A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Pre-vice presidency

43rd Vice President of the United States 41st President of the United States

Policies

Appointments

Tenure

Presidential campaigns Vice presidential campaigns Post-presidency

|

||

George H. W. Bush, whose term as president lasted from 1989 until 1993, had extensive experience with US foreign policy. Unlike his predecessor, Ronald Reagan, he downplayed vision and emphasized caution and careful management. [citation needed]He had quietly disagreed with many of Reagan's foreign policy decisions and tried to build his own policies.[1] His main foreign policy advisors were Secretaries of State James Baker, a longtime friend, and National Security Advisor Brent Scowcroft. Key geopolitical events that occurred during Bush's presidency were:[2][3]

- The Gulf War, in which Bush led a large coalition that defeated Iraq following its Invasion of Kuwait, but allowed Saddam Hussein to remain in power.

- The United States invasion of Panama to overthrow a local dictator.

- The signing with the Soviet Union of the START I and START II treaties for nuclear disarmament.

- Victory in the Cold War over communism.

- Revolutions of 1989 and the collapse of Moscow-oriented Communism, especially in Eastern Europe

- The dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, replaced by the Post-Soviet states (Russia and 14 other countries).

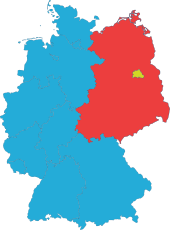

- German reunification in 1990, with the democratic West Germany absorbing the ex-Communist East Germany.

- The expansion of NATO to the east, starting with a united Germany.

Appointments

| George H. W. Bush administration foreign policy personnel | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vice President | Quayle (1989–1993) | |||||||

| Secretary of State | Baker (1989–1992) |

Eagleburger (1992–1993) | ||||||

| Secretary of Defense | Cheney (1989–1993) | |||||||

| Ambassador to the United Nations | Walters (1989) |

Pickering (1989–1992) |

Perkins (1992–1993) | |||||

| Director of Central Intelligence | Webster (1989–1991) |

Kerr (1991) |

Gates (1991–1993) | |||||

| Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs | Scowcroft (1989–1993) | |||||||

| Deputy Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs | Gates (1989–1991) |

Howe (1991–1993) | ||||||

| Trade Representative | Hills (1989–1993) | |||||||

History

Experienced leadership team

In 1971, President Richard Nixon appointed Bush as Ambassador to the United Nations, and he became chairman of the Republican National Committee in 1973. In 1974, President Gerald Ford appointed him Chief of the Liaison Office in China and later made him the Director of Central Intelligence. Bush sought the Republican presidential nomination in 1980, but lost to Ronald Reagan. He was then elected vice president in 1980 and 1984 as Reagan's running mate. The vice president, logged 1.3 million miles of travel to 50 states and 65 foreign countries, handling numerous diplomatic roles.[4][5]

Bush was a longtime close friend of both his top advisers, Secretaries of State James Baker[6] and National Security Advisor Brent Scowcroft. Baker dealt with tactical and managerial issues of the State Department and foreign policy, while Scowcroft was concerned with long-term strategy. Lawrence Eagleburger was the number two in the State Department. Robert Gates, an intelligence expert, was deputy to Scowcroft, And had a major policy-making role. The full National Security Council met three times a week. Vice President Dan Quayle handled ceremonial foreign-policy visits. Bush wanted to name Senator John Tower as secretary of defense, but Tower's colleagues in the Senate were annoyed at his imperious style and drinking problem. They rejected the nomination, so Defense went to Congressman Dick Cheney.[7] Colin Powell, more moderate than the others, became the powerful Chairman of the Joint Chiefs.[8][9][10]

Initial themes

In his inaugural address, Bush called on bipartisanship in foreign policy to begin anew. Addressing the world, he offered a "new engagement and a renewed vow: We will stay strong to protect the peace." He mentioned Americans in other countries and the lack of knowledge on their whereabouts: "There are today Americans who are held against their will in foreign lands and Americans who are unaccounted for. Assistance can be shown here and will be long remembered. Good will begets good will. Good faith can be a spiral that endlessly moves on." Bush stated the administration's intent to retain alliances from prior administrations while "we will continue the new closeness with the Soviet Union, consistent both with our security and with progress."[11]

A week into the administration, Bush was asked in what region he wished to move forward. He responded by saying "All of them", furthering there were "plenty of troublespots" and specifying Central America as one of them while insisting there needed to be complete reviews for major initiatives to take place and a bilaterally supported policy in Central America would take more time to develop.[12]

By the end of his first year in office, Bush had traveled to fifteen countries, at the time tying him with Gerald Ford as the most traveled first year president. This record was broken in 2009 by sixteen trips of Barack Obama.[13]

Victory in the Cold War

Fall of the Soviet control in Eastern Europe

Reagan and Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev had largely ended Cold War tensions in the late 1980s. However Bush remained skeptical of Soviet intentions.[14] During the first year of his tenure, Bush pursued what Soviets referred to as the pauza, a break in Reagan's détente policies.[15] While Bush implemented his pauza policy in 1989, Soviet satellites in Eastern Europe challenged Soviet domination.[16] Bush helped convince Polish United Workers' Party leaders to allow democratic elections in June, won by the anti-Communists. In 1989, Communist governments fell in all the satellites, with significant violence only in Romania. In November 1989, massive popular demand forced the Communist government of East Germany to open the Berlin Wall, and it was soon demolished by gleeful Berliners. Gorbachev refused to send in the Soviet military, effectively abandoning the Brezhnev Doctrine.[17] Within a few weeks Communist regimes across Eastern Europe collapsed, and Soviet supported parties across the globe became demoralized. The U.S. was not directly involved in these upheavals, but the Bush administration avoided the appearance of gloating over the NATO victory to avoid undermining further democratic reforms especially in the USSR.[18][19]

Bush and Gorbachev met in December 1989 in summit on the island of Malta. Bush sought cooperative relations with Gorbachev throughout the remainder of his term, putting his trust in Gorbachev to suppress the remaining Soviet hard-liners.[20] The key issue at the Malta Summit was the potential reunification of Germany.[21] While Britain and France were wary of a re-unified Germany, Bush pushed for German reunification alongside West German Chancellor Helmut Kohl.[22] Gorbachev resisted the idea of a reunified Germany, especially if it became part of NATO, but the upheavals of the previous year had sapped his power at home and abroad.[23] Gorbachev agreed to hold "Two-Plus-Four" talks among the U.S., the Soviet Union, France, Britain, West Germany, and East Germany, which commenced in 1990. After extensive negotiations, Gorbachev eventually agreed to allow a reunified Germany to be a part of NATO. He did not get Washington's agreement that NATO would not expand into the new eastern European countries of the former Warsaw Pact. With the signing of the Treaty on the Final Settlement with Respect to Germany, Germany officially reunified in October 1990.[24]

Dissolution of the Soviet Union

While Gorbachev acquiesced to loss of control over the Soviet satellite states, he suppressed nationalist movements within the Soviet Union itself.[25] Stalin had occupied and annexed the Baltic states of Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia in the 1940s. The old leadership was executed or deported or fled; hundreds of thousands of Russians moved in, but nowhere were they a majority. Hatreds simmered. Lithuania's March 1990 proclamation of independence was strongly opposed by Gorbachev, who feared that the Soviet Union could fall apart if he allowed Lithuania's independence. The United States had never recognized the Soviet incorporation of the Baltic states, and the crisis in Lithuania left Bush in a difficult position. Bush needed Gorbachev's cooperation in the reunification of Germany, and he feared that the collapse of the Soviet Union could leave nuclear arms in dangerous hands. The Bush administration mildly protested Gorbachev's suppression of Lithuania's independence movement, but took no action to directly intervene.[26] Bush warned independence movements of the disorder that could come with secession from the Soviet Union; in a 1991 address that critics labeled the "Chicken Kiev speech", he cautioned against "suicidal nationalism".[27]

In July 1991, Bush and Gorbachev signed the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START I) treaty, the first major arms agreement since the 1987 Intermediate Ranged Nuclear Forces Treaty.[28] Both countries agreed to cut their strategic nuclear weapons by 30 percent, and the Soviet Union promised to reduce its intercontinental ballistic missile force by 50 percent.[29] In August 1991, hard-line Communists launched a coup against Gorbachev; while the coup quickly fell apart, it broke the remaining power of Gorbachev and the central Soviet government.[30] Later that month, Gorbachev resigned as general secretary of the Communist party, and Russian president Boris Yeltsin ordered the seizure of Soviet property. Gorbachev clung to power as the President of the Soviet Union, until 25 December 1991, when the Soviet Union dissolved.[31] Fifteen states emerged from the Soviet Union, and of those states, Russia was the largest and most populous. Bush and Yeltsin met in February 1992, declaring a new era of "friendship and partnership".[32] In January 1993, Bush and Yeltsin agreed to START II, which provided for further nuclear arms reductions on top of the original START treaty.[33]

Americas

Argentina

Argentina wanted very good relations with the United States, as it moved toward more economic liberalism, and agreed with Washington's priorities regarding cooperative security, peacekeeping, and drug control.[34]

Canada

New presidents traditionally make their first foreign trip to Canada. Bush did so on February 10, 1989. He met with Prime Minister Brian Mulroney, and discussed air quality issues especially acid rain.[35] On July 8, 1990, the two countries had "agreed to begin negotiations for a practical and effective air quality accord" and the initial discussions would center around sulfur dioxide reduction as well as other acid rain precursors.[36] They met on March 13, 1991, to discuss developments in the Middle East.[37]

Colombia

On January 10, 1990, Bush telephoned President of Colombia Virgilio Barco Vargas, stating his regret over false stories regarding a proposed U.S. counternarcotics operation. Bush stated the US intended to engage in a "cooperative effort with Colombia that could complement President Barco's courageous and determined effort to break up the narcotics cartels and bring traffickers to justice" and that America would not conduct any activities within the territorial waters of Colombia. The two agreed on inaccurate reports about relations between the US and Colombia creating a false impression and to remain in close contact on issues relating to both of their countries.[38] The following month, Bush traveled to Colombia for discussions with the country's leadership and to sign the Document of Cartagena, insisting in a statement that it would "establish a broad, flexible framework which will help guide the actions of our four countries in the years to come" throughout their collaborative efforts in the Gulf War.[39] On July 13, Bush met with President-elect César Gaviria during the latter's private visit to the US, Bush congratulating Gaviria on his electoral victory and pledging that his administration was willing to work with Gaviria's. The two also discussed the fight against drugs and economic relations cooperation, Bush informing Gaviria on American budget requests against drugs in the upcoming fiscal year.[40]

Cuba

In a February 27, 1989, President Bush released a statement supporting the report on human rights in Cuba by the United Nations Human Rights Commission. He criticized inconsistences in the treatment of countries by the UN when it came to the issue of human rights and stated his view on the regime of Fidel Castro: "For more than 30 years, the people of Cuba have languished under a regime which has distinguished itself as one of the most repressive in the world. Last year the international community won an important victory when the U.N. Human Rights Commission decided to conduct a full investigation into the situation in Cuba. The report which was released in Geneva is based on firsthand testimony about persistent violations of human rights in that country and is the culmination of that investigation." He called for " other members of the Commission and all countries that value freedom to maintain pressure on the Cuban Government by continuing U.N. monitoring of the human rights situation in Cuba" and furthered that Cuba's people looked to the UN "as their last best hope."[41] In a July 26 address to commemorate the thirty-sixth anniversary of the start of the Cuban Revolution, Castro said President Bush's trips to Poland and Hungary were "to encourage capitalist trends that have developed there and political problems that have come up there."[42]

At a news conference on March 23, 1990, Bush was asked about what the US would do now that Cuba was the only military regime in their hemisphere and if the US would help the Cuban government in the event that Castro was gone, Bush responding that the US "would rejoice in being able to help a democratically elected government in Cuba" and his conviction that Cubans wanted the same form of democracy and freedom sought in Panama and Nicaragua as well as other countries in that hemisphere. After admitting he felt his comments would be ineffective, Bush said, "I would encourage Castro to move toward free and fair elections. I would encourage him to lighten up on the question of human rights, where he's been unwilling to even welcome the U.N. back to take a look again. And I am not going to change the policy of the United States Government towards Mr. Castro. We're going to continue to try to bring the truth to Cuba, just as we did to Czechoslovakia and Poland and other countries."[43]

In a May 21, 1991 radio address to mark the 89th anniversary of Cuban independence, Bush requested "Fidel Castro to free political prisoners in Cuba and allow the United Nations Commission on Human Rights to investigate possible human rights violations in Cuba".[44] In September, Gorbachev announced the Soviet Union's intent to withdraw troops from Cuba.[45] Shortly thereafter, the Bush administration stated the possibility of the move weakening Castro but officials confirmed the administration's reluctance to become involved in hastening his fall, citing the chances of either turning Cuba into a sour spot in relations between the US and the Soviet Union or action on the part of America antagonizing Latin American allies of the administration.[46] In April 1992 Bush tightened the long-standing embargo against trade with Cuba.[47] On December 31, 1992, the US federal government released forty-five Cubans that had defected to the US through an airliner. The Cuban government had beforehand accused the US of violating international law with its policy of granting political asylum to Cubans.[48]

Honduras

In March. 1989, the US requested Honduras to allow Nicaraguan guerrillas to remain in their territory for another year. The plea was made by Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs Robert M. Kimmitt during his meeting in Honduras with President José Azcona del Hoyo, concurrently with Honduras officials meeting contra leaders for a discussion on plans to disarm the rebels.[49]

On April 17, 1990, Bush met with Honduras President Rafael Callejas at the White House for a wide-ranging discussion that included their shared satisfaction with the stability of the relationship between the US and Honduras. Bush praised Honduras for its "productive role in achieving a multilateral agreement on the peaceful demobilization and repatriation of the Nicaraguan resistance in conditions of safety for all concerned" and indicated American support for this policy. Bush also pledged American aid "to ensure humanitarian assistance to those in need in both Nicaragua and Honduras as they return to their homes, their families, and their jobs, and play a vital role in helping Nicaragua establish lasting democratic institutions."[50]

Nicaragua

The ending of the Cold War left Nicaragua without strong Soviet support. By December 1989, President-elect Bush indicated his support for approaching the Nicaraguan government with pressure on moving it toward a democracy while avoiding an early confrontation with Congress over aid to the Nicaraguan Contra rebels.[51] With the help of Costa Rican President Óscar Arias, the Bush administration restored full diplomatic recognition and negotiated the free elections that brought democratic forces to power in Managua. He then sought large sums of U.S. aid from Congress.[52]

Venezuela

On March 4, 1989, government and banking officials announced the intent of the Bush administration to transfer nearly 2 billion in emergency loans to Venezuela to aid the country amid rioting and murders in Caracas during an economic crisis. Economists and congressional Democrats contended that the Venezuelan events were reflective of the futility of the lending in return for attempts by the debtor nations to overhaul their inflation-wracked economies imposed by the Treasury Department under the leadership of James Baker.[53]

On May 3, 1991, Bush met with President Carlos Andres Perez during a private visit by Perez to the US. The two leaders discussed the El Salvador peace process and their shared satisfaction with the agreement between the El Salvador government and the guerillas the previous week. Bush praised Perez for being part of the peace process in El Salvador and the two also talked about Nicaragua, Haiti democracy, and international oil issues.[54]

Panama: Operation Just Cause

In Panama, soldiers and police under orders of dictator Manuel Noriega killed an American Marine. Bush had enough. From the White House point of view The attacks brought a festering issue to a climax:

- Noriega had long been an American ally in Cold War Latin America. Essentially a paid anti-communist in the region, Noriega was a drug trafficker and tyrant who had become more trouble than he was worth. He stole a presidential election, continued to be a center for destabilizing drug running and money-laundering, and his erratic behavior raised concerns about the fate of the Panama Canal.[55]

Bush ordered Operation Just Cause in December 1989, an invasion that was the largest projection of American military power since Vietnam. American forces quickly depose Noriega, who was brought to the United States for trial and imprisonment on narcotics charges.[56]

In January 1990, Bush announced an economic recovery plan for Panama that included the implementing of loans, guarantees, and export opportunities to aid Panama's private sector as well as create jobs and an assistance package intended to balance payment support, public investment and restructuring along with attempting to normalize relations between Panama and the international financial institutions.[57]

The invasion of Panama was criticized on December 22, 1989 when Algeria, Colombia, Nepal, Senegal, and Yugoslavia filed a draft resolution to the United Nation Security Council.[58] They wanted a resolution that “strongly deplores the intervention in Panama...which constitutes a flagrant violation of international law and of the independence, sovereignty and territorial integrity of States”.[59] The draft also requested the immediate withdrawal of troops and end to the conflict. The resolution was vetoed. However, on December 29, 1989, the United Nations General Assembly held an emergency session called by Cuba and Nicaragua.[60] It resulted in a 75–20 vote condemning the action of the United States and those taken by Bush.[59][61] It also called for a halt of the invasion and a withdrawal of troops.[60] During the assembly, USSR ambassador Alexander M. Belonogov said that “the armed act of U.S. aggression against Panama is a challenge to the international community.”[59]

Asia

China

Following China's violent suppression of the pro-democracy Tiananmen Square protests of June 1989, Washington and other governments enacted a number of measures against China's violation of human rights. The US suspended high-level official exchanges with the PRC and weapons exports from the US to the PRC. The US also imposed small-scale economic sanctions. In the summer of 1990, at the G7 Houston summit, the West called for renewed political and economic reforms in mainland China, particularly in the field of human rights.[62]

Bush reacted in moderate fashion trying to avoid a major break.[63] At a news conference on January 24, 1990, Bush was asked about his intent to play China against the Soviet Union in the event that Gorbachev fall from power and his successor is in the harsh mold of dictator Joseph Stalin. Bush called China "a key player" in world events and cited its importance in geopolitics for why he would want the US to have either good or improved relations in spite of admitting the current circumstance was "unsatisfactory conditions".[64] Bush also decided that Tiananmen should not interrupt Sino-U.S. relations. He secretly sent special envoy Brent Scowcroft to Beijing to meet with Deng Xiaoping, and, the economic sanctions that had been levied against China were lifted.[65] George Washington University revealed that, through high-level secret channels on 30 June 1989, the US government conveyed to the government of the People's Republic of China that the events around the Tiananmen Square protests were an "internal affair".[66] Fang Lizhi and his wife remained in the US Embassy until 25 June 1990, when they were allowed to go into exile in Britain.[67]

Trade sanctions

Sino-US military ties and arms sales were abruptly terminated in 1989 and as of 2019 have never been restored. In an April 30, 1991 statement, Press Secretary Fitzwater announced that Bush had "decided not to approve a request to license the export of U.S. satellite components to China for a Chinese domestic communications satellite", citing Chinese companies engaging in activities that raised proliferation concerns for the administration and that Bush's decision underscored the US taking nonproliferation seriously. Fitzwater furthered that the US was having ongoing discussions with China aimed at getting China to align with international guidelines on missiles and technology exports related to them.[68] The following month, on May 14, Bush announced the nomination of J. Stapleton Roy to succeed Lilley as US Ambassador to China.[69] Tiananmen event disrupted the US-China trade relationship, and US investors' interest in mainland China dropped dramatically. Tourist traffic fell off sharply.[70] The Bush administration denounced the repression and suspended certain trade and investment programs on June 5 and 20, 1989, however Congress was responsible for imposing many of these actions, and the White House itself took a far less critical attitude of Beijing, repeatedly expressing hope that the two countries could maintain normalized relations.[71] Some sanctions were legislated while others were executive actions. Examples include:

- The US Trade and Development Agency (TDA): new activities in mainland China were suspended from June 1989 until January 2001, when President Bill Clinton lifted this suspension.

- Overseas Private Insurance Corporation (OPIC): new activities have been suspended since June 1989.

- Development Bank Lending/International Monetary Fund (IMF) Credits: the United States does not support development bank lending and will not support IMF credits to the PRC except for projects that address basic human needs.

- Munitions List Exports: subject to certain exceptions, no licenses may be issued for the export of any defense article on the US Munitions List. This restriction may be waived upon a presidential national interest determination.

- Arms Imports – import of defense articles from the PRC was banned after the imposition of the ban on arms exports to the PRC. The import ban was subsequently waived by the Administration and reimposed on May 26, 1994. It covers all items on the BATFE's Munitions Import List. During this critical period, J. Stapleton Roy, a career US Foreign Service Officer, served as ambassador to Beijing.[72]

After Tiananmen Square, Sino-US relations deteriorated sharply, falling to their worst since the 1960s. Beijing since the 1950s had feared an American "conspiracy to subvert Chinese socialism".[73] The period 1989 to 1992 also witnessed a revival of hard-line Maoist ideologies and increased paranoia by the PRC as communist regimes collapsed in Eastern Europe. Nonetheless, China continued to seek foreign business and investment.

India

India and the U.S. squabbled over technicalities in trade arrangements. In the first months of the Bush administration, the US pressed for India to enforce stronger patent protection laws or be subject to retaliatory trade measures. American and Indian officials discussed the matter in March during a Washington visit. The subject was seen as threatening to a joint scientific program involving the US and India.[74] In May 1989, responding to the US placing India on a list of countries that were unfair traders, Commerce Minister Dinesh Singh charged the US with being in violation with the agreements it agreed to under the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade and that India regarded "this law and action under it as totally unjustified, irrational and unfair."[75]

In May 1991, former Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi was assassinated by suicide bomber. Bush condemned the assassination as a "terrible tragedy" that would not undermine the function of democracy in India and said that it was "a time for calm, for peaceful resolution to differences", a concept he furthered was understood by Gandhi and his family.[76]

North Korea

Throughout 1989, the Bush administration conducted a quiet diplomatic effort to persuade North Korea to turn over its nuclear installations to international safeguards. On October 25 of that year, administration officials confirmed their concerns that North Korea was trying to develop nuclear weapons.[77]

During a January 6, 1992 news conference Bush held with South Korean President Roh Tae Woo, Woo told reporters that the two leaders had "jointly reaffirmed the unshakable position that North Korea must sign and ratify a nuclear safeguard agreement and that the recently initiated joint declaration for a nonnuclear peninsula must be put into force at the earliest possible date." Bush called for both North and South Korea to implement bilateral inspection arrangements under the joint nonnuclear declaration from the previous month and stated North Korea's obligation with these terms would result in the US and South Korea willfully forgoing the Team Spirit exercise that year. Roh said the US and South Korea would partner in efforts to end nuclear weapon development in North Korea and have the country abandon nuclear processing plants and reduce enrichment facilities.[78]

South Korea

In September 1989, Vice President Dan Quayle traveled to Seoul to meet with President of South Korea Roh Tae-woo, Quayle stating that the US was committed to South Korea's security and the US supported removing American military faculties from Seoul. Roh expressed satisfaction with the administration's insuring stability for Korea and aiding South Korea's development.[79]

On October 20, 1991, Bush administration officials announced their intention to withdraw American nuclear weapons from South Korea. The move was intended to convince North Korea to authorize international inspection of its own nuclear plants and partly was caused by American officials no longer considering the bombs necessary to defend South Korea.[80]

Japan

In its first months, the Bush administration negotiated with Japan to collaborate on a project that would produce a jet fighter. While supporters viewed the joint project as allowing the US access to Japanese technology and prevent Japan from constructing its own aircraft, the agreement attracted bipartisan criticism from members of Congress who believed the deal would give American technology to Japan and allow the country to form a major aeronautics industry.[81] Bush announced the completion of the deal on April 28, 1989,[82] assessing the aircraft as providing an improvement in the defense of both America and Japan.[83]

During a March 1, 1990 visit to the office of former President Reagan, Bush was asked about his upcoming meeting with Prime Minister Toshiki Kaifu, Bush answering that the meeting would be interesting given Kaifu had "just solidified his position in the party and he's been reanointed. And we've got to convince him that we've got to move forward with some of the tough problems, as you know."[84] On March 12, Bush met with former Prime Minister of Japan Noboru Takeshita for an hour to discuss shared economic issues and "the fact that their solution will require extraordinary efforts on both sides of the Pacific."[85] On April 28, Bush announced Japan was being removed from the list of countries the US was targeting with reprisal tariffs for what was considered unfair trading practices on the part of Japan. The decision came at the recommendation of U.S. Trade Representative Carla A. Hills and was hailed by Japanese officials. The move also came at a time where the US had a 50 billion trade deficit with Japan, and congressional critics said the choice was prior to the obtaining of verifiable results.[86] On July 28, Bush announced he would not block the sale of Semi-Gas Systems Inc. to Japan's Nippon Sanso. The Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States recommended Bush not interfere in the Nippon Sanso bid.[87]

In April 1991, Bush met with Prime Minister Kaifu, Bush stating afterward that the pair were "committed to see that that bashing doesn't go forward and that this relationship goes on." Bush confirmed the US would like access to the Japanese rice market and that Kaifu had explained the objections being raised in Japan, Bush furthering that a resolution to the issue could be reached under the General Agreement on tariffs and trade.[88] In November, during an address in New York, Bush stated that bashing Japan had become a regularity in parts of the US and had served to strain relations. Two days later, Chief Cabinet Secretary Koichi Kato said that Japan had mixed feelings toward the US and that Japan was appreciative by American efforts to reduce the US budget deficit.[89] On December 7, the fiftieth anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor, Bush accepted an apology from Japan over the event issued by Prime Minister Kiichi Miyazawa the previous day and urged progress be made in improving relations between the US and Japan.[90]

In January 1992, during a speech at Andrews Air Force Base, Bush stated his upcoming trip to Japan would produce American exports that would lead to more jobs. This portion of the speech "was quickly overshadowed by the Government's announcement that unemployment rose to 7.1 percent in December, the highest rate in six years." White House Chief of Staff Samuel K. Skinner replied to the release of the figures by saying they made the trip "more important than ever." Aboard Air Force One, Bush explained the positive of the trip would be securing a deal with Japan featuring the country pledging to buy an additional 10 billion in American auto parts each year until 1995 and that 200,000 jobs would be created over this period.[91]

Gulf Waredit

On August 2, 1990, Iraq, led by Saddam Hussein, invaded its oil-rich neighbor to the south, Kuwait. Early reports noted extensive casualties and Iraq warned against foreign intervention. National Security Advisor Brent Scowcroft was reported to have informed President Bush of the military action during the evening and State Department officials engaged in a late night discussion over the matter.[92] The following morning, President Bush reiterated American condemnation of Iraq and announced his directing of Tom Pickering to collaborate with Kuwait "in convening an emergency meeting of the Security Council" and his signing of Executive Orders "freezing Iraqi assets in this country and prohibiting transactions with Iraq" and "freezing Kuwaiti assets", the latter executive order being intended to prevent Iraq from interfering with Kuwait's assets during its occupation.[93] Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney traveled to Saudi Arabia to meet with King Fahd; Fahd requested US military aid in the matter, fearing a possible invasion of his country as well.[94] The request was met initially with Air Force fighter jets. Iraq made attempts to negotiate a deal that would allow the country to take control of half of Kuwait. Bush rejected this proposal and insisted on a complete withdrawal of Iraqi forces.[95] The planning of a ground operation by US-led coalition forces began forming in September 1990, headed by General Norman Schwarzkopf.[94]

Bush decided on war.[96] On September 11, 1990, Bush spoke before a joint session of the U.S. Congress regarding the authorization of air and land attacks, laying out four immediate objectives: "Iraq must withdraw from Kuwait completely, immediately, and without condition. Kuwait's legitimate government must be restored. The security and stability of the Persian Gulf must be assured. And American citizens abroad must be protected." He then outlined a fifth, long-term objective: "Out of these troubled times, our fifth objective – a new world order – can emerge: a new era – freer from the threat of terror, stronger in the pursuit of justice, and more secure in the quest for peace. An era in which the nations of the world, East and West, North and South, can prosper and live in harmony.... A world where the rule of law supplants the rule of the jungle. A world in which nations recognize the shared responsibility for freedom and justice. A world where the strong respect the rights of the weak."[97] With the United Nations Security Council opposed to Iraq's violence, Congress passed the Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Iraq Resolution of 1991 signed by President Bush on January 14, 1991[94] with a set goal of returning control of Kuwait to the Kuwaiti government, and protecting America's interests abroad.[95]

On January 16, 1991, Bush addressed the nation from the Oval Office, announcing that "allied air forces began an attack on military targets in Iraq and Kuwait. These attacks continue as I speak".[98]

Early on the morning of January 17, 1991, Coalition forces launched the first attack, which included more than 4,000 bombing runs by coalition aircraft.[99] This pace would continue for the next four weeks, until a ground invasion was launched on February 24, 1991. Coalition forces penetrated Iraqi lines and pushed toward Kuwait City while on the west side of the country, forces were intercepting the retreating Iraqi army. Bush made the decision to stop the offensive after a mere 100 hours.[100][101] Critics labeled this decision premature, as hundreds of Iraqi forces were able to escape; Bush responded by saying that he wanted to minimize U.S. casualties. Opponents further charged that Bush should have continued the attack, pushing Hussein's army back to Baghdad, then removing him from power.[95] Bush explained that he did not give the order to overthrow the Iraqi government because it would have "incurred incalculable human and political costs.... We would have been forced to occupy Baghdad and, in effect, rule Iraq."[102]

Bush's approval ratings skyrocketed after the successful offensive.[95] Additionally, President Bush and Secretary of State Baker felt the coalition victory had increased U.S. prestige abroad and believed there was a window of opportunity to use the political capital generated by the coalition victory to revitalize the Arab-Israeli peace process. The administration immediately returned to Arab-Israeli peacemaking following the end of the Gulf War; this resulted in the Madrid Conference, later in 1991.[103]

Soviet Unionedit

1989edit

In January 1989, Brent Scowcroft voiced his belief that the Cold War had not concluded and Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev was attempting to cause issues for the Western alliance. When asked about these comments during his first news conference in office a week later on January 27, Bush said of the administration's position on the Soviet Union, "Let's take our time now. Let's take a look at where we stand on our strategic arms talks; on conventional force talks; on chemical, biological weapons talks; on some of our bilateral policy problems with the Soviet Union; formulate the policy and then get out front -- here's the U.S. position."[12] When asked about the possibility of superpower deals being offered to the US on February 6, Bush said he was unsure but spoke of the influence the Soviet Union could have on the administration's willingness to engage Central America: "I can see a possibility of cooperation in Central America because I would like the Soviets to understand that we have very special interests in this hemisphere, particularly in Central America, and that our commitment to democracy and to freedom and free elections and these principles is unshakeable."[104] On February 9, during an address to a joint session of Congress, Bush called for change in the world and singled out the Soviet Union as an area he wished to improve relations with, citing "fundamental facts remain that the Soviets retain a very powerful military machine in the service of objectives which are still too often in conflict with ours" and that he had personally assured Gorbachev that the US would be ready to move forward after reviewing its policies there.[105] In a speech at the Annual Conference of the Veterans of Foreign Wars on March 6, Bush addressed "the key issue of change within the Soviet Union" where more questions lingered than answers and offered a position the federal government could deploy amid uncertainty over the Soviet Union's future: "We should press for progress that contributes to a more stable relationship between the United States and the Soviet Union, but we must combine our readiness to build better relations with a resolve to maintain defenses adequate to secure our interests."[106]

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Foreign_policy_of_the_George_H._W._Bush_administration

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk