A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

Na Gaeil · Na Gàidheil · Ny Gaeil | |

|---|---|

Areas which were linguistically and culturally Gaelic c. 1000 (light green) and c. 1700 (medium green); areas that are Gaelic-speaking in the present day (dark green) | |

| Total population | |

| c. 2.1 million (linguistic grouping) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Ireland | 1,873,997 (linguistic)[1] |

| United Kingdom | 122,518 (linguistic)[2] |

| United States | 27,475 (linguistic)[3] |

| Canada | 9,000 (linguistic)[4] |

| Australia | 2,717 (linguistic)[5] |

| New Zealand | 670 (linguistic) |

| Languages | |

| Gaelic languages (Irish · Scottish Gaelic · Manx · Shelta · Beurla Reagaird) also non-Gaelic English and Scots | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity · Irreligion (historic: Paganism) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Norse-Gaels · Gaelicised Normans · Celtic Britons · Scottish Romani Travellers | |

The Gaels (/ɡeɪlz/ GAYLZ; Irish: Na Gaeil [n̪ˠə ˈɡeːlʲ]; Scottish Gaelic: Na Gàidheil [nə ˈkɛː.al]; Manx: Ny Gaeil [nə ˈɡeːl]) are an ethnolinguistic group[6] native to Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man.[a][10] They are associated with the Gaelic languages: a branch of the Celtic languages comprising Irish, Manx and Scottish Gaelic.

Gaelic language and culture originated in Ireland, extending to Dál Riata in western Scotland. In antiquity, the Gaels traded with the Roman Empire and also raided Roman Britain. In the Middle Ages, Gaelic culture became dominant throughout the rest of Scotland and the Isle of Man. There was also some Gaelic settlement in Wales, as well as cultural influence through Celtic Christianity. In the Viking Age, small numbers of Vikings raided and settled in Gaelic lands, becoming the Norse-Gaels. In the 9th century, Dál Riata and Pictland merged to form the Gaelic Kingdom of Alba. Meanwhile, Gaelic Ireland was made up of several kingdoms, with a High King often claiming lordship over them.

In the 12th century, Anglo-Normans conquered parts of Ireland, while parts of Scotland became Normanized. However, Gaelic culture remained strong throughout Ireland, the Scottish Highlands and Galloway. In the early 17th century, the last Gaelic kingdoms in Ireland fell under English control. James VI and I sought to subdue the Gaels and wipe out their culture;[citation needed] first in the Scottish Highlands via repressive laws such as the Statutes of Iona, and then in Ireland by colonizing Gaelic land with English and Scots-speaking Protestant settlers. In the following centuries Gaelic language was suppressed and mostly supplanted by English. However, it continues to be the main language in Ireland's Gaeltacht and Scotland's Outer Hebrides. The modern descendants of the Gaels have spread throughout the rest of the British Isles, the Americas and Australasia.

Traditional Gaelic society was organised into clans, each with its own territory and king (or chief), elected through tanistry. The Irish were previously pagans who had many gods, venerated the ancestors and believed in an Otherworld. Their four yearly festivals – Samhain, Imbolc, Beltane and Lughnasa – continued to be celebrated into modern times. The Gaels have a strong oral tradition, traditionally maintained by shanachies. Inscription in the ogham alphabet began in the 4th century. The Gaels' conversion to Christianity accompanied the introduction of writing in the Roman alphabet. Irish mythology and Brehon law were preserved and recorded by medieval Irish monasteries.[11] Gaelic monasteries were renowned centres of learning and played a key role in developing Insular art; Gaelic missionaries and scholars were highly influential in western Europe. In the Middle Ages, most Gaels lived in roundhouses and ringforts. The Gaels had their own style of dress, which became the belted plaid and kilt. They also have distinctive music, dance, festivals, and sports. Gaelic culture continues to be a major component of Irish, Scottish and Manx culture.

Ethnonyms

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

Throughout the centuries, Gaels and Gaelic-speakers have been known by a number of names. The most consistent of these have been Gael, Irish and Scots. In Latin, the Gaels were called Scoti,[12] but this later came to mean only the Gaels of Scotland. Other terms, such as Milesian, are not as often used.[13] An Old Norse name for the Gaels was Vestmenn (meaning "Westmen", due to inhabiting the Western fringes of Europe).[14] Informally, archetypal forenames such as Tadhg or Dòmhnall are sometimes used for Gaels.[15]

Gael

The word "Gaelic" is first recorded in print in the English language in the 1770s,[16] replacing the earlier word Gathelik which is attested as far back as 1596.[16] Gael, defined as a "member of the Gaelic race", is first attested in print in 1810.[17] In English, the more antiquarian term Goidels came to be used by some due to Edward Lhuyd's work on the relationship between Celtic languages. This term was further popularised in academia by John Rhys; the first Professor of Celtic at Oxford University; due to his work Celtic Britain (1882).[18]

These names all come from the Old Irish word Goídel/Gaídel. In Early Modern Irish, it was spelled Gaoidheal (singular) and Gaoidheil/Gaoidhil (plural).[19] In modern Irish, it is spelled Gael (singular) and Gaeil (plural). According to scholar John T. Koch, the Old Irish form of the name was borrowed from an Archaic Welsh form Guoidel, meaning "forest people", "wild men" or, later, "warriors".[19] Guoidel is recorded as a personal name in the Book of Llandaff. The root of the name is cognate at the Proto-Celtic level with Old Irish fíad 'wild', and Féni, derived ultimately from Proto-Indo-European *weidh-n-jo-.[19][20] This latter word is the origin of Fianna and Fenian.

In medieval Ireland, the bardic poets who were the cultural intelligentsia of the nation, limited the use of Gaoidheal specifically to those who claimed genealogical descent from the mythical Goídel Glas.[21] Even the Gaelicised Normans who were born in Ireland, spoke Irish and sponsored Gaelic bardic poetry, such as Gearóid Iarla, were referred to as Gall ("foreigner") by Gofraidh Fionn Ó Dálaigh, then Chief Ollam of Ireland.[21]

Irish

A common name, passed down to the modern day, is "Irish"; this existed in the English language during the 11th century in the form of Irisce, which derived from the stem of Old English Iras, "inhabitant of Ireland", from Old Norse irar.[22] The ultimate origin of this word is thought to be the Old Irish Ériu, which is from Old Celtic *Iveriu, likely associated with the Proto-Indo-European term *pi-wer- meaning "fertile".[22] Ériu is mentioned as a goddess in the Lebor Gabála Érenn as a daughter of Ernmas of the Tuatha Dé Danann. Along with her sisters Banba and Fódla, she is said to have made a deal with the Milesians to name the island after her.

The ancient Greeks, in particular Ptolemy in his second century Geographia, possibly based on earlier sources, located a group known as the Iverni (Greek: Ιουερνοι) in the south-west of Ireland.[23] This group has been associated with the Érainn of Irish tradition by T. F. O'Rahilly and others.[23] The Érainn, claiming descent from a Milesian eponymous ancestor named Ailill Érann, were the hegemonic power in Ireland before the rise of the descendants of Conn of the Hundred Battles and Mug Nuadat. The Érainn included peoples such as the Corcu Loígde and Dál Riata. Ancient Roman writers, such as Caesar, Pliny and Tacitus, derived from Ivernia the name Hibernia.[23] Thus the name "Hibernian" also comes from this root, although the Romans tended to call the isle Scotia, and the Gaels Scoti.[24] Within Ireland itself, the term Éireannach (Irish), only gained its modern political significance as a primary denominator from the 17th century onwards, as in the works of Geoffrey Keating, where a Catholic alliance between the native Gaoidheal and Seanghaill ("old foreigners", of Norman descent) was proposed against the Nuaghail or Sacsanach (the ascendant Protestant New English settlers).[21]

Scots

The Scots Gaels derive from the kingdom of Dál Riata, which included parts of western Scotland and northern Ireland. It has various explanations of its origins, including a foundation myth of an invasion from Ireland. Other historians believe that the Gaels colonized parts of Western Scotland over several decades and some archaeological evidence may point to a pre-existing maritime province united by the sea and isolated from the rest of Scotland by the Scottish Highlands or Druim Alban, however, this is disputed.[25][26] The genetical exchange includes passage of the M222 genotype within Scotland.[27]

From the 5th to 10th centuries, early Scotland was home not only to the Gaels of Dál Riata but also the Picts, the Britons, Angles and lastly the Vikings.[28] The Romans began to use the term Scoti to describe the Gaels in Latin from the 4th century onward.[29][30] At the time, the Gaels were raiding the west coast of Britain, and they took part in the Great Conspiracy; it is thus conjectured that the term means "raider, pirate". Although the Dál Riata settled in Argyll in the 6th century, the term "Scots" did not just apply to them, but to Gaels in general. Examples can be taken from Johannes Scotus Eriugena and other figures from Hiberno-Latin culture and the Schottenkloster founded by Irish Gaels in Germanic lands.

The Gaels of northern Britain referred to themselves as Albannaich in their own tongue and their realm as the Kingdom of Alba (founded as a successor kingdom to Dál Riata and Pictland). Germanic groups tended to refer to the Gaels as Scottas[30] and so when Anglo-Saxon influence grew at court with Duncan II, the Latin Rex Scottorum began to be used and the realm was known as Scotland; this process and cultural shift was put into full effect under David I, who let the Normans come to power and furthered the Lowland-Highland divide. Germanic-speakers in Scotland spoke a language called Inglis, which they started to call Scottis (Scots) in the 16th century, while they in turn began to refer to Scottish Gaelic as Erse (meaning "Irish").[31]

Population

Kinship groups

In traditional Gaelic society, a patrilineal kinship group is referred to as a clann[32] or, in Ireland, a fine.[33][34] Both in technical use signify a dynastic grouping descended from a common ancestor, much larger than a personal family, which may also consist of various kindreds and septs. (Fine is not to be confused with the term fian, a 'band of roving men whose principal occupations were hunting and war, also a troop of professional fighting-men under a leader; in wider sense a company, number of persons; a warrior (late and rare)'[35]).

Using the Munster-based Eóganachta as an example, members of this clann claim patrilineal descent from Éogan Mór. It is further divided into major kindreds, such as the Eóganacht Chaisil, Glendamnach, Áine, Locha Léin and Raithlind.[36][37] These kindreds themselves contain septs that have passed down as Irish Gaelic surnames, for example the Eóganacht Chaisil includes O'Callaghan, MacCarthy, O'Sullivan and others.[38][39]

The Irish Gaels can be grouped into the following major historical groups; Connachta (including Uí Néill, Clan Colla, Uí Maine, etc.), Dál gCais, Eóganachta, Érainn (including Dál Riata, Dál Fiatach, etc.), Laigin and Ulaid (including Dál nAraidi). In the Highlands, the various Gaelic-originated clans tended to claim descent from one of the Irish groups, particularly those from Ulster. The Dál Riata (i.e. – MacGregor, MacDuff, MacLaren, etc.) claimed descent from Síl Conairi, for instance.[40] Some arrivals in the High Middle Ages (i.e. – MacNeill, Buchanan, Munro, etc.) claimed to be of the Uí Néill. As part of their self-justification; taking over power from the Norse-Gael MacLeod in the Hebrides; the MacDonalds claimed to be from Clan Colla.[41][42]

For the Irish Gaels, their culture did not survive the conquests and colonisations by the English between 1534 and 1692 (see History of Ireland (1536–1691), Tudor conquest of Ireland, Plantations of Ireland, Cromwellian conquest of Ireland, Williamite War in Ireland. As a result of the Gaelic revival, there has been renewed interest in Irish genealogy; the Irish Government recognised Gaelic Chiefs of the Name since the 1940s.[43] The Finte na hÉireann (Clans of Ireland) was founded in 1989 to gather together clan associations;[44] individual clan associations operate throughout the world and produce journals for their septs.[45] The Highland clans held out until the 18th century Jacobite risings. During the Victorian-era, symbolic tartans, crests and badges were retroactively applied to clans. Clan associations built up over time and Na Fineachan Gàidhealach (The Highland Clans) was founded in 2013.[46]

Human genetics

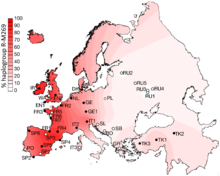

At the turn of the 21st century, the principles of human genetics and genetic genealogy were applied to the study of populations of Irish origin.[47][48] The two other peoples who recorded higher than 85% for R1b in a 2009 study published in the scientific journal, PLOS Biology, were the Welsh and the Basques.[49]

The development of in-depth studies of DNA sequences known as STRs and SNPs have allowed geneticists to associate subclades with specific Gaelic kindred groupings (and their surnames), vindicating significant elements of Gaelic genealogy, as found in works such as the Leabhar na nGenealach. Examples can be taken from the Uí Néill (i.e. – O'Neill, O'Donnell, Gallagher, etc.), who are associated with R-M222[50] and the Dál gCais (i.e. – O'Brien, McMahon, Kennedy, etc.) who are associated with R-L226.[51] With regard to Gaelic genetic genealogy studies, these developments in subclades have aided people in finding their original clan group in the case of a non-paternity event, with Family Tree DNA having the largest such database at present.[52]

In 2016, a study analyzing ancient DNA found Bronze Age remains from Rathlin Island in Ireland to be most genetically similar to the modern indigenous populations of Ireland, Scotland and Wales, and to a lesser degree that of England. The majority of the genomes of the insular Celts would therefore have emerged by 4,000 years ago. It was also suggested that the arrival of proto-Celtic language, possibly ancestral to Gaelic languages, may have occurred around this time.[10] Several genetic traits found at maximum or very high frequencies in the modern populations of Gaelic ancestry were also observed in the Bronze Age period. These traits include a hereditary disease known as HFE hereditary haemochromatosis, Y-DNA Haplogroup R-M269, lactase persistence and blue eyes.[10][53] Another trait very common in Gaelic populations is red hair, with 10% of Irish and at least 13% of Scots having red hair, much larger numbers being carriers of variants of the MC1R gene, and which is possibly related to an adaptation to the cloudy conditions of the regional climate.[10][54][55]

Demographics

In countries where Gaels live, census records documenting population statistics exist. The following chart shows the number of speakers of the Gaelic languages (Irish, Scottish Gaelic, or Manx). The question of ethnic identity is slightly more complex, but included below are those who identify as ethnic Irish, Manx or Scottish. It should be taken into account that not all are of Gaelic descent, especially in the case of Scotland, due to the nature of the Lowlands. It also depends on the self-reported response of the individual and so is a rough guide rather than an exact science.

The two comparatively "major" Gaelic nations in the modern era are Ireland (which had 71,968 "daily" Irish speakers and 1,873,997 people claiming "some ability of Irish", as of the 2022 census)[56] and Scotland (58,552 fluent "Gaelic speakers" and 92,400 with "some Gaelic language ability" in the 2001 census).[57] Communities where the languages still are spoken natively are restricted largely to the west coast of each country and especially the Hebrides islands in Scotland. However, a large proportion of the Gaelic-speaking population now lives in the cities of Glasgow and Edinburgh in Scotland, and Dublin, Cork as well as Counties Donegal and Galway in Ireland. There are about 2,000 Scottish Gaelic speakers in Canada (Canadian Gaelic dialect), although many are elderly and concentrated in Nova Scotia and more specifically Cape Breton Island.[58] According to the U.S. Census in 2000,[3] there are more than 25,000 Irish-speakers in the United States, with the majority found in urban areas with large Irish-American communities such as Boston, New York City and Chicago.

| State | Gaeilge | Ethnic Irish | Gàidhlig | Ethnic Scots | Gaelg | Ethnic Manx |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ireland | 1,873,997 (2022)[56] | 3,969,319 (2011) | not recorded | not recorded | not recorded | not recorded |

| United Kingdom and dependencies | 64,916 (2011)[2] | 1,101,994 (2011)[2][59] | 57,602 (2011) | 4,446,000 (2011) | 1,689 (2000)[60] | 38,108 (2011) |

| United States | 25,870 (2000)[3] | 33,348,049 (2013)[61] | 1,605 (2000)[3] | 5,310,285 (2013)[61] | not recorded | 6,955 |

| Canada | 7,500 (2011)[4] | 4,354,155 (2006)[62] | 1,500 (2011)[4] | 4,719,850 (2006)[62] | not recorded | 4,725 |

| Australia | 1,895 (2011)[5] | 2,087,800 (2011)[63] | 822 (2001) | 1,876,560 (2011) | not recorded | 46,000 |

| New Zealand | not recorded | 14,000 (2013)[64] | 670 (2006) | 12,792 (2006) | not recorded | not recorded |

| Total | 1,974,178 | 44,875,317 | 62,199 | 16,318,487 | 1,689 | 95,788 |

Diaspora

As the Western Roman Empire began to collapse, the Irish (along with the Anglo-Saxons) were one of the peoples able to take advantage in Great Britain from the 4th century onwards. The proto-Eóganachta Uí Liatháin and the Déisi Muman of Dyfed both established colonies in today's Wales. Further to the north, the Érainn's Dál Riata colonised Argyll (eventually founding Alba) and there was a significant Gaelic influence in Northumbria[65] and the MacAngus clan arose to the Pictish kingship by the 8th century. Gaelic Christian missionaries were also active across the Frankish Empire. With the coming of the Viking Age and their slave markets, Irish were also dispersed in this way across the realms under Viking control; as a legacy, in genetic studies, Icelanders exhibit high levels of Gaelic-derived mDNA.[66]

Since the fall of Gaelic polities, the Gaels have made their way across parts of the world, successively under the auspices of the Spanish Empire, French Empire, and the British Empire. Their main destinations were Iberia, France, the West Indies, North America (what is today the United States and Canada) and Oceania (Australia and New Zealand). There has also been a mass "internal migration" within Ireland and Britain from the 19th century, with Irish and Scots migrating to the English-speaking industrial cities of London, Dublin, Glasgow, Liverpool, Manchester, Birmingham, Cardiff, Leeds, Edinburgh and others. Many underwent a linguistic "Anglicisation" and eventually merged with Anglo populations.

In a more narrow interpretation of the term Gaelic diaspora, it could be interpreted as referring to the Gaelic-speaking minority among the Irish, Scottish, and Manx diaspora. However, the use of the term "diaspora" in relation to the Gaelic languages (i.e., in a narrowly linguistic rather than a more broadly cultural context) is arguably not appropriate, as it may suggest that Gaelic speakers and people interested in Gaelic necessarily have Gaelic ancestry, or that people with such ancestry naturally have an interest or fluency in their ancestral language. Research shows that this assumption is inaccurate.[67]

History

Origin legends

In their own national epic contained within medieval works such as the Lebor Gabála Érenn, the Gaels trace the origin of their people to an eponymous ancestor named Goídel Glas. He is described as a Scythian prince (the grandson of Fénius Farsaid), who is credited with creating the Gaelic languages. Goídel's mother is called Scota, described as an Egyptian princess. The Gaels are depicted as wandering from place to place for hundreds of years; they spend time in Egypt, Crete, Scythia, the Caspian Sea and Getulia, before arriving in Iberia, where their king, Breogán, is said to have founded Galicia.[13]

The Gaels are then said to have sailed to Ireland via Galicia in the form of the Milesians, sons of Míl Espáine.[13] The Gaels fight a battle of sorcery with the Tuatha Dé Danann, the gods, who inhabited Ireland at the time. Ériu, a goddess of the land, promises the Gaels that Ireland shall be theirs so long as they pay tribute to her. They agree, and their bard Amergin recites an incantation known as the Song of Amergin. The two groups agree to divide Ireland between them: the Gaels take the world above, while the Tuath Dé take the world below (i.e. the Otherworld).

Ancient

During the Iron Age there was heightened activity at a number of important royal ceremonial sites, including Tara, Dún Ailinne, Rathcroghan and Emain Macha.[68] Each was associated with a Gaelic tribe. The most important was Tara, where the High King (also known as the King of Tara) was inaugurated on the Lia Fáil (Stone of Destiny), which stands to this day.

According to medieval Irish legend, High King Túathal Techtmar was exiled to Roman Britain before returning to claim Tara. Based on the accounts of Tacitus, some modern historians associate him with an "Irish prince" said to have been entertained by Agricola, Governor of Britain, and speculate at Roman sponsorship.[69] His grandson, Conn Cétchathach, is the ancestor of the Connachta who would dominate the Irish Middle Ages. They gained control of what would now be named Connacht. Their close relatives the Érainn (both groups descend from Óengus Tuirmech Temrach) and the Ulaid would later lose out to them in Ulster, as the descendants of the Three Collas in Airgíalla and Niall Noígíallach in Ailech extended their hegemony.[70]

The Gaels emerged into the clear historical record during the classical era, with ogham inscriptions and quite detailed references in Greco-Roman ethnography (most notably by Ptolemy). The Roman Empire conquered most of Britain in the 1st century, but did not conquer Ireland or the far north of Britain. The Gaels had relations with the Roman world, mostly through trade. Roman jewellery and coins have been found at several Irish royal sites, for example.[71] Gaels, known to the Romans as Scoti, also carried out raids on Roman Britain, together with the Picts. These raids increased in the 4th century, as Roman rule in Britain began to collapse.[71] This era was also marked by a Gaelic presence in Britain; in what is today Wales, the Déisi founded the Kingdom of Dyfed and the Uí Liatháin founded Brycheiniog.[72] There was also some Irish settlement in Cornwall.[71] To the north, the Dál Riata are held to have established a territory in Argyll and the Hebrides.[c]

Medieval

Christianity reached Ireland during the 5th century, most famously through a Romano-British slave Patrick,[73] but also through Gaels such as Declán, Finnian and the Twelve Apostles of Ireland. The abbot and the monk eventually took over certain cultural roles of the aos dána (not least the roles of druí and seanchaí) as the oral culture of the Gaels was transmitted to script by the arrival of literacy. Thus Christianity in Ireland during this early time retained elements of Gaelic culture.[73]

In the Middle Ages, Gaelic Ireland was divided into a hierarchy of territories ruled by a hierarchy of kings or chiefs. The smallest territory was the túath (plural: túatha), which was typically the territory of a single kin-group. Several túatha formed a mór túath (overkingdom), which was ruled by an overking. Several overkingdoms formed a cóiced (province), which was ruled by a provincial king. In the early Middle Ages the túath was the main political unit, but during the following centuries the overkings and provincial kings became ever more powerful.[74][75] By the 6th century, the division of Ireland into two spheres of influence (Leath Cuinn and Leath Moga) was largely a reality. In the south, the influence of the Eóganachta based at Cashel grew further, to the detriment of Érainn clans such as the Corcu Loígde and Clann Conla. Through their vassals the Déisi (descended from Fiacha Suidhe and later known as the Dál gCais), Munster was extended north of the River Shannon, laying the foundations for Thomond.[76] Aside from their gains in Ulster (excluding the Érainn's Ulaid), the Uí Néill's southern branch had also pushed down into Mide and Brega. By the 9th century, some of the most powerful kings were being acknowledged as High King of Ireland.

Some, particularly champions of Christianity, hold the 6th to 9th centuries to be a Golden Age for the Gaels. This is due to the influence which the Gaels had across Western Europe as part of their Christian missionary activities. Similar to the Desert Fathers, Gaelic monastics were known for their asceticism.[77] Some of the most celebrated figures of this time were Columba, Aidan, Columbanus and others.[77] Learned in Greek and Latin during an age of cultural collapse,[78] the Gaelic scholars were able to gain a presence at the court of the Carolingian Frankish Empire; perhaps the best known example is Johannes Scotus Eriugena.[79] Aside from their activities abroad, insular art flourished domestically, with artifacts such as the Book of Kells and Tara Brooch surviving. Clonmacnoise, Glendalough, Clonard, Durrow and Inis Cathaigh are some of the more prominent Ireland-based monasteries founded during this time.

There is some evidence in early Icelandic sagas such as the Íslendingabók that the Gaels may have visited the Faroe Islands and Iceland before the Norse, and that Gaelic monks known as papar (meaning father) lived there before being driven out by the incoming Norsemen.[80]

The late 8th century heralded outside involvement in Gaelic affairs, as Norsemen from Scandinavia, known as the Vikings, began to raid and pillage settlements. The earliest recorded raids were on Rathlin and Iona in 795; these hit and run attacks continued for some time until the Norsemen began to settle in the 840s at Dublin (setting up a large slave market), Limerick, Waterford and elsewhere. The Norsemen also took most of the Hebrides and the Isle of Man from the Dál Riata clans and established the Kingdom of the Isles.

The monarchy of Pictland had kings of Gaelic origin, since the 7th century with Bruide mac Der-Ilei, around the times of the Cáin Adomnáin. However, Pictland remained a separate realm from Dál Riata, until the latter gained full hegemony during the reign of Kenneth MacAlpin from the House of Alpin, whereby Dál Riata and Pictland were merged to form the Kingdom of Alba. This meant an acceleration of Gaelicisation in the northern part of Great Britain. The Battle of Brunanburh in 937 defined the Anglo-Saxon Kingdom of England as the hegemonic force in Great Britain, over a Gaelic-Viking alliance.[81]

After a spell when the Norsemen were driven from Dublin by Leinsterman Cerball mac Muirecáin, they returned in the reign of Niall Glúndub, heralding a second Viking period. The Dublin Norse—some of them, such as Uí Ímair king Ragnall ua Ímair now partly Gaelicised as the Norse-Gaels—were a serious regional power, with territories across Northumbria and York. At the same time, the Uí Néill branches were involved in an internal power struggle for hegemony between the northern or southern branches. Donnchad Donn raided Munster and took Cellachán Caisil of the Eóganachta hostage. The destabilisation led to the rise of the Dál gCais and Brian Bóruma. Through military might, Brian went about building a Gaelic Imperium under his High Kingship, even gaining the submission of Máel Sechnaill mac Domnaill. They were involved in a series of battles against the Vikings: Tara, Glenmama and Clontarf. The last of these saw Brian's death in 1014. Brian's campaign is glorified in the Cogad Gáedel re Gallaib ("The War of the Gaels with the Foreigners").

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Scots_Gaels

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk