A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

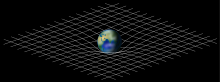

| General relativity |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Physical cosmology |

|---|

| Special relativity |

|---|

|

In physics, a redshift is an increase in the wavelength, and corresponding decrease in the frequency and photon energy, of electromagnetic radiation (such as light). The opposite change, a decrease in wavelength and increase in frequency and energy, is known as a blueshift, or negative redshift. The terms derive from the colours red and blue which form the extremes of the visible light spectrum. The main causes of electromagnetic redshift in astronomy and cosmology are the relative motions of radiation sources, which give rise to the relativistic Doppler effect, and gravitational potentials, which gravitationally redshift escaping radiation. All sufficiently distant light sources show cosmological redshift corresponding to recession speeds proportional to their distances from Earth, a fact known as Hubble's law that implies the universe is expanding.

All redshifts can be understood under the umbrella of frame transformation laws. Gravitational waves, which also travel at the speed of light, are subject to the same redshift phenomena. The value of a redshift is often denoted by the letter z, corresponding to the fractional change in wavelength (positive for redshifts, negative for blueshifts), and by the wavelength ratio 1 + z (which is greater than 1 for redshifts and less than 1 for blueshifts).

Examples of strong redshifting are a gamma ray perceived as an X-ray, or initially visible light perceived as radio waves. Subtler redshifts are seen in the spectroscopic observations of astronomical objects, and are used in terrestrial technologies such as Doppler radar and radar guns.

Other physical processes exist that can lead to a shift in the frequency of electromagnetic radiation, including scattering and optical effects; however, the resulting changes are distinguishable from (astronomical) redshift and are not generally referred to as such (see section on physical optics and radiative transfer).

History

The history of the subject began with the development in the 19th century of classical wave mechanics and the exploration of phenomena associated with the Doppler effect. The effect is named after Christian Doppler, who offered the first known physical explanation for the phenomenon in 1842.[1] The hypothesis was tested and confirmed for sound waves by the Dutch scientist Christophorus Buys Ballot in 1845.[2] Doppler correctly predicted that the phenomenon should apply to all waves, and in particular suggested that the varying colors of stars could be attributed to their motion with respect to the Earth.[3] Before this was verified, it was found that stellar colors were primarily due to a star's temperature, not motion. Only later was Doppler vindicated by verified redshift observations.[citation needed]

The first Doppler redshift was described by French physicist Hippolyte Fizeau in 1848, who pointed to the shift in spectral lines seen in stars as being due to the Doppler effect. The effect is sometimes called the "Doppler–Fizeau effect". In 1868, British astronomer William Huggins was the first to determine the velocity of a star moving away from the Earth by this method.[4] In 1871, optical redshift was confirmed when the phenomenon was observed in Fraunhofer lines using solar rotation, about 0.1 Å in the red.[5] In 1887, Vogel and Scheiner discovered the annual Doppler effect, the yearly change in the Doppler shift of stars located near the ecliptic due to the orbital velocity of the Earth.[6] In 1901, Aristarkh Belopolsky verified optical redshift in the laboratory using a system of rotating mirrors.[7]

Arthur Eddington used the term red shift as early as 1923.[8][9] The word does not appear unhyphenated until about 1934 by Willem de Sitter.[10]

Beginning with observations in 1912, Vesto Slipher discovered that most spiral galaxies, then mostly thought to be spiral nebulae, had considerable redshifts. Slipher first reports on his measurement in the inaugural volume of the Lowell Observatory Bulletin.[11] Three years later, he wrote a review in the journal Popular Astronomy.[12] In it he states that "the early discovery that the great Andromeda spiral had the quite exceptional velocity of –300 km(/s) showed the means then available, capable of investigating not only the spectra of the spirals but their velocities as well."[13]

Slipher reported the velocities for 15 spiral nebulae spread across the entire celestial sphere, all but three having observable "positive" (that is recessional) velocities. Subsequently, Edwin Hubble discovered an approximate relationship between the redshifts of such "nebulae" and the distances to them with the formulation of his eponymous Hubble's law.[14] Milton Humason worked on these observations with Hubble.[15] These observations corroborated Alexander Friedmann's 1922 work, in which he derived the Friedmann–Lemaître equations.[16] In the present day they are considered strong evidence for an expanding universe and the Big Bang theory.[17]

Measurement, characterization, and interpretation

The spectrum of light that comes from a source (see idealized spectrum illustration top-right) can be measured. To determine the redshift, one searches for features in the spectrum such as absorption lines, emission lines, or other variations in light intensity. If found, these features can be compared with known features in the spectrum of various chemical compounds found in experiments where that compound is located on Earth. A very common atomic element in space is hydrogen.

The spectrum of originally featureless light shone through hydrogen will show a signature spectrum specific to hydrogen that has features at regular intervals. If restricted to absorption lines it would look similar to the illustration (top right). If the same pattern of intervals is seen in an observed spectrum from a distant source but occurring at shifted wavelengths, it can be identified as hydrogen too. If the same spectral line is identified in both spectra—but at different wavelengths—then the redshift can be calculated using the table below.

Determining the redshift of an object in this way requires a frequency or wavelength range. In order to calculate the redshift, one has to know the wavelength of the emitted light in the rest frame of the source: in other words, the wavelength that would be measured by an observer located adjacent to and comoving with the source. Since in astronomical applications this measurement cannot be done directly, because that would require traveling to the distant star of interest, the method using spectral lines described here is used instead. Redshifts cannot be calculated by looking at unidentified features whose rest-frame frequency is unknown, or with a spectrum that is featureless or white noise (random fluctuations in a spectrum).[19]

Redshift (and blueshift) may be characterized by the relative difference between the observed and emitted wavelengths (or frequency) of an object. In astronomy, it is customary to refer to this change using a dimensionless quantity called z. If λ represents wavelength and f represents frequency (note, λf = c where c is the speed of light), then z is defined by the equations:[20]

| Based on wavelength | Based on frequency |

|---|---|

After z is measured, the distinction between redshift and blueshift is simply a matter of whether z is positive or negative. For example, Doppler effect blueshifts (z < 0) are associated with objects approaching (moving closer to) the observer with the light shifting to greater energies. Conversely, Doppler effect redshifts (z > 0) are associated with objects receding (moving away) from the observer with the light shifting to lower energies. Likewise, gravitational blueshifts are associated with light emitted from a source residing within a weaker gravitational field as observed from within a stronger gravitational field, while gravitational redshifting implies the opposite conditions.

Redshift formulae

In general relativity one can derive several important special-case formulae for redshift in certain special spacetime geometries, as summarized in the following table. In all cases the magnitude of the shift (the value of z) is independent of the wavelength.[21]

| Redshift type | Geometry | Formula[22] |

|---|---|---|

| Relativistic Doppler | Minkowski space (flat spacetime) |

For motion completely in the radial or

|