A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ɒksiˈkoʊdoʊn/ |

| Trade names | OxyContin, Endone, others |

| Other names | Eukodal, eucodal; dihydrohydroxycodeinone, 7,8-dihydro-14-hydroxycodeinone, 6-deoxy-7,8-dihydro-14-hydroxy-3-O-methyl-6-oxomorphine[1] |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682132 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Dependence liability | High[3] |

| Addiction liability | High[4] |

| Routes of administration | By mouth, sublingual, intramuscular, intravenous, intranasal, subcutaneous, transdermal, rectal, epidural[5] |

| Drug class | Opioid |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | By mouth: 60–87%[7][8] |

| Protein binding | 45%[7] |

| Metabolism | Liver: mainly CYP3A, and, to a much lesser extent, CYP2D6 (~5%);[7] 95% metabolized (i.e., 5% excreted unchanged)[10] |

| Metabolites | • Noroxycodone (25%)[9][10] • Noroxymorphone (15%, free and conjugated)[9][10] • Oxymorphone (11%, conjugated)[9][10] • Others (e.g., minor metabolites)[10] |

| Onset of action | IR: 10–30 minutes[8][10] CR: 1 hour[11] |

| Elimination half-life | By mouth (IR): 2–3 hrs (same t1/2 for all ROAs)[10][8] By mouth (CR): 4.5 hrs[12] |

| Duration of action | By mouth (IR): 3–6 hrs[10] By mouth (CR): 10–12 hrs[13] |

| Excretion | Urine (83%)[7] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.874 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

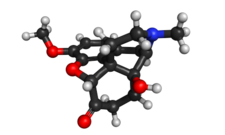

| Formula | C18H21NO4 |

| Molar mass | 315.369 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 219 °C (426 °F) |

| Solubility in water | 166 (HCl) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Oxycodone, sold under various brand names such as Roxicodone and OxyContin (which is the extended release form), is a semi-synthetic opioid used medically for treatment of moderate to severe pain. It is highly addictive[14] and is a commonly abused drug.[15][16] It is usually taken by mouth, and is available in immediate-release and controlled-release formulations.[15] Onset of pain relief typically begins within fifteen minutes and lasts for up to six hours with the immediate-release formulation.[15] In the United Kingdom, it is available by injection.[17] Combination products are also available with paracetamol (acetaminophen), ibuprofen, naloxone, naltrexone, and aspirin.[15]

Common side effects include euphoria, constipation, nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, drowsiness, dizziness, itching, dry mouth, and sweating.[15] Side effects may also include addiction and dependence, substance abuse, irritability, depression or mania, delirium, hallucinations, hypoventilation, gastroparesis, bradycardia, and hypotension.[15] Those allergic to codeine may also be allergic to oxycodone.[15] Use of oxycodone in early pregnancy appears relatively safe.[15] Opioid withdrawal may occur if rapidly stopped from withdrawal.[15] Oxycodone acts by activating the μ-opioid receptor.[18] When taken by mouth, it has roughly 1.5 times the effect of the equivalent amount of morphine.[19]

Oxycodone was originally produced from the opium poppy opiate alkaloid thebaine in 1916. It was first used medically in Germany in 1917.[20] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[21] It is available as a generic medication.[15] In 2021, it was the 59th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 11 million prescriptions.[22][23] A number of abuse-deterrent formulations are available, such as in combination with naloxone or naltrexone.[16][24]

Medical uses

Oxycodone is used for managing moderate to severe acute or chronic pain when other treatments are not sufficient.[15] It may improve quality of life in certain types of pain.[25] Numerous studies have been completed, and the appropriate use of this compound does improve the quality of life of patients with long term chronic pain syndromes.[26][27][28]

Oxycodone is available as a controlled-release tablet, intended to be taken every 12 hours.[29] A 2006 review found that controlled-release oxycodone is comparable to immediate-release oxycodone, morphine, and hydromorphone in management of moderate to severe cancer pain, with fewer side effects than morphine. The author concluded that the controlled-release form is a valid alternative to morphine and a first-line treatment for cancer pain.[29] In 2014, the European Association for Palliative Care recommended oxycodone by mouth as a second-line alternative to morphine by mouth for cancer pain.[30]

In children between 11 and 16, the extended release formulation is FDA approved for the relief of cancer pain, trauma pain, or pain due to major surgery (for those already treated with opioids, who can tolerate at least 20 mg per day of oxycodone) - this provides an alternative to Duragesic (fentanyl), the only other extended-release opioid analgesic approved for children.[31]

Oxycodone, in its extended-release form and/or in combination with naloxone, is sometimes used off-label in the treatment of severe and refractory restless legs syndrome.[32]

Available forms

Oxycodone is available in a variety of formulations for by mouth or under the tongue:[8][33][34][35]

- Immediate-release oxycodone (OxyFast, OxyIR, OxyNorm, Roxicodone)

- Controlled-release oxycodone (OxyContin, Xtampza ER) – 10–12 hour duration[13]

- Oxycodone tamper-resistant (OxyContin OTR)[36]

- Immediate-release oxycodone with paracetamol (acetaminophen) (Percocet, Endocet, Roxicet, Tylox)

- Immediate-release oxycodone with aspirin (Endodan, Oxycodan, Percodan, Roxiprin)

- Immediate-release oxycodone with ibuprofen (Combunox)[37]

- Controlled-release oxycodone with naloxone (Targin, Targiniq, Targinact)[38] – 10–12 hour duration[13]

- Controlled-release oxycodone with naltrexone (Troxyca) – 10–12 hour duration[13][39]

In the US, oxycodone is only approved for use by mouth, available as tablets and oral solutions. Parenteral formulations of oxycodone (brand name OxyNorm) are also available in other parts of the world, however, and are widely used in the European Union.[40][41][42] In Spain, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom, oxycodone is approved for intravenous (IV) and intramuscular (IM) use. When first introduced in Germany during World War I, both IV and IM administrations of oxycodone were commonly used for postoperative pain management of Central Powers soldiers.[5]

Side effects

Most common side effects of oxycodone include reduced sensitivity to pain, delayed gastric emptying, euphoria, anxiolysis (a reduction in anxiety), feelings of relaxation, and respiratory depression.[44] Common side effects of oxycodone include constipation (23%), nausea (23%), vomiting (12%), somnolence (23%), dizziness (13%), itching (13%), dry mouth (6%), and sweating (5%).[44][45] Less common side effects (experienced by less than 5% of patients) include loss of appetite, nervousness, abdominal pain, diarrhea, urinary retention, dyspnea, and hiccups.[46]

Most side effects generally become less intense over time, although issues related to constipation are likely to continue for the duration of use.[47] Chronic use of this compound and associated constipation issues can become very serious, and have been implicated in life-threatening bowel perforations,[48] a number of specific medications including naloxegol[49] have been developed to address opioid induced constipation.

Oxycodone in combination with naloxone in managed-release tablets, has been formulated to both deter abuse and reduce opioid-induced constipation.[50]

Dependence and withdrawal

The risk of experiencing severe withdrawal symptoms is high if a patient has become physically dependent and discontinues oxycodone abruptly. Medically, when the drug has been taken regularly over an extended period, it is withdrawn gradually rather than abruptly. People who regularly use oxycodone recreationally or at higher than prescribed doses are at even higher risk of severe withdrawal symptoms. The symptoms of oxycodone withdrawal, as with other opioids, may include "anxiety, panic attack, nausea, insomnia, muscle pain, muscle weakness, fevers, and other flu-like symptoms".[51][52]

Withdrawal symptoms have also been reported in newborns whose mothers had been either injecting or orally taking oxycodone during pregnancy.[53]

Hormone levels

As with other opioids, chronic use of oxycodone (particularly with higher doses) can often cause concurrent hypogonadism (low sex hormone levels).[54][55]

Overdose

In high doses, overdoses, or in some persons not tolerant to opioids, oxycodone can cause shallow breathing, slowed heart rate, cold/clammy skin, pauses in breathing, low blood pressure, constricted pupils, circulatory collapse, respiratory arrest, and death.[46]

In 2011, it was the leading cause of drug-related deaths in the U.S.[56] However, from 2012 onwards, heroin and fentanyl have become more common causes of drug-related deaths.[56]

Oxycodone overdose has also been described to cause spinal cord infarction in high doses and ischemic damage to the brain, due to prolonged hypoxia from suppressed breathing.[57]

Interactions

Oxycodone is metabolized by the enzymes CYP3A4 and CYP2D6. Therefore, its clearance can be altered by inhibitors and inducers of these enzymes, increasing and decreasing half-life, respectively.[41] (For lists of CYP3A4 and CYP2D6 inhibitors and inducers, see here and here, respectively.) Natural genetic variation in these enzymes can also influence the clearance of oxycodone, which may be related to the wide inter-individual variability in its half-life and potency.[41]

Ritonavir or lopinavir/ritonavir greatly increase plasma concentrations of oxycodone in healthy human volunteers due to inhibition of CYP3A4 and CYP2D6.[58] Rifampicin greatly reduces plasma concentrations of oxycodone due to strong induction of CYP3A4.[59] There is also a case report of fosphenytoin, a CYP3A4 inducer, dramatically reducing the analgesic effects of oxycodone in a chronic pain patient.[60] Dosage or medication adjustments may be necessary in each case.[58][59][60]

Pharmacology

This section's equianalgesic table appears to contradict the article Equianalgesic. (October 2023) |

Pharmacodynamics

| Compound | Affinities (Ki) | Ratio | Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOR | DOR | KOR | MOR:DOR:KOR | ||

| Oxycodone | 18 nM | 958 nM | 677 nM | 1:53:38 | [5] |

| Oxymorphone | 0.78 nM | 50 nM | 137 nM | 1:64:176 | [61] |

| Compound | Route | Dose |

|---|---|---|

| Codeine | PO | 200 mg |

| Hydrocodone | PO | 20–30 mg |

| Hydromorphone | PO | 7.5 mg |

| Hydromorphone | IV | 1.5 mg |

| Morphine | PO | 30 mg |

| Morphine | IV | 10 mg |

| Oxycodone | PO | 20 mg |

| Oxycodone | IV | 10 mg |

| Oxymorphone | PO | 10 mg |

| Oxymorphone | IV | 1 mg |

Oxycodone, a semi-synthetic opioid, is a highly selective full agonist of the μ-opioid receptor (MOR).[40][41] This is the main biological target of the endogenous opioid neuropeptide β-endorphin.[18] Oxycodone has low affinity for the δ-opioid receptor (DOR) and the κ-opioid receptor (KOR), where it is an agonist similarly.[40][41] After oxycodone binds to the MOR, a G protein-complex is released, which inhibits the release of neurotransmitters by the cell by decreasing the amount of cAMP produced, closing calcium channels, and opening potassium channels.[65] Opioids like oxycodone are thought to produce their analgesic effects via activation of the MOR in the midbrain periaqueductal gray (PAG) and rostral ventromedial medulla (RVM).[66] Conversely, they are thought to produce reward and addiction via activation of the MOR in the mesolimbic reward pathway, including in the ventral tegmental area, nucleus accumbens, and ventral pallidum.[67][68] Tolerance to the analgesic and rewarding effects of opioids is complex and occurs due to receptor-level tolerance (e.g., MOR downregulation), cellular-level tolerance (e.g., cAMP upregulation), and system-level tolerance (e.g., neural adaptation due to induction of ΔFosB expression).[69]

Taken orally, 20 mg of immediate-release oxycodone is considered to be equivalent in analgesic effect to 30 mg of morphine,[70][71] while extended release oxycodone is considered to be twice as potent as oral morphine.[72]

Similarly to most other opioids, oxycodone increases prolactin secretion, but its influence on testosterone levels is unknown.[40] Unlike morphine, oxycodone lacks immunosuppressive activity (measured by natural killer cell activity and interleukin 2 production in vitro); the clinical relevance of this has not been clarified.[40]

Active metabolites

A few of the metabolites of oxycodone have also been found to be active as MOR agonists, some of which notably have much higher affinity for (as well as higher efficacy at) the MOR in comparison.[73][74][75] Oxymorphone possesses 3- to 5-fold higher affinity for the MOR than does oxycodone,[10] while noroxycodone and noroxymorphone possess one-third of and 3-fold higher affinity for the MOR, respectively,[10][75] and MOR activation is 5- to 10-fold less with noroxycodone but 2-fold higher with noroxymorphone relative to oxycodone.[76] Noroxycodone, noroxymorphone, and oxymorphone also have longer biological half-lives than oxycodone.[73][77]

| Compound | Ki | EC50 | Cmax | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxycodone | 16.0 nM | 343 nM | 23.2 ± 8.6 ng/mL | 236 ± 102 ng/h/mL |

| Oxymorphone | 0.36 nM | 42.8 nM | 0.82 ± 0.85 ng/mL | 12.3 ± 12 ng/h/mL |

| Noroxycodone | 57.1 nM | 1930 nM | 15.2 ± 4.5 ng/mL | 233 ± 102 ng/h/mL |

| Noroxymorphone | 5.69 nM | 167 nM | ND | ND |

| Ki is for diprenorphine displacement. (Note that diprenorphine is a non-selective opioid receptor ligand, so this is not MOR-specific.) EC50 is for hMOR1 GTPyS binding. Cmax and AUC levels are for 20 mg CR oxycodone. | ||||

However, despite the greater in vitro activity of some of its metabolites, it has been determined that oxycodone itself is responsible for 83.0% and 94.8% of its analgesic effect following oral and intravenous administration, respectively.[74] Oxymorphone plays only a minor role, being responsible for 15.8% and 4.5% of the analgesic effect of oxycodone after oral and intravenous administration, respectively.[74] Although the CYP2D6 genotype and the route of administration result in differential rates of oxymorphone formation, the unchanged parent compound remains the major contributor to the overall analgesic effect of oxycodone.[74] In contrast to oxycodone and oxymorphone, noroxycodone and noroxymorphone, while also potent MOR agonists, poorly cross the blood–brain barrier into the central nervous system, and for this reason are only minimally analgesic in comparison.[73][76][74][75]

κ-opioid receptor

In 1997, a group of Australian researchers proposed (based on a study in rats) that oxycodone acts on KORs, unlike morphine, which acts upon MORs.[78] Further research by this group indicated the drug appears to be a high-affinity κ2b-opioid receptor agonist.[79] However, this conclusion has been disputed, primarily on the basis that oxycodone produces effects that are typical of MOR agonists.[80] In 2006, research by a Japanese group suggested the effect of oxycodone is mediated by different receptors in different situations.[81] Specifically in diabetic mice, the KOR appears to be involved in the antinociceptive effects of oxycodone, while in nondiabetic mice, the μ1-opioid receptor seems to be primarily responsible for these effects.[81][82]

Pharmacokinetics

Instant-release absorption profile

Oxycodone can be administered orally, intranasally, via intravenous, intramuscular, or subcutaneous injection, or rectally. The bioavailability of oral administration of oxycodone averages within a range of 60 to 87%, with rectal administration yielding the same results; intranasal varies between individuals with a mean of 46%.[83]

After a dose of conventional (immediate-release) oral oxycodone, the onset of action is 10 to 30 minutes,[10][8] and peak plasma levels of the drug are attained within roughly 30 to 60 minutes;[10][8][73] in contrast, after a dose of OxyContin (an oral controlled-release formulation), peak plasma levels of oxycodone occur in about three hours.[46] The duration of instant-release oxycodone is 3 to 6 hours, although this can be variable depending on the individual.[10]

Distribution

Oxycodone has a volume of distribution of 2.6L/kg,[84] in the blood it is distributed to skeletal muscle, liver, intestinal tract, lungs, spleen, and brain.[46] At equilibrium the unbound concentration in the brain is threefold higher than the unbound concentration in blood.[85] Conventional oral preparations start to reduce pain within 10 to 15 minutes on an empty stomach; in contrast, OxyContin starts to reduce pain within one hour.[15]

Metabolism

The metabolism of oxycodone in humans occurs in the liver mainly via the cytochrome P450 system and is extensive (about 95%) and complex, with many minor pathways and resulting metabolites.[10][86] Around 10% (range 8–14%) of a dose of oxycodone is excreted essentially unchanged (unconjugated or conjugated) in the urine.[10] The major metabolites of oxycodone are noroxycodone (70%), noroxymorphone ("relatively high concentrations"),[44] and oxymorphone (5%).[73][76] The immediate metabolism of oxycodone in humans is as follows:[10][12][87]

- N-Demethylation to noroxycodone predominantly via CYP3A4

- O-Demethylation to oxymorphone predominantly via CYP2D6

- 6-Ketoreduction to 6α- and 6β-oxycodol

- N-Oxidation to oxycodone-N-oxide

In humans, N-demethylation of oxycodone to noroxycodone by CYP3A4 is the major metabolic pathway, accounting for 45% ± 21% of a dose of oxycodone, while O-demethylation of oxycodone into oxymorphone by CYP2D6 and 6-ketoreduction of oxycodone into 6-oxycodols represent relatively minor metabolic pathways, accounting for 11% ± 6% and 8% ± 6% of a dose of oxycodone, respectively.[10][40]

Several of the immediate metabolites of oxycodone are subsequently conjugated with glucuronic acid and excreted in the urine.[10] 6α-Oxycodol and 6β-oxycodol are further metabolized by N-demethylation to nor-6α-oxycodol and nor-6β-oxycodol, respectively, and by N-oxidation to 6α-oxycodol-N-oxide and 6β-oxycodol-N-oxide (which can subsequently be glucuronidated as well).[10][12] Oxymorphone is also further metabolized, as follows:[10][12][87]

- 3-Glucuronidation to oxymorphone-3-glucuronide predominantly via UGT2B7

- 6-Ketoreduction to 6α-oxymorphol and 6β-oxymorphol

- N-Demethylation to noroxymorphone

The first pathway of the above three accounts for 40% of the metabolism of oxymorphone, making oxymorphone-3-glucuronide the main metabolite of oxymorphone, while the latter two pathways account for less than 10% of the metabolism of oxymorphone.[87] After N-demethylation of oxymorphone, noroxymorphone is further glucuronidated to noroxymorphone-3-glucuronide.[87]

Because oxycodone is metabolized by the cytochrome P450 system in the liver, its pharmacokinetics can be influenced by genetic polymorphisms and drug interactions concerning this system, as well as by liver function.[46] Some people are fast metabolizers of oxycodone, while others are slow metabolizers, resulting in polymorphism-dependent alterations in relative analgesia and toxicity.[88][89] While higher CYP2D6 activity increases the effects of oxycodone (owing to increased conversion into oxymorphone), higher CYP3A4 activity has the opposite effect and decreases the effects of oxycodone (owing to increased metabolism into noroxycodone and noroxymorphone).[90] The dose of oxycodone must be reduced in patients with reduced liver function.[91]

Elimination

The clearance of oxycodone is 0.8 L/min.[84] Oxycodone and its metabolites are mainly excreted in urine.[92] Therefore, oxycodone accumulates in patients with kidney impairment.[91] Oxycodone is eliminated in the urine 10% as unchanged oxycodone, 45% ± 21% as N-demethylated metabolites (noroxycodone, noroxymorphone, noroxycodols), 11 ± 6% as O-demethylated metabolites (oxymorphone, oxymorphols), and 8% ± 6% as 6-keto-reduced metabolites (oxycodols).[92][73]

Duration of action

Oxycodone has a half-life of 4.5 hours.[84] It is available as a generic medication.[15] The manufacturer of OxyContin, a controlled-release preparation of oxycodone, Purdue Pharma, claimed in their 1992 patent application that the duration of action of OxyContin is 12 hours in "90% of patients". It has never performed any clinical studies in which OxyContin was given at more frequent intervals. In a separate filing, Purdue claims that controlled-release oxycodone "provides pain relief in said patient for at least 12 hours after administration".[93] However, in 2016 an investigation by the Los Angeles Times found that "the drug wears off hours early in many people", inducing symptoms of opiate withdrawal and intense cravings for OxyContin. One doctor, Lawrence Robbins, told journalists that over 70% of his patients would report that OxyContin would only provide 4–7 hours of relief. Doctors in the 1990s often would switch their patients to a dosing schedule of once every eight hours when they complained that the duration of action for OxyContin was too short to be taken only twice a day.[93][94]

Purdue strongly discouraged the practice: Purdue's medical director Robert Reder wrote to one doctor in 1995 that "OxyContin has been developed for dosing...I request that you not use a dosing regimen." Purdue repeatedly released memos to its sales representatives ordering them to remind doctors not to deviate from a 12-hour dosing schedule. One such memo read, "There is no Q8 dosing with OxyContin... 8-hour dosing needs to be nipped in the bud. NOW!!"[93] The journalists who covered the investigation argued that Purdue Pharma has insisted on a 12-hour duration of action for nearly all patients, despite evidence to the contrary, to protect the reputation of OxyContin as a 12-hour drug and the willingness of health insurance and managed care companies to cover OxyContin despite its high cost relative to generic opiates such as morphine.[93]

Purdue sales representatives were instructed to encourage doctors to write prescriptions for larger 12-hour doses instead of more frequent dosing. An August 1996 memo to Purdue sales representatives in Tennessee entitled "$$$$$$$$$$$$$ It's Bonus Time in the Neighborhood!" reminded the representatives that their commissions would dramatically increase if they were successful in convincing doctors to prescribe larger doses. Los Angeles Times journalists argue using interviews from opioid addiction experts that such high doses of OxyContin spaced 12 hours apart create a combination of agony during opiate withdrawal (lower lows) and a schedule of reinforcement that relieves this agony, fostering addiction.[93]

Chemistryedit

Oxycodone's chemical name is derived from codeine. The chemical structures are very similar, differing only in that

- Oxycodone has a hydroxy group at carbon-14 (codeine has just a hydrogen in its place)

- Oxycodone has a 7,8-dihydro feature. Codeine has a double bond between those two carbons; and

- Oxycodone has a carbonyl group (as in ketones) in place of the hydroxyl group of codeine.

It is also similar to hydrocodone, differing only in that it has a hydroxyl group at carbon-14.[91]

Biosynthesisedit

In terms of biosynthesis, oxycodone has been found naturally in nectar extracts from the orchid family Epipactis helleborine; together along with another opioid: 3-{2-{3-{3-benzyloxypropyl}-3-indol, 7,8-didehydro- 4,5-epoxy-3,6-d-morphinan.[95]

Thodey et al., 2014 introduces a microbial compound manufacturing system for compounds including oxycodone.[96] The Thodey platform produces both natural and semisynthetic opioids including this one.[96] This system uses Saccharomyces cerevisiae with transgenes from Papaver somniferum (the opium poppy) and Pseudomonas putida to turn a thebaine input into other opiates and opioids.[96]

Detection in biological fluidsedit

Oxycodone and/or its major metabolites may be measured in blood or urine to monitor for clearance, non-medical use, confirm a diagnosis of poisoning, or assist in a medicolegal death investigation. Many commercial opiate screening tests cross-react appreciably with oxycodone and its metabolites, but chromatographic techniques can easily distinguish oxycodone from other opiates.[97]

Historyedit

Martin Freund and (Jakob) Edmund Speyer of the University of Frankfurt in Germany published the first synthesis of oxycodone from thebaine in 1916.[98][99] When Freund died, in 1920, Speyer wrote his obituary for the German Chemical Society.[100] Speyer, born to a Jewish family in Frankfurt am Main in 1878, became a victim of the Holocaust. He died on 5 May 1942, the second day of deportations from the Lodz Ghetto; his death was noted in the ghetto's chronicle.[101]

The first clinical use of the drug was documented in 1917, the year after it was first developed.[99][13] It was first introduced to the U.S. market in May 1939. In early 1928, Merck introduced a combination product containing scopolamine, oxycodone, and ephedrine under the German initials for the ingredients SEE, which was later renamed Scophedal (SCOpolamine, ePHEDrine, and eukodAL) in 1942. It was last manufactured in 1987, but can be compounded. This combination is essentially an oxycodone analogue of the morphine-based "twilight sleep", with ephedrine added to reduce circulatory and respiratory effects.[102] The drug became known as the "Miracle Drug of the 1930s" in Continental Europe and elsewhere and it was the Wehrmacht's choice for a battlefield analgesic for a time. The drug was expressly designed to provide what the patent application and package insert referred to as "very deep analgesia and profound and intense euphoria" as well as tranquillisation and anterograde amnesia useful for surgery and battlefield wounding cases. Oxycodone was allegedly chosen over other common opiates for this product because it had been shown to produce less sedation at equianalgesic doses compared to morphine, hydromorphone (Dilaudid), and hydrocodone (Dicodid).[103]

During Operation Himmler, Skophedal was also reportedly injected in massive overdose into the prisoners dressed in Polish Army uniforms in the staged incident on 1 September 1939 which opened the Second World War.[102][104]

The personal notes of Adolf Hitler's physician, Theodor Morell, indicate Hitler received repeated injections of "Eukodal" (oxycodone; produced by Merck) and Scophedal, as well as Dolantin (pethidine) codeine, and morphine less frequently; oxycodone could not be obtained after late January 1945.[105][106]

In the United States, the Controlled Substances Act (CSA) was passed by the United States Congress and signed into law by President Richard Nixon on 27 October 1970.[107] The passing of the CSA resulted in all products containing oxycodone to be classified as a Schedule II controlled substance.[108]

Purdue Pharma, a privately held company based in Stamford, Connecticut, developed the prescription painkiller OxyContin. It was approved by the FDA in 1995 after no long-term studies and no assessment of its addictive capabilities.[109] David Kessler, FDA commissioner at the time, later said of the approval of OxyContin: "No doubt it was a mistake. It was certainly one of the worst medical mistakes, a major mistake."[110] Upon its release in 1995, OxyContin was hailed as a medical breakthrough, a long-lasting narcotic that could help patients with moderate to severe pain. The drug became a blockbuster and has reportedly generated some US$35 billion in revenue for Purdue.[111]

Opioid epidemicedit

Oxycodone, like other opioid analgesics, tends to induce feelings of euphoria, relaxation and reduced anxiety in those who are occasional users.[112] These effects make it one of the most commonly abused pharmaceutical drugs in the United States.[113] The abuse of Oxycodone, as well as related opioids more broadly, is not unique to the United States and is a common drug of abuse globally.[114][115]

United Statesedit

Oxycodone is the most widely recreationally used opioid in America. In the United States, more than 12 million people use opioid drugs recreationally.[116] The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services estimates that about 11 million people in the U.S. consume oxycodone in a non-medical way annually.[117]

Opioids were responsible for 49,000 of the 72,000 drug overdose deaths in the U.S. in 2017.[118] In 2007, about 42,800 emergency room visits occurred due to "episodes" involving oxycodone.[119] In 2008, recreational use of oxycodone and hydrocodone was involved in 14,800 deaths. Some of the cases were due to overdoses of the acetaminophen component, resulting in fatal liver damage.[120]

In September 2013, the FDA released new labeling guidelines for long acting and extended release opioids requiring manufacturers to remove moderate pain as indication for use, instead stating the drug is for "pain severe enough to require daily, around-the-clock, long term opioid treatment".[121] The updated labeling will not restrict physicians from prescribing opioids for moderate pain, as needed.[116]

Reformulated OxyContin is causing some recreational users to change to heroin, which is cheaper and easier to obtain.[122]

Lawsuitsedit

In October 2017, The New Yorker published a story on Mortimer Sackler and Purdue Pharma regarding their ties to the production and manipulation of the oxycodone markets.[111] The article links Raymond and Arthur Sackler's business practices with the rise of direct pharmaceutical marketing and eventually to the rise of addiction to oxycodone in the United States. The article implies that the Sackler family bears some responsibility for the opioid epidemic in the United States.[123] In 2019, The New York Times ran a piece confirming that Richard Sackler, the son of Raymond Sackler, told company officials in 2008 to "measure our performance by Rx's by strength, giving higher measures to higher strengths".[124] This was verified with documents tied to a lawsuit – which was filed by the Massachusetts attorney general, Maura Healey – claiming that Purdue Pharma and members of the Sackler family knew that high doses of OxyContin over long periods would increase the risk of serious side effects, including addiction.[125] Despite Purdue Pharma's proposal for a US$12 billion settlement of the lawsuit, the attorneys general of 23 states, including Massachusetts, rejected the settlement offer in September 2019.[126]

Australiaedit

The non-medical use of oxycodone existed from the early 1970s, but by 2015, 91% of a national sample of injecting drug users in Australia had reported using oxycodone, and 27% had injected it in the last six months.[127]

Canadaedit

Opioid-related deaths in Ontario had increased by 242% from 1969 to 2014.[128] By 2009 in Ontario there were more deaths from oxycodone overdoses than from cocaine overdoses.[129] Deaths from opioid pain relievers had increased from 13.7 deaths per million residents in 1991 to 27.2 deaths per million residents in 2004.[130] The non-medical use of oxycodone in Canada became a problem. Areas where oxycodone is most problematic are Atlantic Canada and Ontario, where its non-medical use is prevalent in rural towns, and in many smaller to medium-sized cities.[131] Oxycodone is also widely available across Western Canada, but methamphetamine and heroin are more serious problems in larger cities, while oxycodone is more common in rural towns. Oxycodone is diverted through doctor shopping, prescription forgery, pharmacy theft, and overprescription.[131][132]

The recent formulations of oxycodone, particularly Purdue Pharma's crush-, chew-, injection- and dissolve-resistant OxyNEO[133] which replaced the banned OxyContin product in Canada in early 2012, have led to a decline in the recreational use of this opiate but have increased the recreational use of the more potent drug fentanyl.[134] According to a Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse study quoted in Maclean's magazine, there were at least 655 fentanyl-related deaths in Canada in a five-year period.[135]

In Alberta, the Blood Tribe police claimed that from the fall of 2014 through January 2015, oxycodone pills or a lethal fake variation referred to as Oxy 80s[136] containing fentanyl made in illegal labs by members of organized crime were responsible for ten deaths on the Blood Reserve, which is located southwest of Lethbridge, Alberta.[137] Province-wide, approximately 120 Albertans died from fentanyl-related overdoses in 2014.[136]

United Kingdomedit

Prescriptions of Oxycodone rose in Scotland by 430% between 2002 and 2008, prompting fears of usage problems that would mirror those of the United States.[138] The first known death due to overdose in the UK occurred in 2002.[139]

Preventive measuresedit

In August 2010, Purdue Pharma reformulated their long-acting oxycodone line, marketed as OxyContin, using a polymer, Intac,[140] to make the pills more difficult to crush or dissolve in water[141] to reduce non-medical use of OxyContin.[142] The FDA approved relabeling the reformulated version as abuse-resistant in April 2013.[143]

Pfizer manufactures a preparation of short-acting oxycodone, marketed as Oxecta, which contains inactive ingredients, referred to as tamper-resistant Aversion Technology.[144] Approved by the FDA in the U.S. in June 2011, the new formulation, while not being able to deter oral recreational use, makes crushing, chewing, snorting, or injecting the opioid impractical because of a change in its chemical properties.[145]

Legal statusedit

Oxycodone is subject to international conventions on narcotic drugs. In addition, oxycodone is subject to national laws that differ by country. The 1931 Convention for Limiting the Manufacture and Regulating the Distribution of Narcotic Drugs of the League of Nations included oxycodone.[146] The 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs of the United Nations, which replaced the 1931 convention, categorized oxycodone in Schedule I.[147] Global restrictions on Schedule I drugs include "limiting exclusively to medical and scientific purposes the production, manufacture, export, import, distribution of, trade in, use and possession of" these drugs; "requiring medical prescriptions for the supply or dispensation of these drugs to individuals"; and "preventing the accumulation" of quantities of these drugs "in excess of those required for the normal conduct of business".[147]

Australiaedit

Oxycodone is in Schedule I (derived from the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs) of the Commonwealth's Narcotic Drugs Act 1967.[148] In addition, it is in Schedule 8 of the Australian Standard for the Uniform Scheduling of Drugs and Poisons ("Poisons Standard"), meaning it is a "controlled drug... which should be available for use but requires restriction of manufacture, supply, distribution, possession and use to reduce abuse, misuse and physical or psychological dependence".[149]

Canadaedit

Oxycodone is a controlled substance under Schedule I of the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act (CDSA).[150]

In February 2012, Ontario passed legislation to allow the expansion of an already existing drug-tracking system for publicly funded drugs to include those that are privately insured. This database will function to identify and monitor patient's attempts to seek prescriptions from multiple doctors or retrieve them from multiple pharmacies. Other provinces have proposed similar legislation, while some, such as Nova Scotia, have legislation already in effect for monitoring prescription drug use. These changes have coincided with other changes in Ontario's legislation to target the misuse of painkillers and high addiction rates to drugs such as oxycodone. As of 29 February 2012, Ontario passed legislation delisting oxycodone from the province's public drug benefit program. This was a first for any province to delist a drug based on addictive properties. The new law prohibits prescriptions for OxyNeo except to certain patients under the Exceptional Access Program including palliative care and in other extenuating circumstances. Patients already prescribed oxycodone will receive coverage for an additional year for OxyNeo, and after that, it will be disallowed unless designated under the exceptional access program.[151]

Much of the legislative activity has stemmed from Purdue Pharma's decision in 2011 to begin a modification of Oxycontin's composition to make it more difficult to crush for snorting or injecting. The new formulation, OxyNeo, is intended to be preventive in this regard and retain its effectiveness as a painkiller. Since introducing its Narcotics Safety and Awareness Act, Ontario has committed to focusing on drug addiction, particularly in the monitoring and identification of problem opioid prescriptions, as well as the education of patients, doctors, and pharmacists.[152] This Act, introduced in 2010, commits to the establishment of a unified database to fulfil this intention.[153] Both the public and medical community have received the legislation positively, though concerns about the ramifications of legal changes have been expressed. Because laws are largely provincially regulated, many speculate a national strategy is needed to prevent smuggling across provincial borders from jurisdictions with looser restrictions.[154]

In 2015, Purdue Pharma's abuse-resistant OxyNEO and six generic versions of OxyContin had been on the Canada-wide approved list for prescriptions since 2012. In June 2015, then federal Minister of Health Rona Ambrose announced that within three years all oxycodone products sold in Canada would need to be tamper-resistant. Some experts warned that the generic product manufacturers may not have the technology to achieve that goal, possibly giving Purdue Pharma a monopoly on this opiate.[155]

Several class-action suits across Canada have been launched against the Purdue group of companies and affiliates. Claimants argue the pharmaceutical manufacturers did not meet a standard of care and were negligent in doing so. These lawsuits reference earlier judgments in the United States, which held that Purdue was liable for wrongful marketing practices and misbranding. Since 2007, the Purdue companies have paid over CAN$650 million in settling litigation or facing criminal fines.

Germanyedit

The drug is in Appendix III of the Narcotics Act (Betäubungsmittelgesetz or BtMG).[156] The law allows only physicians, dentists, and veterinarians to prescribe oxycodone and the federal government to regulate the prescriptions (e.g., by requiring reporting).[156]

Hong Kongedit

Oxycodone is regulated under Part I of Schedule 1 of Hong Kong's Chapter 134 Dangerous Drugs Ordinance.[157]

Japanedit

Oxycodone is a restricted drug in Japan. Its import and export are strictly restricted to specially designated organizations having a prior permit to import it. In a high-profile case an American who was a top Toyota executive living in Tokyo, who claimed to be unaware of the law, was arrested for importing oxycodone into Japan.[158][159]

Singaporeedit

Oxycodone is listed as a Class A drug in the Misuse of Drugs Act of Singapore, which means offences concerning the drug attract the most severe level of punishment. A conviction for unauthorized manufacture of the drug attracts a minimum sentence of 10 years of imprisonment and corporal punishment of 5 strokes of the cane, and a maximum sentence of life imprisonment or 30 years of imprisonment and 15 strokes of the cane.[160] The minimum and maximum penalties for unauthorized trafficking in the drug are respectively 5 years of imprisonment and 5 strokes of the cane, and 20 years of imprisonment and 15 strokes of the cane.[161]

United Kingdomedit

Oxycodone is a Class A drug under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971.[162] For Class A drugs, which are "considered to be the most likely to cause harm", possession without a prescription is punishable by up to seven years in prison, an unlimited fine, or both.[163] Dealing of the drug illegally is punishable by up to life imprisonment, an unlimited fine, or both.[163] Oxycodone is a Schedule 2 drug per the Misuse of Drugs Regulations 2001 which "provide certain exemptions from the provisions of the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971".[164]

United Statesedit

Under the Controlled Substances Act, oxycodone is a Schedule II controlled substance whether by itself or part of a multi-ingredient medication.[165] The DEA lists oxycodone both for sale and for use in manufacturing other opioids as ACSCN 9143 and in 2013 approved the following annual aggregate manufacturing quotas: 131.5 metric tons for sale, down from 153.75 in 2012, and 10.25 metric tons for conversion, unchanged from the previous year.[166] In 2020, oxycodone possession was decriminalized in the U.S. state of Oregon.[167]

Economicsedit

The International Narcotics Control Board estimated 11.5 short tons (10.4 t) of oxycodone were manufactured worldwide in 1998;[168] by 2007 this figure had grown to 75.2 short tons (68.2 t).[168] United States accounted for 82% of consumption in 2007 at 51.6 short tons (46.8 t). Canada, Germany, Australia, and France combined accounted for 13% of consumption in 2007.[168][169] In 2010, 1.3 short tons (1.2 t) of oxycodone were illegally manufactured using a fake pill imprint. This accounted for 0.8% of consumption. These illicit tablets were later seized by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, according to the International Narcotics Control Board.[170] The board also reported 122.5 short tons (111.1 t) manufactured in 2010. This number had decreased from a record high of 135.9 short tons (123.3 t) in 2009.[171]

Namesedit

Expanded expressions for the compound oxycodone in the academic literature include "dihydrohydroxycodeinone",[1][172][173] "Eucodal",[172][173] "Eukodal",[5][13] "14-hydroxydihydrocodeinone",[1][172] and "Nucodan".[172][173] In a UNESCO convention, the translations of "oxycodone" are oxycodon (Dutch), oxycodone (French), oxicodona (Spanish), الأوكسيكودون (Arabic), 羟考酮 (Chinese), and оксикодон (Russian).[174]

The word "oxycodone" should not be confused with "oxandrolone", "oxazepam", "oxybutynin", "oxytocin", or "Roxanol".[175]

Other brand names include Longtec and Shortec.[176]

Referencesedit

- ^ a b c O'Neil MJ, ed. (2006). The Merck index (14th ed.). Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck & Co. ISBN 978-0-911910-00-1.

- ^ "Oxycodone Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. 14 October 2019. Archived from the original on 19 June 2020. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ^ Bonewit-West K, Hunt SA, Applegate E (2012). Today's Medical Assistant: Clinical and Administrative Procedures. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 571. ISBN 978-1-4557-0150-6. Archived from the original on 6 October 2022. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- ^ Bonewit-West K, Hunt SA, Applegate E (2012). Today's Medical Assistant: Clinical and Administrative Procedures. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 571. ISBN 9781455701506. Archived from the original on 10 January 2023. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- ^ a b c d Kalso E (May 2005). "Oxycodone". Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 29 (5 Suppl): S47–S56. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.01.010. PMID 15907646.

- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ a b c d "Roxicodone, OxyContin (oxycodone) dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Archived from the original on 13 April 2014. Retrieved 8 April 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f Elliott JA, Smith HS (19 April 2016). Handbook of Acute Pain Management. CRC Press. pp. 82–. ISBN 978-1-4665-9635-1.

- ^ a b c "Roxicodone, OxyContin (oxycodone) dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Archived from the original on 13 April 2014. Retrieved 4 January 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Smith H, Passik S (25 April 2008). Pain and Chemical Dependency. Oxford University Press USA. pp. 195–. ISBN 978-0-19-530055-0. Archived from the original on 7 October 2022. Retrieved 5 October 2016.

- ^ Yarbro CH, Wujcik D, Gobel BH (15 November 2010). Cancer Nursing: Principles and Practice. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. pp. 695–. ISBN 978-1-4496-1829-2.

- ^ a b c d McPherson RA, Pincus MR (31 March 2016). Henry's Clinical Diagnosis and Management by Laboratory Methods. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 336–. ISBN 978-0-323-41315-2.

- ^ a b c d e f Sunshine A, Olson NZ, Colon A, Rivera J, Kaiko RF, Fitzmartin RD, et al. (July 1996). "Analgesic efficacy of controlled-release oxycodone in postoperative pain". Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 36 (7): 595–603. doi:10.1002/j.1552-4604.1996.tb04223.x. PMID 8844441. S2CID 35076787.

Treatment with CR oxycodone was safe and effective in this study, and its characteristics will be beneficial in the treatment of pain.

- ^ Remillard D, Kaye AD, McAnally H (February 2019). "Oxycodone's Unparalleled Addictive Potential: Is it Time for a Moratorium?". Current Pain and Headache Reports. 23 (2): 15. doi:10.1007/s11916-019-0751-7. PMID 30820686. S2CID 73488265.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Oxycodone Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. AHFS. Archived from the original on 28 December 2018. Retrieved 28 December 2018.

- ^ a b Pergolizzi JV, Taylor R, LeQuang JA, Raffa RB (2018). "Managing severe pain and abuse potential: the potential impact of a new abuse-deterrent formulation oxycodone/naltrexone extended-release product". Journal of Pain Research. 11: 301–311. doi:10.2147/JPR.S127602. PMC 5810535. PMID 29445297.

- ^ British national formulary : BNF 74 (74 ed.). British Medical Association. 2017. p. 442. ISBN 978-0-85711-298-9.

- ^ a b Talley NJ, Frankum B, Currow D (10 February 2015). Essentials of Internal Medicine 3e. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 491–. ISBN 978-0-7295-8081-6.

- ^ "Opioid Conversion / Equivalency Table". Stanford School of Medicine, Palliative Care. 20 April 2013. Archived from the original on 9 September 2020. Retrieved 27 October 2017.

- ^ Kalso E (May 2005). "Oxycodone". Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 29 (5 Suppl): S47–S56. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.01.010. PMID 15907646.

- ^ World Health Organization (2021). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 22nd list (2021). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/345533. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2021.02.

- ^ "The Top 300 of 2021". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 15 January 2024. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ "Oxycodone – Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ Dart RC, Iwanicki JL, Dasgupta N, Cicero TJ, Schnoll SH (2017). "Do abuse deterrent opioid formulations work?". Journal of Opioid Management. 13 (6): 365–378. doi:10.5055/jom.2017.0415. PMID 29308584.

- ^ Riley J, Eisenberg E, Müller-Schwefe G, Drewes AM, Arendt-Nielsen L (January 2008). "Oxycodone: a review of its use in the management of pain". Current Medical Research and Opinion. 24 (1): 175–192. doi:10.1185/030079908X253708. PMID 18039433. S2CID 9099037.

- ^ Ueberall MA, Eberhardt A, Mueller-Schwefe GH (24 February 2016). "Quality of life under oxycodone/naloxone, oxycodone, or morphine treatment for chronic low back pain in routine clinical practice". International Journal of General Medicine. 9: 39–51. doi:10.2147/IJGM.S94685. PMC 4771398. PMID 26966387.

- ^ Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R (March 2016). "CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain - United States, 2016". MMWR. Recommendations and Reports. 65 (1): 1–49. doi:10.15585/mmwr.rr6501e1er. PMC 6390846. PMID 26987082.

- ^ Roth AR, Lazris A, Haskell H, James J (September 2020). "Appropriate Use of Opioids for Chronic Pain". American Family Physician. 102 (6): 335–337. PMID 32931211.

- ^ a b Biancofiore G (September 2006). "Oxycodone controlled release in cancer pain management". Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management. 2 (3): 229–234. doi:10.2147/tcrm.2006.2.3.229. PMC 1936259. PMID 18360598.

- ^ Hanks GW, Conno F, Cherny N, Hanna M, Kalso E, McQuay HJ, et al. (March 2001). "Morphine and alternative opioids in cancer pain: the EAPC recommendations". British Journal of Cancer. 84 (5): 587–593. doi:10.1054/bjoc.2001.1680. PMC 2363790. PMID 11237376.

- ^ "FDA approves OxyContin for kids 11 to 16". www.msn.com. Archived from the original on 30 June 2017. Retrieved 11 February 2018.

- ^ "Restless Legs Syndrome | Baylor Medicine". www.bcm.edu. Retrieved 6 November 2023.

- ^ Gould III HJ (11 December 2006). Understanding Pain: What It Is, Why It Happens, and How It's Managed. Demos Medical Publishing. pp. 71–. ISBN 978-1-934559-82-6.

- ^ Graves K (29 September 2015). Drug I.D. & Symptom Guide. QWIK-CODE (6th ed.). LawTech Publishing Group. pp. 99–. ISBN 978-1-56325-225-9.

- ^ Skidmore-Roth L (16 July 2015). Mosby's Drug Guide for Nursing Students, with 2016 Update. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 789–. ISBN 978-0-323-17297-4. Archived from the original on 7 October 2022. Retrieved 5 October 2016.

- ^ "accessdata.fda.gov" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 February 2017. Retrieved 11 February 2018.

- ^ Sinatra RS, de Leon-Cassasola OA (27 April 2009). Acute Pain Management. Cambridge University Press. pp. 198–. ISBN 978-0-521-87491-5. Archived from the original on 7 October 2022. Retrieved 5 October 2016.

- ^ Staats PS, Silverman SM (28 May 2016). Controlled Substance Management in Chronic Pain: A Balanced Approach. Springer. pp. 172–. ISBN 978-3-319-30964-4. Archived from the original on 7 October 2022. Retrieved 5 October 2016.

- ^ "FDA Approves Troxyca® ER (Oxycodone Hydrochloride and Naltrexone Hydrochloride) Extended-release Capsules CII with Abuse-deterrent Properties for the Management of Pain". 19 August 2016. Archived from the original on 25 September 2020. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f Davis MP (28 May 2009). Opioids in Cancer Pain. OUP Oxford. pp. 155–158. ISBN 978-0-19-923664-0. Archived from the original on 7 October 2022. Retrieved 5 October 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Forbes K (29 November 2007). Opioids in Cancer Pain. OUP Oxford. pp. 64–65. ISBN 978-0-19-921880-6.

- ^ Bradbury H, Hodge BS (8 November 2013). Practical Prescribing for Medical Students. SAGE Publications. pp. 93–. ISBN 978-1-4462-9753-7. Archived from the original on 7 October 2022. Retrieved 5 October 2016.

- ^ American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (23 March 2009). "Oxycodone". U.S. National Library of Medicine, MedlinePlus. Archived from the original on 24 March 2009. Retrieved 27 March 2009.

- ^ a b c d Fitzgibbon DR, Loeser JD (28 March 2012). Cancer Pain. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 198–. ISBN 978-1-4511-5279-1.

- ^ "Oxycodone Side Effects". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 21 June 2013. Retrieved 22 May 2013.

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Oxycodone

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk