A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

In international relations, aid (also known as international aid, overseas aid, foreign aid, economic aid or foreign assistance) is – from the perspective of governments – a voluntary transfer of resources from one country to another.

Aid may serve one or more functions: it may be given as a signal of diplomatic approval, or to strengthen a military ally, to reward a government for behavior desired by the donor, to extend the donor's cultural influence, to provide infrastructure needed by the donor for resource extraction from the recipient country, or to gain other kinds of commercial access. Countries may provide aid for further diplomatic reasons. Humanitarian and altruistic purposes are often reasons for foreign assistance.[a]

Aid may be given by individuals, private organizations, or governments. Standards delimiting exactly the types of transfers considered "aid" vary from country to country. For example, the United States government discontinued the reporting of military aid as part of its foreign aid figures in 1958.[b] The most widely used measure of aid is "Official Development Assistance" (ODA).[1]

History

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (March 2022) |

An early example of the military type of aid is the First Crusade, which began when Byzantine Greek emperor Alexios I Komnenos asked for help in defending Byzantium, the Holy Land, and the Christians living there from the Seljuk takeover of the region. The call for aid was answered by Pope Urban II, when, at the Council of Piacenza of 1095, he called for Christendom to rally in military support of the Byzantines with references to the "Greek Empire and the need of aid for it."[2]

Definitions and purpose

The Development Assistance Committee of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development defines its aid measure, Official Development Assistance (ODA), as follows: "ODA consists of flows to developing countries and multilateral institutions provided by official agencies, including state and local governments, or by their executive agencies, each transaction of which meets the following test: a) it is administered with the promotion of the economic development and welfare of developing countries as its main objective, and b) it is concessional in character and contains a grant element of at least 25% (calculated at a rate of discount of 10%)."[3][4] Foreign aid has increased since the 1950s and 1960s (Isse 129).[definition needed] The notion that foreign aid increases economic performance and generates economic growth is based on Chenery and Strout's Dual Gap Model (Isse 129). Chenerya and Strout (1966) claimed that foreign aid promotes development by adding to domestic savings as well as to foreign exchange availability, this helping to close either the savings-investment gap or the export-import gap. (Isse 129).

Carol Lancaster defines foreign aid as "a voluntary transfer of public resources, from a government to another independent government, to an NGO, or to an international organization (such as the World Bank or the UN Development Program) with at least a 25 percent grant element, one goal of which is to better the human condition in the country receiving the aid."[c]

Lancaster also states that for much of the period of her study (World War II to the present) "foreign aid was used for four main purposes: diplomatic , developmental, humanitarian relief and commercial."[d]

Extent of aid

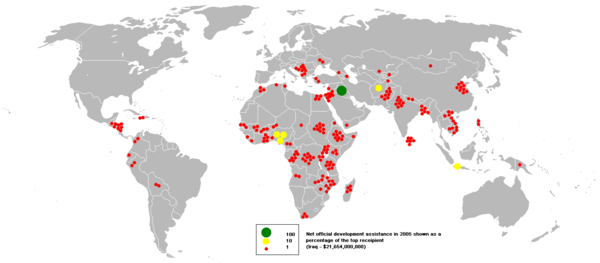

Most official development assistance (ODA) comes from the 30 members of the Development Assistance Committee (DAC),[5] or about $150 billion in 2018.[6] For the same year, the OECD estimated that six to seven billion dollars of ODA-like aid was given by ten other states, including China and India.[7]

Top 10 aid recipient countries (2009–2018)

| Country | US dollars (billions) |

|---|---|

| 51.8 | |

| 44.4 | |

| 37.9 | |

| 32.0 | |

| 28.7 | |

| 27.5 | |

| 27.4 | |

| 25.2 | |

| 24.1 |

Top 10 aid donor countries (2020)

Official development assistance (in absolute terms) contributed by the top 10 DAC countries is as follows. European Union countries together gave $75,838,040,000 and EU Institutions gave a further $19.4 billion.[9][10] The European Union accumulated a higher portion of GDP as a form of foreign aid than any other economic union.[11]

European Union – $75.8 billion

European Union – $75.8 billion

United States – $34.6 billion

United States – $34.6 billion Germany – $23.8 billion

Germany – $23.8 billion United Kingdom – $19.4 billion

United Kingdom – $19.4 billion Japan – $15.5 billion

Japan – $15.5 billion France – $12.2 billion

France – $12.2 billion Sweden – $5.4 billion

Sweden – $5.4 billion Netherlands – $5.3 billion

Netherlands – $5.3 billion Italy – $4.9 billion

Italy – $4.9 billion Canada – $4.7 billion

Canada – $4.7 billion Norway – $4.3 billion

Norway – $4.3 billion

Official development assistance as a percentage of gross national income contributed by the top 10 DAC countries is as follows. Five countries met the longstanding UN target for an ODA/GNI ratio of 0.7% in 2013:[9]

Norway – 1.07%

Norway – 1.07% Sweden – 1.02%

Sweden – 1.02% Luxembourg – 1.00%

Luxembourg – 1.00% Denmark – 0.85%

Denmark – 0.85% United Kingdom – 0.72%

United Kingdom – 0.72% Netherlands – 0.67%

Netherlands – 0.67% Finland – 0.55%

Finland – 0.55% Switzerland – 0.47%

Switzerland – 0.47% Belgium – 0.45%

Belgium – 0.45% Ireland – 0.45%

Ireland – 0.45%

European Union countries that are members of the Development Assistance Committee gave 0.42% of GNI (excluding the $15.93 billion given by EU Institutions).[9]

Arab countries as "New Donors"

The mid-1970s saw some new emerging donors in the face of the world crises, discovery of oil, the impending Cold War. While in many literature they are popularly called the 'new donors', they are by no means new. In the sense, that the former USSR had been contributing to the popular Aswan Dam in Egypt as early as 1950s or India and other Asian countries were known for their assistance under the Colombo Plan [12] Of these the Arab countries in particularly have been quite influential. Kuwait, Saudi Arabi and United Arab Emirates are the top donors in this sense. The aid from Arab countries are often less documented for the fact that they do not follow the standard aid definitions of the OECD and DAC countries. Many times, the aid from Arab countries are made by private funds owned by the families of the monarch. Many Arab recipient countries have also avoided of speaking on aid openly in order to digress from the idea of hierarchy of Eurocentrism and Wester-centrism, which are in some ways reminders of the colonial pasts.[13] Hence, the classification of such transfers are tricky[14]

Over and on top of this, there has been extensive research that Arab aid is often allocated initially to Arab countries, and perhaps recently to some sub-Saharan African countries which have shown Afro-Arab unity. This is especially true considering the fact that aid by Arab donors is more geographically concentrated, given without conditionality and often to poorest nations in the Middle East and North Africa.[15] This is perhaps potentially due to the existence of Arab Fund for Technical Assistance to African and Arab Countries (AFTAAAC) or the Arab Bank for Economic Development in Africa (BADEA).[16] OECD data for example also shows Arab countries donate more to lower middle income countries, contrast to the DAC donors. It is not completely clear why such a bias must exists, but some studies have studied the sectoral donations.[17]

Another big difference between the traditional DAC (Western) donors and the Arab donors is that Arab donors give aid unconditionally. Typically they have followed a rule of non-interference in the policy of the recipient. The Arab approach is limited to giving advice on policy matters when they discover clear failures. This kind of view is often repeated in many studies.[18]These kind of approach has always been problematic for the relationship Arab countries have with institutions like IMF, World Bank etc., since Arab countries are members of these institutions and in some ways they oppose the conditionality guidelines for granting aid and conditions on repayment agreed internationally.[19] More recently, UAE has been declaring its aid flows with the IMF and OECD.[20] Data from this reveals that potential opacity in declaring aid may also result from the fact some Arab countries do not want to be seen openly as supporters of a cause or a proxy group in a neighboring country or region. The exact impact of such bilateral aid is difficult to discern.

Arab aid has often been used a tool for steering foreign policy. The 1990 Iraq invasion of Kuwait triggered an increase of Arab aid and large amounts went to countries which supported Kuwait. Many countries around this time still kept supporting Iraq, despite rallying against the war. This lead the Kuwait national assembly to decide to deny aid to supporters of Iraq. Saudi Arabia for example did a similar thing, In 1991, after the war, countries against Iraq –Egypt, Turkey and Morocco became the three major aid recipients of Saudi aid.[21]Several similar stances have arisen in the recent years after the Arab Spring of 2011 particularly.

Types

This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2021) |

The type of aid given may be classified according to various factors, including its intended purpose, the terms or conditions (if any) under which it is given, its source, and its level of urgency.

Intended purpose

Official aid may be classified by types according to its intended purpose. Military aid is material or logistical assistance given to strengthen the military capabilities of an ally country.[22] Humanitarian aid is material or logistical assistance provided for humanitarian purposes, typically in response to humanitarian crises such as a natural disaster or a man-made disaster.[23]

Terms or conditions of receipt

Aid can also be classified according to the terms agreed upon by the donor and receiving countries. In this classification, aid can be a gift, a grant, a low or no interest loan, or a combination of these. The terms of foreign aid are oftentimes influenced by the motives of the giver: a sign of diplomatic approval, to reward a government for behaviour desired by the donor, to extend the donor's cultural influence, to enhance infrastructure needed by the donor for the extraction of resources from the recipient country, or to gain other kinds of commercial access.[a]

Sources

Aid can also be classified according to its source. While government aid is generally called foreign aid, aid that originates in institutions of a religious nature is often termed faith-based foreign aid (some examples are, Salvation Army, Catholic Relief Services, etc).[24] Aid from various sources can reach recipients through bilateral or multilateral delivery systems. "Bilateral" refers to government to government transfers. "Multilateral" institutions, such as the World Bank or UNICEF, pool aid from one or more sources and disperse it among many recipients.

International aid in the form of gifts by individuals or businesses (aka, "private giving") are generally administered by charities or philanthropic organizations who batch them and then channel these to the recipient country.

Urgency

Aid may be also classified based on urgency into emergency aid and development aid. Emergency aid is rapid assistance given to a people in immediate distress by individuals, organizations, or governments to relieve suffering, during and after man-made emergencies (like wars) and natural disasters. The term often carries an international connotation, but this is not always the case. It is often distinguished from development aid by being focused on relieving suffering caused by natural disaster or conflict, rather than removing the root causes of poverty or vulnerability. Development aid is aid given to support development in general which can be economic development or social development in developing countries. It is distinguished from humanitarian aid as being aimed at alleviating poverty in the long term, rather than alleviating suffering in the short term.

Emergency aid

The provision of emergency humanitarian aid consists of the provision of vital services (such as food aid to prevent starvation) by aid agencies, and the provision of funding or in-kind services (like logistics or transport), usually through aid agencies or the government of the affected country. Humanitarian aid is distinguished from humanitarian intervention, which involves armed forces protecting civilians from violent oppression or genocide by state-supported actors.

The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) is mandated to coordinate the international humanitarian response to a natural disaster or complex emergency acting on the basis of the United Nations General Assembly Resolution 46/182.[25] The Geneva Conventions give a mandate to the International Committee of the Red Cross and other impartial humanitarian organizations to provide assistance and protection of civilians during times of war. The ICRC, has been given a special role by the Geneva Conventions with respect to the visiting and monitoring of prisoners of war.

Development aid

Development aid is given by governments through individual countries' international aid agencies and through multilateral institutions such as the World Bank, and by individuals through development charities. For donor nations, development aid also has strategic value;[26] improved living conditions can positively effects global security and economic growth. Official Development Assistance (ODA) is a commonly used measure of developmental aid.

Intended use

Aid given is generally intended for use by a specific end. From this perspective it may be called:

- Project aid: Aid given for a specific purpose; e.g. building materials for a new school.

- Programme aid: Aid given for a specific sector; e.g. funding of the education sector of a country.

- Budget support: A form of Programme Aid that is directly channelled into the financial system of the recipient country.

- Sector-wide Approaches (SWAPs): A combination of Project aid and Programme aid/Budget Support; e.g. support for the education sector in a country will include both funding of education projects (like school buildings) and provide funds to maintain them (like school books).

- Technical assistance: Aid involving highly educated or trained personnel, such as doctors, who are moved into a developing country to assist with a program of development. Can be both programme and project aid.

- Food aid: Food is given to countries in urgent need of food supplies, especially if they have just experienced a natural disaster. Food aid can be provided by importing food from the donor, buying food locally, or providing cash.

- International research, such as research that used for the green revolution or vaccines.

Official development assistance

This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2021) |

Official development assistance (ODA) is a term coined by the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) to measure aid. ODA refers to aid from national governments for promoting economic development and welfare in low and middle income countries.[27] ODA can be bilateral or multilateral. This aid is given as either grants, where no repayment is required, or as concessional loans, where interest rates are lower than market rates.[e]

Loan repayments to multilateral institutions are pooled and redistributed as new loans. Additionally, debt relief, partial or total cancellation of loan repayments, is often added to total aid numbers even though it is not an actual transfer of funds. It is compiled by the Development Assistance Committee. The United Nations, the World Bank, and many scholars use the DAC's ODA figure as their main aid figure because it is easily available and reasonably consistently calculated over time and between countries.[e][28] The DAC classifies aid in three categories:

- Official Development Assistance (ODA): Development aid provided to developing countries (on the "Part I" list) and international organizations with the clear aim of economic development.[29]

- Official Aid (OD): Development aid provided to developed countries (on the "Part II" list).

- Other Official Flows (OOF): Aid which does not fall into the other two categories, either because it is not aimed at development, or it consists of more than 75% loan (rather than grant).

Aid is often pledged at one point in time, but disbursements (financial transfers) might not arrive until later.

In 2009, South Korea became the first major recipient of ODA from the OECD to turn into a major donor. The country now provides over $1 billion in aid annually.[30]

Not included as international aid

Most monetary flows between nations are not counted as aid. These include market-based flows such as foreign direct investments and portfolio investments, remittances from migrant workers to their families in their home countries, and military aid. In 2009, aid in the form of remittances by migrant workers in the United States to their international families was twice as large as that country's humanitarian aid.[31] The World Bank reported that, worldwide, foreign workers sent $328 billion from richer to poorer countries in 2008, over twice as much as official aid flows from OECD members.[31] The United States does not count military aid in its foreign aid figures.[32]

Improving aid effectiveness

The High Level Forum is a gathering of aid officials and representatives of donor and recipient countries. Its Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness outlines rules to improve the quality of aid.

Conditionalities

A major proportion of aid from donor nations is tied, mandating that a receiving nation spend on products and expertise originating only from the donor country. [33] Eritrea discovered that it would be cheaper to build its network of railways with local expertise and resources rather than to spend aid money on foreign consultants and engineers.[33] US law, backed by strong farm interests,[34] requires food aid be spent on buying food from the US rather than locally, and, as a result, half of what is spent is used on transport.[35] As a result, tying aid is estimated to increase the cost of aid by 15–30%.[36] Oxfam America and American Jewish World Service report that reforming US food aid programs could extend food aid to an additional 17.1 million people around the world.[37]

The World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, as primary holders of developing countries' debt, attach structural adjustment conditionalities to loans which generally include the elimination of state subsidies and the privatization of state services. For example, the World Bank presses poor nations to eliminate subsidies for fertilizer even while many farmers cannot afford them at market prices.[38] In the case of Malawi, almost five million of its 13 million people used to need emergency food aid. However, after the government changed policy and subsidies for fertilizer and seed were introduced, farmers produced record-breaking corn harvests in 2006 and 2007 as production leaped to 3.4 million in 2007 from 1.2 million in 2005, making Malawi a major food exporter.[38] In the former Soviet states, the reconfiguration of public financing in their transition to a market economy called for reduced spending on health and education, sharply increasing poverty.[39][40][41]

In their April 2002 publication, Oxfam Report reveals that aid tied to trade liberalization by the donor countries such as the European Union with the aim of achieving economic objective is becoming detrimental to developing countries.[42] For example, the EU subsidizes its agricultural sectors in the expense of Latin America who must liberalize trade in order to qualify for aid. Latin America, a region with a comparative advantage on agriculture and a great reliance on its agricultural export sector, loses $4 billion annually due to EU farming subsidy policies. Carlos Santiso advocates a "radical approach in which donors cede control to the recipient country".[43]

Cash aid versus in-kind aid

A report by a High Level Panel on Humanitarian Cash Transfers found that only 6% of aid is delivered in the form of cash or vouchers.[44] But there is a growing realization among aid groups that, for locally available goods, giving cash or cash vouchers instead of imported goods is a cheaper, faster, and more efficient way to deliver aid.[45]

Evidence shows that cash can be more transparent, more accountable, more cost effective, help support local markets and economies, and increase financial inclusion and give people more dignity and choice.[44] Sending cash is cheaper as it does not have the same transaction costs as shipping goods. Sending cash is also faster than shipping the goods. In 2009 for sub-Saharan Africa, food bought locally by the WFP cost 34 percent less and arrived 100 days faster than food sent from the United States, where buying food from the United States is required by law.[46] Cash aid also helps local food producers, usually the poorest in their countries, while imported food may damage their livelihoods and risk continuing hunger in the future.[46] Unconditional cash transfers, for example, appear to be an effective intervention for reducing extreme poverty, while at the same time also improving health and education outcomes.[47][48]

The World Food Program (WFP), the biggest non-governmental distributor of food, announced that it will begin distributing cash and vouchers instead of food in some areas, which Josette Sheeran, the WFP's executive director, described as a "revolution" in food aid.[45][49]

Coordination

While the number of Non-governmental Organization have increased dramatically over the past few decades, fragmentation in aid policy is an issue.[36] Because of such fragmentation, health workers in several African countries, for example, say they are so busy meeting western delegates that they can only do their proper jobs in the evening.[36]

One of the Paris Declaration's priorities is to reduce systems of aid that are "parallel" to local systems.[36] For example, Oxfam reported that, in Mozambique, donors are spending $350 million a year on 3,500 technical consultants, which is enough to hire 400,000 local civil servants, weakening local capacity.[36] Between 2005 and 2007, the number of parallel systems did fall, by about 10% in 33 countries.[36] In order to improve coordination and reduce parallel systems, the Paris Declaration suggests that aid recipient countries lay down a set of national development priorities and that aid donors fit in with those plans.[36]

Aid priorities

Laurie Garret, author of the article "The Challenge of Global Health" points out that the current aid and resources are being targeted at very specific, high-profile diseases, rather than at general public health. Aid is "stovepiped" towards narrow, short-term goals relating to particular programs or diseases such as increasing the number of people receiving anti-retroviral treatment, and increasing distribution of bed nets. These are band aid solutions to larger problems, as it takes healthcare systems and infrastructure to create significant change. Donors lack the understanding that effort should be focused on broader measures that affect general well-being of the population, and substantial change will take generations to achieve. Aid often does not provide maximum benefit to the recipient, and reflects the interests of the donor.[50]

Furthermore, consider the breakdown, where aid goes and for what purposes. In 2002, total gross foreign aid to all developing countries was $76 billion. Dollars that do not contribute to a country's ability to support basic needs interventions are subtracted. Subtract $6 billion for debt relief grants. Subtract $11 billion, which is the amount developing countries paid to developed nations in that year in the form of loan repayments. Next, subtract the aid given to middle income countries, $16 billion. The remainder, $43 billion, is the amount that developing countries received in 2002. But only $12 billion went to low-income countries in a form that could be deemed budget support for basic needs.[51] When aid is given to the Least Developed Countries who have good governments and strategic plans for the aid, it is thought that it is more effective.[51]

Logistics

Humanitarian aid is argued to often not reach those who are intended to receive it. For example, a report composed by the World Bank in 2006 stated that an estimated half of the funds donated towards health programs in sub-Saharan Africa did not reach the clinics and hospitals. Money is paid out to fake accounts, prices are increased for transport or warehousing, and drugs are sold to the black market. Another example is in Ghana, where approximately 80% of donations do not go towards their intended purposes. This type of corruption only adds to the criticism of aid, as it is not helping those who need it, and may be adding to the problem.[50] Only about one fifth of U.S. aid goes to countries classified by the OECD as 'least developed.'[52] This "pro-rich" trend is not unique to the United States.[51][52] According to Collier, "the middle income countries get aid because they are of much more commercial and political interest than the tiny markets and powerlessness of the bottom billion."[53] What this means is that, at the most basic level, aid is not targeting the most extreme poverty.[51][52]

The logistics in which the delivery of humanitarian occurs can be problematic. For example, an earthquake in 2003 in Bam, Iran left tens of thousands of people in need of disaster zone aid. Although aid was flown in rapidly, regional belief systems, cultural backgrounds and even language seemed to have been omitted as a source of concern. Items such as religiously prohibited pork, and non-generic forms of medicine that lacked multilingual instructions came flooding in as relief. An implementation of aid can easily be problematic, causing more problems than it solves.[54]

Considering transparency, the amount of aid that is recorded accurately has risen from 42% in 2005 to 48% in 2007.[36]

Improving the economic efficiency of aidedit

Currently, donor institutions make proposals for aid packages to recipient countries. The recipient countries then make a plan for how to use the aid based on how much money has been given to them. Alternatively, NGO's receive funding from private sources or the government and then implement plans to address their specific issues. According to Sachs, in the view of some scholars, this system is inherently ineffective.[51]

According to Sachs, we should redefine how we think of aid. The first step should be to learn what developing countries hope to accomplish and how much money they need to accomplish those goals. Goals should be made with the Millennium Development Goals in mind for these furnish real metrics for providing basic needs. The "actual transfer of funds must be based on rigorous, country-specific plans that are developed through open and consultative processes, backed by good governance in the recipient countries, as well as careful planning and evaluation."[51]

Possibilities are also emerging as some developing countries are experiencing rapid economic growth, they are able to provide their own expertise gained from their recent transition. This knowledge transfer can be seen in donors, such as Brazil, whose $1 billion in aid outstrips that of many traditional donors.[55] Brazil provides most of its aid in the form of technical expertise and knowledge transfers.[55] This has been described by some observers as a 'global model in waiting'.[56]

Criticismedit

This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2021) |

Statistical studies have produced widely differing assessments of the correlation between aid and economic growth: there is little consensus with some studies finding a positive correlation[57] while others find either no correlation or a negative correlation.[58] One consistent finding is that project aid tends to cluster in richer parts of countries, meaning most aid is not given to poor countries or poor recipients.[59] In the case of Africa, Asante (1985) gives the following assessment:

Summing up the experience of African countries both at the national and at the regional levels it is no exaggeration to suggest that, on balance, foreign assistance, especially foreign capitalism, has been somewhat deleterious to African development. It must be admitted, however, that the pattern of development is complex and the effect upon it of foreign assistance is still not clearly determined. But the limited evidence available suggests that the forms in which foreign resources have been extended to Africa over the past twenty-five years, insofar as they are concerned with economic development, are, to a great extent, counterproductive.[f]

Peter Singer argues that over the last three decades, "aid has added around one percentage point to the annual growth rate of the bottom billion." He argues that this has made the difference between "stagnation and severe cumulative decline."[52] Aid can make progress towards reducing poverty worldwide, or at least help prevent cumulative decline. Despite the intense criticism on aid, there are some promising numbers. In 1990, approximately 43 percent of the world's population was living on less than $1.25 a day and has dropped to about 16 percent in 2008. Maternal deaths have dropped from 543,000 in 1990 to 287,000 in 2010. Under-five mortality rates have also dropped, from 12 million in 1990 to 6.9 million in 2011.[60] Although these numbers alone sound promising, there is a gray overcast: many of these numbers actually are falling short of the Millennium Development Goals. There are only a few goals that have already been met or projected to be met by the 2015 deadline.

The economist William Easterly and others have argued that aid can often distort incentives in poor countries in various harmful ways. Aid can also involve inflows of money to poor countries that have some similarities to inflows of money from natural resources that provoke the resource curse.[61][62] This is partially because aid given in the form of foreign currency causes exchange rate to become less competitive and this impedes the growth of manufacturing sector which is more conducive in the cheap labour conditions. Aid also can take the pressure off and delay the painful changes required in the economy to shift from agriculture to manufacturing.[63]

Some believe that aid is offset by other economic programs such as agricultural subsidies. Mark Malloch Brown, former head of the United Nations Development Program, estimated that farm subsidies cost poor countries about US$50 billion a year in lost agricultural exports:

It is the extraordinary distortion of global trade, where the West spends $360 billion a year on protecting its agriculture with a network of subsidies and tariffs that costs developing countries about US$50 billion in potential lost agricultural exports. Fifty billion dollars is the equivalent of today's level of development assistance.[64][65]

Some have argued that the major international aid organizations have formed an aid cartel.[66]

In response to aid critics, a movement to reform U.S. foreign aid has started to gain momentum. In the United States, leaders of this movement include the Center for Global Development, Oxfam America, the Brookings Institution, InterAction, and Bread for the World. The various organizations have united to call for a new Foreign Assistance Act, a national development strategy, and a new cabinet-level department for development.[67]

In November 2012, a spoof charity music video was produced by a South African rapper named Breezy V. The video "Africa for Norway" promoting "Radi-Aid" was a parody of Western charity initiatives like Band Aid which, he felt, exclusively encouraged small donations to starving children, creating a stereotypically negative view of the continent.[68] Aid in his opinion should be about funding initiatives and projects with emotional motivation as well as money. The parody video shows Africans getting together to campaign for Norwegian people suffering from frostbite by supplying them with unwanted radiators.[68]

Anthropologist and researcher Jason Hickel concludes from a 2016 report[69] by the US-based Global Financial Integrity (GFI) and the Centre for Applied Research at the Norwegian School of Economics that

the usual development narrative has it backwards. Aid is effectively flowing in reverse. Rich countries aren't developing poor countries; poor countries are developing rich ones... The aid narrative begins to seem a bit naïve when we take these reverse flows into account. It becomes clear that aid does little but mask the maldistribution of resources around the world. It makes the takers seem like givers, granting them a kind of moral high ground while preventing those of us who care about global poverty from understanding how the system really works.[70]

Unintended consequencesedit

Some of the unintended effects include labor and production disincentives, changes in recipients' food consumption patterns and natural resources use patterns, distortion of social safety nets, distortion of NGO operational activities, price changes, and trade displacement. These issues arise from targeting inefficacy and poor timing of aid programs. Food aid can harm producers by driving down prices of local products, whereas the producers are not themselves beneficiaries of food aid. Unintentional harm occurs when food aid arrives or is purchased at the wrong time, when food aid distribution is not well-targeted to food-insecure households, and when the local market is relatively poorly integrated with broader national, regional and global markets. The use of food aid for emergencies can reduce the unintended consequences, although it can contribute to other associated with the use of food as a weapon or prolonging or intensifying the duration of civil conflicts. Also, aid attached to institution building and democratization can often result in the consolidation of autocratic governments when effective monitoring is absent.[71]

Increasing conflict durationedit

International aid organizations identify theft by armed forces on the ground as a primary unintended consequence through which food aid and other types of humanitarian aid promote conflict. Food aid usually has to be transported across large geographic territories and during the transportation it becomes a target for armed forces, especially in countries where the ruling government has limited control outside of the capital. Accounts from Somalia in the early 1990s indicate that between 20 and 80 percent of all food aid was stolen, looted, or confiscated.[72] In the former Yugoslavia, the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) lost up to 30 percent of the total value of aid to Serbian armed forces. On top of that 30 percent, bribes were given to Croatian forces to pass their roadblocks in order to reach Bosnia.[73]

The value of the stolen or lost provisions can exceed the value of the food aid alone since convoy vehicles and telecommunication equipment are also stolen. MSF Holland, international aid organization operating in Chad and Darfur, underscored the strategic importance of these goods, stating that these "vehicles and communications equipment have a value beyond their monetary worth for armed actors, increasing their capacity to wage war"[73]

A famous instance of humanitarian aid unintentionally helping rebel groups occurred during the Nigeria-Biafra civil war in the late 1960s,[74] where the rebel leader Odumegwu Ojukwu only allowed aid to enter the region of Biafra if it was shipped on his planes. These shipments of humanitarian aid helped the rebel leader to circumvent the siege on Biafra placed by the Nigerian government. These stolen shipments of humanitarian aid caused the Biafran civil war to last years longer than it would have without the aid, claim experts.[73]

The most well-known instances of aid being seized by local warlords in recent years come from Somalia, where food aid is funneled to the Shabab, a Somali militant group that controls much of Southern Somalia. Moreover, reports reveal that Somali contractors for aid agencies have formed a cartel and act as important power brokers, arming opposition groups with the profits made from the stolen aid"[75]

Rwandan government appropriation of food aid in the early 1990s was so problematic that aid shipments were canceled multiple times.[76] In Zimbabwe in 2003, Human Rights Watch documented examples of residents being forced to display ZANU-PF Party membership cards before being given government food aid.[77] In eastern Zaire, leaders of the Hema ethnic group allowed the arrival of international aid organizations only upon agreement not give aid to the Lendu (opposition of Hema). Humanitarian aid workers have acknowledged the threat of stolen aid and have developed strategies for minimizing the amount of theft en route. However, aid can fuel conflict even if successfully delivered to the intended population as the recipient populations often include members of rebel groups or militia groups, or aid is "taxed" by such groups.

Academic research emphatically demonstrates that on average food aid promotes civil conflict. Namely, increase in US food aid leads to an increase in the incidence of armed civil conflict in the recipient country.[72] Another correlation demonstrated is food aid prolonging existing conflicts, specifically among countries with a recent history of civil conflict. However, this does not find an effect on conflict in countries without a recent history of civil conflict.[72] Moreover, different types of international aid other than food which is easily stolen during its delivery, namely technical assistance and cash transfers, can have different effects on civil conflict.

Community-driven development (CDD) programs have become one of the most popular tools for delivering development aid. In 2012, the World Bank supported 400 CDD programs in 94 countries, valued at US$30 billion.[78] Academic research scrutinizes the effect of community-driven development programs on civil conflict.[79] The Philippines' flagship development program KALAHI-CIDSS is concluded to have led to an increase in violent conflict in the country. After the program's start, some municipalities experienced and statistically significant and large increase in casualties, as compared to other municipalities who were not part of the CDD. Casualties suffered by government forces as a result of insurgent-initiated attacks increased significantly.

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=International_aid

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk