A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Part of a series on |

| War |

|---|

|

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.[a]

Belligerents hold prisoners of war in custody for a range of legitimate and illegitimate reasons, such as isolating them from the enemy combatants still in the field (releasing and repatriating them in an orderly manner after hostilities), demonstrating military victory, using civilians to deter attacks on active military targets, punishing them, prosecuting them for war crimes, exploiting them for their labour, recruiting or even conscripting them as their own combatants, collecting military and political intelligence from them, or indoctrinating them in new political or religious beliefs.[1]

Under the 1949 Geneva Conventions, prisoners of war are automatically granted the enhanced status of protected persons, alongside certain civilians and enemy combatants who are hors de combat (i.e., out of the fight).[2]

Ancient times

For a large part of human history, prisoners of war would most often be either slaughtered or enslaved.[3] Early Roman gladiators could be prisoners of war, categorised according to their ethnic roots as Samnites, Thracians, and Gauls (Galli).[4] Homer's Iliad describes Trojan and Greek soldiers offering rewards of wealth to opposing forces who have defeated them on the battlefield in exchange for mercy, but their offers are not always accepted; see Lycaon for example.

Typically, victors made little distinction between enemy combatants and enemy civilians, although they were more likely to spare women and children. Sometimes the purpose of a battle, if not of a war, was to capture women, a practice known as raptio; the Rape of the Sabines involved, according to tradition, a large mass-abduction by the founders of Rome. Typically women had no rights, and were held legally as chattels.[citation needed][5][need quotation to verify]

In the fourth century AD, Bishop Acacius of Amida, touched by the plight of Persian prisoners captured in a recent war with the Greek Empire, who were held in his town under appalling conditions and destined for a life of slavery, took the initiative in ransoming them by selling his church's precious gold and silver vessels and letting them return to their country. For this he was eventually canonized.[6]

Middle Ages and Renaissance

According to legend, during Childeric's siege and blockade of Paris in 464 the nun Geneviève (later canonised as the city's patron saint) pleaded with the Frankish king for the welfare of prisoners of war and met with a favourable response. Later, Clovis I (r. 481–511) liberated captives after Genevieve urged him to do so.[7]

King Henry V's English army killed many French prisoners of war after the Battle of Agincourt in 1415.[8] This was done in retaliation for the French killing of the boys and other non-combatants handling the baggage and equipment of the army, and because the French were attacking again and Henry was afraid that they would break through and free the prisoners who would rejoin the fight against the English.

In the later Middle Ages a number of religious wars aimed to not only defeat but also to eliminate enemies. Authorities in Christian Europe often considered the extermination of heretics and heathens desirable. Examples of such wars include the 13th-century Albigensian Crusade in Languedoc and the Northern Crusades in the Baltic region.[9] When asked by a Crusader how to distinguish between the Catholics and Cathars following the projected capture (1209) of the city of Béziers, the papal legate Arnaud Amalric allegedly replied, "Kill them all, God will know His own".[b]

Likewise, the inhabitants of conquered cities were frequently massacred during Christians' Crusades against Muslims in the 11th and 12th centuries. Noblemen could hope to be ransomed; their families would have to send to their captors large sums of wealth commensurate with the social status of the captive.

Feudal Japan had no custom of ransoming prisoners of war, who could expect for the most part summary execution.[10]

In the 13th century the expanding Mongol Empire famously distinguished between cities or towns that surrendered (where the population was spared but required to support the conquering Mongol army) and those that resisted (in which case the city was ransacked and destroyed, and all the population killed). In Termez, on the Oxus: "all the people, both men and women, were driven out onto the plain, and divided in accordance with their usual custom, then they were all slain".[11]

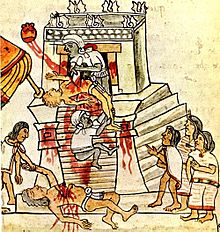

The Aztecs warred constantly with neighbouring tribes and groups, aiming to collect live prisoners for sacrifice.[12] For the re-consecration of Great Pyramid of Tenochtitlan in 1487, "between 10,000 and 80,400 persons" were sacrificed.[13][14]

During the early Muslim conquests of 622–750, Muslims routinely captured large numbers of prisoners. Aside from those who converted, most were ransomed or enslaved.[15][16] Christians captured during the Crusades were usually either killed or sold into slavery if they could not pay a ransom.[17] During his lifetime (c. 570 – 632), Muhammad made it the responsibility of the Islamic government to provide food and clothing, on a reasonable basis, to captives, regardless of their religion; however, if the prisoners were in the custody of a person, then the responsibility was on the individual.[18] On certain occasions where Muhammad felt the enemy had broken a treaty with the Muslims he endorsed the mass execution of male prisoners who participated in battles, as in the case of the Banu Qurayza in 627. The Muslims divided up the females and children of those executed as ghanima (spoils of war).[19]

Modern times

In Europe, the treatment of prisoners of war became increasingly centralized, in the time period between the 16th and late 18th century. Whereas prisoners of war had previously been regarded as the private property of the captor, captured enemy soldiers became increasingly regarded as the property of the state. The European states strove to exert increasing control over all stages of captivity, from the question of who would be attributed the status of prisoner of war to their eventual release. The act of surrender was regulated so that it, ideally, should be legitimized by officers, who negotiated the surrender of their whole unit.[20] Soldiers whose style of fighting did not conform to the battle line tactics of regular European armies, such as Cossacks and Croats, were often denied the status of prisoners of war.[21]

In line with this development the treatment of prisoners of war became increasingly regulated in international treaties, particularly in the form of the so-called cartel system, which regulated how the exchange of prisoners would be carried out between warring states.[22] Another such treaty was the 1648 Peace of Westphalia, which ended the Thirty Years' War. This treaty established the rule that prisoners of war should be released without ransom at the end of hostilities and that they should be allowed to return to their homelands.[23]

There also evolved the right of parole, French for "discourse", in which a captured officer surrendered his sword and gave his word as a gentleman in exchange for privileges. If he swore not to escape, he could gain better accommodations and the freedom of the prison. If he swore to cease hostilities against the nation who hold him captive, he could be repatriated or exchanged but could not serve against his former captors in a military capacity.

European settlers captured in North America

Early historical narratives of captured European settlers, including perspectives of literate women captured by the indigenous peoples of North America, exist in some number. The writings of Mary Rowlandson, captured in the chaotic fighting of King Philip's War, are an example. Such narratives enjoyed some popularity, spawning a genre of the captivity narrative, and had lasting influence on the body of early American literature, most notably through the legacy of James Fenimore Cooper's The Last of the Mohicans. Some Native Americans continued to capture Europeans and use them both as labourers and bargaining chips into the 19th century; see for example John R. Jewitt, a sailor who wrote a memoir about his years as a captive of the Nootka people on the Pacific Northwest coast from 1802 to 1805.

French Revolutionary wars and Napoleonic wars

The earliest known purpose-built prisoner-of-war camp was established at Norman Cross in Huntingdonshire, England in 1797 to house the increasing number of prisoners from the French Revolutionary Wars and the Napoleonic Wars.[24] The average prison population was about 5,500 men. The lowest number recorded was 3,300 in October 1804 and 6,272 on 10 April 1810 was the highest number of prisoners recorded in any official document. Norman Cross Prison was intended to be a model depot providing the most humane treatment of prisoners of war. The British government went to great lengths to provide food of a quality at least equal to that available to locals. The senior officer from each quadrangle was permitted to inspect the food as it was delivered to the prison to ensure it was of sufficient quality. Despite the generous supply and quality of food, some prisoners died of starvation after gambling away their rations. Most of the men held in the prison were low-ranking soldiers and sailors, including midshipmen and junior officers, with a small number of privateers. About 100 senior officers and some civilians "of good social standing", mainly passengers on captured ships and the wives of some officers, were given parole outside the prison, mainly in Peterborough although some further afield. They were afforded the courtesy of their rank within English society.

During the Battle of Leipzig both sides used the city's cemetery as a lazaret and prisoner camp for around 6,000 POWs who lived in the burial vaults and used the coffins for firewood. Food was scarce and prisoners resorted to eating horses, cats, dogs or even human flesh. The bad conditions inside the graveyard contributed to a city-wide epidemic after the battle.[25][26]

Prisoner exchanges

The extensive period of conflict during the American Revolutionary War and Napoleonic Wars (1793–1815), followed by the Anglo-American War of 1812, led to the emergence of a cartel system for the exchange of prisoners, even while the belligerents were at war. A cartel was usually arranged by the respective armed service for the exchange of like-ranked personnel. The aim was to achieve a reduction in the number of prisoners held, while at the same time alleviating shortages of skilled personnel in the home country.[citation needed]

American Civil War

At the start of the American Civil War a system of paroles operated. Captives agreed not to fight until they were officially exchanged. Meanwhile, they were held in camps run by their own army where they were paid but not allowed to perform any military duties.[27] The system of exchanges collapsed in 1863 when the Confederacy refused to exchange black prisoners. In the late summer of 1864, a year after the Dix–Hill Cartel was suspended, Confederate officials approached Union General Benjamin Butler, Union Commissioner of Exchange, about resuming the cartel and including the black prisoners. Butler contacted Grant for guidance on the issue, and Grant responded to Butler on 18 August 1864 with his now famous statement. He rejected the offer, stating in essence, that the Union could afford to leave their men in captivity, the Confederacy could not.[28] After that about 56,000 of the 409,000 POWs died in prisons during the American Civil War, accounting for nearly 10% of the conflict's fatalities.[29] Of the 45,000 Union prisoners of war confined in Camp Sumter, located near Andersonville, Georgia, 13,000 (28%) died.[30] At Camp Douglas in Chicago, Illinois, 10% of its Confederate prisoners died during one cold winter month; and Elmira Prison in New York state, with a death rate of 25% (2,963), nearly equalled that of Andersonville.[31]

Amelioration

During the 19th century, there were increased efforts to improve the treatment and processing of prisoners. As a result of these emerging conventions, a number of international conferences were held, starting with the Brussels Conference of 1874, with nations agreeing that it was necessary to prevent inhumane treatment of prisoners and the use of weapons causing unnecessary harm. Although no agreements were immediately ratified by the participating nations, work was continued that resulted in new conventions being adopted and becoming recognized as international law that specified that prisoners of war be treated humanely and diplomatically.

Hague and Geneva Conventions

Chapter II of the Annex to the 1907 Hague Convention IV – The Laws and Customs of War on Land covered the treatment of prisoners of war in detail. These provisions were further expanded in the 1929 Geneva Convention on the Prisoners of War and were largely revised in the Third Geneva Convention in 1949.

Article 4 of the Third Geneva Convention protects captured military personnel, some guerrilla fighters, and certain civilians. It applies from the moment a prisoner is captured until his or her release or repatriation. Under the 1949 Geneva Conventions, POWs acquires the status of protected persons, meaning it is a war crime by the detaining power to deprive the rights afforded to them by the Third Convention's provisions.[2] Article 17 of the Third Geneva Convention states that POWs can only be required to give their name, date of birth, rank and service number (if applicable).

The ICRC has a special role to play, with regards to international humanitarian law, in restoring and maintaining family contact in times of war, in particular concerning the right of prisoners of war and internees to send and receive letters and cards (Geneva Convention (GC) III, art. 71 and GC IV, art. 107).

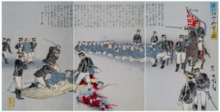

However, nations vary in their dedication to following these laws, and historically the treatment of POWs has varied greatly. During World War II, Imperial Japan and Nazi Germany (towards Soviet POWs and Western Allied commandos) were notorious for atrocities against prisoners of war. The German military used the Soviet Union's refusal to sign the Geneva Convention as a reason for not providing the necessities of life to Soviet POWs; and the Soviets also used Axis prisoners as forced labour. The Germans also routinely executed Allied commandos captured behind German lines per the Commando Order.

Qualifications

To be entitled to prisoner-of-war status, captured persons must be lawful combatants entitled to combatant's privilege—which gives them immunity from punishment for crimes constituting lawful acts of war such as killing enemy combatants. To qualify under the Third Geneva Convention, a combatant must be part of a chain of command, wear a "fixed distinctive marking, visible from a distance", bear arms openly, and have conducted military operations according to the laws and customs of war. (The Convention recognizes a few other groups as well, such as "nhabitants of a non-occupied territory, who on the approach of the enemy spontaneously take up arms to resist the invading forces, without having had time to form themselves into regular armed units".)

Thus, uniforms and badges are important in determining prisoner-of-war status under the Third Geneva Convention. Under Additional Protocol I, the requirement of a distinctive marking is no longer included. Francs-tireurs, militias, insurgents, terrorists, saboteurs, mercenaries, and spies generally do not qualify because they do not fulfill the criteria of Additional Protocol I. Therefore, they fall under the category of unlawful combatants, or more properly they are not combatants. Captured soldiers who do not get prisoner of war status are still protected like civilians under the Fourth Geneva Convention.

The criteria are applied primarily to international armed conflicts. The application of prisoner of war status in non-international armed conflicts like civil wars is guided by Additional Protocol II, but insurgents are often treated as traitors, terrorists or criminals by government forces and are sometimes executed on spot or tortured. However, in the American Civil War, both sides treated captured troops as POWs presumably out of reciprocity, although the Union regarded Confederate personnel as separatist rebels. However, guerrillas and other irregular combatants generally cannot expect to receive benefits from both civilian and military status simultaneously.

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Prisoner_of_warText je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk