A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Danish | |

|---|---|

| dansk | |

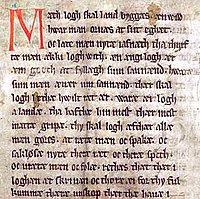

The first page of the Jutlandic Law originally from 1241 in Codex Holmiensis, copied in 1350. The first sentence is: "Mæth logh skal land byggas" Modern orthography: "Med lov skal land bygges" English translation: "With law shall a country be built" | |

| Pronunciation | [ˈtænˀsk][1] |

| Native to | |

| Region | Denmark, Schleswig-Holstein (Germany); Additionally in the Faroe Islands and Greenland |

| Ethnicity | |

Native speakers | 6.0 million (2019)[2] |

Early forms | |

| Dialects | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Regulated by | Dansk Sprognævn (Danish Language Council) |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | da |

| ISO 639-2 | dan |

| ISO 639-3 | Either:dan – Insular Danishjut – Jutlandic |

| Glottolog | dani1285 Danishjuti1236 Jutish |

| Linguasphere | 5 2-AAA-bf & -ca to -cj |

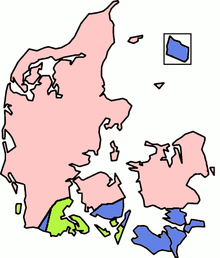

Dark Blue: Spoken by a majority

Light Blue: Spoken by a minority | |

Danish (/ˈdeɪnɪʃ/ ⓘ, DAY-nish; endonym: dansk pronounced [ˈtænˀsk] ⓘ, dansk sprog [ˈtænˀsk ˈspʁɔwˀ])[1] is a North Germanic language from the Indo-European language family spoken by about six million people, principally in and around Denmark. Communities of Danish speakers are also found in Greenland,[5] the Faroe Islands, and the northern German region of Southern Schleswig, where it has minority language status.[6][7] Minor Danish-speaking communities are also found in Norway, Sweden, the United States, Canada, Brazil, and Argentina.[8]

Along with the other North Germanic languages, Danish is a descendant of Old Norse, the common language of the Germanic peoples who lived in Scandinavia during the Viking Era. Danish, together with Swedish, derives from the East Norse dialect group, while the Middle Norwegian language (before the influence of Danish) and Norwegian Bokmål are classified as West Norse along with Faroese and Icelandic. A more recent classification based on mutual intelligibility separates modern spoken Danish, Norwegian, and Swedish as "mainland (or continental) Scandinavian", while Icelandic and Faroese are classified as "insular Scandinavian". Although the written languages are compatible, spoken Danish is distinctly different from Norwegian and Swedish and thus the degree of mutual intelligibility with either is variable between regions and speakers.

Until the 16th century, Danish was a continuum of dialects spoken from Southern Jutland and Schleswig to Scania with no standard variety or spelling conventions. With the Protestant Reformation and the introduction of the printing press, a standard language was developed which was based on the educated dialect of Copenhagen and Malmö.[9] It spread through use in the education system and administration, though German and Latin continued to be the most important written languages well into the 17th century. Following the loss of territory to Germany and Sweden, a nationalist movement adopted the language as a token of Danish identity, and the language experienced a strong surge in use and popularity, with major works of literature produced in the 18th and 19th centuries. Today, traditional Danish dialects have all but disappeared, though regional variants of the standard language exist. The main differences in language are between generations, with youth language being particularly innovative.

Danish has a very large vowel inventory consisting of 27 phonemically distinctive vowels,[10] and its prosody is characterized by the distinctive phenomenon stød, a kind of laryngeal phonation type. Due to the many pronunciation differences that set Danish apart from its neighboring languages, particularly the vowels, difficult prosody and "weakly" pronounced consonants, it is sometimes considered to be a "difficult language to learn, acquire and understand",[11][12] and some evidence shows that children are slower to acquire the phonological distinctions of Danish compared to other languages.[13] The grammar is moderately inflective with strong (irregular) and weak (regular) conjugations and inflections. Nouns, adjectives, and demonstrative pronouns distinguish common and neutral gender. Like English, Danish only has remnants of a former case system, particularly in the pronouns. Unlike English, it has lost all person marking on verbs. Its word order is V2, with the finite verb always occupying the second slot in the sentence.

Classification

Danish is a Germanic language of the North Germanic branch. Other names for this group are the Nordic[14] or Scandinavian languages. Along with Swedish, Danish descends from the Eastern dialects of the Old Norse language; Danish and Swedish are also classified as East Scandinavian or East Nordic languages.[15][16]

Scandinavian languages are often considered a dialect continuum, where no sharp dividing lines are seen between the different vernacular languages.[15]

Like Norwegian and Swedish, Danish was significantly influenced by Low German in the Middle Ages, and has been influenced by English since the turn of the 20th century.[15]

Danish itself can be divided into three main dialect areas: Jutlandic (West Danish), Insular Danish (including the standard variety), and East Danish (including Bornholmian and Scanian). Under the view that Scandinavian is a dialect continuum, East Danish can be considered intermediary between Danish and Swedish, while Scanian can be considered a Swedified East Danish dialect, and Bornholmian is its closest relative.[15]

Vocabulary

Approximately 2,000 uncompounded Danish words are derived from Old Norse and ultimately from Proto Indo-European. Of these 2,000, 1,200 are nouns, 500 are verbs and 180 are adjectives.[17] Danish has also absorbed many loanwords, most of which were borrowed from Low German of the Late Middle Ages. Out of the 500 most frequently used Danish words, 100 are loans from Middle Low German; this is because Low German was the second official language of Denmark–Norway.[18] In the 17th and 18th centuries, standard German and French superseded Low German influence, and in the 20th century, English became the main supplier of loanwords, especially after World War II. Although many old Nordic words remain, some were replaced with borrowed synonyms, for example æde (to eat) was mostly supplanted by the Low German spise. As well as loanwords, new words can be freely formed by compounding existing words. In standard texts of contemporary Danish, Middle Low German loans account for about 16–17% of the vocabulary, Graeco-Latin loans 4–8%, French 2–4% and English about 1%.[18]

Danish and English are both Germanic languages. Danish is a North Germanic language descended from Old Norse, and English is a West Germanic language descended from Old English. Old Norse exerted a strong influence on Old English in the early medieval period.

The shared Germanic heritage of Danish and English is demonstrated with many common words that are very similar in the two languages. For example, when written, commonly used Danish verbs, nouns, and prepositions such as have, over, under, for, give, flag, salt, and arm are easily recognizable to English speakers.[19] Similarly, some other words are almost identical to their Scots equivalents, e.g., kirke (Scots kirk, i.e., 'church') or barn (Scots bairn, i.e. 'child'). In addition, the word by, meaning "village" or "town", occurs in many English place-names, such as Whitby and Selby, as remnants of the Viking occupation. During the latter period, English adopted "are", the third person plural form of the verb "to be", as well as the personal pronouns "they", "them" and "their" from contemporary Old Norse.

Mutual intelligibility

Danish is largely mutually intelligible with Norwegian and Swedish. A proficient speaker of any of the three languages can often understand the others fairly well, though studies have shown that the mutual intelligibility is asymmetric: Norwegian speakers generally understand both Danish and Swedish far better than Swedes or Danes understand each other. Concomitantly, Swedes and Danes understand Norwegian better than they understand each other's languages.[20]

Norwegian occupies the middle position in terms of intelligibility because of its shared border with Sweden, resulting in a similarity in pronunciation, combined with the long tradition of having Danish as a written language, which has led to similarities in vocabulary.[21] Among younger Danes, Copenhageners are worse at understanding Swedish than Danes from the provinces. In general, younger Danes are not as good at understanding the neighboring languages as the young in Norway and Sweden.[20]

History

The Danish philologist Johannes Brøndum-Nielsen divided the history of Danish into a period from 800 AD to 1525 to be "Old Danish", which he subdivided into "Runic Danish" (800–1100), Early Middle Danish (1100–1350) and Late Middle Danish (1350–1525).[22]

Runic Danish

Móðir Dyggva var Drótt, dóttir Danps konungs, sonar Rígs er fyrstr var konungr kallaðr á danska tungu.

"Dyggvi's mother was Drott, the daughter of king Danp, Ríg's son, who was the first to be called king in the Danish tongue."

By the eighth century, the common Germanic language of Scandinavia, Proto-Norse, had undergone some changes and evolved into Old Norse. This language was generally called the "Danish tongue" (Dǫnsk tunga), or "Norse language" (Norrœnt mál). Norse was written in the runic alphabet, first with the elder futhark and from the 9th century with the younger futhark.[24]

From the seventh century, the common Norse language began to undergo changes that did not spread to all of Scandinavia, resulting in the appearance of two dialect areas, Old West Norse (Norway and Iceland) and Old East Norse (Denmark and Sweden). Most of the changes separating East Norse from West Norse started as innovations in Denmark, that spread through Scania into Sweden and by maritime contact to southern Norway.[25] A change that separated Old East Norse (Runic Swedish/Danish) from Old West Norse was the change of the diphthong æi (Old West Norse ei) to the monophthong e, as in stæin to sten. This is reflected in runic inscriptions where the older read stain and the later stin. Also, a change of au as in dauðr into ø as in døðr occurred. This change is shown in runic inscriptions as a change from tauþr into tuþr. Moreover, the øy (Old West Norse ey) diphthong changed into ø, as well, as in the Old Norse word for "island". This monophthongization started in Jutland and spread eastward, having spread throughout Denmark and most of Sweden by 1100.[26]

Through Danish conquest, Old East Norse was once widely spoken in the northeast counties of England. Many words derived from Norse, such as "gate" (gade) for street, still survive in Yorkshire, the East Midlands and East Anglia, and parts of eastern England colonized by Danish Vikings. The city of York was once the Viking settlement of Jorvik. Several other English words derive from Old East Norse, for example "knife" (kniv), "husband" (husbond), and "egg" (æg). The suffix "-by" for 'town' is common in place names in Yorkshire and the east Midlands, for example Selby, Whitby, Derby, and Grimsby. The word "dale" meaning valley is common in Yorkshire and Derbyshire placenames.[27]

Old and Middle dialects

Fangær man saar i hor seng mæth annæns mansz kunæ. oc kumær han burt liuænd....

"If one catches someone in the whore-bed with another man's wife and he comes away alive..."

Jutlandic Law, 1241[28]

In the medieval period, Danish emerged as a separate language from Swedish. The main written language was Latin, and the few Danish-language texts preserved from this period are written in the Latin alphabet, although the runic alphabet seems to have lingered in popular usage in some areas. The main text types written in this period are laws, which were formulated in the vernacular language to be accessible also to those who were not Latinate. The Jutlandic Law and Scanian Law were written in vernacular Danish in the early 13th century. Beginning in 1350, Danish began to be used as a language of administration, and new types of literature began to be written in the language, such as royal letters and testaments. The orthography in this period was not standardized nor was the spoken language, and the regional laws demonstrate the dialectal differences between the regions in which they were written.[29]

Throughout this period, Danish was in contact with Low German, and many Low German loan words were introduced in this period.[30] With the Protestant Reformation in 1536, Danish also became the language of religion, which sparked a new interest in using Danish as a literary language. Also in this period, Danish began to take on the linguistic traits that differentiate it from Swedish and Norwegian, such as the stød, the voicing of many stop consonants, and the weakening of many final vowels to /e/.[31]

The first printed book in Danish dates from 1495, the Rimkrøniken (Rhyming Chronicle), a history book told in rhymed verses.[32] The first complete translation of the Bible in Danish, the Bible of Christian II translated by Christiern Pedersen, was published in 1550. Pedersen's orthographic choices set the de facto standard for subsequent writing in Danish.[33] From around 1500, several printing presses were in operation in Denmark publishing in Danish and other languages. In the period after 1550, presses in Copenhagen dominated the publication of material in the Danish language.[9]

Early Modern

Herrer og Narre have frit Sprog.

"Lords and jesters have free speech."

Peder Syv, proverbs

Following the first Bible translation, the development of Danish as a written language, as a language of religion, administration, and public discourse accelerated. In the second half of the 17th century, grammarians elaborated grammars of Danish, first among them Rasmus Bartholin's 1657 Latin grammar De studio lingvæ danicæ; then Laurids Olufsen Kock's 1660 grammar of the Zealand dialect Introductio ad lingvam Danicam puta selandicam; and in 1685 the first Danish grammar written in Danish, Den Danske Sprog-Kunst ("The Art of the Danish Language") by Peder Syv. Major authors from this period are Thomas Kingo, poet and psalmist, and Leonora Christina Ulfeldt, whose novel Jammersminde (Remembered Woes) is considered a literary masterpiece by scholars. Orthography was still not standardized and the principles for doing so were vigorously discussed among Danish philologists. The grammar of Jens Pedersen Høysgaard was the first to give a detailed analysis of Danish phonology and prosody, including a description of the stød. In this period, scholars were also discussing whether it was best to "write as one speaks" or to "speak as one writes", including whether archaic grammatical forms that had fallen out of use in the vernacular, such as the plural form of verbs, should be conserved in writing (i.e. han er "he is" vs. de ere "they are").[34]

The East Danish provinces were lost to Sweden after the Second Treaty of Brömsebro (1645) after which they were gradually Swedified; just as Norway was politically severed from Denmark, beginning also a gradual end of Danish influence on Norwegian (influence through the shared written standard language remained). With the introduction of absolutism in 1660, the Danish state was further integrated, and the language of the Danish chancellery, a Zealandic variety with German and French influence, became the de facto official standard language, especially in writing—this was the original so-called rigsdansk ("Danish of the Realm"). Also, beginning in the mid-18th century, the skarre-R, the uvular R sound (), began spreading through Denmark, likely through influence from Parisian French and German. It affected all of the areas where Danish had been influential, including all of Denmark, Southern Sweden, and coastal southern Norway.[35]

In the 18th century, Danish philology was advanced by Rasmus Rask, who pioneered the disciplines of comparative and historical linguistics, and wrote the first English-language grammar of Danish. Literary Danish continued to develop with the works of Ludvig Holberg, whose plays and historical and scientific works laid the foundation for the Danish literary canon. With the Danish colonization of Greenland by Hans Egede, Danish became the administrative and religious language there, while Iceland and the Faroe Islands had the status of Danish colonies with Danish as an official language until the mid-20th century.[34]

Standardized national language

Moders navn er vort Hjertesprog,

kun løs er al fremmed Tale.

Det alene i mund og bog,

kan vække et folk af dvale.

"Mother's name is our hearts' tongue,

only idle is all foreign speech

It alone, in mouth or in book,

can rouse a people from sleep."

N.F.S. Grundtvig, "Modersmaalet"

Following the loss of Schleswig to Germany, a sharp influx of German speakers moved into the area, eventually outnumbering the Danish speakers. The political loss of territory sparked a period of intense nationalism in Denmark, coinciding with the so-called "Golden Age" of Danish culture. Authors such as N.F.S. Grundtvig emphasized the role of language in creating national belonging. Some of the most cherished Danish-language authors of this period are existential philosopher Søren Kierkegaard and prolific fairy tale author Hans Christian Andersen.[36] The influence of popular literary role models, together with increased requirements of education did much to strengthen the Danish language, and also started a period of homogenization, whereby the Copenhagen standard language gradually displaced the regional vernacular languages. Throughout the 19th century, Danes emigrated, establishing small expatriate communities in the Americas, particularly in the United States, Canada, and Argentina, where memory and some use of Danish remains today.

After the Schleswig referendum in 1920, a number of Danes remained as a minority within German territories.[37] After the occupation of Denmark by Germany in World War II, the 1948 orthography reform dropped the German-influenced rule of capitalizing nouns, and introduced the letter ⟨å⟩. Three 20th-century Danish authors have become Nobel Prize laureates in Literature: Karl Gjellerup and Henrik Pontoppidan (joint recipients in 1917) and Johannes V. Jensen (awarded 1944).

With the exclusive use of rigsdansk, the High Copenhagen Standard, in national broadcasting, the traditional dialects came under increased pressure. In the 20th century, they have all but disappeared, and the standard language has extended throughout the country.[38] Minor regional pronunciation variation of the standard language, sometimes called regionssprog ("regional languages") remain, and are in some cases vital. Today, the major varieties of Standard Danish are High Copenhagen Standard, associated with elderly, well to-do, and well educated people of the capital, and low Copenhagen speech traditionally associated with the working class, but today adopted as the prestige variety of the younger generations.[39][40] Also, in the 21st century, the influence of immigration has had linguistic consequences, such as the emergence of a so-called multiethnolect in the urban areas, an immigrant Danish variety (also known as Perkerdansk), combining elements of different immigrant languages such as Arabic, Turkish, and Kurdish, as well as English and Danish.[39]

Geographic distribution and status

Danish Realm

Within the Danish Realm, Danish is the national language of Denmark and one of two official languages of the Faroe Islands (alongside Faroese). There is a Faroese variant of Danish known as Gøtudanskt. Until 2009, Danish was also one of two official languages of Greenland (alongside Greenlandic). Danish now acts as a lingua franca in Greenland, with a large percentage of native Greenlanders able to speak Danish as a second language (it was introduced into the education system as a compulsory language in 1928). About 10% of the population speaks Danish as their first language, due to immigration.[5]

Iceland was a territory ruled by Denmark–Norway, one of whose official languages was Danish.[41] Though Danish ceased to be an official language in Iceland in 1944, it is still widely used and is a mandatory subject in school, taught as a second foreign language after English.

No law stipulates an official language for Denmark, making Danish the de facto official language only. The Code of Civil Procedure does, however, lay down Danish as the language of the courts.[42] Since 1997, public authorities have been obliged to follow the official spelling system laid out in the Orthography Law. In the 21st century, discussions have been held with a view to create a law that would make Danish the official language of Denmark.[43]

Surrounding countries

In addition, a noticeable community of Danish speakers is in Southern Schleswig, the portion of Germany bordering Denmark, and a variant of Standard Danish, Southern Schleswig Danish, is spoken in the area. Since 2015, Schleswig-Holstein has officially recognized Danish as a regional language,[6][7] just as German is north of the border. Furthermore, Danish is one of the official languages of the European Union and one of the working languages of the Nordic Council.[44] Under the Nordic Language Convention, Danish-speaking citizens of the Nordic countries have the opportunity to use their native language when interacting with official bodies in other Nordic countries without being liable for any interpretation or translation costs.[44]

The more widespread of the two varieties of written Norwegian, Bokmål, is very close to Danish, because standard Danish was used as the de facto administrative language until 1814 and one of the official languages of Denmark–Norway. Bokmål is based on Danish, unlike the other variety of Norwegian, Nynorsk, which is based on the Norwegian dialects, with Old Norwegian as an important reference point.[15] Also North Frisian[45] and Gutnish (Gutamål) were influenced by Danish.[46]

Other locations

There are also Danish emigrant communities in other places of the world who still use the language in some form. In the Americas, Danish-speaking communities can be found in the US, Canada, Argentina and Brazil.[8]

Dialects

Standard Danish (rigsdansk) is the language based on dialects spoken in and around the capital, Copenhagen. Unlike Swedish and Norwegian, Danish does not have more than one regional speech norm. More than 25% of all Danish speakers live in the metropolitan area of the capital, and most government agencies, institutions, and major businesses keep their main offices in Copenhagen, which has resulted in a very homogeneous national speech norm.[38][15]

Danish dialects can be divided into the traditional dialects, which differ from modern Standard Danish in both phonology and grammar, and the Danish accents or regional languages, which are local varieties of the Standard language distinguished mostly by pronunciation and local vocabulary colored by traditional dialects. Traditional dialects are now mostly extinct in Denmark, with only the oldest generations still speaking them.[47][38]

Danish traditional dialects are divided into three main dialect areas:

- Insular Danish (ømål), including dialects of the Danish islands of Zealand, Funen, Lolland, Falster, and Møn[48]

- Jutlandic (jysk), further divided in North, East, West, and South Jutlandic[49]

- East Danish (østdansk), including dialects of Bornholm (bornholmsk), Scania, Halland and Blekinge [50]

Jutlandic is further divided into Southern Jutlandic and Northern Jutlandic, with Northern Jutlandic subdivided into North Jutlandic and West Jutlandic. Insular Danish is divided into Zealand, Funen, Møn, and Lolland-Falster dialect areas―each with addition internal variation. Bornholmian is the only Eastern Danish dialect spoken in Denmark. Since the Swedish conquest of the Eastern Danish provinces Skåne, Halland and Blekinge in 1645/1658, the Eastern Danish dialects there have come under heavy Swedish influence. Many residents now speak regional variants of Standard Swedish. However, many researchers still consider the dialects in Scania, Halland (hallandsk) and Blekinge (blekingsk) as part of the East Danish dialect group.[51][52][53] The Swedish National Encyclopedia from 1995 classifies Scanian as an Eastern Danish dialect with South Swedish elements.[54]

Traditional dialects differ in phonology, grammar, and vocabulary from standard Danish. Phonologically, one of the most diagnostic differences is the presence or absence of stød.[55] Four main regional variants for the realization of stød are known: In Southeastern Jutlandic, Southernmost Funen, Southern Langeland, and Ærø, no stød is used, but instead a pitch accent (like in Norwegian, Swedish and Gutnish). South of a line (stødgrænsen, 'the stød border') going through central South Jutland, crossing Southern Funen and central Langeland and north of Lolland-Falster, Møn, Southern Zealand and Bornholm neither stød nor pitch accent exists.[56] Most of Jutland and on Zealand use stød, and in Zealandic traditional dialects and regional language, stød occurs more often than in the standard language. In Zealand, the stød line divides Southern Zealand (without stød), an area which used to be directly under the Crown, from the rest of the Island that used to be the property of various noble estates.[57][58]

Grammatically, a dialectally significant feature is the number of grammatical genders. Standard Danish has two genders and the definite form of nouns is formed by the use of suffixes, while Western Jutlandic has only one gender and the definite form of nouns uses an article before the noun itself, in the same fashion as West Germanic languages. The Bornholmian dialect has maintained to this day many archaic features, such as a distinction between three grammatical genders.[50] Insular Danish traditional dialects also conserved three grammatical genders. By 1900, Zealand insular dialects had been reduced to two genders under influence from the standard language, but other Insular varieties, such as Funen dialect had not.[59] Besides using three genders, the old Insular or Funen dialect, could also use personal pronouns (like he and she) in certain cases, particularly referring to animals. A classic example in traditional Funen dialect is the sentence: "Katti, han får unger", literally The cat, he is having kittens, because cat is a masculine noun, thus is referred to as han (he), even if it is a female cat.[60]

Phonology

The sound system of Danish is unusual, particularly in its large vowel inventory and in the unusual prosody. In informal or rapid speech, the language is prone to considerable reduction of unstressed syllables, creating many vowel-less syllables with syllabic consonants, as well as reduction of final consonants. Furthermore, the language's prosody does not include many clues about the sentence structure, unlike many other languages, making it relatively more difficult to perceive the different sounds of the speech flow.[11][12] These factors taken together make Danish pronunciation difficult to master for learners, and Danish children are indicated to take slightly longer in learning to segment speech in early childhood.[13]

Vowels

Although somewhat depending on analysis, most modern variants of Danish distinguish 12 long vowels, 13 short vowels, and two central vowels, /ə/ and /ɐ/, which only occur in unstressed syllables. This gives a total of 27 different vowel phonemes – a very large number among the world's languages.[61] At least 19 different diphthongs also occur, all with a short first vowel and the second segment being either , , or .[62] The table below shows the approximate distribution of the vowels as given by Grønnum (1998a) in Modern Standard Danish, with the symbols used in IPA/Danish. Questions of analysis may give a slightly different inventory, for example based on whether r-colored vowels are considered distinct phonemes. Basbøll (2005:50) gives 25 "full vowels", not counting the two unstressed "schwa" vowels.

| Front | Central | Back | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| unrounded | rounded | |||||||

| short | long | short | long | short | long | short | long | |

| Close | i | iː | y | yː | u | uː | ||

| Close-mid | e | eː | ø | øː | ə | o | oː | |

| Open-mid | ɛ | ɛː | œ | œː | ɐ | ɔ | ɔː | |

| Open | a | aː | ɑ | ɑː | ɒ | ɒː | ||

Consonants

The consonant inventory is comparatively simple. Basbøll (2005:73) distinguishes 17 non-syllabic consonant phonemes in Danish.

| Labial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Uvular/ Pharyngeal[63] |

Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ŋ | |||

| Stop | p b | t d | k ɡ | |||

| Fricative | f | s | h | |||

| Approximant | ʋ | l ð | j | ʁ |

Many of these phonemes have quite different allophones in onset and coda where intervocalic consonants followed by a full vowel are treated as in onset, otherwise as in coda.[64] Phonetically there is no voicing distinction among the stops, rather the distinction is one of aspiration.[62] /p t k/ are aspirated in onset realized as pʰ, tsʰ, kʰ, but not in coda. The pronunciation of t, tsʰ, is in between a simple aspirated tʰ and a fully affricated tsʰ (as has happened in German with the second High German consonant shift from t to z). There is dialectal variation, and some Jutlandic dialects may be less affricated than other varieties, with Northern and Western Jutlandic traditional dialects having an almost unaspirated dry t.[65]

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Danish_language

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk