A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Part of a series on |

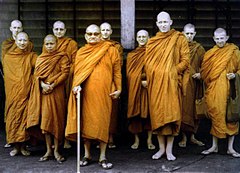

| Theravāda Buddhism |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Buddhism |

|---|

|

Theravāda (/ˌtɛrəˈvɑːdə/,[a] lit. 'School of the Elders'[1][2]) is the most commonly accepted name of Buddhism's oldest existing school.[1][2] The school's adherents, termed Theravādins, have preserved their version of Gautama Buddha's teaching or Buddha Dhamma in the Pāli Canon for over two millennia.[1][2][web 1]

The Pāli Canon is the most complete Buddhist canon surviving in a classical Indian language, Pāli, which serves as the school's sacred language[2] and lingua franca.[3] In contrast to Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna, Theravāda tends to be conservative in matters of doctrine (pariyatti) and monastic discipline (vinaya).[4] One element of this conservatism is the fact that Theravāda rejects the authenticity of the Mahayana sutras (which appeared c. 1st century BCE onwards).[5][6]

Modern Theravāda derives from the Mahāvihāra order, a Sri Lankan branch of the Vibhajjavāda tradition, which is, in turn, a sect of the Indian Sthavira Nikaya. This tradition began to establish itself in Sri Lanka from the 3rd century BCE onwards. It was in Sri Lanka that the Pāli Canon was written down and the school's commentary literature developed. From Sri Lanka, the Theravāda Mahāvihāra tradition subsequently spread to Southeast Asia.[7] Theravāda is the official religion of Sri Lanka, Myanmar and Cambodia, and the main dominant Buddhist variant found in Laos and Thailand and is practiced by minorities in India, Bangladesh, China, Nepal, North Korea, Vietnam, the Philippines and Taiwan. The diaspora of all of these groups, as well as converts around the world, also embrace and practice Theravāda Buddhism.

During the modern era, new developments have included Buddhist modernism, the Vipassana movement which reinvigorated Theravāda meditation practice,[web 1] the growth of the Thai Forest Tradition which reemphasized forest monasticism and the spread of Theravāda westward to places such as India and Nepal, along with Buddhist immigrants and converts in the European Union and the United States.

History

Pre-Modern

The Theravāda school descends from the Vibhajjavāda, a division within the Sthāvira nikāya, one of the two major orders that arose after the first schism in the Indian Buddhist community.[8][9] Theravāda sources trace their tradition to the Third Buddhist council when elder Moggaliputta-Tissa is said to have compiled the Kathavatthu, an important work which lays out the Vibhajjavāda doctrinal position.[10]

Aided by the patronage of Mauryan kings like Ashoka, this school spread throughout India and reached Sri Lanka through the efforts of missionary monks like Mahinda. In Sri Lanka, it became known as the Tambapaṇṇiya (and later as Mahāvihāravāsins) which was based at the Great Vihara (Mahavihara) in Anuradhapura (the ancient Sri Lankan capital).[11] According to Theravāda sources, another one of the Ashokan missions was also sent to Suvaṇṇabhūmi ("The Golden Land"), which may refer to Southeast Asia.[12]

By the first century BCE, Theravāda Buddhism was well established in the main settlements of the Kingdom of Anuradhapura.[13] The Pali Canon, which contains the main scriptures of the Theravāda, was committed to writing in the first century BCE.[14] Throughout the history of ancient and medieval Sri Lanka, Theravāda was the main religion of the Sinhalese people and its temples and monasteries were patronized by the Sri Lankan kings, who saw themselves as the protectors of the religion.[15]

Over time, two other sects split off from the Mahāvihāra tradition, the Abhayagiri and Jetavana.[17] While the Abhayagiri sect became known for the syncretic study of Mahayana and Vajrayana texts, as well as the Theravāda canon, the Mahāvihāra tradition did not accept these new scriptures.[18] Instead, Mahāvihāra scholars like Buddhaghosa focused on the exegesis of the Pali scriptures and on the Abhidhamma. These Theravāda sub-sects often came into conflict with each other over royal patronage.[19] The reign of Parākramabāhu I (1153–1186) saw an extensive reform of the Sri Lankan sangha after years of warfare on the island. Parākramabāhu created a single unified sangha which came to be dominated by the Mahāvihāra sect.[20][21]

Epigraphical evidence has established that Theravāda Buddhism became a dominant religion in the Southeast Asian kingdoms of Sri Ksetra and Dvaravati from about the 5th century CE onwards.[22] The oldest surviving Buddhist texts in the Pāli language are gold plates found at Sri Ksetra dated circa the 5th to 6th century.[23] Before the Theravāda tradition became the dominant religion in Southeast Asia, Mahāyāna, Vajrayana and Hinduism were also prominent.[24][25]

Starting at around the 11th century, Sinhalese Theravāda monks and Southeast Asian elites led a widespread conversion of most of mainland Southeast Asia to the Theravādin Mahavihara school.[26] The patronage of monarchs such as the Burmese king Anawrahta (Pali: Aniruddha, 1044–1077) and the Thai king Ram Khamhaeng (floruit. late 13th century) was instrumental in the rise of Theravāda Buddhism as the predominant religion of Burma and Thailand.[27][28][29]

Burmese and Thai kings saw themselves as Dhamma Kings and as protectors of the Theravāda faith. They promoted the building of new temples, patronized scholarship, monastic ordinations and missionary works as well as attempted to eliminate certain non-Buddhist practices like animal sacrifices.[30][31][32] During the 15th and 16th centuries, Theravāda also became established as the state religion in Cambodia and Laos. In Cambodia, numerous Hindu and Mahayana temples, most famously Angkor Wat and Angkor Thom, were transformed into Theravādin monasteries.[33][34]

Modern history

In the 19th and 20th centuries, Theravāda Buddhists came into direct contact with western ideologies, religions and modern science. The various responses to this encounter have been called "Buddhist modernism".[35] In the British colonies of Ceylon (modern Sri Lanka) and Burma (Myanmar), Buddhist institutions lost their traditional role as the prime providers of education (a role that was often filled by Christian schools).[36] In response to this, Buddhist organizations were founded which sought to preserve Buddhist scholarship and provide a Buddhist education.[37] Anagarika Dhammapala, Migettuwatte Gunananda Thera, Hikkaduwe Sri Sumangala Thera and Henry Steel Olcott (one of the first American western converts to Buddhism) were some of the main figures of the Sri Lankan Buddhist revival.[38] Two new monastic orders were formed in the 19th century, the Amarapura Nikāya and the Rāmañña Nikāya.[39]

In Burma, an influential modernist figure was king Mindon Min (1808–1878), known for his patronage of the Fifth Buddhist council (1871) and the Tripiṭaka tablets at Kuthodaw Pagoda (still the world's largest book) with the intention of preserving the Buddha Dhamma. Burma also saw the growth of the "Vipassana movement", which focused on reviving Buddhist meditation and doctrinal learning. Ledi Sayadaw (1846–1923) was one of the key figures in this movement.[40] After independence, Myanmar held the Sixth Buddhist council (Vesak 1954 to Vesak 1956) to create a new redaction of the Pāli Canon, which was then published by the government in 40 volumes. The Vipassana movement continued to grow after independence, becoming an international movement with centers around the world. Influential meditation teachers of the post-independence era include U Narada, Mahasi Sayadaw, Sayadaw U Pandita, Nyanaponika Thera, Webu Sayadaw, U Ba Khin and his student S.N. Goenka.

Meanwhile, in Thailand (the only Theravāda nation to retain its independence throughout the colonial era), the religion became much more centralized, bureaucratized and controlled by the state after a series of reforms promoted by Thai kings of the Chakri dynasty. King Mongkut (r. 1851–1868) and his successor Chulalongkorn (1868–1910) were especially involved in centralizing sangha reforms. Under these kings, the sangha was organized into a hierarchical bureaucracy led by the Sangha Council of Elders (Pali: Mahāthera Samāgama), the highest body of the Thai sangha.[41] Mongkut also led the creation of a new monastic order, the Dhammayuttika Nikaya, which kept a stricter monastic discipline than the rest of the Thai sangha (this included not using money, not storing up food and not taking milk in the evening).[42][43] The Dhammayuttika movement was characterized by an emphasis on the original Pali Canon and a rejection of Thai folk beliefs which were seen as irrational.[44] Under the leadership of Prince Wachirayan Warorot, a new education and examination system was introduced for Thai monks.[45]

The 20th century also saw the growth of "forest traditions" which focused on forest living and strict monastic discipline. The main forest movements of this era are the Sri Lankan Forest Tradition and the Thai Forest Tradition, founded by Ajahn Mun (1870–1949) and his students.[46]

Theravāda Buddhism in Cambodia and Laos went through similar experiences in the modern era. Both had to endure French colonialism, destructive civil wars and oppressive communist governments. Under French Rule, French indologists of the École française d'Extrême-Orient became involved in the reform of Buddhism, setting up institutions for the training of Cambodian and Lao monks, such as the Ecole de Pali which was founded in Phnom Penh in 1914.[47] While the Khmer Rouge effectively destroyed Cambodia's Buddhist institutions, after the end of the communist regime the Cambodian Sangha was re-established by monks who had returned from exile.[48] In contrast, communist rule in Laos was less destructive since the Pathet Lao sought to make use of the sangha for political ends by imposing direct state control.[49] During the late 1980s and 1990s, the official attitudes toward Buddhism began to liberalise in Laos and there was a resurgence of traditional Buddhist activities such as merit-making and doctrinal study.

The modern era also saw the spread of Theravāda Buddhism around the world and the revival of the religion in places where it remains a minority faith. Some of the major events of the spread of modern Theravāda include:

- The 20th-century Nepalese Theravāda movement which introduced Theravāda Buddhism to Nepal and was led by prominent figures such as Dharmaditya Dharmacharya, Mahapragya, Pragyananda and Dhammalok Mahasthavir.[50]

- The establishment of some of the first Theravāda Viharas in the Western world, such as the London Buddhist Vihara (1926), Das Buddhistische Haus in Berlin (1957) and the Washington Buddhist Vihara in Washington, DC (1965).

- The founding of the Bengal Buddhist Association (1892) and the Dharmankur Vihar (1900) in Calcutta by the Bengali monk Kripasaran Mahasthavir, which were key events in the Bengali Theravāda revival.[51]

- The founding of the Maha Bodhi Society in 1891 by Anagarika Dharmapala which focused on the conservation and restoration of important Indian Buddhist sites, such as Bodh Gaya and Sarnath.[52][53]

- The introduction of Theravāda to other Southeast Asian nations like Singapore, Indonesia and Malaysia. Especially with Ven. K. Sri Dhammananda missionary efforts among English-speaking Chinese communities.

- The return of Western Theravādin monks trained in the Thai Forest Tradition to western countries and the subsequent founding of monasteries led by western monastics, such as Abhayagiri Buddhist Monastery, Chithurst Buddhist Monastery, Metta Forest Monastery, Amaravati Buddhist Monastery, Birken Forest Buddhist Monastery, Bodhinyana Monastery and Santacittarama.

- The spread of the Vipassana movement around the world by the efforts of people like S.N. Goenka, Anagarika Munindra, Joseph Goldstein, Jack Kornfield, Sharon Salzberg, Dipa Ma, and Ruth Denison.

- The Vietnamese Theravāda movement, led by figures such as Ven. Hộ-Tông (Vansarakkhita).[54]

Texts

Pāli Tipiṭaka

According to Kate Crosby, for Theravāda, the Pāli Tipiṭaka, also known as the Pāli Canon is "the highest authority on what constitutes the Dhamma (the truth or teaching of the Buddha) and the organization of the Sangha (the community of monks and nuns)."[55]

The language of the Tipiṭaka, Pāli, is a middle-Indic language which is the main religious and scholarly language in Theravāda. This language may have evolved out of various Indian dialects, and is related to, but not the same as, the ancient language of Magadha.[56]

An early form of the Tipiṭaka may have been transmitted to Sri Lanka during the reign of Ashoka, which saw a period of Buddhist missionary activity. After being orally transmitted (as was the custom for religious texts in those days) for some centuries, the texts were finally committed to writing in the 1st century BCE. Theravāda is one of the first Buddhist schools to commit its Tipiṭaka to writing.[57] The recension of the Tipiṭaka which survives today is that of the Sri Lankan Mahavihara sect.[58]

The oldest manuscripts of the Tipiṭaka from Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia date to the 15th Century, and they are incomplete.[59] Complete manuscripts of the four Nikayas are only available from the 17th Century onwards.[60] However, fragments of the Tipiṭaka have been found in inscriptions from Southeast Asia, the earliest of which have been dated to the 3rd or 4th century.[59][61] According to Alexander Wynne, "they agree almost exactly with extant Pāli manuscripts. This means that the Pāli Tipiṭaka has been transmitted with a high degree of accuracy for well over 1,500 years."[61]

There are numerous editions of the Tipiṭaka, some of the major modern editions include the Pali Text Society edition (published in Roman script), the Burmese Sixth Council edition (in Burmese script, 1954–56) and the Thai Tipiṭaka edited and published in Thai script after the council held during the reign of Rama VII (1925–35). There is also a Khmer edition, published in Phnom Penh (1931–69).[62][63][64]

The Pāli Tipitaka consists of three parts: the Vinaya Pitaka, Sutta Pitaka and Abhidhamma Pitaka. Of these, the Abhidhamma Pitaka is believed to be a later addition to the collection, its composition dating from around the 3rd century BCE onwards.[65] The Pāli Abhidhamma was not recognized outside the Theravāda school. There are also some texts which were late additions that are included in the fifth Nikaya, the Khuddaka Nikāya ('Minor Collection'), such as the Paṭisambhidāmagga (possibly c. 3rd to 1st century BCE) and the Buddhavaṃsa (c. 1st and 2nd century BCE).[66][67]

The main parts of the Sutta Pitaka and some portions of the Vinaya show considerable overlap in content with the Agamas, the parallel collections used by non-Theravāda schools in India which are preserved in Chinese and partially in Sanskrit, Prakrit, and Tibetan, as well as the various non-Theravāda Vinayas. On this basis, these Early Buddhist texts (i.e. the Nikayas and parts of the Vinaya) are generally believed to be some of the oldest and most authoritative sources on the doctrines of pre-sectarian Buddhism by modern scholars.[68][69]

Much of the material in the earlier portions is not specifically "Theravādan", but the collection of teachings that this school's adherents preserved from the early, non-sectarian body of teachings. According to Peter Harvey, while the Theravādans may have added texts to their Tipiṭaka (such as the Abhidhamma texts and so on), they generally did not tamper with the earlier material.[70]

The historically later parts of the canon, mainly the Abhidhamma and some parts of the Vinaya, contain some distinctive elements and teachings which are unique to the Theravāda school and often differ from the Abhidharmas or Vinayas of other early Buddhist schools.[71] For example, while the Theravāda Vinaya contains a total of 227 monastic rules for bhikkhus, the Dharmaguptaka Vinaya (used in East Asian Buddhism) has a total of 253 rules for bhikkhus (though the overall structure is the same).[72] These differences arose from the systematization and historical development of doctrines and monasticism in the centuries after the death of the Buddha.[73]

The Abhidhamma-pitaka contains "a restatement of the doctrine of the Buddha in strictly formalized language." Its texts present a new method, the Abhidhamma method, which attempts to build a single consistent philosophical system (in contrast with the suttas, which present numerous teachings given by the Buddha to particular individuals according to their needs).[74] Because the Abhidhamma focuses on analyzing the internal lived experience of beings and the intentional structure of consciousness, it has often been compared to a kind of phenomenological psychology by numerous modern scholars such as Nyanaponika, Bhikkhu Bodhi and Alexander Piatigorsky.[75]

The Theravāda school has traditionally held the doctrinal position that the canonical Abhidhamma Pitaka was actually taught by the Buddha himself.[76] Modern scholarship in contrast, has generally held that the Abhidhamma texts date from the 3rd century BCE onwards.[77] However some scholars, such as Frauwallner, also hold that the early Abhidhamma texts developed out of exegetical and catechetical work which made use of doctrinal lists which can be seen in the suttas, called matikas.[78][79]

Non-canonical literature

There are numerous Theravāda works which are important for the tradition even though they are not part of the Tipiṭaka. Perhaps the most important texts apart from the Tipiṭaka are the works of the influential scholar Buddhaghosa (4th–5th century CE), known for his Pāli commentaries (which were based on older Sri Lankan commentaries of the Mahavihara tradition). He is also the author of a very important compendium of Theravāda doctrine, the Visuddhimagga.[80] Other figures like Dhammapala and Buddhadatta also wrote Theravāda commentaries and other works in Pali during the time of Buddhaghosa.[81] While these texts do not have the same scriptural authority in Theravāda as the Tipiṭaka, they remain influential works for the exegesis of the Tipiṭaka.

An important genre of Theravādin literature is shorter handbooks and summaries, which serve as introductions and study guides for the larger commentaries. Two of the more influential summaries are Sariputta Thera's Pālimuttakavinayavinicchayasaṅgaha, a summary of Buddhaghosa's Vinaya commentary and Anuruddha's Abhidhammaṭṭhasaṅgaha (a "Manual of Abhidhamma").[82]

Throughout the history of Theravāda, Theravāda monks also produced other works of Pāli literature such as historical chronicles (like the Dipavamsa and the Mahavamsa), hagiographies, poetry, Pāli grammars, and "sub-commentaries" (that is, commentaries on the commentaries).

While Pāli texts are symbolically and ritually important for many Theravādins, most people are likely to access Buddhist teachings through vernacular literature, oral teachings, sermons, art and performance as well as films and Internet media.[83] According to Kate Crosby, "there is a far greater volume of Theravāda literature in vernacular languages than in Pāli."[84]

An important genre of Theravādin literature, in both Pāli and vernacular languages, are the Jataka tales, stories of the Buddha's past lives. They are very popular among all classes and are rendered in a wide variety of media formats, from cartoons to high literature. The Vessantara Jātaka is one of the most popular of these.[85]

Most Theravāda Buddhists generally consider Mahāyāna Buddhist scriptures to be apocryphal, meaning that they are not authentic words of the Buddha.[86]

Doctrine

Core teachings

The core of Theravāda Buddhist doctrine is contained in the Pāli Canon, the only complete collection of Early Buddhist Texts surviving in a classical Indic language.[87] These basic Buddhist ideas are shared by the other Early Buddhist schools as well as by Mahayana traditions. They include central concepts such as:[88]

- A doctrine of action (karma), which is based on intention (cetana) and a related doctrine of rebirth which holds that after death, sentient beings which are not fully awakened will transmigrate to another body, possibly in another realm of existence. The type of realm one will be reborn in is determined by the being's past karma. This cyclical universe filled with birth and death is named samsara.

- A rejection of other doctrines and practices found in Brahmanical Hinduism, including the idea that the Vedas are a divine authority. Any form of sacrifices to the gods (including animal sacrifices) and ritual purification by bathing are considered useless and spiritually corrupted.[89] The Pāli texts also reject the idea that castes are divinely ordained.

- A set of major teachings called the bodhipakkhiyādhammā (factors conducive to awakening).

- Descriptions of various meditative practices or states, namely the four jhanas (meditative absorptions) and the formless dimensions (arupāyatana).

- Ethical training (sila) including the ten courses of wholesome action and the five precepts.

- Nirvana (Pali: nibbana), the highest good and final goal in Theravāda Buddhism. It is the complete and final end of suffering, a state of perfection. It is also the end of all rebirth, but it is not an annihilation (uccheda).[90]

- The corruptions or influxes (āsavas), such as the corruption of sensual pleasures (kāmāsava), existence-corruption (bhavāsava), and ignorance-corruption (avijjāsava).

- The doctrine of impermanence (anicca), which holds that all physical and mental phenomena are transient, unstable and inconstant.[91]

- The doctrine of not-self (anatta), which holds that all the constituents of a person, namely, the five aggregates (physical form, feelings, perceptions, intentions and consciousness), are empty of a self (atta), since they are impermanent and not always under our control. Therefore, there is no unchanging substance, permanent self, soul, or essence.[92][93]

- The Five hindrances (pañca nīvaraṇāni), which are obstacles to meditation: (1) sense desire, (2) hostility, (3) sloth and torpor, (4) restlessness and worry and (5) doubt.

- The Four Divine Abodes (brahmavihārā), also known as the four immeasurables (appamaññā)

- The Four Noble Truths, which state, in brief: (1) There is dukkha (suffering, unease); (2) There is a cause of dukkha, mainly craving (tanha); (3) The removal of craving leads to the end (nirodha) of suffering, and (4) there is a path (magga) to follow to bring this about.[94]

- The framework of Dependent Arising (paṭiccasamuppāda), which explains how suffering arises (beginning with ignorance and ending in birth, old age and death) and how suffering can be brought to an end.[95]

- The Middle Way, which is seen as having two major facets. First, it is a middle path between extreme asceticism and sensual indulgence. It is also seen as a middle view between the idea that at death beings are annihilated and the idea that there is an eternal self (Pali: atta).

- The Noble Eightfold Path, one of the main outlines of the Buddhist path to awakening. The eight factors are: Right View, Right Intention, Right Speech, Right Conduct, Right Livelihood, Right Effort, Right Mindfulness, and Right Samadhi.

- The practice of taking refuge in the "Triple Gems": the Buddha, the Dhamma and the Saṅgha.

- The Seven Aids to Awakening (satta bojjhaṅgā): mindfulness (sati), investigation (dhamma vicaya), energy (viriya), bliss (pīti), relaxation (passaddhi), samādhi, and equanimity (upekkha).

- The six sense bases (saḷāyatana) and a corresponding theory of Sense impression (phassa) and consciousness (viññana).[96]

- Various frameworks for the practice of mindfulness (sati), mainly, the four satipatthanas (establishments of mindfulness) and the 16 elements of anapanasati (mindfulness of breathing).

Abhidhamma philosophy

Theravāda scholastics developed a systematic exposition of the Buddhist doctrine called the Abhidhamma. In the Pāli Nikayas, the Buddha teaches through an analytical method in which experience is explained using various conceptual groupings of physical and mental processes, which are called "dhammas". Examples of lists of dhammas taught by the Buddha include the twelve sense 'spheres' or ayatanas, the five aggregates or khandha and the eighteen elements of cognition or dhatus.[97]

Theravāda traditionally promotes itself as the Vibhajjavāda "teaching of analysis" and as the heirs to the Buddha's analytical method. Expanding this model, Theravāda Abhidhamma scholasticism concerned itself with analyzing "ultimate truth" (paramattha-sacca) which it sees as being composed of all possible dhammas and their relationships. The central theory of the Abhidhamma is thus known as the "dhamma theory".[98][99] "Dhamma" has been translated as "factors" (Collett Cox), "psychic characteristics" (Bronkhorst), "psycho-physical events" (Noa Ronkin) and "phenomena" (Nyanaponika Thera).[100][3]

According to the Sri Lankan scholar Y. Karunadasa, a dhammas ("principles" or "elements") are "those items that result when the process of analysis is taken to its ultimate limits".[98] However, this does not mean that they have an independent existence, for it is "only for the purposes of description" that they are postulated.[101] Noa Ronkin defines dhammas as "the constituents of sentient experience; the irreducible 'building blocks' that make up one's world, albeit they are not static mental contents and certainly not substances."[102] Thus, while in Theravāda Abhidhamma, dhammas are the ultimate constituents of experience, they are not seen as substances, essences or independent particulars, since they are empty (suñña) of a self (attā) and conditioned.[103] This is spelled out in the Patisambhidhamagga, which states that dhammas are empty of svabhava (sabhavena suññam).[104]

According to Ronkin, the canonical Pāli Abhidhamma remains pragmatic and psychological, and "does not take much interest in ontology" in contrast with the Sarvastivada tradition. Paul Williams also notes that the Abhidhamma remains focused on the practicalities of insight meditation and leaves ontology "relatively unexplored".[105] Ronkin does note however that later Theravāda sub-commentaries (ṭīkā) do show a doctrinal shift towards ontological realism from the earlier epistemic and practical concerns.[106]

On the other hand, Y. Karunadasa contends that the tradition of realism goes back to the earliest discourses, as opposed to developing only in later Theravada sub-commentaries:

If we base ourselves on the Pali Nikayas, then we should be compelled to conclude that Buddhism is realistic. There is no explicit denial anywhere of the external world. Nor is there any positive evidence to show that the world is mind-made or simply a projection of subjective thoughts. That Buddhism recognizes the extra-mental existence of matter and, the external world is clearly suggested by the texts. Throughout the discourses it is the language of realism that one encounters. The whole Buddhist practical doctrine and discipline, which has the attainment of Nibbana as its final goal, is based on the recognition of the material world and the conscious living beings living therein.[107]

The Theravāda Abhidhamma holds that there is a total of 82 possible types of dhammas, 81 of these are conditioned (sankhata), while one is unconditioned, which is nibbana. The 81 conditioned dhammas are divided into three broad categories: consciousness (citta), associated mentality (cetasika) and materiality, or physical phenomena (rupa).[108] Since no dhamma exists independently, every single dhamma of consciousness, known as a citta, arises associated (sampayutta) with at least seven mental factors (cetasikas).[109] In Abhidhamma, all awareness events are thus seen as being characterized by intentionality and never exist in isolation.[108] Much of Abhidhamma philosophy deals with categorizing the different consciousnesses and their accompanying mental factors as well as their conditioned relationships (paccaya).[109]

Cosmology

The Pāli Tipiṭaka outlines a hierarchical cosmological system with various planes existence (bhava) into which sentient beings may be reborn depending on their past actions. Good actions lead one to the higher realms, bad actions lead to the lower realms.[110][111] However, even for the gods (devas) in the higher realms like Indra and Vishnu, there is still death, loss and suffering.[112]

The main categories of the planes of existence are:[110][111]

- Arūpa-bhava, the formless or incorporeal plane. These are associated with the four formless meditations, that is: infinite space, infinite consciousness, infinite nothingness and neither perception nor non-perception. Beings in these realms live extremely long lives (thousands of kappas).

- Kāma-bhava, the plane of desires. This includes numerous realms of existence such as: various hells (niraya) which are devoid of happiness, the realms of animals, the hungry ghosts (peta), the realm of humans, and various heaven realms where the devas live (such as Tavatimsa and Tusita).

- Rūpa-bhava, the plane of form. The realms in this plane are associated with the four meditative absorptions (jhanas) and those who attain these meditations are reborn in these divine realms.

These various planes of existence can be found in countless world systems (loka-dhatu), which are born, expand, contract and are destroyed in a cyclical nature across vast expanses of time (measures in kappas). This cosmology is similar to other ancient Indian systems, such as the Jain cosmology.[111] This entire cyclical multiverse of constant birth and death is called samsara. Outside of this system of samsara is nibbana (lit. "vanishing, quenching, blowing out"), a deathless (amata) and transcendent reality, which is a total and final release (vimutti) from all suffering (dukkha) and rebirth.[113]

Soteriology and Buddhology

According to Theravāda doctrine, release from suffering (i.e. nibbana) is attained in four stages of awakening (bodhi):[web 2][web 3]

- Stream-Enterers: Those who have destroyed the first three fetters (the false view of self, doubt/indecision, and clinging to ethics and vows);[web 4][web 5]

- Once-Returners: Those who have destroyed the first three fetters and have weakened the fetters of desire and ill-will;

- Non-Returners: Those who have destroyed the five lower fetters, which bind beings to the world of the senses;[114]

- Arahants (lit. "honorable" or "worthies"): Those who have realized Nibbana and are free from all defilements. They have abandoned all ignorance, craving for existence, restlessness (uddhacca) and subtle pride (māna).[114]

In Theravāda Buddhism, a Buddha is a sentient being who has discovered the path out of samsara by themselves, has reached Nibbana and then makes the path available to others by teaching (known as "turning the wheel of the Dhamma"). A Buddha is also believed to have extraordinary powers and abilities (abhiññā), such as the ability to read minds and fly through the air.[115]

The Theravāda canon depicts Gautama Buddha as being the most recent Buddha in a line of previous Buddhas stretching back for aeons. They also mention the future Buddha, named Metteya.[116] Traditionally, the Theravāda school also rejects the idea that there can be numerous Buddhas active in the world at the same time.[117]

Regarding the question of how a sentient being becomes a Buddha, the Theravāda school also includes a presentation of this path. Indeed, according to Buddhaghosa, there are three main soteriological paths: the path of the Buddhas (buddhayāna); the way of the individual Buddhas (paccekabuddhayāna); and the way of the disciples (sāvakayāna).[118]

However, unlike in Mahayana Buddhism, the Theravāda holds that the Buddha path is not for everyone and that beings on the Buddha path (bodhisattas) are quite rare.[119] While in Mahayana, bodhisattas refers to beings who have developed the wish to become Buddhas, Theravāda (like other early Buddhist schools), defines a bodhisatta as someone who has made a resolution (abhinīhāra) to become a Buddha in front of a living Buddha, and has also received a confirmation from that Buddha that they will reach Buddhahood.[120] Dhammapala's Cariyāpiṭaka is a Theravāda text which focuses on the path of the Buddhas, while the Nidānakathā and the Buddhavaṃsa are also Theravāda texts which discuss the Buddha path.[120]

Main doctrinal differences with other Buddhist traditions

The orthodox standpoints of Theravāda in comparison to other Buddhist schools are presented in the Kathāvatthu ("Points of Controversy"), as well as in other works by later commentators like Buddhaghosa.

Traditionally, the Theravāda maintains the following key doctrinal positions, though not all Theravādins agree with the traditional point of view:[121][122]

- On the philosophy of time, the Theravāda tradition follows philosophical presentism, the view that only present moment phenomena (dhamma) exist, against the eternalist view of the Sarvāstivādin tradition, which held that dhammas exist in all three times – past, present, future.

- The arahant is never a layperson, for they have abandoned the fetters of a layperson, including married life, using money, etc.

- The power (bala) of a Buddha is unique and not common to the disciples (savaka) or arahants.

- Theravāda Abhidhamma holds that a single thought (citta) cannot last as long as a day.

- Theravāda Abhidhamma holds that insight into the four noble truths happens in one moment (khaṇa), rather than gradually (anupubba), as was held by Sarvastivada. The defilements (kilesa) are also abandoned in a single moment, not gradually.[citation needed]

- Theravāda Abhidhamma traditionally rejects the view that there is an intermediate or transitional state (antarabhāva) between rebirths, they hold that rebirth happens instantaneously (in one mind moment).[123] However, as has been noted by various modern scholars like Bhikkhu Sujato, there are canonical passages which support the idea of an intermediate state (such as the Kutuhalasāla Sutta).[124] Some Theravāda scholars (such as Balangoda Ananda Maitreya) have defended the idea of an intermediate state and it is also a very common belief among some monks and laypersons in the Theravāda world (where it is commonly referred to as the gandhabba or antarabhāva).[125]

- Theravāda also does not accept the Mahayana notion that there are two forms of nibbana, an inferior "localized" or "abiding" (pratiṣṭhita) nirvana and a non-abiding (apratiṣṭhita) nirvana. Such a dual nirvana theory is absent in the suttas.[126] According to the Kathāvatthu, there can be no dividing line separating the unconditioned element and there is no superiority or inferiority in the unity of nibbana.[127]

- Theravāda exegetical works consider nibbana to be a real existent, instead of just a conceptual or nominal existent (prajñapti) referring to the mere destruction (khayamatta) of the defilements or non-existence of the five aggregates, as was held by some in the Sautrantika school for example.[128] In Theravāda scholasticism, nibbana is defined as the cessation (nirodha) consisting in non-arising and exists separately from the mere destruction of passion, hatred and delusion.[129]

- Theravāda exegetical works, mental phenomena last for a very short moment or instant (khaṇa), but physical phenomena do not.

- Theravāda holds that the Buddha resided in the human realm (manussa-loka). It rejects the docetic view found in Mahayana, which says that the Buddha's physical body was a mere manifestation, emanation or magical creation (nirmāṇa) of a transcendental being, and thus, that his birth and death a mere show and unreal.[130] Also, the Theravāda school rejects the view that there are currently numerous Buddhas in all directions.

- Theravāda holds that there is a ground level of consciousness called the bhavaṅga, which conditions the rebirth consciousness.

- Theravāda rejects the Pudgalavada doctrine of the pudgala ("person" or "personal entity") as being more than a conceptual designation imputed on the five aggregates.[131][132]

- Theravāda rejects the view of the Lokottaravada schools which held that the all acts done by the Buddha (including all speech, defecation and urination, etc.) were supramundane or transcendental (lokuttara).[133] Also, for Theravāda, a Buddha does not have the power to stop something that has arisen from ceasing, they cannot stop a being from getting old, sick or dying, and they cannot create a permanent thing (like a flower that does not die).

- Theravāda traditionally defends the idea that the Buddha himself taught the Abhidhamma Pitaka.[134] This is now being questioned by some modern Theravādins in light of modern Buddhist studies scholarship.

- In Theravāda, nibbana is the only unconstructed phenomenon (asankhata-dhamma, asankhatadhatu). Unlike in the Sarvāstivāda school, space (akasa), is seen as a constructed dhamma in Theravāda. Even the four noble truths are not unconstructed phenomena, neither is the domain of cessation (nirodhasamapatti). "Thatness" (tathatā) is also a constructed phenomenon. According to the Dhammasangani, nibbana, the unconstructed element, is 'without condition' (appaccaya) and is different from the five aggregates which are 'with condition' (sappaccaya).[135]

- In Theravāda, the bodhisatta path is suitable only for a few exceptional people (like Sakyamuni and Metteya).[136] Theravāda also defines a bodhisatta as someone who has made a vow in front of a living Buddha.[137]

- In Theravāda, there is a physical sensory organ (indriya) that conditions the mental consciousness (manovinñāna) and is the material support for consciousness. Some later Theravāda works like the Visuddhimagga locate this physical basis for consciousness at the heart (hadaya-vatthu), the Pali Canon itself is silent on this issue.[138][139] Some modern Theravāda scholars propose alternative notions. For example, Suwanda H. J. Sugunasiri proposes that the basis for consciousness is the entire physical organism, which he ties with the canonical concept of jīvitindriya or life faculty.[138] W. F. Jayasuriya meanwhile, argues that "hadaya" is not meant literally (it can also mean "essence", "core"), but refers to the entire nervous system (including the brain), which is dependent on the heart and blood.[139] Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Theravadin

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk