A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

The Buddha | |

|---|---|

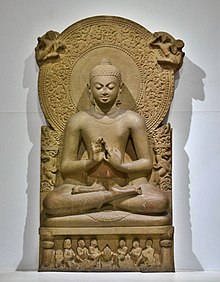

Statue of the Buddha, preaching his first sermon at Sarnath. Gupta period, c. 5th century CE. Archaeological Museum Sarnath (B(b) 181).[a] | |

| Personal | |

| Born | Siddhartha Gautama c. 563 BCE or 480 BCE |

| Died | c. 483 BCE or 400 BCE (aged 80)[1][2][3][c] |

| Resting place | Cremated; ashes divided among followers |

| Spouse | Yashodhara |

| Children | |

| Parents |

|

| Known for | Founding Buddhism |

| Other names | Gautama Buddha Shakyamuni ("Sage of the Shakyas") |

| Senior posting | |

| Predecessor | Kassapa Buddha |

| Successor | Maitreya |

| Sanskrit name | |

| Sanskrit | Siddhārtha Gautama |

| Pali name | |

| Pali | Siddhattha Gotama |

| Part of a series on |

| Buddhism |

|---|

|

Siddhartha Gautama,[e] most commonly referred to as the Buddha ('the awakened'),[f][g] was a wandering ascetic and religious teacher who lived in South Asia during the 6th or 5th century BCE[4][5][6][c] and founded Buddhism. According to Buddhist legends, he was born in Lumbini, in what is now Nepal,[b] to royal parents of the Shakya clan, but renounced his home life to live as a wandering ascetic.[7][h] Buddhists believe that after leading a life of mendicancy, asceticism, and meditation, he attained nirvana at Bodh Gaya in what is now India. The Buddha then wandered through the lower Indo-Gangetic Plain, teaching and building a monastic order. Buddhist tradition holds he died in Kushinagar and reached parinirvana, final nirvana.[note 1]

According to Buddhist tradition, the Buddha taught a Middle Way between sensual indulgence and severe asceticism,[9] leading to freedom from ignorance, craving, rebirth, and suffering. His core teachings are summarized in the Four Noble Truths and the Noble Eightfold Path, a training of the mind that includes ethical training and kindness toward others, and meditative practices such as sense restraint, mindfulness, dhyana (meditation proper) and the concept of dependent origination, emphasizing the impermanent and interconnected nature of all things.

About two centuries after his death, he came to be known by the title Buddha;[10] his teachings were compiled by the Buddhist community in the Vinaya, his codes for monastic practice, and the Sutta Piṭaka, a compilation of teachings based on his discourses. These were passed down in Middle Indo-Aryan dialects through an oral tradition.[11][12] Later generations composed additional texts, such as systematic treatises known as Abhidharma, biographies of the Buddha, collections of stories about his past lives known as Jataka tales, and additional discourses, i.e., the Mahayana sutras.[13][14]

Buddhism spread beyond the Indian subcontinent, evolving into a variety of traditions and practices. The Buddha is recognized in other religious traditions, such as Hinduism, where he is considered an avatar of Vishnu. His legacy is not only encapsulated in religious institutions, but in the iconography and art inspired by his life and teachings, ranging from aniconic symbols to iconic depictions in various cultural styles.

Etymology, names and titles

Siddhārtha Gautama and Buddha Shakyamuni

According to Donald Lopez Jr., "... he tended to be known as either Buddha or Sakyamuni in China, Korea, Japan, and Tibet, and as either Gotama Buddha or Samana Gotama ('the ascetic Gotama') in Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia."[15]

Buddha, "Awakened One" or "Enlightened One",[10][16][f] is the masculine form of budh (बुध् ), "to wake, be awake, observe, heed, attend, learn, become aware of, to know, be conscious again",[17] "to awaken"[18][19] "'to open up' (as does a flower)",[19] "one who has awakened from the deep sleep of ignorance and opened his consciousness to encompass all objects of knowledge".[19] It is not a personal name, but a title for those who have attained bodhi (awakening, enlightenment).[18] Buddhi, the power to "form and retain concepts, reason, discern, judge, comprehend, understand",[17] is the faculty which discerns truth (satya) from falsehood.

The name of his clan was Gautama (Pali: Gotama). His given name, "Siddhārtha" (the Sanskrit form; the Pali rendering is "Siddhattha"; in Tibetan it is "Don grub"; in Chinese "Xidaduo"; in Japanese "Shiddatta/Shittatta"; in Korean "Siltalta") means "He Who Achieves His Goal".[20] The clan name of Gautama means "descendant of Gotama", "Gotama" meaning "one who has the most light",[21] and comes from the fact that Kshatriya clans adopted the names of their house priests.[22][23]

While the term "Buddha" is used in the Agamas and the Pali Canon, the oldest surviving written records of the term "Buddha" is from the middle of the 3rd century BCE, when several Edicts of Ashoka (reigned c. 269–232 BCE) mention the Buddha and Buddhism.[24][25] Ashoka's Lumbini pillar inscription commemorates the Emperor's pilgrimage to Lumbini as the Buddha's birthplace, calling him the Buddha Shakyamuni[i] (Brahmi script: 𑀩𑀼𑀥 𑀲𑀓𑁆𑀬𑀫𑀼𑀦𑀻 Bu-dha Sa-kya-mu-nī, "Buddha, Sage of the Shakyas").[26]

Shakyamuni (Sanskrit: [ɕaːkjɐmʊnɪ]) means "Sage of the Shakyas".[27]

Tathāgata

Tathāgata (Pali; Pali: [tɐˈtʰaːɡɐtɐ]) is a term the Buddha commonly used when referring to himself or other Buddhas in the Pāli Canon.[28] The exact meaning of the term is unknown, but it is often thought to mean either "one who has thus gone" (tathā-gata), "one who has thus come" (tathā-āgata), or sometimes "one who has thus not gone" (tathā-agata). This is interpreted as signifying that the Tathāgata is beyond all coming and going – beyond all transitory phenomena.[29] A tathāgata is "immeasurable", "inscrutable", "hard to fathom", and "not apprehended".[30]

Other epithets

A list of other epithets is commonly seen together in canonical texts and depicts some of his perfected qualities:[31]

- Bhagavato (Bhagavan) – The Blessed one, one of the most used epithets, together with tathāgata[28]

- Sammasambuddho – Perfectly self-awakened

- Vijja-carana-sampano – Endowed with higher knowledge and ideal conduct.

- Sugata – Well-gone or Well-spoken.

- Lokavidu – Knower of the many worlds.

- Anuttaro Purisa-damma-sarathi – Unexcelled trainer of untrained people.

- Satthadeva-Manussanam – Teacher of gods and humans.

- Araham – Worthy of homage. An Arahant is "one with taints destroyed, who has lived the holy life, done what had to be done, laid down the burden, reached the true goal, destroyed the fetters of being, and is completely liberated through final knowledge".

- Jina – Conqueror. Although the term is more commonly used to name an individual who has attained liberation in the religion Jainism, it is also an alternative title for the Buddha.[32]

The Pali Canon also contains numerous other titles and epithets for the Buddha, including: All-seeing, All-transcending sage, Bull among men, The Caravan leader, Dispeller of darkness, The Eye, Foremost of charioteers, Foremost of those who can cross, King of the Dharma (Dharmaraja), Kinsman of the Sun, Helper of the World (Lokanatha), Lion (Siha), Lord of the Dhamma, Of excellent wisdom (Varapañña), Radiant One, Torchbearer of mankind, Unsurpassed doctor and surgeon, Victor in battle, and Wielder of power.[33] Another epithet, used at inscriptions throughout South and Southeast Asia, is Maha sramana, "great sramana" (ascetic, renunciate).

Sources

Historical sources

Pali suttas

On the basis of philological evidence, Indologist and Pāli expert Oskar von Hinüber says that some of the Pāli suttas have retained very archaic place-names, syntax, and historical data from close to the Buddha's lifetime, including the Mahāparinibbāṇa Sutta which contains a detailed account of the Buddha's final days. Hinüber proposes a composition date of no later than 350–320 BCE for this text, which would allow for a "true historical memory" of the events approximately 60 years prior if the Short Chronology for the Buddha's lifetime is accepted (but he also points out that such a text was originally intended more as hagiography than as an exact historical record of events).[34][35]

John S. Strong sees certain biographical fragments in the canonical texts preserved in Pāli, as well as Chinese, Tibetan and Sanskrit as the earliest material. These include texts such as the "Discourse on the Noble Quest" (Ariyapariyesanā-sutta) and its parallels in other languages.[36]

Pillar and rock inscriptions

No written records about Gautama were found from his lifetime or from the one or two centuries thereafter.[24][25][40] But from the middle of the 3rd century BCE, several Edicts of Ashoka (reigned c. 268 to 232 BCE) mention the Buddha and Buddhism.[24][25] Particularly, Ashoka's Lumbini pillar inscription commemorates the Emperor's pilgrimage to Lumbini as the Buddha's birthplace, calling him the Buddha Shakyamuni (Brahmi script: 𑀩𑀼𑀥 𑀲𑀓𑁆𑀬𑀫𑀼𑀦𑀻 Bu-dha Sa-kya-mu-nī, "Buddha, Sage of the Shakyas").[j][37][38] Another one of his edicts (Minor Rock Edict No. 3) mentions the titles of several Dhamma texts (in Buddhism, "dhamma" is another word for "dharma"),[41] establishing the existence of a written Buddhist tradition at least by the time of the Maurya era. These texts may be the precursor of the Pāli Canon.[42][43][k]

"Sakamuni" is also mentioned in a relief of Bharhut, dated to c. 100 BCE, in relation with his illumination and the Bodhi tree, with the inscription Bhagavato Sakamunino Bodho ("The illumination of the Blessed Sakamuni").[44][45]

Oldest surviving manuscripts

The oldest surviving Buddhist manuscripts are the Gandhāran Buddhist texts, found in Gandhara (corresponding to modern northwestern Pakistan and eastern Afghanistan) and written in Gāndhārī, they date from the first century BCE to the third century CE.[46]

Biographical sources

Early canonical sources include the Ariyapariyesana Sutta (MN 26), the Mahāparinibbāṇa Sutta (DN 16), the Mahāsaccaka-sutta (MN 36), the Mahapadana Sutta (DN 14), and the Achariyabhuta Sutta (MN 123), which include selective accounts that may be older, but are not full biographies. The Jātaka tales retell previous lives of Gautama as a bodhisattva, and the first collection of these can be dated among the earliest Buddhist texts.[47] The Mahāpadāna Sutta and Achariyabhuta Sutta both recount miraculous events surrounding Gautama's birth, such as the bodhisattva's descent from the Tuṣita Heaven into his mother's womb.

The sources which present a complete picture of the life of Siddhārtha Gautama are a variety of different, and sometimes conflicting, traditional biographies from a later date. These include the Buddhacarita, Lalitavistara Sūtra, Mahāvastu, and the Nidānakathā.[48] Of these, the Buddhacarita[49][50][51] is the earliest full biography, an epic poem written by the poet Aśvaghoṣa in the first century CE.[52] The Lalitavistara Sūtra is the next oldest biography, a Mahāyāna/Sarvāstivāda biography dating to the 3rd century CE.[53]

The Mahāvastu from the Mahāsāṃghika Lokottaravāda tradition is another major biography, composed incrementally until perhaps the 4th century CE.[53] The Dharmaguptaka biography of the Buddha is the most exhaustive, and is entitled the Abhiniṣkramaṇa Sūtra,[54] and various Chinese translations of this date between the 3rd and 6th century CE. The Nidānakathā is from the Theravada tradition in Sri Lanka and was composed in the 5th century by Buddhaghoṣa.[55]

Historical person

Understanding the historical person

Scholars are hesitant to make claims about the historical facts of the Buddha's life. Most of them accept that the Buddha lived, taught, and founded a monastic order during the Mahajanapada, and during the reign of Bimbisara (his friend, protector, and ruler of the Magadha empire); and died during the early years of the reign of Ajatashatru (who was the successor of Bimbisara) thus making him a younger contemporary of Mahavira, the Jain tirthankara.[56][57]

There is less consensus on the veracity of many details contained in traditional biographies,[58][59] as "Buddhist scholars have mostly given up trying to understand the historical person."[60] The earliest versions of Buddhist biographical texts that we have already contain many supernatural, mythical or legendary elements. In the 19th century some scholars simply omitted these from their accounts of the life, so that "the image projected was of a Buddha who was a rational, socratic teacher—a great person perhaps, but a more or less ordinary human being". More recent scholars tend to see such demythologisers as remythologisers, "creating a Buddha that appealed to them, by eliding one that did not".[61]

Dating

The dates of Gautama's birth and death are uncertain. Within the Eastern Buddhist tradition of China, Vietnam, Korea and Japan, the traditional date for Buddha's death was 949 BCE,[1] but according to the Ka-tan system of the Kalachakra tradition, Buddha's death was about 833 BCE.[62]

Buddhist texts present two chronologies which have been used to date the lifetime of the Buddha.[63] The "long chronology", from Sri Lankese chronicles, states the Buddha was born 298 years before Asoka's coronation and died 218 years before the coronation, thus a lifespan of about 80 years. According to these chronicles, Asoka was crowned in 326 BCE, which gives Buddha's lifespan as 624 – 544 BCE, and are the accepted dates in Sri Lanka and South-East Asia.[63] Alternatively, most scholars who also accept the long chronology but date Asoka's coronation around 268 BCE (based on Greek evidence) put the Buddha's lifespan later at 566 – 486 BCE.[63]

However, the "short chronology", from Indian sources and their Chinese and Tibetan translations, place the Buddha's birth at 180 years before Asoka's coronation and death 100 years before the coronation, still about 80 years. Following the Greek sources of Asoka's coronation as 268 BCE, this dates the Buddha's lifespan even later as 448 – 368 BCE.[63]

Most historians in the early 20th century use the earlier dates of 563 – 483 BCE, differing from the long chronology based on Greek evidence by just three years.[1][64] More recently, there are attempts to put his death midway between the long chronology's 480s BCE and the short chronology's 360s BCE, so circa 410 BCE. At a symposium on this question held in 1988,[65][66][67] the majority of those who presented gave dates within 20 years either side of 400 BCE for the Buddha's death.[1][68][c][73] These alternative chronologies, however, have not been accepted by all historians.[74][75][l]

The dating of Bimbisara and Ajatashatru also depends on the long or short chronology. In the long chrononology, Bimbisara reigned c. 558 – c. 492 BCE, and died 492 BCE,[80][81] while Ajatashatru reigned c. 492 – c. 460 BCE.[82] In the short chronology Bimbisara reigned c. 400 BCE,[83][m] while Ajatashatru died between c. 380 BCE and 330 BCE.[83] According to historian K. T. S. Sarao, a proponent of the Short Chronology wherein the Buddha's lifespan was c.477–397 BCE, it can be estimated that Bimbisara was reigning c.457–405 BCE, and Ajatashatru was reigning c.405–373 BCE.[84]

Historical context

Shakyas

According to the Buddhist tradition, Shakyamuni Buddha was a Shakya, a sub-Himalayan ethnicity and clan of north-eastern region of the Indian subcontinent.[b][n] The Shakya community was on the periphery, both geographically and culturally, of the eastern Indian subcontinent in the 5th century BCE.[85] The community, though describable as a small republic, was probably an oligarchy, with his father as the elected chieftain or oligarch.[85] The Shakyas were widely considered to be non-Vedic (and, hence impure) in Brahminic texts; their origins remain speculative and debated.[86] Bronkhorst terms this culture, which grew alongside Aryavarta without being affected by the flourish of Brahminism, as Greater Magadha.[87]

The Buddha's tribe of origin, the Shakyas, seems to have had non-Vedic religious practices which persist in Buddhism, such as the veneration of trees and sacred groves, and the worship of tree spirits (yakkhas) and serpent beings (nagas). They also seem to have built burial mounds called stupas.[86] Tree veneration remains important in Buddhism today, particularly in the practice of venerating Bodhi trees. Likewise, yakkas and nagas have remained important figures in Buddhist religious practices and mythology.[86]

Shramanas

The Buddha's lifetime coincided with the flourishing of influential śramaṇa schools of thought like Ājīvika, Cārvāka, Jainism, and Ajñana.[88] The Brahmajala Sutta records sixty-two such schools of thought. In this context, a śramaṇa refers to one who labours, toils or exerts themselves (for some higher or religious purpose). It was also the age of influential thinkers like Mahavira,[89] Pūraṇa Kassapa, Makkhali Gosāla, Ajita Kesakambalī, Pakudha Kaccāyana, and Sañjaya Belaṭṭhaputta, as recorded in Samaññaphala Sutta, with whose viewpoints the Buddha must have been acquainted.[90][91][o]

Śāriputra and Moggallāna, two of the foremost disciples of the Buddha, were formerly the foremost disciples of Sañjaya Belaṭṭhaputta, the sceptic.[93] The Pāli canon frequently depicts Buddha engaging in debate with the adherents of rival schools of thought. There is philological evidence to suggest that the two masters, Alara Kalama and Uddaka Rāmaputta, were historical figures and they most probably taught Buddha two different forms of meditative techniques.[94] Thus, Buddha was just one of the many śramaṇa philosophers of that time.[95] In an era where holiness of person was judged by their level of asceticism,[96] Buddha was a reformist within the śramaṇa movement, rather than a reactionary against Vedic Brahminism.[97]

Coningham and Young note that both Jains and Buddhists used stupas, while tree shrines can be found in both Buddhism and Hinduism.[98]

Urban environment and egalitarianism

The rise of Buddhism coincided with the Second Urbanisation, in which the Ganges Basin was settled and cities grew, in which egalitarianism prevailed. According to Thapar, the Buddha's teachings were "also a response to the historical changes of the time, among which were the emergence of the state and the growth of urban centres".[99] While the Buddhist mendicants renounced society, they lived close to the villages and cities, depending for alms-givings on lay supporters.[99]

According to Dyson, the Ganges basin was settled from the north-west and the south-east, as well as from within, "coming together in what is now Bihar (the location of Pataliputra)".[100] The Ganges basin was densely forested, and the population grew when new areas were deforestated and cultivated.[100] The society of the middle Ganges basin lay on "the outer fringe of Aryan cultural influence",[101] and differed significantly from the Aryan society of the western Ganges basin.[102][103] According to Stein and Burton, "the gods of the brahmanical sacrificial cult were not rejected so much as ignored by Buddhists and their contemporaries."[102] Jainism and Buddhism opposed the social stratification of Brahmanism, and their egalitarism prevailed in the cities of the middle Ganges basin.[101] This "allowed Jains and Buddhists to engage in trade more easily than Brahmans, who were forced to follow strict caste prohibitions."[104]

Semi-legendary biography

Nature of traditional depictions

In the earliest Buddhist texts, the nikāyas and āgamas, the Buddha is not depicted as possessing omniscience (sabbaññu)[107] nor is he depicted as being an eternal transcendent (lokottara) being. According to Bhikkhu Analayo, ideas of the Buddha's omniscience (along with an increasing tendency to deify him and his biography) are found only later, in the Mahayana sutras and later Pali commentaries or texts such as the Mahāvastu.[107] In the Sandaka Sutta, the Buddha's disciple Ananda outlines an argument against the claims of teachers who say they are all knowing [108] while in the Tevijjavacchagotta Sutta the Buddha himself states that he has never made a claim to being omniscient, instead he claimed to have the "higher knowledges" (abhijñā).[109] The earliest biographical material from the Pali Nikayas focuses on the Buddha's life as a śramaṇa, his search for enlightenment under various teachers such as Alara Kalama and his forty-five-year career as a teacher.[110]

Traditional biographies of Gautama often include numerous miracles, omens, and supernatural events. The character of the Buddha in these traditional biographies is often that of a fully transcendent (Skt. lokottara) and perfected being who is unencumbered by the mundane world. In the Mahāvastu, over the course of many lives, Gautama is said to have developed supramundane abilities including: a painless birth conceived without intercourse; no need for sleep, food, medicine, or bathing, although engaging in such "in conformity with the world"; omniscience, and the ability to "suppress karma".[111] As noted by Andrew Skilton, the Buddha was often described as being superhuman, including descriptions of him having the 32 major and 80 minor marks of a "great man", and the idea that the Buddha could live for as long as an aeon if he wished (see DN 16).[112]

The ancient Indians were generally unconcerned with chronologies, being more focused on philosophy. Buddhist texts reflect this tendency, providing a clearer picture of what Gautama may have taught than of the dates of the events in his life. These texts contain descriptions of the culture and daily life of ancient India which can be corroborated from the Jain scriptures, and make the Buddha's time the earliest period in Indian history for which significant accounts exist.[113] British author Karen Armstrong writes that although there is very little information that can be considered historically sound, we can be reasonably confident that Siddhārtha Gautama did exist as a historical figure.[114] Michael Carrithers goes further, stating that the most general outline of "birth, maturity, renunciation, search, awakening and liberation, teaching, death" must be true.[115]

Previous lives

Legendary biographies like the Pali Buddhavaṃsa and the Sanskrit Jātakamālā depict the Buddha's (referred to as "bodhisattva" before his awakening) career as spanning hundreds of lifetimes before his last birth as Gautama. Many of these previous lives are narrated in the Jatakas, which consists of 547 stories.[116][117] The format of a Jataka typically begins by telling a story in the present which is then explained by a story of someone's previous life.[118]

Besides imbuing the pre-Buddhist past with a deep karmic history, the Jatakas also serve to explain the bodhisattva's (the Buddha-to-be) path to Buddhahood.[119] In biographies like the Buddhavaṃsa, this path is described as long and arduous, taking "four incalculable ages" (asamkheyyas).[120]

In these legendary biographies, the bodhisattva goes through many different births (animal and human), is inspired by his meeting of past Buddhas, and then makes a series of resolves or vows (pranidhana) to become a Buddha himself. Then he begins to receive predictions by past Buddhas.[121] One of the most popular of these stories is his meeting with Dipankara Buddha, who gives the bodhisattva a prediction of future Buddhahood.[122]

Another theme found in the Pali Jataka Commentary (Jātakaṭṭhakathā) and the Sanskrit Jātakamālā is how the Buddha-to-be had to practice several "perfections" (pāramitā) to reach Buddhahood.[123] The Jatakas also sometimes depict negative actions done in previous lives by the bodhisattva, which explain difficulties he experienced in his final life as Gautama.[124]

Birth and early life

According to the Buddhist tradition, Gautama was born in Lumbini,[125][127] now in modern-day Nepal,[p] and raised in Kapilavastu.[128][q] The exact site of ancient Kapilavastu is unknown.[130] It may have been either Piprahwa, Uttar Pradesh, in present-day India,[131] or Tilaurakot, in present-day Nepal.[132] Both places belonged to the Sakya territory, and are located only 24 kilometres (15 mi) apart.[132][b]

In the mid-3rd century BCE the Emperor Ashoka determined that Lumbini was Gautama's birthplace and thus installed a pillar there with the inscription: "...this is where the Buddha, sage of the Śākyas (Śākyamuni), was born."[133]

According to later biographies such as the Mahavastu and the Lalitavistara, his mother, Maya (Māyādevī), Suddhodana's wife, was a princess from Devdaha, the ancient capital of the Koliya Kingdom (what is now the Rupandehi District of Nepal). Legend has it that, on the night Siddhartha was conceived, Queen Maya dreamt that a white elephant with six white tusks entered her right side,[134][135] and ten months later[136] Siddhartha was born. As was the Shakya tradition, when his mother Queen Maya became pregnant, she left Kapilavastu for her father's kingdom to give birth.

Her son is said to have been born on the way, at Lumbini, in a garden beneath a sal tree. The earliest Buddhist sources state that the Buddha was born to an aristocratic Kshatriya (Pali: khattiya) family called Gotama (Sanskrit: Gautama), who were part of the Shakyas, a tribe of rice-farmers living near the modern border of India and Nepal.[137][129][138][r] His father Śuddhodana was "an elected chief of the Shakya clan",[6] whose capital was Kapilavastu, and who were later annexed by the growing Kingdom of Kosala during the Buddha's lifetime.

The early Buddhist texts contain very little information about the birth and youth of Gotama Buddha.[140][141] Later biographies developed a dramatic narrative about the life of the young Gotama as a prince and his existential troubles.[142] They depict his father Śuddhodana as a hereditary monarch of the Suryavansha (Solar dynasty) of Ikṣvāku (Pāli: Okkāka). This is unlikely, as many scholars think that Śuddhodana was merely a Shakya aristocrat (khattiya), and that the Shakya republic was not a hereditary monarchy.[143][144][145] The more egalitarian gaṇasaṅgha form of government, as a political alternative to Indian monarchies, may have influenced the development of the śramanic Jain and Buddhist sanghas,[s] where monarchies tended toward Vedic Brahmanism.[146]

The day of the Buddha's birth, enlightenment and death is widely celebrated in Theravada countries as Vesak and the day he got conceived as Poson.[147] Buddha's Birthday is called Buddha Purnima in Nepal, Bangladesh, and India as he is believed to have been born on a full moon day.

According to later biographical legends, during the birth celebrations, the hermit seer Asita journeyed from his mountain abode, analyzed the child for the "32 marks of a great man" and then announced that he would either become a great king (chakravartin) or a great religious leader.[148][149] Suddhodana held a naming ceremony on the fifth day and invited eight Brahmin scholars to read the future. All gave similar predictions.[148] Kondañña, the youngest, and later to be the first arhat other than the Buddha, was reputed to be the only one who unequivocally predicted that Siddhartha would become a Buddha.[150]

Early texts suggest that Gautama was not familiar with the dominant religious teachings of his time until he left on his religious quest, which is said to have been motivated by existential concern for the human condition.[151] According to the early Buddhist Texts of several schools, and numerous post-canonical accounts, Gotama had a wife, Yasodhara, and a son, named Rāhula.[152] Besides this, the Buddha in the early texts reports that "I lived a spoilt, a very spoilt life, monks (in my parents' home)."[153]

The legendary biographies like the Lalitavistara also tell stories of young Gotama's great martial skill, which was put to the test in various contests against other Shakyan youths.[154]

Renunciation

While the earliest sources merely depict Gotama seeking a higher spiritual goal and becoming an ascetic or śramaṇa after being disillusioned with lay life, the later legendary biographies tell a more elaborate dramatic story about how he became a mendicant.[142][155]

The earliest accounts of the Buddha's spiritual quest is found in texts such as the Pali Ariyapariyesanā-sutta ("The discourse on the noble quest", MN 26) and its Chinese parallel at MĀ 204.[156] These texts report that what led to Gautama's renunciation was the thought that his life was subject to old age, disease and death and that there might be something better.[157] The early texts also depict the Buddha's explanation for becoming a sramana as follows: "The household life, this place of impurity, is narrow – the samana life is the free open air. It is not easy for a householder to lead the perfected, utterly pure and perfect holy life."[158] MN 26, MĀ 204, the Dharmaguptaka Vinaya and the Mahāvastu all agree that his mother and father opposed his decision and "wept with tearful faces" when he decided to leave.[159][160]

Legendary biographies also tell the story of how Gautama left his palace to see the outside world for the first time and how he was shocked by his encounter with human suffering.[161][162] These depict Gautama's father as shielding him from religious teachings and from knowledge of human suffering, so that he would become a great king instead of a great religious leader.[163] In the Nidanakatha (5th century CE), Gautama is said to have seen an old man. When his charioteer Chandaka explained to him that all people grew old, the prince went on further trips beyond the palace. On these he encountered a diseased man, a decaying corpse, and an ascetic that inspired him.[164][165][166] This story of the "four sights" seems to be adapted from an earlier account in the Digha Nikaya (DN 14.2) which instead depicts the young life of a previous Buddha, Vipassi.[166]

The legendary biographies depict Gautama's departure from his palace as follows. Shortly after seeing the four sights, Gautama woke up at night and saw his female servants lying in unattractive, corpse-like poses, which shocked him.[167] Therefore, he discovered what he would later understand more deeply during his enlightenment: dukkha ("standing unstable", "dissatisfaction"[168][169][170][171]) and the end of dukkha.[172] Moved by all the things he had experienced, he decided to leave the palace in the middle of the night against the will of his father, to live the life of a wandering ascetic.[164]

Accompanied by Chandaka and riding his horse Kanthaka, Gautama leaves the palace, leaving behind his son Rahula and Yaśodhara.[173] He travelled to the river Anomiya, and cut off his hair. Leaving his servant and horse behind, he journeyed into the woods and changed into monk's robes there,[174] though in some other versions of the story, he received the robes from a Brahma deity at Anomiya.[175]

According to the legendary biographies, when the ascetic Gautama first went to Rajagaha (present-day Rajgir) to beg for alms in the streets, King Bimbisara of Magadha learned of his quest, and offered him a share of his kingdom. Gautama rejected the offer but promised to visit his kingdom first, upon attaining enlightenment.[176][177]

Ascetic life and awakening

Majjhima Nikaya 4 mentions that Gautama lived in "remote jungle thickets" during his years of spiritual striving and had to overcome the fear that he felt while living in the forests.[179] The Nikaya-texts narrate that the ascetic Gautama practised under two teachers of yogic meditation.[180][181] According to the Ariyapariyesanā-sutta (MN 26) and its Chinese parallel at MĀ 204, after having mastered the teaching of Ārāḍa Kālāma (Pali: Alara Kalama), who taught a meditation attainment called "the sphere of nothingness", he was asked by Ārāḍa to become an equal leader of their spiritual community.[182][183]

Gautama felt unsatisfied by the practice because it "does not lead to revulsion, to dispassion, to cessation, to calm, to knowledge, to awakening, to Nibbana", and moved on to become a student of Udraka Rāmaputra (Pali: Udaka Ramaputta).[184][185] With him, he achieved high levels of meditative consciousness (called "The Sphere of Neither Perception nor Non-Perception") and was again asked to join his teacher. But, once more, he was not satisfied for the same reasons as before, and moved on.[186]

According to some sutras, after leaving his meditation teachers, Gotama then practiced ascetic techniques.[187][t] The ascetic techniques described in the early texts include very minimal food intake, different forms of breath control, and forceful mind control. The texts report that he became so emaciated that his bones became visible through his skin.[189] The Mahāsaccaka-sutta and most of its parallels agree that after taking asceticism to its extremes, Gautama realized that this had not helped him attain nirvana, and that he needed to regain strength to pursue his goal.[190] One popular story tells of how he accepted milk and rice pudding from a village girl named Sujata.[191]

According to the 身毛喜豎經,[u] his break with asceticism led his five companions to abandon him, since they believed that he had abandoned his search and become undisciplined. At this point, Gautama remembered a previous experience of dhyana ("meditation") he had as a child sitting under a tree while his father worked.[190] This memory leads him to understand that dhyana is the path to liberation, and the texts then depict the Buddha achieving all four dhyanas, followed by the "three higher knowledges" (tevijja),[v] culminating in complete insight into the Four Noble Truths, thereby attaining liberation from samsara, the endless cycle of rebirth.[193][194][195][196][w]

According to the Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta (SN 56),[197] the Tathagata, the term Gautama uses most often to refer to himself, realized "the Middle Way"—a path of moderation away from the extremes of self-indulgence and self-mortification, or the Noble Eightfold Path.[197] In later centuries, Gautama became known as the Buddha or "Awakened One". The title indicates that unlike most people who are "asleep", a Buddha is understood as having "woken up" to the true nature of reality and sees the world 'as it is' (yatha-bhutam).[10] A Buddha has achieved liberation (vimutti), also called Nirvana, which is seen as the extinguishing of the "fires" of desire, hatred, and ignorance, that keep the cycle of suffering and rebirth going.[198]

Following his decision to leave his meditation teachers, MĀ 204 and other parallel early texts report that Gautama sat down with the determination not to get up until full awakening (sammā-sambodhi) had been reached; the Ariyapariyesanā-sutta does not mention "full awakening", but only that he attained nirvana.[199] In Buddhist tradition, this event was said to have occurred under a pipal tree—known as "the Bodhi tree"—in Bodh Gaya, Bihar.[200]

As reported by various texts from the Pali Canon, the Buddha sat for seven days under the bodhi tree "feeling the bliss of deliverance".[201] The Pali texts also report that he continued to meditate and contemplated various aspects of the Dharma while living by the River Nairañjanā, such as Dependent Origination, the Five Spiritual Faculties and suffering (dukkha).[202]

The legendary biographies like the Mahavastu, Nidanakatha and the Lalitavistara depict an attempt by Mara, the ruler of the desire realm, to prevent the Buddha's nirvana. He does so by sending his daughters to seduce the Buddha, by asserting his superiority and by assaulting him with armies of monsters.[203] However the Buddha is unfazed and calls on the earth (or in some versions of the legend, the earth goddess) as witness to his superiority by touching the ground before entering meditation.[204] Other miracles and magical events are also depicted.

First sermon and formation of the saṅgha

According to MN 26, immediately after his awakening, the Buddha hesitated on whether or not he should teach the Dharma to others. He was concerned that humans were overpowered by ignorance, greed, and hatred that it would be difficult for them to recognise the path, which is "subtle, deep and hard to grasp". However, the god Brahmā Sahampati convinced him, arguing that at least some "with little dust in their eyes" will understand it. The Buddha relented and agreed to teach. According to Anālayo, the Chinese parallel to MN 26, MĀ 204, does not contain this story, but this event does appear in other parallel texts, such as in an Ekottarika-āgama discourse, in the Catusparisat-sūtra, and in the Lalitavistara.[199]

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=The_Buddha

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk