A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Part of a series on |

| History of the Cold War |

|---|

|

The Cold War (1953–1962) discusses the period within the Cold War from the end of the Korean War in 1953 to the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962. Following the death of Joseph Stalin earlier in 1953, new leaders attempted to "de-Stalinize" the Soviet Union causing unrest in the Eastern Bloc and members of the Warsaw Pact.[1] In spite of this there was a calming of international tensions, the evidence of which can be seen in the signing of the Austrian State Treaty reuniting Austria, and the Geneva Accords ending fighting in Indochina. However, this period of good happenings was only partial with an expensive arms race continuing during the period and a less alarming, but very expensive space race occurring between the two superpowers as well. The addition of African countries to the stage of cold war, such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo joining the Soviets, caused even more unrest in the West.[2]

Eisenhower and Khrushchev

When Harry S. Truman was succeeded in office by Dwight D. Eisenhower as the 34th U.S. President in 1953, the Democrats lost their two-decades-long control of the U.S. presidency. Under Eisenhower, however, the United States' Cold War policy remained essentially unchanged. Whilst a thorough rethinking of foreign policy was launched (known as "Project Solarium"), the majority of emerging ideas (such as a "rollback of communism" and the liberation of Eastern Europe) were quickly regarded as unworkable. An underlying focus on the containment of Soviet communism remained to inform the broad approach of U.S. foreign policy.

While the transition from the Truman to the Eisenhower presidencies was a mild transition in character (from moderate to conservative), the change in the Soviet Union was immense. With the death of Joseph Stalin (who led the Soviet Union from 1928 and through the Great Patriotic War) in 1953, Georgy Malenkov was named leader of the Soviet Union. This was short lived however, as Nikita Khrushchev soon undercut all of Malenkov's authority as First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and took control of the Soviet Union himself. Malenkov joined a failed coup against Khrushchev in 1957, after which he was sent to Kazakhstan.

During a subsequent period of collective leadership, Khrushchev gradually consolidated his hold on power. At a speech[3] to the closed session of the Twentieth Party Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, February 25, 1956, First Secretary Nikita Khrushchev shocked his listeners by denouncing Stalin's personality cult and the many crimes that occurred under Stalin's leadership. Although the contents of the speech were secret, it was leaked to outsiders, thus shocking both Soviet allies and Western observers. Khrushchev was later named premier of the Soviet Union in March 1958.

The effect of this speech on Soviet politics was immense. With it Khrushchev stripped his remaining Stalinist rivals of their legitimacy in a single stroke, dramatically boosting the First Party Secretary's domestic power. Khrushchev followed by easing restrictions, freeing some dissidents and initiating economic policies that emphasized commercial goods rather than just coal and steel production.

U.S. strategy: "massive retaliation" and "brinksmanship"

Conflicting objectives

When Eisenhower entered office in 1953, he was committed to two possibly contradictory goals: maintaining—or even heightening—the national commitment to counter the spread of Soviet influence; and satisfying demands to balance the budget, lower taxes, and curb inflation. The most prominent of the doctrines to emerge from this goal was "massive retaliation", which Secretary of State John Foster Dulles announced early in 1954. Eschewing the costly, conventional ground forces of the Truman administration, and wielding the vast superiority of the U.S. nuclear arsenal and covert intelligence, Dulles defined this approach as "brinksmanship" in a January 16, 1956, interview with Life: pushing the Soviet Union to the brink of war in order to exact concessions.

Eisenhower inherited from the Truman administration a military budget of roughly US$42 billion, as well as a paper (NSC-141) drafted by Acheson, Harriman, and Lovett calling for an additional $7–9 billion in military spending.[4] With Treasury Secretary George Humphrey leading the way, and reinforced by pressure from Senator Robert A. Taft and the cost-cutting mood of the Republican Congress, the target for the new fiscal year (to take effect on July 1, 1954) was reduced to $36 billion. While the Korean armistice was on the verge of producing significant savings in troop deployment and money, the State and Defense Departments were still in an atmosphere of rising expectations for budgetary increases. Humphrey wanted a balanced budget and a tax cut in February 1955, and had a savings target of $12 billion (obtaining half of this from cuts in military expenditures).

Although unwilling to cut deeply into defense, the President also wanted a balanced budget and smaller defense allocations. "Unless we can put things in the hands of people who are starving to death we can never lick communism", he told his cabinet. With this in mind, Eisenhower continued funding for America's innovative cultural diplomacy initiatives throughout Europe which included goodwill performances by the "soldier-musician ambassadors" of the Seventh Army Symphony Orchestra.[5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13] Moreover, Eisenhower feared that a bloated "military–industrial complex" (a term he popularized) "would either drive U.S. to war—or into some form of dictatorial government" and perhaps even force the U.S. to "initiate war at the most propitious moment." On one occasion, the former commander of the greatest amphibious invasion force in history privately exclaimed, "God help the nation when it has a President who doesn't know as much about the military as I do."[14]

In the meantime, however, attention was being diverted elsewhere in Asia. The continuing pressure from the "China lobby" or "Asia firsters", who had insisted on active efforts to restore Chiang Kai-shek to power was still a strong domestic influence on foreign policy. In April 1953 Senator Robert A. Taft and other powerful Congressional Republicans suddenly called for the immediate replacement of the top chiefs of the Pentagon, particularly the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Omar Bradley. To the so-called "China lobby" and Taft, Bradley was seen as having leanings toward a Europe-first orientation, meaning that he would be a possible barrier to new departures in military policy that they favored. Another factor was the vitriolic accusations of McCarthyism, where large portions of the U.S. government allegedly contained covert communist agents or sympathizers. But after the mid-term elections in 1954–and censure by the Senate–the influence of Joseph McCarthy ebbed after his unpopular accusations against the Army.

Eisenhower administration strategy

I think most of our people cannot understand that we are actually at war. They need to hear shells. They are not psychologically prepared for the concept that you can have a war when you don't have actual fighting.

— Admiral Hyman G. Rickover addressing U.S. Senate Committee on Defense Preparedness on January 6, 1958[15]

The administration attempted to reconcile the conflicting pressures from the "Asia firsters" and pressures to cut federal spending while continuing to fight the Cold War effectively. On May 8, 1953, the President and his top advisors tackled this problem in "Operation Solarium", named after the White House sunroom where the president conducted secret discussions. Although it was not traditional to ask military men to consider factors outside their professional discipline, the President instructed the group to strike a proper balance between his goals to cut government spending and an ideal military posture.

The group weighed three policy options for the next year's military budget: the Truman-Acheson approach of containment and reliance on conventional forces; threatening to respond to limited Soviet "aggression" in one location with nuclear weapons; and serious "liberation" based on an economic response to the Soviet political-military-ideological challenge to Western hegemony: propaganda campaigns and psychological warfare. The third option was strongly rejected. Eisenhower and the group (consisting of Allen Dulles, Walter Bedell Smith, C.D. Jackson, and Robert Cutler) instead opted for a combination of the first two, one that confirmed the validity of containment, but with reliance on the American air-nuclear deterrent. This was geared toward avoiding costly and unpopular ground wars, such as Korea.

The Eisenhower administration viewed atomic weapons as an integral part of U.S. defense, hoping that they would bolster the relative capabilities of the U.S. vis-à-vis the Soviet Union. The administration also reserved the prospects of using them, in effect, as a weapon of first resort, hoping to gain the initiative while reducing costs. By wielding the nation's nuclear superiority, the new Eisenhower-Dulles approach was a cheaper form of containment geared toward offering Americans "more bang for the buck".[citation needed]

Thus, the administration increased the number of nuclear warheads from 1,000 in 1953 to 18,000 by early 1961. Despite overwhelming U.S. superiority, one additional nuclear weapon was produced each day. The administration also exploited new technology. In 1955 the eight-engined B-52 Stratofortress bomber, the first true jet bomber designed to carry nuclear weapons, was developed.

In 1961, the U.S. deployed 15 Jupiter IRBMs (intermediate-range ballistic missiles) at İzmir, Turkey, aimed at the western USSR's cities, including Moscow. Given its 1,500-mile (2,410 km) range, Moscow was only 16 minutes away. The U.S. could also launch 1,000-mile (1,600 km)-range Polaris SLBMs from submerged submarines.[16]

In 1962, the United States had more than eight times as many bombs and missile warheads as the USSR: 27,297 to 3,332.[17]

During the Cuban Missile Crisis the U.S. had 142 Atlas and 62 Titan I ICBMs, mostly in hardened underground silos.[16]

Fear of Soviet influence and nationalism

Allen Dulles, along with most U.S. foreign policy-makers of the era, considered many Third World nationalists and "revolutionaries" as being essentially under the influence, if not control, of the Warsaw Pact. Ironically, in War, Peace, and Change (1939), he had called Mao Zedong an "agrarian reformer", and during World War II he had deemed Mao's followers "the so called 'Red Army faction'".[18] But he no longer recognized indigenous roots in the Chinese Communist Party by 1950. In War or Peace, an influential work denouncing the containment policies of the Truman administration, and espousing an active program of "liberation", he writes:

Thus the 450,000,000 people in China have fallen under leadership that is violently anti-American, and takes its inspiration and guidance from Moscow... Soviet Communist leadership has won a victory in China which surpassed what Japan was seeking and we risked war to avert.[19]

Behind the scenes, Dulles could explain his policies in terms of geopolitics. But publicly, he used the moral and religious reasons that he believed Americans preferred to hear, even though he was often criticized by observers at home and overseas for his strong language.

Two of the leading figures of the interwar and early Cold War period who viewed international relations from a "realist" perspective, diplomat George Kennan and theologian Reinhold Niebuhr, were troubled by Dulles' moralism and the method by which he analyzed Soviet behavior. Kennan disagreed with the notion that the Soviets even had a world design after Stalin's death, being far more concerned with maintaining control of their own bloc. However, the underlying assumptions of a monolithic world communism, directed from the Kremlin, of the Truman-Acheson containment after the drafting of NSC-68[20] were essentially compatible with those of the Eisenhower-Dulles foreign policy. The conclusions of Paul Nitze's National Security Council policy paper were as follows:

What is new, what makes the continuing crisis, is the polarization of power which inescapably confronts the slave society with the free... the Soviet Union, unlike previous aspirants to hegemony, is animated by a new fanatic faith, antithetical to our own, and seeks to impose its absolute authority... the Soviet Union and second in the area now under control... In the minds of the Soviet leaders, however, achievement of this design requires the dynamic extension of their authority... To that end Soviet efforts are now directed toward the domination of the Eurasian land mass.[21]

The end of the Korean War

Prior to his election in 1953, Dwight D. Eisenhower was already displeased with the manner that Harry S. Truman had handled the war in Korea. After the United States secured a resolution from the United Nations to engage in military defense on behalf of South Korea led by the president Syngman Rhee, who had been invaded by North Korea in an attempt to unify all of Korea under the communist North Korean regime led by the dictator Kim Il-sung. President Truman engaged U.S. land, air, and sea forces;[22] United States involvement in the war quickly reversed the direction of military advancement into South Korea to military advancement into North Korea; to the point that North Korean forces were being forced against the border with China, which led to the involvement of hundreds of thousands of communist Chinese troops heavily assaulting U.S. and South Korean forces.[23] Acting on a campaign pledge made during his United States presidential election campaign, Eisenhower visited Korea on December 2, 1952, to assess to the situation. Eisenhower's investigation consisted of meeting with South Korean troops, commanders, and government officials, after his meetings Eisenhower concluded, "we could not stand forever on a static front and continue to accept casualties without any visible results. Small attacks on small hills would not end this war".[22] Eisenhower urged the South Korean President Syngman Rhee to compromise in order to speed up peace talks. This, coupled with the United States' threat of using nuclear weapons if the war did not end soon, led to the signing of an armistice on July 27, 1953. The armistice concluded the United States' initial Cold War concept of "limited war".[23] Prisoners of war were allowed to choose where they would stay, either the area that would become North Korea or the area to become South Korea, and a border was placed between the two territories in addition to an allotted demilitarized zone.[24][25] The "police action" implemented by the Korean U.N. agreement prevented communism from spreading from North Korea to South Korea. United States involvement in the Korean War demonstrated its readiness to the world to rally to the aid of nations under invasion, particularly communistic invasion, and resulted in President Eisenhower's empowered image as an effective leader against tyranny; this ultimately led to a strengthened position of the United States in Europe and guided the development of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization.[22] The primary effect of these developments for the United States were the military buildup called for in response to Cold War concerns as seen in NSC 68.

Origins of the Space Race

The Space Race between the United States and the Soviet Union was an integral component of the Cold War. Contrary to the Nuclear arms race, it was a peaceful competition in which the two powers could demonstrate their technological and theoretical advancements over the other. The Soviet Union was the first nation to enter the space realm with their launch of Sputnik 1 on October 4, 1957. The satellite was merely an 83.6-kilogram aluminum alloy sphere, which was a major downsize from the original 1,000-kilogram design, that carried a radio and four antennas into space. This size was shocking to western scientists as America was designing a much smaller 8-kilogram satellite. This size discrepancy was apparent due to the gap in weapon technology as the United States was able to develop much smaller nuclear warheads than their Soviet counterparts.[26] The Soviet Union later launched Sputnik 2 less than a month later.[27] The Soviet's satellite success caused a stir in America as people question why the United States had fallen behind the Soviet Union and if they could launch nuclear missiles at large American cities i.e. Chicago, Seattle, and Atlanta. President Dwight D. Eisenhower responded by creating the President's Science Advisory Committee (PSAC). This committee was appointed to lead the United States in policy for scientific and defense strategies.[28] Another United States response to the Soviets' successful satellite mission was a Navy led attempt to launch the first American satellite into space using its Vanguard TV3 missile.[29] This effort resulted in complete failure however, with the missile exploding on the launch pad. These developments resulted in a media frenzy, a frustrated and perplexed American public, and a struggle between the United States Army and Navy for control of the efforts to launch an American satellite into space. To resolve this, President Dwight D. Eisenhower appointed his President's Science Advisor, James Rhyne Killian, to consult with the PSAC to develop a solution.[29]

Creation of NASA

In reaction to the launch of Sputnik 1 by the Soviet Union, the President's Science Advisory Committee advised President Dwight D. Eisenhower to convert National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics into a new organization that would be more progressive in the United States' efforts for space exploration and research.[27] This organization was to be named the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). This agency would effectively shift the control of space research and travel from the military into the hands of NASA, which was to be a civilian-government administration.[29] NASA was to be in charge of all non-military space activity, while another organization (DARPA) was to be responsible for space travel and technology intended for military use.[30]

On April 2, 1958, Eisenhower presented legislation to Congress to implement the creation of the National Aeronautics and Space Agency. Congress responded by supplementing the creation of NASA, with an additional committee to be called the National Aeronautics and Space Council (NASC). The NASC would include the Secretary of State, the Secretary of Defense, the head of the Atomic Energy Commission, and the administrator of NASA. Legislation was passed by Congress, and then signed by President Eisenhower on July 29, 1958. NASA began operations on October 1, 1958.[29]

Kennedy's space administration

Since the conception of NASA, there had been considerations about the possibility of flying a man to the Moon. On July 5, 1961, the "Research Steering Committee on Manned Spaceflight", led by George Low presented the concept of the Apollo program to the NASA "Space Exploration Council". Although under the Dwight D. Eisenhower presidential administration NASA was given very little authority to further explore space travel, it was proposed that after the crewed Earth-orbiting missions, Project Mercury, that the government-civilian administration should make efforts to successfully complete a crewed lunar spaceflight mission. NASA administrator T. Keith Glennan explained that President Dwight D. Eisenhower, restricted any further space exploration beyond Project Mercury. After John F. Kennedy had been elected as president the previous November, policy for space exploration underwent a revolutionary change.[29]

"This nation should commit itself to the achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to Earth" -John F. Kennedy[31]

After President John F. Kennedy made this proposal to Congress on May 25, 1961, he remained true to this commitment to send a crewed lunar spaceflight in the ensuing 30 months prior to his assassination. Directly after his proposal, there was an 89% increase in government funding for NASA, followed by a 101% increase in funding the subsequent year.[31] This marked the beginning of the United States' mission to the Moon.

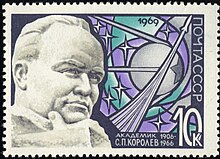

The Soviet Union in the Space Race

In August 1957 the Soviet Union tested the world's first successful Intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM), the R7 Semyorka. Within only two months of the launch of the Semyorka, Sputnik 1 became the first human made object in Earth's orbit.[32] This was followed by the launch of Sputnik II which carried Laika the first living space traveler though she did not survive the trip. This led to the creation of the Vostok programme in 1960 and the first living creatures to survive the trip to space, Belka and Strelka the Soviet space dogs. The Vostok Program was responsible for placing the first human in space, yet another task that the Soviet Union would complete before the United States.

The R7 ICBM

Prior to the start of the space race, the Soviet Union and the United States were struggling to build and obtain a missile that could not only carry nuclear cargo, but could also travel effectively from one country to another. These missiles, also known as ICBMs or Intercontinental Ballistic Missile, were key for either country to gain a major strategical advantage in the early years of the Cold War. However, where the U.S. failed in their initial ICBM flight tests, the Soviets proved to be years ahead in ICBM technology with their R7 program. The R7 missile, first tested in October 1953, originally was designed to carry a nose cone plus nuclear cargo equal to 3 tons, maintain a flight range of 7000 to 8000 km, a launch weight of 170 tons, and a two-stage launch and flight system.[33] However, during the initial testing, the R7 ICBM proved too small for the required cargo and major changes were approved and implemented in May 1954. These changes consisted of a heavier nose that could carry 3 tons of nuclear payload and a design change that would allow for a controlled take off and flight due to the new launch weight being 280 tons. This rocket proved effective in testing in May 1957 and was then slightly adjusted to support space flight.[34]

Sputnik 1 and Sputnik 2

On October 4, 1957, the Soviet Union successfully launched the first Earth satellite into space. Sputnik 1's official mission was to send back data from space, however the effects of this launch were monumental for both the USSR and the United States. For both countries, the launch of Sputnik 1 sparked the start of the Timeline of the Space Race. It created a curiosity for space flight and a relatively peaceful competition to the Moon. However the initial effects of Sputnik 1 for the United States was not a matter of exploration, but a matter of national security. What the USSR proved to the world, and mainly the United States, was that they were capable of launching a missile into space and potentially an ICBM carrying nuclear cargo at the United States. The fear of the unknown capability of Sputnik sparked fear in the Americans and many government officials went on record giving their thoughts on the matter. Senator Jackson of Seattle said the launch of Sputnik "was a devastating blow", and that " Eisenhower should declare a week of shame and danger".[35] For the Russians' the launch of Sputnik 1 proved to be a major advantage in the Cold War, because it secured their current leading position in the war, created a retaliation force in the event of a U.S. nuclear strike, and allowed for a competitive advantage in ICBM technology.

Sputnik 2 launched almost a month later on November 3, 1957, with a mission goal of carrying the first dog, Laika, into Earth orbit. This mission, though unsuccessful in the sense that Laika did not survive the mission, further established the USSR's position in the Cold War. Not only were the Soviets capable of launching a missile into space, but they could continue to complete successful space launches before the United States could complete one launch.

Lunar missions

The USSR launched three Lunar missions in 1959. The Lunar missions were the Russian equivalent to the United States Project Mercury and Project Gemini space programs, whose primary mission was to prepare to put the first human on the Moon.[36] The first of the Lunar missions was Luna 1, which launched on January 2, 1959. Its successful mission established the first rocket engine restart within Earth orbit and the first man-made object to establish heliocentric orbit. Luna 2, which launched on September 14, 1959, established the first impact into another celestial body (the Moon). Finally, Luna 3 launched on October 7, 1959, and took the first pictures of the dark side of the Moon. After these three missions in 1959, the Soviets continued their exploration of the Moon and its environment in 21 other Luna missions.[36]

Soviet space travel from 1960–1962

The Luna ("Moon") program was a giant step forward for the Soviets in achieving the goal of putting the first man on the Moon. It also "planted the building blocks" of a program for the Soviets to "sustain human beings safely and productively in low Earth orbit" with the creation of the Soviet "equivalent to the Apollo command module, the Soyuz space capsule".[36]

Over this two-year period, the Soviets were taking major steps forward in getting to the Moon with one mission set back, Sputnik 4. This mission was launched officially as a test of life support systems for future cosmonauts on May 15, 1960. However, on May 19, "an attempt to deorbit a space cabin failed" and sent the cabin into high Earth orbit, only for it to crash into the Earth in September of the same year.[37] The Soviets continued their space program, however by launching Sputnik 5 on August 19, 1960, which carried the first animals and plants to space and return them safely to Earth.

Other notable launches include:

- Vostok 1: Launched on April 12, 1961. Successfully carried the first human into space and orbit, Yuri Gagarin.

- Vostok 2: Launched August 6, 1961. Successfully carried the first crewed mission lasting one day carrying Gherman Titov.

- Vostok 3 and Vostok 4: Launched August 12, 1962. Vostok 3 carried Andriyan Nikolayev and Vostok 4 carried Pavel Popovich. Successfully completed the first dual crewed space flight, the first ship-to-ship radio contact and first simultaneous flight of crewed spacecraft.

The race continues

The Soviet Union continued to extend its lead in the space race with its mission on April 12, 1961, which made Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin the first human being to leave Earth's atmosphere and enter space. The United States gained some ground a month later, on May 5, 1961, when they sent Alan Shepard on a fifteen-minute flight outside of Earth's atmosphere during the Freedom 7 project. Unlike Gagarin, Shepard manually controlled his spacecraft's attitude and landed inside it thus technically making Freedom 7 the first “completed” human spaceflight by then FAI definitions. Prior to that on January 31, through NASA's Mercury-Redstone 2 mission, the chimpanzee Ham became the first Hominidae in space.[38]

On February 20, 1962, America made further progress as John Glenn became the first American to orbit the Earth in his Mercury mission Friendship 7.

Soviet strategy

In 1960 and 1961, Khrushchev tried to impose the concept of nuclear deterrence on the military. Nuclear deterrence holds that the reason for having nuclear weapons is to discourage their use by a potential enemy, with each side deterred from war because of the threat of its escalation into a nuclear conflict, Khrushchev believed, "peaceful coexistence" with capitalism would become permanent and allow the inherent superiority of socialism to emerge in economic and cultural competition with the West.

Khrushchev hoped that exclusive reliance on the nuclear firepower of the newly created Strategic Rocket Forces would remove the need for increased defense expenditures. He also sought to use nuclear deterrence to justify his massive troop cuts; his downgrading of the Ground Forces, traditionally the "fighting arm" of the Soviet armed forces; and his plans to replace bombers with missiles and the surface fleet with nuclear missile submarines.[39] However, during the Cuban Missile Crisis the USSR had only four R-7 Semyorkas and a few R-16s intercontinental missiles deployed in vulnerable surface launchers.[16] In 1962 the Soviet submarine fleet had only 8 submarines with short range missiles, which could be launched only from submarines that surfaced and lost their hidden submerged status.

Khrushchev's attempt to introduce a nuclear 'doctrine of deterrence' into Soviet military thought failed. Discussion of nuclear war in the first authoritative Soviet monograph on strategy since the 1920s, Marshal Vasilii Sokolovskii's "Military Strategy" (published in 1962, 1963, and 1968) and in the 1968 edition of Marxism-Leninism on War and the Army, focused upon the use of nuclear weapons for fighting rather than for deterring a war. Should such a war break out, both sides would pursue the most decisive aims with the most forceful means and methods. Intercontinental ballistic missiles and aircraft would deliver massed nuclear strikes on the enemy's military and civilian objectives. The war would assume an unprecedented geographical scope, but Soviet military writers argued that the use of nuclear weapons in the initial period of the war would decide the course and outcome of the war as a whole. Both in doctrine and in strategy, the nuclear weapon reigned supreme.[39]

Mutual assured destruction

An important part of developing stability was based on the concept of Mutual assured destruction (MAD). While the Soviets acquired atomic weapons in 1949, it took years for them to reach parity with the United States. In the meantime, the Americans developed the hydrogen bomb, which the Soviets matched during the era of Khrushchev. New methods of delivery such as Submarine-launched ballistic missiles and Intercontinental ballistic missiles with MIRV warheads meant that both superpowers could easily devastate the other, even after attack by an enemy.

This fact often made leaders on both sides extremely reluctant to take risks, fearing that some small flare-up could ignite a war that would wipe out all of human civilization. Nonetheless, leaders of both nations pressed on with military and espionage plans to prevail over the other side. At the same time, different avenues were pursued to try to advance their causes; these began to encompass athletics (with the Olympics becoming a battleground between ideologies as well as athletes) and culture (with respective countries supporting pianists, chess players, and movie directors).

One of the most important forms of nonviolent competition was the space race. The Soviets jumped out to an early lead in 1957 with the launching of Sputnik, the first artificial satellite, followed by the first crewed flight. The success of the Soviet space program was a great shock to the United States, which had believed itself to be ahead technologically. The ability to launch objects into orbit was especially ominous because it showed Soviet missiles could target anywhere on the planet.

Soon the Americans had a space program of their own but remained behind the Soviets until the mid-1960s. American President John F. Kennedy launched an unprecedented effort, promising that by the end of the 1960s Americans would land a man on the Moon, which they did, thus beating the Soviets to one of the more important objectives in the space race.

Another alternative to outright battle was the shadow war that was taking place in the world of espionage. There was a series of shocking spy scandals in the west, most notably that involving the Cambridge Five. The Soviets had several high-profile defections to the west, such as the Petrov Affair. Funding for the KGB, CIA, MI6 and smaller organizations such as the Stasi increased greatly as their agents and influence spread around the world.

In 1957 the CIA started the program of reconnaissance flights over the USSR using Lockheed U-2 spy planes. When such a plane was brought down over the Soviet Union on May 1, 1960 (1960 U-2 incident) at first the United States government denied the plane's purpose and mission, but was forced to admit its role as a surveillance aircraft when the Soviet government revealed that it had captured the pilot, Gary Powers, alive and was in possession of its largely intact remains. Coming just over two weeks before a scheduled East-West Summit in Paris, the incident caused a collapse in the talks and a marked deterioration in relations.

Eastern Bloc events

As the Cold War became an accepted element of the international system, the battlegrounds of the earlier period began to stabilize. A de facto buffer zone between the two camps was set up in Central Europe. In the south, Yugoslavia became heavily allied with the other European communist states. Meanwhile, Austria had become neutral.

1953 East Germany uprising

Following large numbers of East Germans traveling west through the only "loophole" left in the Eastern Bloc emigration restrictions, the Berlin sector border,[40] the East German government then raised "norms"—the amount each worker was required to produce—by 10%.[40] This was an attempt to transform East Germany into a satellite state of the Soviet Union. Already disaffected East Germans, who could see the relative economic successes of West Germany within Berlin, became enraged,[40] provoking large street demonstrations and strikes.[41] Nearly a million Germans partook in the protests and riots that took place at this time. A major emergency was declared and the Soviet Army intervened.[41]

Creation of the Warsaw Pact

In 1955, the Warsaw Pact was formed partly in response to NATO's inclusion of West Germany and partly because the Soviets needed an excuse to retain Red Army units in potentially problematic Hungary.[42] For 35 years, the Pact perpetuated the Stalinist concept of Soviet national security based on imperial expansion and control over satellite regimes in Eastern Europe.[43] Through its institutional structures, the Pact also compensated in part for the absence of Joseph Stalin's personal leadership, which had manifested itself since his death in 1953.[43] While Europe remained a central concern for both sides throughout the Cold War, by the end of the 1950s the situation was frozen. Alliance obligations and the concentration of forces in the region meant that any incident could potentially lead to an all-out war, and both sides thus worked to maintain the status quo. Both the Warsaw Pact and NATO maintained large militaries and modern weapons to possibly defeat the other military alliance.

1956 Polish protestsedit

After the death of the Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, the communist regime in Poland relaxed some of its policies. This led to a desire within the Polish public for more radical reforms of this kind, though the majority of Polish officials did not share this desire and were hesitant to reform. This caused impatience among industrial workers who began to strike; demanding better wages, lower work quotas, and cheaper food. 30,000 demonstrators carried banners demanding "Bread and Freedom".[44] Władysław Gomułka headed up the protests as the new leader of the Polish Communist party.

In Poland, demonstrations by workers demanding better conditions began on June 28, 1956, at Poznań's Cegielski Factories and were met with violent repression after Soviet Officer Konstantin Rokossovsky ordered the military to suppress the uprising. A crowd of approximately 100,000 gathered in the city center near the UB secret police building. 400 tanks and 10,000 soldiers of the Polish Army under General Stanislav Poplavsky were ordered to suppress the demonstration and during the pacification fired at the protesting civilians. The death toll was placed between 57[45] and 78 people,[46][47] including 13-year-old Romek Strzałkowski. There were also hundreds of people who sustained a variety of injuries.

Hungarian Revolution of 1956edit

After Stalinist dictator Mátyás Rákosi was replaced by Imre Nagy following Stalin's death[48][failed verification] and Polish reformist Władysław Gomułka was able to enact some reformist requests,[49] large numbers of protesting Hungarians compiled a list of Demands of Hungarian Revolutionaries of 1956,[50] including free secret-ballot elections, independent tribunals, and inquiries into Stalin and Rákosi Hungarian activities. Under the orders of Soviet defense minister Georgy Zhukov, Soviet tanks entered Budapest.[51] Protester attacks at the Parliament forced the collapse of the government.[52]

The new government that came to power during the revolution formally disbanded the Hungarian secret police, declared its intention to withdraw from the Warsaw Pact and pledged to re-establish free elections. The Soviet Politburo thereafter moved to crush the revolution with a large Soviet force invading Budapest and other regions of the country.[53] Approximately 200,000 Hungarians fled Hungary,[54] some 26,000 Hungarians were put on trial by the new Soviet-installed János Kádár government and, of those, 13,000 were imprisoned.[55] Imre Nagy was executed, along with Pál Maléter and Miklós Gimes, after secret trials in June 1958. By January 1957, the Hungarian government had suppressed all public opposition. These Hungarian government's violent oppressive actions alienated many Western Marxists,[who?] yet strengthened communist control in all the European communist states, cultivating the perception that communism was both irreversible and monolithic.

1960 U-2 incidentedit

The United States sent pilot Francis Gary Powers in a U-2 spy plane on a mission over Russian airspace to accumulate intelligence on the Soviet Union on 1 May 1960. The spy plan had taken off from Peshawar, Pakistan. Eisenhower administration authorized multiple such flights into Russian airspace, however, this one increased the tension on American-Soviet relations. On this day, Powers' plane was shot down and recovered by the Soviet Union. President Eisenhower and the United States tried to claim the plane was only used for weather purposes. The incident occurred just weeks before the two countries were supposed to attend a summit along with France and Great Britain. Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev would not release any information about the plane or its pilot in the days leading up to the summit so that the United States would continue its "weather plane" lie, though eventually Eisenhower would be forced to admit that the CIA had been conducting such surveillance missions for years. This was because, at the summit, Khrushchev admitted that the Soviets had captured the pilot alive and recovered undamaged sections of the spy plane. He demanded that President Eisenhower apologize at the summit. Eisenhower did agree to bring the intelligence gathering excursions to an end but would not apologize for the incident. Upon Eisenhower's refusal to apologize, the summit came to an end as Khrushchev would no longer contribute to the discussion. One of Eisenhower's primary goals as president was to improve the American-Soviet relationship, however, this exchange proved to damage such relations. The summit was also an opportunity for the two leaders to finalize a limited nuclear test ban treaty, but this was no longer a possibility after the United States handling of the incident.[56] Khrushchev threatened to drop a nuclear bomb on Peshawar,[57] thus warning Pakistan that it had become a target of Soviet nuclear forces.[58]

Berlin Crisis of 1961edit

This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2010) |

The crucial sticking point was still Germany after the Allies merged their occupation zones to form the Federal Republic of Germany in 1949. In response Soviets declared their section, the German Democratic Republic, an independent nation. Neither side acknowledged the division, however, and on the surface both maintained a commitment to a united Germany under their respective governments.

Germany was an important issue because it was regarded as the power center of the continent, and both sides believed that it could be crucial to the world balance of power. While both might have preferred a united neutral Germany, the risks of it falling into the enemy's camp for either side were too high, and thus the temporary post-war occupation zones became permanent borders.

In November 1958, Soviet first secretary Khrushchev issued an ultimatum giving the Western powers six months to agree to withdraw from Berlin and make it a free, demilitarized city. At the end of that period, Khrushchev declared, the Soviet Union would turn over to East Germany complete control of all lines of communication with West Berlin; the western powers then would have access to West Berlin only by permission of the East German government. The United States, Britain, and France replied to this ultimatum by firmly asserting their determination to remain in West Berlin and to maintain their legal right of free access to that city.

In 1959, the Soviet Union withdrew its deadline and instead met with the Western powers in a Big Four foreign ministers' conference. Although the three-month-long sessions failed to reach any important agreements, they did open the door to further negotiations and led to Soviet leader Khrushchev's visit to the United States in September 1959. At the end of this visit, Khrushchev and President Eisenhower stated jointly that the most important issue in the world was general disarmament and that the problem of Berlin and "all outstanding international questions should be settled, not by the application of force, but by peaceful means through negotiations."

However, in June 1961 Soviet first secretary Khrushchev created a new crisis over the status of West Berlin when he again threatened to sign a separate peace treaty with East Germany, which he said, would end existing four-power agreements guaranteeing American, British, and French access rights to West Berlin. The three powers replied that no unilateral treaty could abrogate their responsibilities and rights in West Berlin, including the right of unobstructed access to the city.

As the confrontation over Berlin escalated, on 25 July President Kennedy requested an increase in the Army's total authorized strength from 875,000 to approximately 1 million men, along with an increase of 29,000 and 63,000 men in the active duty strength of the Navy and the Air Force. Additionally, he ordered that draft calls be doubled, and asked Congress for authority to order to active duty certain ready reserve units and individual reservists. He also requested new funds to identify and mark space in existing structures that could be used for fall-out shelters in case of attack, to stock those shelters with food, water, first-aid kits and other minimum essentials for survival, and to improve air-raid warning and fallout detection systems.

During the early months of 1961, the government actively sought a means of halting the emigration of its population to the West. By the early summer of 1961, East German President Walter Ulbricht apparently had persuaded the Soviets that an immediate solution was necessary and that the only way to stop the exodus was to use force. This presented a delicate problem for the Soviet Union because the four-power status of Berlin specified free travel between zones and specifically forbade the presence of German troops in Berlin.

During the spring and early summer, the East German regime procured and stockpiled building materials for the erection of the Berlin Wall. Although this extensive activity was widely known, few outside the small circle of Soviet and East German planners believed that East Germany would be sealed off.

On June 15, 1961, two months before the construction of the Berlin Wall started, First Secretary of the Socialist Unity Party and Staatsrat chairman Walter Ulbricht stated in an international press conference, "Niemand hat die Absicht, eine Mauer zu errichten!" (No one has the intention to erect a wall). It was the first time the colloquial term Mauer (wall) had been used in this context.

On Saturday, August 12, 1961, the leaders of East Germany attended a garden party at a government guesthouse in Döllnsee, in a wooded area to the north of East Berlin, and Walter Ulbricht signed the order to close the border and erect a Wall.

At midnight the army, police, and units of the East German army began to close the border and by morning on Sunday, August 13, 1961, the border to West Berlin had been shut. East German troops and workers had begun to tear up streets running alongside the barrier to make them impassable to most vehicles, and to install barbed wire entanglements and fences along the 156 km (97 mi) around the three western sectors and the 43 km (27 mi) which actually divided West and East Berlin. Approximately 32,000 combat and engineer troops were used in building the Wall. Once their efforts were completed, the Border Police assumed the functions of manning and improving the barrier. East German tanks and artillery were present to discourage interference by the West and presumably to assist in the event of large-scale riots.

On 30 August 1961, President John F. Kennedy ordered 148,000 Guardsmen and Reservists to active duty in response to East German moves to cut off allied access to Berlin. The Air Guard's share of that mobilization was 21,067 individuals. ANG units mobilized in October included 18 tactical fighter squadrons, 4 tactical reconnaissance squadrons, 6 air transport squadrons, and a tactical control group. On 1 November; the Air Force mobilized three more ANG fighter interceptor squadrons. In late October and early November, eight of the tactical fighter units flew to Europe with their 216 aircraft in operation "Stair Step", the largest jet deployment in the Air Guard's history. Because of their short range, 60 Air Guard F-104 interceptors were airlifted to Europe in late November. The United States Air Forces in Europe (USAFE) lacked spare parts needed for the ANG's aging F-84s and F-86s. Some units had been trained to deliver tactical nuclear weapons, not conventional bombs and bullets. They had to be retrained for conventional missions once they arrived on the continent. The majority of mobilized Air Guardsmen remained in the U.S.[59]

The four powers governing Berlin (France, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and the United States) had agreed at the 1945 Potsdam Conference that Allied personnel would not be stopped by East German police in any sector of Berlin. But on 22 October 1961, just two months after the construction of the Wall, the U.S. Chief of Mission in West Berlin, E. Allan Lightner, was stopped in his car (which had occupation forces license plates) while going to a theater in East Berlin. Army General Lucius D. Clay (retired), U.S. President John F. Kennedy's Special Advisor in West Berlin, decided to demonstrate American resolve.

The attempts of a U.S. diplomat to enter East Berlin were backed by U.S. troops. This led to the stand-off between US and Soviet tanks at Checkpoint Charlie on 27–28 October 1961. The stand-off was resolved only after direct talks between Ulbricht and Kennedy.

The Berlin Crisis saw US Army troops facing East German Army troops in a stand-off, until the East German government backed down. The crisis ended in the summer of 1962 and the personnel returned to the United States.[59]

During the crisis KGB prepared an elaborate subversion and disinformation plan "to create a situation in various areas of the world which would favor dispersion of attention and forces by the U.S. and their satellites, and would tie them down during the settlement of the question of a German peace treaty and West Berlin". On 1 August 1961 this plan was approved by CPSU Central Committee.[60]

Third World arena of conflictedit

The Korean War marked a shift in the focal point of the Cold War, from postwar Europe to East Asia. After this point, in the wake of the disintegration of Europe's colonial empires, proxy battles in the Third World became an important arena of superpower competition in the establishment of alliances and jockeying for influence in these emerging nations. Many Third World nations, however, did not want to align themselves with either of the superpowers. The Non-Aligned Movement, led by India, Egypt, and Yugoslavia, attempted to unite the third world against what was seen as imperialism by both the East and the West.

Defense pactsedit

The Eisenhower administration attempted to formalize its alliance system through a series of pacts. Its Southeast Asian allies were joined into the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO) while allies in Latin America were placed in the Inter-American Treaty of Reciprocal Assistance (TIAR). The ANZUS alliance was signed between the Australia, New Zealand, and the U.S. None of these groupings was as successful as NATO had been in Europe.

John Foster Dulles, a rigid anti-communist, focused aggressively on Third World politics. He intensified efforts to "integrate" the entire non-communist Third World into a system of mutual defense pacts, traveling almost 500,000 miles in order to cement new alliances. Dulles initiated the Manila Conference in 1954, which resulted in the SEATO pact that united eight nations (either located in Southeast Asia or with interests there) in a neutral defense pact. This treaty was followed in 1955 by the Middle East Treaty Organization (METO), uniting the United Kingdom, Turkey, Iraq, Iran, and Pakistan in a defense organization. A Northeast Asia Treaty Organization (NEATO) comprising the U.S., Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan was also considered.

Decolonizationedit

The combined effects of two great European wars had weakened the political and economic domination of Africa, Asia, Oceania, Latin America, and the Middle East by European powers. This led to a series of waves of African and Asian decolonization following World War II; a world that had been dominated for over a century by Western imperialist colonial powers was transformed into a world of emerging African, Middle Eastern, and Asian nations. The sheer number of nation states increased drastically.

The Cold War started placing immense pressure on developing nations to align with one of the superpower factions. Both promised substantial financial, military, and diplomatic aid in exchange for an alliance, in which issues like corruption and human rights abuses were overlooked or ignored. When an allied government was threatened, the superpowers were often prepared and willing to intervene.

In such an international setting, the Soviet Union propagated a role as the leader of the "anti-imperialist" camp, currying favor in the Third World as being a more staunch opponent of colonialism than many independent nations in Africa and Asia. Khrushchev broadened Moscow's policy by establishing new relations with India and other key non-aligned, non-communist states throughout the Third World. Many countries in the emerging Non-Aligned Movement developed a close relationship with Moscow.

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Cold_War_(1953–62)

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk