foreign skilled laborers, chiefly from Morocco and Turkey – both majority Muslim countries. Later waves of Muslim immigrants arrived through family reunification and asylum seeking. Small but notable minorities of Muslims also immigrated from the former colonies of Indonesia and Suriname.

History

Ottoman traders and Dutch converts

The first traces of Islam in the Netherlands date back to the 16th century. Ottoman and Persian traders settled in many Dutch and Flemish trading towns, and were allowed to practice their faith, although most of them belonged to the Jewish or Greek Orthodox community under the Sultan. The English traveler Andrew Marvell referred to the Netherlands as "the place for Turk, Christian, heathen, Jew; staple place for sects and schisms" due to the religious freedom and the large number of different religious groups there.[5] References to the Ottoman state and Islamic symbolism were also frequently used within 16th century Dutch society itself, most notably in Protestant speeches called hagenpreken, and in the crescent-shaped medals of the Geuzen, bearing the inscription "Rather Turkish than Papists". When Dutch forces broke through the Spanish siege of Leiden in 1574, they carried with them Turkish flags into the city.[6] During the Siege of Sluis in Zeeland in 1604, 1400 Turkish slaves were freed by Maurice of Orange from captivity by the Spanish army.[7] The Turks were declared free people and the Dutch state paid for their repatriation. To honor the resistance of the Turkish slaves to their Spanish masters, Prince Maurice named a local embankment "Turkeye". Around this time the Netherlands also housed a small group of Muslim refugees from the Iberian peninsula, called Moriscos, who would eventually settle in Constantinople.[citation needed]

Diplomat Cornelius Haga gained trading privileges from Constantinople for the Dutch Republic in 1612, some 40 years before any other nation recognized Dutch independence.[8] Two years later the Ottomans sent their emissary Ömer Aga to the Netherlands to intensify the relations between the two states with a common enemy.[9]

In the 17th century dozens of Dutch, Zeelandic and Frisian sailors converted to Islam and joined the Barbary Pirates in the ports of North-Africa, where some of them even became admirals in the Ottoman Navy.[10] Many sailors converted to escape slavery after being taken captive, while others "went Turk" of their own volition. Some of the converted Dutchmen returned home to the Netherlands. However, this was deemed problematic, not so much due to their conversion, but due to their disloyalty to the Dutch Republic and its navy.[citation needed]

Envoys from Aceh

In 1602, Aceh Sultanate sent several envoys to the Netherlands. This was the first diplomatic mission of a Southeast Asian polity to Europe. The Acehnese delegation to the United Republic constituted an ambassador, an admiral and a cousin of the sultan, accompanied by their servants. In his letter to stadtholder Prince Maurice dated 24 August 1601 Alau'd-din enumerated the gifts he sent for the prince. These were 'a small jewel and a ring with four big stones and some smaller stones, a dagger with a gold and copper sheath wrapped in a silver cloth, a golden cup and saucer and a gold-plated silver pot and two Malay speaking parrots with silver chains.

The envoys were treated with due respect and given a grand tour of the provinces where they visited important towns and met with local authorities; they were received by the States General and by Prince Maurice. The States General invited European monarchs to send their representatives to meet the Acehnese visitors. It was a successful strategy to give publicity to their warm relations with an important Asian ruler and trading partner at a time when Spain was still a menace in Europe.

The eldest of the envoys, Abdul Hamid, died three months after arrival and was buried in a church in the town of Middelburg in the province of Zeeland, in the presence of important dignitaries. The other envoys, Sri Muhammad and Mir Hassan, returned to Aceh in 1604 with the fleet of Admiral Steven Verhaegen.[11]

Treaty with Morocco

In the early 17th century a delegation from the Dutch Republic visited Morocco to discuss a common alliance against Spain and the Barbary pirates. Sultan Zidan Abu Maali appointed Samuel Pallache as his envoy, and in 1608 Pallache met with stadholder Maurice of Nassau and the States General in The Hague.[12]

Dutch East Indies

In the 19th century the Netherlands administered the archipelago that would become Indonesia, a majority-Muslim country with the largest Muslim population in the world. The 19th century is also the century in which the first Muslim burial site appeared in the Netherlands, namely the tomb of Lepejou, in which a former slave from the Dutch East Indies was buried near Zwolle in 1828.[13][14] In the first half of the 20th century hundreds of Indonesian students, sailors, baboes and domestic workers lived in the Netherlands, thus constituting the first sizable Muslim community. In 1932, Indonesian workers established the Perkoempoelan Islam (Islamic Association), which was a self-help organization that lobbied for the establishment of a Muslim cemetery and a mosque in the Netherlands. Both were realized in 1933.[15] After the bloody war of Independence from 1945 to 1949 this community grew.[16]

The Second World War

After Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union in the 1940s, a number of Soviet Central Asians, who were mostly from Samarqand in what is now the Muslim-majority Republic of Uzbekistan,[17] left their homes for the area of Smolensk, to fight the invaders. There, the Nazis managed to take captives, including Hatam Kadirov and Zair Muratov, and transported them to areas like that of Amersfoort concentration camp, where they reportedly persecuted or executed them. The victims' cemetery is that of Rusthof, near Amersfoort. Amongst those who studied their case is Uzbek resident Bahodir Uzakov.[18][19]

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Islamophobia_in_the_Netherlands

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk