A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

Samarkand

Самарканд | |

|---|---|

City | |

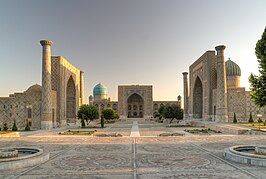

Clockwise from the top: Registan square, Shah-i-Zinda necropolis, Bibi-Khanym Mosque, view inside Shah-i-Zinda, Sher-Dor Madrasah in Registan, Timur's Mausoleum Gur-e-Amir. | |

| Coordinates: 39°39′17″N 66°58′33″E / 39.65472°N 66.97583°E | |

| Country | |

| Vilayat | Samarqand Vilayat |

| Settled | 8th century BCE |

| Government | |

| • Type | City Administration |

| • Body | Hakim (Mayor) |

| Area | |

| • City | 120 km2 (50 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 705 m (2,313 ft) |

| Population (1 January 2019) | |

| • City | 513,572[1] |

| • Metro | 950,000 |

| Demonym | Samarqandian / Samarqandi |

| Time zone | UTC+5 |

| Postal code | 140100 |

| Website | samarkand.uz |

| Official name | Samarqand – Crossroads of Cultures |

| Criteria | Cultural: i, ii, iv |

| Reference | 603 |

| Inscription | 2001 (25th Session) |

| Area | 1,123 ha |

| Buffer zone | 1,369 ha |

Samarkand or Samarqand (/ˈsæmərkænd/ SAM-ər-kand; Uzbek and Tajik: Самарқанд, pronounced [sæmærqænd, -ænt]; Persian: سمرقند) is a city in southeastern Uzbekistan and among the oldest continuously inhabited cities in Central Asia. Samarqand is the capital of Samarqand Region and a district-level city, that includes the urban-type settlements Kimyogarlar, Farhod and Khishrav.[2] With 551,700 inhabitants (2021),[3] it is the third-largest city of Uzbekistan.

There is evidence of human activity in the area of the city dating from the late Paleolithic Era. Though there is no direct evidence of when Samarqand was founded, several theories propose that it was founded between the 8th and 7th centuries BCE. Prospering from its location on the Silk Road between China, Persia and Europe, at times Samarqand was one of the largest[4] cities in Central Asia,[5] and was an important city of the empires of Greater Iran.[6] By the time of the Persian Achaemenid Empire, it was the capital of the Sogdian satrapy. The city was conquered by Alexander the Great in 329 BCE, when it was known as Markanda, which was rendered in Greek as Μαράκανδα.[7] The city was ruled by a succession of Iranian and Turkic rulers until it was conquered by the Mongols under Genghis Khan in 1220.

The city is noted as a centre of Islamic scholarly study and the birthplace of the Timurid Renaissance. In the 14th century, Timur made it the capital of his empire and the site of his mausoleum, the Gur-e Amir. The Bibi-Khanym Mosque, rebuilt during the Soviet era, remains one of the city's most notable landmarks. Samarqand's Registan square was the city's ancient centre and is bounded by three monumental religious buildings. The city has carefully preserved the traditions of ancient crafts: embroidery, goldwork, silk weaving, copper engraving, ceramics, wood carving, and wood painting.[8] In 2001, UNESCO added the city to its World Heritage List as Samarqand – Crossroads of Cultures.

Modern Samarqand is divided into two parts: the old city, and the new city, which was developed during the days of the Russian Empire and Soviet Union. The old city includes historical monuments, shops, and old private houses; the new city includes administrative buildings along with cultural centres and educational institutions.[9] On September 15–16, 2022, the city hosted the 2022 SCO summit.

Samarkand has a rich multicultural and plurilingual history that was significantly modified by the process of national delimitation in Central Asia. Many inhabitants of the city are native or bilingual speakers of the Tajik language,[10][11] whereas Uzbek is the official language and Russian is also widely used in the public sphere, as per Uzbekistan's language policy.

Etymology

The name comes from Sogdian samar "stone, rock" and kand "fort, town."[12] In this respect, Samarqand shares the same meaning as the name of the Uzbek capital Tashkent, with tash- being the Turkic term for "stone" and -kent the Turkic analogue of kand.[13]

According to 11th-century scholar Mahmud al-Kashghari, the city was known in Karakhanid as Sämizkänd (سَمِزْکَنْدْ), meaning "fat city."[14] 16th-century Mughal emperor Babur also mentioned the city under this name, and 15th-century Castillian traveler Ruy González de Clavijo stated that Samarqand was simply a distorted form of it.[15]

History

This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2022) |

Early history

Along with Bukhara,[16] Samarqand is one of the oldest inhabited cities in Central Asia, prospering from its location on the trade route between China and Europe. There is no direct evidence of when it was founded. Researchers at the Institute of Archaeology of Samarqand date the city's founding to the 8th–7th centuries BCE.

Archaeological excavations conducted within the city limits (Syob and midtown) as well as suburban areas (Hojamazgil, Sazag'on) unearthed 40,000-year-old evidence of human activity, dating back to the Upper Paleolithic. A group of Mesolithic (12th–7th millennia BCE) archaeological sites were discovered in the suburbs of Sazag'on-1, Zamichatosh, and Okhalik. The Syob and Darg'om canals, supplying the city and its suburbs with water, appeared around the 7th–5th centuries BCE (early Iron Age).

From its earliest days, Samarqand was one of the main centres of Sogdian civilization. By the time of the Achaemenid dynasty of Persia, the city had become the capital of the Sogdian satrapy.

Hellenistic period

Ferens Art Gallery, Hull.

Alexander the Great conquered Samarqand in 329 BCE. The city was known as Maracanda (Μαράκανδα) by the Greeks.[17] Written sources offer small clues as to the subsequent system of government. [18] They mention one Orepius who became ruler "not from ancestors, but as a gift of Alexander."[19]

While Samarqand suffered significant damage during Alexander's initial conquest, the city recovered rapidly and flourished under the new Hellenic influence. There were also major new construction techniques. Oblong bricks were replaced with square ones and superior methods of masonry and plastering were introduced.[20]

Alexander's conquests introduced classical Greek culture into Central Asia and for a time, Greek aesthetics heavily influenced local artisans. This Hellenistic legacy continued as the city became part of various successor states in the centuries following Alexander's death, the Seleucid Empire, Greco-Bactrian Kingdom, and Kushan Empire (even though the Kushana themselves originated in Central Asia). After the Kushan state lost control of Sogdia during the 3rd century CE, Samarqand went into decline as a centre of economic, cultural, and political power. It did not significantly revive until the 5th century.

Sassanian era

Samarqand was conquered by the Persian Sassanians c. 260 CE. Under Sassanian rule, the region became an essential site for Manichaeism and facilitated the dissemination of the religion throughout Central Asia.[21]

Hephtalites and Turkic Khaganate era

In AD 350–375 Samarqand was conquered by the nomadic tribes of Xionites, the origin of which remains controversial.[22] The resettlement of nomadic groups to Samarqand confirms archaeological material from the 4th century. The culture of nomads from the Middle Syrdarya basin is spreading in the region.[23] In 457–509 Samarqand was part of the Kidarite state.[24]

After the Hephtalites ("White Huns") conquered Samarqand, they controlled it until the Göktürks, in an alliance with the Sassanid Persians, won it at the Battle of Bukhara, c. 560 CE.[27]

In the middle of the 6th century, a Turkic state was formed in Altai, founded by the Ashina dynasty. The new state formation was named the Turkic Khaganate after the people of the Turks, which were headed by the ruler – the Khagan. In 557–561, the Hephthalites empire was defeated by the joint actions of the Turks and Sassanids, which led to the establishment of a common border between the two empires.[28]

In the early Middle Ages, Samarqand was surrounded by four rows of defensive walls and had four gates.[29]

An ancient Turkic burial with a horse was investigated on the territory of Samarqand. It dates back to the 6th century.[30]

During the period of the ruler of the Western Turkic Kaganate, Tong Yabghu Qaghan (618–630), family relations were established with the ruler of Samarqand – Tong Yabghu Qaghan gave him his daughter.[31]

Some parts of Samarqand have been Christian since the 4th century. In the 5th century, a Nestorian chair was established in Samarqand. At the beginning of the 8th century, it was transformed into a Nestorian metropolitanate.[32] Discussions and polemics arose between the Sogdian followers of Christianity and Manichaeism, reflected in the documents.[33]

Early Islamic era

The armies of the Umayyad Caliphate under Qutayba ibn Muslim captured the city from the Tang dynasty c. 710 CE.[21]

During this period, Samarqand was a diverse religious community and was home to a number of religions, including Zoroastrianism, Buddhism, Hinduism, Manichaeism, Judaism, and Nestorian Christianity, with most of the population following Zoroastrianism.[35]

Qutayba generally did not settle Arabs in Central Asia; he forced the local rulers to pay him tribute but largely left them to their own devices. Samarqand was the major exception to this policy: Qutayba established an Arab garrison and Arab governmental administration in the city, its Zoroastrian fire temples were razed, and a mosque was built.[36] Much of the city's population converted to Islam.[37]

As a long-term result, Samarqand developed into a center of Islamic and Arabic learning.[36] At the end of the 740s, a movement of those dissatisfied with the power of the Umayyads emerged in the Arab Caliphate, led by the Abbasid commander Abu Muslim, who, after the victory of the uprising, became the governor of Khorasan and Maverannahr (750–755). He chose Samarqand as his residence. His name is associated with the construction of a multi-kilometer defensive wall around the city and the palace.[38]

Legend has it that during Abbasid rule,[39] the secret of papermaking was obtained from two Chinese prisoners from the Battle of Talas in 751, which led to the foundation of the first paper mill in the Islamic world at Samarqand. The invention then spread to the rest of the Islamic world and thence to Europe.[citation needed]

Abbasid control of Samarqand soon dissipated and was replaced with that of the Samanids (875–999), though the Samanids were still nominal vassals of the Caliph during their control of Samarqand. Under Samanid rule the city became a capital of the Samanid dynasty and an even more important node of numerous trade routes. The Samanids were overthrown by the Karakhanids around 999. Over the next 200 years, Samarqand would be ruled by a succession of Turkic tribes, including the Seljuqs and the Khwarazmshahs.[40]

The 10th-century Persian author Istakhri, who travelled in Transoxiana, provides a vivid description of the natural riches of the region he calls "Smarkandian Sogd":

I know no place in it or in Samarqand itself where if one ascends some elevated ground one does not see greenery and a pleasant place, and nowhere near it are mountains lacking in trees or a dusty steppe... Samakandian Sogd... eight days travel through unbroken greenery and gardens... . The greenery of the trees and sown land extends along both sides of the river ... and beyond these fields is pasture for flocks. Every town and settlement has a fortress... It is the most fruitful of all the countries of Allah; in it are the best trees and fruits, in every home are gardens, cisterns and flowing water.

Karakhanid (Ilek-Khanid) period (11th–12th centuries)

After the fall of the Samanids state in the year 999, it was replaced by the Qarakhanid State, where the Turkic Qarakhanid dynasty ruled.[41] After the state of the Qarakhanids split into two parts, Samarqand became a part of the West Karakhanid Kaganate and in 1040–1212 was its capital.[41] The founder of the Western Qarakhanid Kaganate was Ibrahim Tamgach Khan (1040–1068).[41] For the first time, he built a madrasah in Samarqand with state funds and supported the development of culture in the region. During his reign, a public hospital (bemoristan) and a madrasah were established in Samarqand, where medicine was also taught.

The memorial complex Shah-i-Zinda was founded by the rulers of the Karakhanid dynasty in the 11th century.[42]

The most striking monument of the Qarakhanid era in Samarqand was the palace of Ibrahim ibn Hussein (1178–1202), which was built in the citadel in the 12th century. During the excavations, fragments of monumental painting were discovered. On the eastern wall, a Turkic warrior was depicted, dressed in a yellow caftan and holding a bow. Horses, hunting dogs, birds and periodlike women were also depicted here.[43]

Mongol period

The Mongols conquered Samarqand in 1220. Juvayni writes that Genghis killed all who took refuge in the citadel and the mosque, pillaged the city completely, and conscripted 30,000 young men along with 30,000 craftsmen. Samarqand suffered at least one other Mongol sack by Khan Baraq to get treasure he needed to pay an army. It remained part of the Chagatai Khanate (one of four Mongol successor realms) until 1370.

The Travels of Marco Polo, where Polo records his journey along the Silk Road in the late 13th century, describes Samarqand as "a very large and splendid city..."[44]

The Yenisei area had a community of weavers of Chinese origin, and Samarqand and Outer Mongolia both had artisans of Chinese origin, as reported by Changchun.[45] After Genghis Khan conquered Central Asia, foreigners were chosen as governmental administrators; Chinese and Qara-Khitays (Khitans) were appointed as co-managers of gardens and fields in Samarqand, which Muslims were not permitted to manage on their own.[46][47] The khanate allowed the establishment of Christian bishoprics (see below).

Timur's rule (1370–1405)

Ibn Battuta, who visited in 1333, called Samarqand "one of the greatest and finest of cities, and most perfect of them in beauty." He also noted that the orchards were supplied water via norias.[48]

In 1365, a revolt against Chagatai Mongol control occurred in Samarqand.[49] In 1370, the conqueror Timur (Tamerlane), the founder and ruler of the Timurid Empire, made Samarqand his capital. Timur used various tools for legitimisation, including urban planning in his capital, Samarkand.[50] Over the next 35 years, he rebuilt most of the city and populated it with great artisans and craftsmen from across the empire. Timur gained a reputation as a patron of the arts, and Samarqand grew to become the centre of the region of Transoxiana. Timur's commitment to the arts is evident in how, in contrast with the ruthlessness he showed his enemies, he demonstrated mercy toward those with special artistic abilities. The lives of artists, craftsmen, and architects were spared so that they could improve and beautify Timur's capital.[citation needed]

Timur was also directly involved in construction projects, and his visions often exceeded the technical abilities of his workers. The city was in a state of constant construction, and Timur would often order buildings to be done and redone quickly if he was unsatisfied with the results.[51] By his orders, Samarqand could be reached only by roads; deep ditches were dug, and walls 8 km (5 mi) in circumference separated the city from its surrounding neighbors.[52] At this time, the city had a population of about 150,000.[53]

Henry III of Castile's ambassador Ruy Gonzalez de Clavijo, who was stationed at Samarqand between 1403 and 1406, attested to the never-ending construction that went on in the city. "The Mosque which Timur had built seemed to us the noblest of all those we visited in the city of Samarqand. "[54]

Ulugh Beg's period (1409–1449)

In 1417–1420, Timur's grandson Ulugh Beg built a madrasah in Samarqand, which became the first building in the architectural ensemble of Registan. Ulugh Beg invited a large number of astronomers and mathematicians of the Islamic world to this madrasah. Under Ulugh Beg, Samarqand became one of the world centers of medieval science. In the first half of the 15th century, a whole scientific school arose around Ulugh Beg, uniting prominent astronomers and mathematicians including Jamshid al-Kashi, Qāḍī Zāda al-Rūmī, and Ali Qushji. Ulugh Beg's main interest in science was astronomy, and he constructed an observatory in 1428. Its main instrument was the wall quadrant, which was unique in the world.[55] It was known as the "Fakhri Sextant" and had a radius of 40 meters.[56] Seen in the image on the left, the arc was finely constructed with a staircase on either side to provide access for the assistants who performed the measurements.

16th–18th centuries

In 1500, nomadic Uzbek warriors took control of Samarqand.[53] The Shaybanids emerged as the city's leaders at or about this time. In 1501, Samarqand was finally taken by Muhammad Shaybani from the Uzbek dynasty of Shaybanids, and the city became part of the newly formed “Bukhara Khanate”. Samarqand was chosen as the capital of this state, in which Muhammad Shaybani Khan was crowned. In Samarqand, Muhammad Shaybani Khan ordered to build a large madrasah, where he later took part in scientific and religious disputes. The first dated news about the Shaybani Khan madrasah dates back to 1504 (it was completely destroyed during the years of Soviet power). Muhammad Salikh wrote that Sheibani Khan built a madrasah in Samarqand to perpetuate the memory of his brother Mahmud Sultan.[57]

Fazlallah ibn Ruzbihan [who?] in "Mikhmon-namei Bukhara" expresses his admiration for the majestic building of the madrasah, its gilded roof, high hujras, spacious courtyard and quotes a verse praising the madrasah.[58] Zayn ad-din Vasifi, who visited the Sheibani-khan madrasah several years later, wrote in his memoirs that the veranda, hall and courtyard of the madrassah are spacious and magnificent.[57]

Abdulatif Khan, the son of Mirzo Ulugbek's grandson Kuchkunji Khan, who ruled in Samarqand in 1540–1551, was considered an expert in the history of Maverannahr and the Shibanid dynasty. He patronized poets and scientists. Abdulatif Khan himself wrote poetry under the literary pseudonym Khush.[59]

During the reign of the Ashtarkhanid Imam Quli Khan (1611–1642) famous architectural masterpieces were built in Samarqand. In 1612–1656, the governor of Samarqand, Yalangtush Bahadur, built a cathedral mosque, Tillya-Kari madrasah and Sherdor madrasah.[citation needed]

Zarafshan Water Bridge is a brick bridge built on the left bank of the Zarafshan River, 7–8 km northeast of the center of Samarkand, built by Shaibani Khan at the beginning of the 16th century.[60][61]

After an assault by the Afshar Shahanshah Nader Shah, the city was abandoned in the early 1720s.[62] From 1599 to 1756, Samarqand was ruled by the Ashtrakhanid branch of the Khanate of Bukhara.

-

Ulugh Beg Madrasah

-

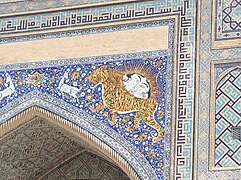

Sher-Dor Madrasah

-

Tilya Kori Madrasah

-

Ulugh Beg Madrasah courtyard

-

Tiger on the Sher-Dor Madrasah iwan

Second half of the 18th–19th centuries

From 1756 to 1868, it was ruled by the Manghud Emirs of Bukhara.[63] The revival of the city began during the reign of the founder of the Uzbek dynasty, the Mangyts, Muhammad Rakhim (1756–1758), who became famous for his strong-willed qualities and military art. Muhammad Rakhimbiy made some attempts to revive Samarqand.[64]

Russian Empire period

The city came under imperial Russian rule after the citadel had been taken by a force under Colonel Konstantin Petrovich von Kaufman in 1868. Shortly thereafter the small Russian garrison of 500 men were themselves besieged. The assault, which was led by Abdul Malik Tura, the rebellious elder son of the Bukharan Emir, as well as Baba Beg of Shahrisabz and Jura Beg of Kitab, was repelled with heavy losses. General Alexander Konstantinovich Abramov became the first Governor of the Military Okrug, which the Russians established along the course of the Zeravshan River with Samarqand as the administrative centre. The Russian section of the city was built after this point, largely west of the old city.

In 1886, the city became the capital of the newly formed Samarkand Oblast of Russian Turkestan and regained even more importance when the Trans-Caspian railway reached it in 1888.

Soviet period

Samarqand was the capital of the Uzbek SSR from 1925 to 1930, before being replaced by Tashkent. During World War II, after Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union, a number of Samarqand's citizens were sent to Smolensk to fight the enemy. Many were taken captive or killed by the Nazis.[65][66] Additionally, thousands of refugees from the occupied western regions of the USSR fled to the city, and it served as one of the main hubs for the fleeing civilians in the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic and the Soviet Union as a whole.[citation needed]

European study of the history of Samarqand began after the conquest of Samarqand by the Russian Empire in 1868. The first studies of the history of Samarqand belong to N. Veselovsky, V. Bartold and V. Vyatkin. In the Soviet period, the generalization of materials on the history of Samarqand was reflected in the two-volume History of Samarqand edited by the academician of Uzbekistan Ibrohim Moʻminov.[67]

On the initiative of Academician of the Academy of Sciences of the Uzbek SSR I. Muminov and with the support of Sharaf Rashidov, the 2500th anniversary of Samarqand was widely celebrated in 1970. In this regard, a monument to Ulugh Beg was opened, the Museum of the History of Samarqand was founded, and a two-volume history of Samarqand was prepared and published.[68][69]

After Uzbekistan gained independence, several monographs were published on the ancient and medieval history of Samarqand.[70][71]

Geography

Samarqand is located in southeastern Uzbekistan, in the Zarefshan River valley, 135 km from Qarshi. Road M37 connects Samarqand to Bukhara, 240 km away. Road M39 connects it to Tashkent, 270 km away. The Tajikistan border is about 35 km from Samarqand; the Tajik capital Dushanbe is 210 km away from Samarqand. Road M39 connects Samarqand to Mazar-i-Sharif in Afghanistan, which is 340 km away.

Climate

Samarqand has a cold semi-arid climate (Köppen climate classification: BSk) with hot, dry summers and relatively wet, variable winters that alternate periods of warm weather with periods of cold weather. July and August are the hottest months of the year, with temperatures reaching and exceeding 40 °C (104 °F). Precipitation is sparse from June through October, but increases to a maximum from February to April. January 2008 was particularly cold; the temperature dropped to −22 °C (−8 °F).[73]

| Climate data for Samarkand (1991–2020, extremes 1891–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 23.2 (73.8) |

26.7 (80.1) |

32.2 (90.0) |

36.2 (97.2) |

39.5 (103.1) |

41.6 (106.9) |

42.4 (108.3) |

41.0 (105.8) |

38.6 (101.5) |

35.2 (95.4) |

31.5 (88.7) |

27.5 (81.5) |

42.4 (108.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 7.3 (45.1) |

9.5 (49.1) |

15.2 (59.4) |

21.4 (70.5) |

27.0 (80.6) |

32.4 (90.3) |

34.5 (94.1) |

33.3 (91.9) |

28.6 (83.5) |

22.0 (71.6) |

14.4 (57.9) |

9.1 (48.4) |

21.2 (70.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 2.3 (36.1) |

4.0 (39.2) |

9.3 (48.7) |

15.2 (59.4) |

20.4 (68.7) |

25.4 (77.7) |

27.2 (81.0) |

25.6 (78.1) |

20.6 (69.1) |

14.1 (57.4) |

8.0 (46.4) |

3.7 (38.7) |

14.7 (58.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −1.3 (29.7) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

4.6 (40.3) |

9.7 (49.5) |

14.1 (57.4) |

18.0 (64.4) |

19.5 (67.1) |

17.9 (64.2) |

13.5 (56.3) |

7.8 (46.0) |

3.2 (37.8) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

8.9 (48.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −25.4 (−13.7) |

−22 (−8) |

−14.9 (5.2) |

−6.8 (19.8) |

−1.3 (29.7) |

4.8 (40.6) |

8.6 (47.5) |

7.8 (46.0) |

0.0 (32.0) |

−6.4 (20.5) |

−18.1 (−0.6) |

−22.8 (−9.0) |

−25.4 (−13.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 41 (1.6) |

53 (2.1) |

73 (2.9) |

64 (2.5) |

41 (1.6) |

7 (0.3) |

2 (0.1) |

2 (0.1) |

3 (0.1) |

16 (0.6) |

40 (1.6) |

39 (1.5) |

381 (15) |

| Average rainy days | 8 | 10 | 13 | 11 | 9 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 8 | 9 | 82 |

| Average snowy days | 9 | 7 | 3 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | 2 | 6 | 28 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 76 | 74 | 70 | 63 | 54 | 42 | 42 | 43 | 47 | 59 | 68 | 74 | 59 |

| Average dew point °C (°F) | −2 (28) |

−1 (30) |

2 (36) |

6 (43) |

9 (48) |

9 (48) |

10 (50) |

9 (48) |

6 (43) |

4 (39) |

2 (36) |

−1 (30) |

4 (40) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 119.2 | 130.9 | 172.2 | 228.8 | 297.7

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Samarqand Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Analytika

Antropológia Aplikované vedy Bibliometria Dejiny vedy Encyklopédie Filozofia vedy Forenzné vedy Humanitné vedy Knižničná veda Kryogenika Kryptológia Kulturológia Literárna veda Medzidisciplinárne oblasti Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy Metavedy Metodika Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok. www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk | ||||||||