A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Indonesian | |

|---|---|

| Bahasa Indonesia | |

| Pronunciation | [baˈha.sa in.doˈne.si.ja] |

| Native to | Indonesia |

| Region | Indonesia (as official language) Significant language speakers: East Timor, Malaysia, Singapore, Saudi Arabia, Australia, Taiwan, Netherlands, others |

| Ethnicity | Over 1,300 Indonesian ethnic groups |

Native speakers | L1 speakers: 43 million (2010 census)[1] L2 speakers: 156 million (2010 census)[1] Total speakers: 300 million (2022)[2] |

Early forms | |

Standard forms | |

| Dialects |

|

| Latin (Indonesian alphabet) Indonesian Braille | |

| SIBI (Manually Coded Indonesian) | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Regulated by | Language Development and Fostering Agency (Badan Pengembangan dan Pembinaan Bahasa) |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | id |

| ISO 639-2 | ind |

| ISO 639-3 | ind |

| Glottolog | indo1316 |

| Linguasphere | 33-AFA-ac |

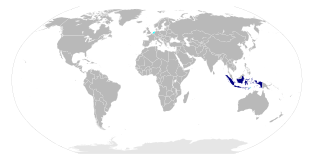

Countries of the world where Indonesian is a majority native language

Countries where Indonesian is a minority language | |

Indonesian (Bahasa Indonesia; [baˈhasa indoˈnesija]) is the official and national language of Indonesia.[8] It is a standardized variety of Malay,[9] an Austronesian language that has been used as a lingua franca in the multilingual Indonesian archipelago for centuries. Indonesia is the fourth most populous nation in the world, with over 279 million inhabitants of which the majority speak Indonesian, which makes it one of the most widely spoken languages in the world.[10] Indonesian vocabulary has been influenced by various regional languages (such as Javanese, Sundanese, Minangkabau, Balinese, Banjarese, Buginese, etc.) and foreign languages (such as Arabic, Dutch, Portuguese, and English). Many borrowed words have been adapted to fit the phonetic and grammatical rules of Indonesian.

Most Indonesians, aside from speaking the national language, are fluent in at least one of the more than 700 indigenous local languages; examples include Javanese and Sundanese, which are commonly used at home and within the local community.[11][12] However, most formal education and nearly all national mass media, governance, administration, and judiciary and other forms of communication are conducted in Indonesian.[13]

Under Indonesian rule from 1976 to 1999, Indonesian was designated as the official language of Timor Leste. It has the status of a working language under the country's constitution along with English.[7][14]: 3 [15] In November 2023, the Indonesian language was recognized as one of the official languages of the UNESCO General Conference.

The term Indonesian is primarily associated with the national standard dialect (bahasa baku).[16] However, in a looser sense, it also encompasses the various local varieties spoken throughout the Indonesian archipelago.[9][17] Standard Indonesian is confined mostly to formal situations, existing in a diglossic relationship with vernacular Malay varieties, which are commonly used for daily communication, coexisting with the aforementioned regional languages and with Malay creoles;[16][11] standard Indonesian is spoken in informal speech as a lingua franca between vernacular Malay dialects, Malay creoles, and regional languages.

The Indonesian name for the language (bahasa Indonesia) is also occasionally used in English and other languages. Bahasa Indonesia is sometimes improperly reduced to Bahasa, which refers to the Indonesian subject (Bahasa Indonesia) taught in schools, on the assumption that this is the name of the language. But the word bahasa only means language. For example, French language is translated as bahasa Prancis, and the same applies to other languages, such as bahasa Inggris (English), bahasa Jepang (Japanese), bahasa Arab (Arabic), bahasa Italia (Italian), and so on. Indonesians generally may not recognize the name Bahasa alone when it refers to their national language.[18]

History

Early kingdoms era

Standard Indonesian is a standard language of "Riau Malay",[4][5] which despite its common name is not based on the vernacular Malay dialects of the Riau Islands, but rather represents a form of Classical Malay as used in the 19th and early 20th centuries in the Riau-Lingga Sultanate. Classical Malay had emerged as a literary language in the royal courts along both shores of the Strait of Malacca, including the Johor Sultanate and Malacca Sultanate.[19][20][21] Originally spoken in Northeast Sumatra,[22] Malay has been used as a lingua franca in the Indonesian archipelago for half a millennium. It might be attributed to its ancestor, the Old Malay language (which can be traced back to the 7th century). The Kedukan Bukit Inscription is the oldest surviving specimen of Old Malay, the language used by Srivijayan empire.[23] Since the 7th century, the Old Malay language has been used in Nusantara (archipelago) (Indonesian archipelago), evidenced by Srivijaya inscriptions and by other inscriptions from coastal areas of the archipelago, such as Sojomerto inscription.[23]

Old Malay as lingua franca

Trade contacts carried on by various ethnic peoples at the time were the main vehicle for spreading the Old Malay language, which was the main communications medium among the traders. Ultimately, the Old Malay language became a lingua franca and was spoken widely by most people in the archipelago.[25][26]

Indonesian (in its standard form) has essentially the same material basis as the Malaysian standard of Malay and is therefore considered to be a variety of the pluricentric Malay language. However, it does differ from Malaysian Malay in several respects, with differences in pronunciation and vocabulary. These differences are due mainly to the Dutch and Javanese influences on Indonesian. Indonesian was also influenced by the Melayu pasar (lit. 'market Malay'), which was the lingua franca of the archipelago in colonial times, and thus indirectly by other spoken languages of the islands.

Malaysian Malay claims to be closer to the classical Malay of earlier centuries, even though modern Malaysian has been heavily influenced, in lexicon as well as in syntax, by English. The question of whether High Malay (Court Malay) or Low Malay (Bazaar Malay) was the true parent of the Indonesian language is still in debate. High Malay was the official language used in the court of the Johor Sultanate and continued by the Dutch-administered territory of Riau-Lingga, while Low Malay was commonly used in marketplaces and ports of the archipelago. Some linguists have argued that it was the more common Low Malay that formed the base of the Indonesian language.[27]

Colonial era and the birth of Indonesian

When the Dutch East India Company (VOC) first arrived in the archipelago at the start of the 1600s, the Malay language was a significant trading and political language due to the influence of the Malaccan Sultanate and later the Portuguese. However, the language had never been dominant among the population of the Indonesian archipelago as it was limited to mercantile activity. The VOC adopted the Malay language as the administrative language of their trading outpost in the east. Following the bankruptcy of the VOC, the Batavian Republic took control of the colony in 1799, and it was only then that education in and promotion of Dutch began in the colony. Even then, Dutch administrators were remarkably reluctant to promote the use of Dutch compared to other colonial regimes. Dutch thus remained the language of a small elite: in 1940, only 2% of the total population could speak Dutch. Nevertheless, it did have a significant influence on the development of Malay in the colony: during the colonial era, the language that would be standardized as Indonesian absorbed a large amount of Dutch vocabulary in the form of loanwords.

The nationalist movement that ultimately brought Indonesian to its national language status rejected Dutch from the outset. However, the rapid disappearance of Dutch was a very unusual case compared with other colonized countries, where the colonial language generally has continued to function as the language of politics, bureaucracy, education, technology, and other fields of importance for a significant time after independence.[28] The Indonesian scholar Soenjono Dardjowidjojo even goes so far as to say that when compared to the situation in other Asian countries such as India, Malaysia, Singapore and the Philippines, "Indonesian is perhaps the only language that has achieved the status of a national language in its true sense" since it truly dominates in all spheres of Indonesian society.[29] The ease with which Indonesia eliminated the language of its former colonial power can perhaps be explained as much by Dutch policy as by Indonesian nationalism. In marked contrast to the French, Spanish and Portuguese, who pursued an assimilation colonial policy, or even the British, the Dutch did not attempt to spread their language among the indigenous population. In fact, they consciously prevented the language from being spread by refusing to provide education, especially in Dutch, to the native Indonesians so they would not come to see themselves as equals.[28] Moreover, the Dutch wished to prevent the Indonesians from elevating their perceived social status by taking on elements of Dutch culture. Thus, until the 1930s, they maintained a minimalist regime and allowed Malay to spread quickly throughout the archipelago.

Dutch dominance at that time covered nearly all aspects, with official forums requiring the use of Dutch, although since the Second Youth Congress (1928) the use of Indonesian as the national language was agreed on as one of the tools in the independence struggle. As of it, Mohammad Hoesni Thamrin inveighed actions underestimating Indonesian. After some criticism and protests, the use of Indonesian was allowed since the Volksraad sessions held in July 1938.[30] By the time they tried to counter the spread of Malay by teaching Dutch to the natives, it was too late, and in 1942, the Japanese conquered Indonesia. The Japanese mandated that all official business be conducted in Indonesian and quickly outlawed the use of the Dutch language.[31] Three years later, the Indonesians themselves formally abolished the language and established bahasa Indonesia as the national language of the new nation.[32] The term bahasa Indonesia itself had been proposed by Mohammad Tabrani in 1926,[33] and Tabrani had further proposed the term over calling the language Malay language during the First Youth Congress in 1926.[3]

Indonesian language (old VOS spelling):

Jang dinamakan 'Bahasa Indonesia' jaitoe bahasa Melajoe jang soenggoehpoen pokoknja berasal dari 'Melajoe Riaoe' akan tetapi jang soedah ditambah, dioebah ataoe dikoerangi menoeroet keperloean zaman dan alam baharoe, hingga bahasa itoe laloe moedah dipakai oleh rakjat diseloeroeh Indonesia; pembaharoean bahasa Melajoe hingga menjadi bahasa Indonesia itoe haroes dilakoekan oleh kaoem ahli jang beralam baharoe, ialah alam kebangsaan Indonesia

Indonesian (modern EYD spelling):

Yang dinamakan 'Bahasa Indonesia' yaitu bahasa Melayu yang sungguhpun pokoknya berasal dari 'Melayu Riau' akan tetapi yang sudah ditambah, diubah atau dikurangi menurut keperluan zaman dan alam baru, hingga bahasa itu lalu mudah dipakai oleh rakyat di seluruh Indonesia; pembaharuan bahasa Melayu hingga menjadi bahasa Indonesia itu harus dilakukan oleh kaum ahli yang beralam baru, ialah alam kebangsaan Indonesia

English:

"What is named as 'Indonesian language' is a true Malay language derived from 'Riau Malay' but which had been added, modified or subscribed according to the requirements of the new age and nature, until it was then used easily by people across Indonesia; the renewal of Malay language until it became Indonesian it had to be done by the experts of the new nature, the national nature of Indonesia"

— Ki Hajar Dewantara in the Congress of Indonesian Language I 1938, Solo[34][35]

Several years prior to the congress, Swiss linguist, Renward Brandstetter wrote An Introduction to Indonesian Linguistics in 4 essays from 1910 to 1915. The essays were translated into English in 1916. By "Indonesia", he meant the name of the geographical region, and by "Indonesian languages" he meant Malayo-Polynesian languages west of New Guinea, because by that time there was still no notion of Indonesian language.

Sutan Takdir Alisjahbana was a great promoter of the use and development of Indonesian and he was greatly exaggerating the decline of Dutch. Higher education was still in Dutch and many educated Indonesians were writing and speaking in Dutch in many situations (and were still doing so well after independence was achieved). He believed passionately in the need to develop Indonesian so that it could take its place as a fully adequate national language, able to replace Dutch as a means of entry into modern international culture. In 1933, he began the magazine Pujangga Baru (New Writer — Poedjangga Baroe in the original spelling) with co-editors Amir Hamzah and Armijn Pane. The language of Pujangga Baru came in for criticism from those associated with the more classical School Malay and it was accused of publishing Dutch written with an Indonesian vocabulary. Alisjahbana would no doubt have taken the criticism as a demonstration of his success. To him the language of Pujangga Baru pointed the way to the future, to an elaborated, Westernised language able to express all the concepts of the modern world. As an example, among the many innovations they condemned was use of the word bisa instead of dapat for 'can'. In Malay bisa meant only 'poison from an animal's bite' and the increasing use of Javanese bisa in the new meaning they regarded as one of the many threats to the language's purity. Unlike more traditional intellectuals, he did not look to Classical Malay and the past. For him, Indonesian was a new concept; a new beginning was needed and he looked to Western civilisation, with its dynamic society of individuals freed from traditional fetters, as his inspiration.[10]

The prohibition on use of Dutch led to an expansion of Indonesian language newspapers and pressure on them to increase the language's wordstock. The Japanese agreed to the establishment of the Komisi Bahasa (Language Commission) in October 1942, formally headed by three Japanese but with a number of prominent Indonesian intellectuals playing the major part in its activities. Soewandi, later to be Minister of Education and Culture, was appointed secretary, Alisjahbana was appointed an 'expert secretary' and other members included the future president and vice-president, Sukarno and Hatta. Journalists, beginning a practice that has continued to the present, did not wait for the Komisi Bahasa to provide new words, but actively participated themselves in coining terms. Many of the Komisi Bahasa's terms never found public acceptance and after the Japanese period were replaced by the original Dutch forms, including jantera (Sanskrit for 'wheel'), which temporarily replaced mesin (machine), ketua negara (literally 'chairman of state'), which had replaced presiden (president) and kilang (meaning 'mill'), which had replaced pabrik (factory). In a few cases, however, coinings permanently replaced earlier Dutch terms, including pajak (earlier meaning 'monopoly') instead of belasting (tax) and senam (meaning 'exercise') instead of gimnastik (gymnastics). The Komisi Bahasa is said to have coined more than 7000 terms, although few of these gained common acceptance.[10]

Adoption as the national language

The adoption of Indonesian as the country's national language was in contrast to most other post-colonial states. Neither the language with the most native speakers (Javanese) nor the language of the former European colonial power (Dutch) was to be adopted. Instead, a local language with far fewer native speakers than the most widely spoken local language was chosen (nevertheless, Malay was the second most widely spoken language in the colony after Javanese, and had many L2 speakers using it for trade, administration, and education).

In 1945, when Indonesia declared its independence, Indonesian was formally declared the national language,[8] despite being the native language of only about 5% of the population. In contrast, Javanese and Sundanese were the mother tongues of 42–48% and 15% respectively.[36] The combination of nationalistic, political, and practical concerns ultimately led to the successful adoption of Indonesian as a national language. In 1945, Javanese was easily the most prominent language in Indonesia. It was the native language of nearly half the population, the primary language of politics and economics, and the language of courtly, religious, and literary tradition.[28] What it lacked, however, was the ability to unite the diverse Indonesian population as a whole. With thousands of islands and hundreds of different languages, the newly independent country of Indonesia had to find a national language that could realistically be spoken by the majority of the population and that would not divide the nation by favouring one ethnic group, namely the Javanese, over the others. In 1945, Indonesian was already in widespread use;[36] in fact, it had been for roughly a thousand years. Over that long period, Malay, which would later become standardized as Indonesian, was the primary language of commerce and travel. It was also the language used for the propagation of Islam in the 13th to 17th centuries, as well as the language of instruction used by Portuguese and Dutch missionaries attempting to convert the indigenous people to Christianity.[28] The combination of these factors meant that the language was already known to some degree by most of the population, and it could be more easily adopted as the national language than perhaps any other. Moreover, it was the language of the sultanate of Brunei and of future Malaysia, on which some Indonesian nationalists had claims.

Over the first 53 years of Indonesian independence, the country's first two presidents, Sukarno and Suharto constantly nurtured the sense of national unity embodied by Indonesian, and the language remains an essential component of Indonesian identity. Through a language planning program that made Indonesian the language of politics, education, and nation-building in general, Indonesian became one of the few success stories of an indigenous language effectively overtaking that of a country's colonisers to become the de jure and de facto official language.[32] Today, Indonesian continues to function as the language of national identity as the Congress of Indonesian Youth envisioned, and also serves as the language of education, literacy, modernization, and social mobility.[32] Despite still being a second language to most Indonesians, it is unquestionably the language of the Indonesian nation as a whole, as it has had unrivalled success as a factor in nation-building and the strengthening of Indonesian identity.

Modern and colloquial Indonesian

Indonesian is spoken as a mother tongue and national language. Over 200 million people regularly make use of the national language, with varying degrees of proficiency. In a nation that is home to more than 700 native languages and a vast array of ethnic groups, it plays an important unifying and cross-archipelagic role for the country. Use of the national language is abundant in the media, government bodies, schools, universities, workplaces, among members of the upper-class or nobility and also in formal situations, despite the 2010 census showing only 19.94% of over-five-year-olds speak mainly Indonesian at home.[37]

Standard Indonesian is used in books and newspapers and on television/radio news broadcasts. The standard dialect, however, is rarely used in daily conversations, being confined mostly to formal settings. While this is a phenomenon common to most languages in the world (for example, spoken English does not always correspond to its written standards), the proximity of spoken Indonesian (in terms of grammar and vocabulary) to its normative form is noticeably low. This is mostly due to Indonesians combining aspects of their own local languages (e.g., Javanese, Sundanese, and Balinese) with Indonesian. This results in various vernacular varieties of Indonesian, the very types that a foreigner is most likely to hear upon arriving in any Indonesian city or town.[38] This phenomenon is amplified by the use of Indonesian slang, particularly in the cities. Unlike the relatively uniform standard variety, Vernacular Indonesian exhibits a high degree of geographical variation, though Colloquial Jakartan Indonesian functions as the de facto norm of informal language and is a popular source of influence throughout the archipelago.[16] There is language shift of first language among Indonesian into Indonesian from other language in Indonesia caused by ethnic diversity than urbanicity.[39]

The most common and widely used colloquial Indonesian is heavily influenced by the Betawi language, a Malay-based creole of Jakarta, amplified by its popularity in Indonesian popular culture in mass media and Jakarta's status as the national capital. In informal spoken Indonesian, various words are replaced with those of a less formal nature. For example, tidak (no) is often replaced with the Betawi form nggak or the even simpler gak/ga, while seperti (like, similar to) is often replaced with kayak [kajaʔ]. Sangat or amat (very), the term to express intensity, is often replaced with the Javanese-influenced banget. As for pronunciation, the diphthongs ai and au on the end of base words are typically pronounced as /e/ and /o/. In informal writing, the spelling of words is modified to reflect the actual pronunciation in a way that can be produced with less effort. For example, capai becomes cape or capek, pakai becomes pake, kalau becomes kalo. In verbs, the prefix me- is often dropped, although an initial nasal consonant is often retained, as when mengangkat becomes ngangkat (the basic word is angkat). The suffixes -kan and -i are often replaced by -in. For example, mencarikan becomes nyariin, menuruti becomes nurutin. The latter grammatical aspect is one often closely related to the Indonesian spoken in Jakarta and its surrounding areas.

Malay historical linguists agree on the likelihood of the Malay homeland being in western Borneo stretching to the Bruneian coast.[40] A form known as Proto-Malay language was spoken in Borneo at least by 1000 BCE and was, it has been argued, the ancestral language of all subsequent Malayan languages. Its ancestor, Proto-Malayo-Polynesian, a descendant of the Proto-Austronesian language, began to break up by at least 2000 BCE, possibly as a result of the southward expansion of Austronesian peoples into Maritime Southeast Asia from the island of Taiwan.[41] Indonesian, which originated from Malay, is a member of the Austronesian family of languages, which includes languages from Southeast Asia, the Pacific Ocean and Madagascar, with a smaller number in continental Asia. It has a degree of mutual intelligibility with the Malaysian standard of Malay, which is officially known there as bahasa Malaysia, despite the numerous lexical differences.[42] However, vernacular varieties spoken in Indonesia and Malaysia share limited intelligibility, which is evidenced by the fact that Malaysians have difficulties understanding Indonesian sinetron (soap opera) aired on Malaysia TV stations, and vice versa.[43]

Malagasy, a geographic outlier spoken in Madagascar in the Indian Ocean; the Philippines national language, Filipino; Formosan in Taiwan's aboriginal population; and the native Māori language of New Zealand are also members of this language family. Although each language of the family is mutually unintelligible, their similarities are rather striking. Many roots have come virtually unchanged from their common ancestor, Proto-Austronesian language. There are many cognates found in the languages' words for kinship, health, body parts and common animals. Numbers, especially, show remarkable similarities.

| Language | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAN, c. 4000 BCE | *isa | *DuSa | *telu | *Sepat | *lima | *enem | *pitu | *walu | *Siwa | *puluq |

| Malay/Indonesian | satu | dua | tiga | empat | lima | enam | tujuh | lapan/delapan | sembilan | sepuluh |

| Amis | cecay | tusa | tulu | sepat | lima | enem | pitu | falu | siwa | pulu' |

| Sundanese | hiji | dua | tilu | opat | lima | genep | tujuh | dalapan | salapan | sapuluh |

| Tsou | coni | yuso | tuyu | sʉptʉ | eimo | nomʉ | pitu | voyu | sio | maskʉ |

| Tagalog | isá | dalawá | tatló | ápat | limá | ánim | pitó | waló | siyám | sampu |

| Ilocano | maysá | dua | talló | uppát | limá | inném | pitó | waló | siam | sangapúlo |

| Cebuano | usá | Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Indonesian_language