A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

Javanese

| |

|---|---|

| Script type | |

Time period | c. 15th–present |

| Direction | Left-to-right |

| Languages | Javanese, Sundanese, Madurese, Sasak, Indonesian, Kawi, Sanskrit |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | |

Sister systems | Balinese alphabet Batak alphabet Baybayin scripts Lontara alphabet Makasar Sundanese script Rencong alphabet Rejang alphabet |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Java (361), Javanese |

| Unicode | |

Unicode alias | Javanese |

| U+A980–U+A9DF | |

| Brahmic scripts |

|---|

| The Brahmi script and its descendants |

The Javanese script (natively known as Aksara Jawa, Hanacaraka, Carakan, and Dentawyanjana)[1] is one of Indonesia's traditional scripts developed on the island of Java. The script is primarily used to write the Javanese language, but in the course of its development has also been used to write several other regional languages such as Sundanese, Madurese, and Sasak; the lingua franca of the region, Malay; as well as the historical languages Kawi and Sanskrit. Javanese script was actively used by the Javanese people for writing day-to-day and literary texts from at least the mid-15th century CE until the mid-20th century CE, before its function was gradually supplanted by the Latin alphabet. Today the script is taught in DI Yogyakarta, Central Java, and the East Java Province as part of the local curriculum, but with very limited function in everyday use.[2][3]

The Javanese script is an abugida writing system which consists of 20 to 33 basic letters, depending on the language being written. Like other Brahmic scripts, each letter (called an aksara) represents a syllable with the inherent vowel /a/ or /ɔ/ which can be changed with the placement of diacritics around the letter. Each letter has a conjunct form called pasangan, which nullifies the inherent vowel of the previous letter. Traditionally, the script is written without space between words (scriptio continua) but is interspersed with a group of decorative punctuation.

History

The Javanese script's evolutionary history can be traced fairly well due to the significant amount of inscriptional evidences left behind throughout allowed for epigraphical studies to be carried out. The oldest root of the Javanese script is the Tamil-Brahmi script which evolved into the Pallava script in Southern and Southeast Asia between the 6th and 8th centuries. Pallava script, in turn, evolved into the Kawi script which was actively used throughout Indonesia's Hindu-Buddhist period between the 8th and 15th centuries. In various parts of Indonesia, Kawi script would then evolve into Indonesia's various traditional scripts, one of them being Javanese script.[4] The modern Javanese script seen today evolved from Kawi script between the 14th and 15th centuries, a period in which Java began to receive significant Islamic influence.[5][6][7]

For around 500 years, from the 15th until the mid-20th century, Javanese script was actively used by the Javanese people for writing day-to-day and literary texts with a wide range of themes and content. Javanese script was used throughout the island at a time when there was no easy means of communication between remote areas and no impulse towards standardization. As a result, there is a huge variety in historical and local styles of Javanese writing throughout the ages. The ability of a person to read a bark-paper manuscript from the town of Demak written around 1700 is no guarantee that the same person would also be able to make sense of a palm-leaf manuscript written at the same time only 50 miles away on the slopes of Mount Merapi. The great differences between regional styles almost makes it seem that the "Javanese script" is in fact a family of scripts.[8] Javanese writing traditions were especially cultivated in the Kraton environment in Javanese cultural centers, such as Yogyakarta and Surakarta. However, Javanese texts are known to be made and used by various layers of society with varying usage intensities between regions. In West Java, for example, Javanese script was mainly used by the Sundanese nobility (ménak) due to the political influence of the Mataram kingdom.[9] However, most Sundanese people within the same time period more commonly used the Pegon script which was adapted from the Arabic alphabet.[10] Javanese literature is almost always composed in metrical verses that are designed to be sung, thus Javanese texts are not only judged by their content and language but also by the merit of their melody and rhythm during recitation sessions.[11] Javanese writing tradition also relied on periodic copying due to deterioration of writing materials in the tropical Javanese climate; as a result, many physical manuscripts that are available now are 18th or 19th century copies, though their contents can usually be traced to far older prototypes.[7]

Media

Javanese script has been written with numerous media that have shifted over time. Kawi script, which is ancestral to Javanese script, is often found on stone inscriptions and copper plates. Everyday writing in Kawi was done in palm leaf form locally known as lontar, which are processed leaves of the tal palm (Borassus flabellifer). Each lontar leaf has the shape of a slim rectangle 2.8 to 4 cm in width and varied length between 20 and 80 cm. Each leaf can only accommodate around 4 lines of writing, which are incised in horizontal orientation with a small knife and then blackened with soot to increase readability. This media has a long history of attested use all over South and Southeast Asia.[12]

In the 13th century, paper began to be used in the Malay archipelago. This introduction is related to spread of Islam in the region, due to the Islamic writing tradition that is supported by the use of paper and codex manuscript. As Java began to receive significant Islamic influence in the 15th century, coinciding with the period in which the Kawi script began to transition into the modern Javanese script, paper became widespread in Java while the use of lontar only persisted in a few places.[13] There are two kinds of paper that are commonly used in Javanese manuscript: locally produced paper called daluang, and imported paper. Daluang (also spelled dluwang) is a paper made from the beaten bark of the saéh tree (Broussonetia papyrifera). Visually, daluang can be easily differentiated from regular paper by its distinctive brown tint and fibrous appearance. A well made daluang has a smooth surface and is quite durable against manuscript damage commonly associated with tropical climates, especially insect damage. Meanwhile, a coarse daluang has a bumpy surface and tends to break easily. Daluang is commonly used in manuscripts produced by Javanese Kratons (palaces) and pesantren (Islamic boarding schools) between the 16th to 17th centuries.[14]

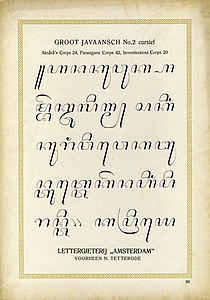

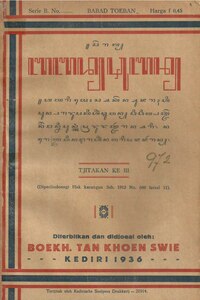

Most imported paper in Indonesian manuscripts came from Europe. In the beginning, only a few scribes were able to use European paper due to its high cost—paper made with using European methods of the time could only be imported in limited number.[a] In colonial administration, the use of European paper had to be supplemented with Javanese daluang and imported Chinese paper until at least the 19th century. As paper supply increased due to growing imports from Europe, scribes in palaces and urban settlements gradually opted to use European paper as the primary media for writing, while daluang paper was increasingly associated with pesantren and rural manuscripts.[13] Alongside the increase of European paper supply, attempts to create Javanese printing type began, spearheaded by several European figures. With the establishment of printing technology in 1825, materials in Javanese script could be mass-produced and became increasingly common in various aspect of pre-independence Javanese life, from letters, books, and newspapers, to magazines, and even advertisements and paper currency.[15]

Usage

| Usage of the Javanese Script | |

|

For at least 500 years, from the 15th century until the mid 20th century, Javanese script was used by all layers of Javanese society for writing day-to-day and literary texts with a wide range of theme and content. Due to the significant influence of oral tradition, reading in pre-independence Javanese society is usually a performance; Javanese literature texts are almost always composed in metrical verses that are designed to be recited, thus Javanese texts are not only judged by their content and language, but also by the merit of their melody and rhythm during recitation sessions.[11] Javanese poets are not expected to create new stories and characters; instead the role of the poet is to rewrite and recompose existing stories into forms that are suitable to local taste and prevailing trends. As a result, Javanese literary works such as the Cerita Panji do not have a single authoritative version referenced by all others, instead, the Cerita Panji is a loose collection of numerous tales with various versions bound together by the common thread of the Panji character.[16] Literature genres with the longest attested history are Sanskrit epics such as the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, which have been recomposed since the Kawi period and which introduced hundreds of characters familiar in Javanese wayang stories today, including Arjuna, Srikandi, Ghatotkacha and many others. Since the introduction of Islam, characters of Middle-Eastern provenance such as Amir Hamzah and the Prophet Joseph have also been frequent subjects of writing. There are also local characters, usually set in Java's semi-legendary past, such as Prince Panji, Damar Wulan, and Calon Arang.[17]

When studies of Javanese language and literature began to attract European attention in the 19th century, an initiative to create a Javanese movable type began to take place in order to mass-produce and quickly disseminate Javanese literary materials. One of the earliest attempts to create a movable Javanese type was by Paul van Vlissingen. His typeface was first put in use in the Bataviasche Courant newspaper's October 1825 issue.[18] While lauded as a considerable technical achievement, many at the time felt that Vlissingen's design was a coarse copy of the fine Javanese hand used in literary texts, and so this early attempt was further developed by numerous other people to varying degrees of success as the study of Javanese developed over the years.[19] In 1838, Taco Roorda completed his typeface, known as Tuladha Jejeg, that was based on the hand of Surakartan scribes[b] with some European typographical elements mixed in. Roorda's font garnered positive feedback and soon became the main choice to print any Javanese text. From then, reading materials in printed Javanese using Roorda's typeface became widespread among the Javanese populace and were widely used in materials other than literature. The establishment of print technology enabled a printing industry which, for the next century, produced various materials in printed Javanese, from administrative papers and school books, to mass media such as the Kajawèn magazine which was entirely printed in Javanese in all of its article and columns.[15][21] In the governmental context, one application of the Javanese script was the multilingual legal text on the Netherlands Indies gulden banknotes circulated by the Bank of Java.[22]

Decline

As literacy and demand for reading materials increased in the beginning of the 20th century, Javanese publishers paradoxically began to decrease the amount of Javanese script publication due to a practical and economic consideration: printing any text in Javanese script at the time required twice the amount of paper compared to the same text rendered in the Latin alphabet, so that Javanese texts were more expensive and time-consuming to produce. In order to lower production costs and keep book prices affordable to the general populace, many publishers (such as the government-owned Balai Pustaka) gradually prioritized publication in the Latin alphabet.[23][c] However, the Javanese population at the beginning of the 20th century maintained the use of Javanese script in various aspects of everyday life. It was, for example, considered more polite to write a letter using Javanese script, especially one addressed toward an elder or superior. Many publishers, including Balai Pustaka, continued to print books, newspapers, and magazines in Javanese script due to sufficient, albeit declining, demand. The use of Javanese script only started to drop significantly during the Japanese occupation of the Dutch East Indies beginning in 1942.[25] Some writers attribute this sudden decline to prohibitions issued by the Japanese government banning the use of native script in the public sphere, though no documentary evidence of such a ban has yet been found.[d] Nevertheless, the use of Javanese script did decline significantly during the Japanese occupation and it never recovered its previous widespread use in post-independence Indonesia.

Contemporary use

In contemporary usage, Javanese script is still taught as part of the local curriculum in Yogyakarta, Central Java, and the East Java Province. Several local newspapers and magazines have columns written in Javanese script, and the script can frequently be seen on public signage. However, many contemporary attempts to revive Javanese script are symbolic rather than functional; there are no longer, for example, periodicals like Kajawèn magazine that publish significant content in Javanese script. Most Javanese people today know the existence of the script and recognize a few letters, but it is rare to find someone who can read and write it meaningfully.[27][28] Therefore, as recently as 2019, it is not uncommon to see Javanese script signage in public places with numerous misspellings and basic mistakes.[29][30] Several hurdles in revitalizing the use of Javanese script includes information technology equipment that does not support correct rendering of the Javanese script, lack of governing bodies with sufficient competence to consult on its usage, and lack of typographical explorations that may intrigue contemporary viewers. Nevertheless, attempts to revive the script are still being conducted by several communities and public figures who encouraged the use of Javanese script in the public sphere, especially with digital devices.[31]

Form

Letter

A basic letter in the Javanese script is called an aksara which represents a syllable. Javanese script contains around 45 letters, but not all of them are used equally. Over the course of its development, some letters became obsolete and some are only used in certain contexts. As such, it is common to divide the letters in several groups based on their function.

Wyanjana

The Aksara wyanjana (ꦲꦏ꧀ꦱꦫ ꦮꦾꦚ꧀ꦗꦤ) are consonant letters with an inherent vowel, either /a/ or /ɔ/. As a Brahmi derived script, the Javanese script originally had 33 wyanjana letters to write the 33 consonants that are used in Sanskrit and Kawi. Their forms are as follows:[32][33]

| Place of articulation | Pancawalimukha | Semivowel | Sibilant | Fricative | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unvoiced | Voiced | Nasal | ||||||||

| Unaspirated | Aspirated | Unaspirated | Aspirated | |||||||

| Velar | ꦏ ka |

ꦑ kha |

ꦒ ga |

ꦓ gha |

ꦔ ṅa |

ꦲ ha/a1 | ||||

| Palatal | ꦕ ca |

ꦖ cha |

ꦗ ja |

ꦙ jha |

ꦚ ña |

ꦪ ya |

ꦯ śa |

|||

| Retroflex | ꦛ ṭa |

ꦜ ṭha |

ꦝ ḍa |

ꦞ ḍha |

ꦟ ṇa |

ꦫ ra |

ꦰ ṣa |

|||

| Dental | ꦠ ta |

ꦡ tha |

ꦢ da |

ꦣ dha |

ꦤ na |

ꦭ la |

ꦱ sa |

|||

| Labial | ꦥ pa |

ꦦ pha |

ꦧ ba |

ꦨ bha |

ꦩ ma |

ꦮ wa |

||||

Notes

| ||||||||||

Over the course of its development, the modern Javanese language no longer uses all letters in the Sanskrit-Kawi inventory. The modern Javanese script only uses 20 consonants and 20 basic letters known as aksara nglegéna (ꦲꦏ꧀ꦱꦫ ꦔ꧀ꦭꦼꦒꦺꦤ). Some of the remaining letters are repurposed as aksara murda (ꦲꦏ꧀ꦱꦫ ꦩꦸꦂꦢ) which are used for honorific purposes in writing respected names, be it legendary (for example Bima ꦨꦶꦩ) or real (for example Pakubuwana ꦦꦑꦸꦨꦸꦮꦟ).[34] From the 20 nglegéna basic letters, only 9 have corresponding murda forms. Because of this, the use of murda is not identical to capitalization of proper names in Latin orthography;[34] if the first syllable of a name does not have a murda form, the second syllable would use murda. If the second syllable also does not have a murda form, the third syllable would use murda, and so on. Highly respected names may be written completely in murda if possible, but in essence, the use of murda is optional and may be inconsistent in traditional texts. For example, the name Gani can be spelled as ꦒꦤꦶ (without murda), ꦓꦤꦶ (with murda on the first syllable), or ꦓꦟꦶ (with murda on all syllables) depending on the background and context of the writing. The remaining letters that are not classified as nglegéna or repurposed as murda are aksara mahaprana, letters that are used in Sanskrit and Kawi texts but obsolete in modern Javanese.[32][e]

| ha/a1 | na | ca | ra | ka | da | ta | sa | wa | la | pa | dha | ja | ya | nya | ma | ga | ba | tha | nga | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nglegena | ꦲ |

ꦤ |

ꦕ |

ꦫ |

ꦏ |

ꦢ |

ꦠ |

ꦱ |

ꦮ |

ꦭ |

ꦥ |

ꦝ |

ꦗ |

ꦪ |

ꦚ |

ꦩ |

ꦒ |

ꦧ |

ꦛ |

ꦔ | ||

| Murda | ꦟ |

ꦖ2 |

ꦬ3 |

ꦑ |

ꦡ |

ꦯ |

ꦦ |

ꦘ |

ꦓ |

ꦨ |

||||||||||||

| Mahaprana | ꦣ |

ꦰ |

ꦞ |

ꦙ |

ꦜ |

|||||||||||||||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||||||||

Swara

Aksara swara (ꦲꦏ꧀ꦱꦫ ꦱ꧀ꦮꦫ) are letters that represent pure vowels. Javanese script has 14 vowel letters inherited from the Sanskrit tradition. Their forms are as follows:[33]