A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Chinese characters | |

|---|---|

"Chinese character" written in traditional (left) and simplified (right) forms | |

| Script type | Logographic

|

Time period | c. 13th century BCE – present |

| Direction |

|

| Languages | (among others) |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | (Proto-writing)

|

Child systems | |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Hani (500), Han (Hanzi, Kanji, Hanja) |

| Unicode | |

Unicode alias | Han |

| U+4E00–U+9FFF CJK Unified Ideographs (full list) | |

| Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 汉字 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 漢字 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Han characters | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese alphabet |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hán-Nôm |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chữ Hán | 漢字 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Zhuang name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Zhuang |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 한자 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 漢字 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 漢字 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Chinese characters[a] are logographs used to write the Chinese languages and others from regions historically influenced by Chinese culture. Chinese characters have a documented history spanning over three millennia, representing one of the four independent inventions of writing accepted by scholars; of these, they comprise the only writing system continuously used since its invention. Over time, the function, style, and means of writing characters have evolved greatly. Informed by a long tradition of lexicography, modern states using Chinese characters have standardised their forms and pronunciations: broadly, simplified characters are used to write Chinese in mainland China, Singapore, and Malaysia, while traditional characters are used in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macau.

After being introduced to other countries in order to write Literary Chinese, characters were eventually adapted to write the local languages spoken throughout the Sinosphere. In Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese, Chinese characters are known as kanji, hanja, and chữ Hán respectively. Each of these countries used existing characters to write both native and Sino-Xenic vocabulary, and created new characters for their own use. These languages each belong to separate language families, and generally function differently from Chinese. This has contributed to Chinese characters largely being replaced with alphabets in Korean and Vietnamese, leaving Japanese as the only major non-Chinese language still written with Chinese characters.

Unlike in alphabets, where letters correspond to a language's units of sound, called phonemes—Chinese characters correspond to morphemes, a language's smallest units of meaning. Morphemes in Chinese are usually a single syllable in length, but characters may represent morphemes comprising multiple syllables as well. Chinese characters are not ideographs, as they correspond to the morphemes of a particular language, but not the abstracted ideas themselves. While phonetic writing is thought to have been derived from logographic writing in all historical cases, Chinese characters are the only logographs still widely used to read and write. Most characters are made of smaller components that may provide information regarding the character's meaning or pronunciation.

Development

Chinese characters are accepted as representing one of four independent inventions of writing in human history.[b] In each instance, writing evolved from a system using two distinct types of ideographs. Ideographs could either be pictographs visually depicting objects or concepts, or fixed signs representing concepts only by shared convention. These systems are classified as proto-writing, because the techniques they used were insufficient to carry the meaning of spoken language by themselves.[3]

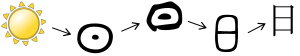

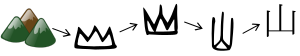

Various innovations were required for Chinese characters to emerge from proto-writing. Firstly, pictographs became distinct from simple pictures in use and appearance: for example, the pictograph 大, meaning 'large', was originally a picture of a large man, but one would need to be aware of its specific meaning in order to interpret the sequence 大鹿 as signifying 'large deer', rather than being a picture of a large man and a deer next to one another. Due to this process of abstraction, as well as to make characters easier to write, pictographs gradually became more simplified and regularised—often to the extent that the original objects represented are no longer obvious.[4]

This proto-writing system was limited to representing a relatively narrow range of ideas with a comparatively small library of symbols. This compelled innovations that allowed for symbols to directly encode spoken language.[5] In each historical case, this was accomplished by some form of the rebus technique, where the symbol for a word is used to indicate a different word with a similar pronunciation, depending on context. This allowed for words that lacked a plausible pictographic representation to be written down for the first time. This technique pre-empted more sophisticated methods of character creation that would further expand the lexicon. The process whereby writing emerged from proto-writing took place over a long period; when the purely pictorial use of symbols disappeared, leaving only those representing spoken words, the process was complete.[6]

Classification

Chinese characters have been used in several different writing systems throughout history. The concept of a writing system includes the written symbols that are used, called graphemes—these may include characters, numerals, or punctuation—as well as the rules by which the graphemes are used to record language.[7] Chinese characters are logographs, graphemes that denote words or morphemes in a language. Writing systems that use logographs are contrasted with alphabets and syllabaries, where graphemes correspond to the phonetic units in a language.[8] In special cases characters may correspond to non-morphemic syllables; due to this, written Chinese is often characterised as morphosyllabic.[9][c]

The Sinosphere has a long tradition of lexicography attempting to explain and refine the use of characters; for most of history, analysis revolved around a model first popularised in the 2nd-century Shuowen Jiezi dictionary.[11] Newer models have since appeared, often attempting to describe both the methods by which characters were created, the characteristics of their structures, and the way they presently function.[12]

Structural analysis

Most characters can be analysed structurally as compounds made of smaller components (偏旁; piānpáng), which may have their own functions. Phonetic components provide a hint to a character's pronunciation, and semantic components indicate some element of the character's meaning. Components that serve neither function may be classified as pure signs with no particular meaning, other than their presence distinguishing one character from another.[13]

A straightforward structural classification scheme may consist of three pure classes of semantographs, phonographs and signs—having only semantic, phonetic, and form components respectively, as well as four classes corresponding to each possible combination of the three component types.[14] According to Yang Runlu, of the 3,500 characters used frequently in Standard Chinese, pure semantographs are the rarest, accounting for about 5% of the lexicon, followed by pure signs with 18%, and semantic–form and phonetic–form compounds together accounting for 19%. The remaining 58% are phono-semantic compounds.[15]

The Chinese palaeographer Qiu Xigui (b. 1935) presents "three principles" of character formation adapted from an earlier proposal by Tang Lan (1901–1979), with semantographs describing all characters whose forms are wholly related to their meaning, regardless of the method by which the meaning was originally depicted, phonographs that include a phonetic component, and loangraphs encompassing existing characters that have been borrowed to write other words. Qiu also acknowledges the existence of character classes that fall outside of these principles, such as pure signs.[16]

Semantographs

Pictographs

While relatively few in number, many of the earliest characters were pictographs (象形; xiàngxíng), representational pictures of physical objects.[17] In practice, their forms have become regularised and simplified after centuries of iteration in order to make them easier to write. Examples include 日 ('Sun'), 月 ('Moon'), and 木 ('tree').[A]

As character forms developed, distinct depictions of various physical objects within pictographs became reduced to instances of a single written component.[18] As such, what a pictograph is depicting is often not immediately evident, and may be considered as a pure sign without regard for its origin in picture-writing. However, if a character's use in compounds, such as 日 in 晴 ('clear sky') still reflects its meaning and is not phonetic or arbitrary, it can still be considered as a semantic component.[19]

Due to the regularisation of character forms, individualised components may form part of a compound pictograph. For example, within a given character the component ⼝ 'MOUTH' often carries a meaning related to mouths, but within 高 ('tall')—a pictograph of a tall building—it instead depicts a window, ultimately lending to the character's meaning of 'tallness'. In another instance, the same 'MOUTH' component depicts the lip of a vessel in the modern form of the pictograph 畐 ('full').[B]

Pictographs have often been extended from their original concrete meanings to take on additional layers of metaphor and synecdoche, which sometimes even displace the pictograph's original meaning. Historically, this process has sometimes created excess ambiguity between different senses of a character, which is usually then resolved by deriving new compound characters by adding components corresponding to specific senses. This can result in new pictographs, but usually results in other character types.[20]

Indicatives

Indicatives (指事; zhǐshì), also called simple ideographs, represent abstract concepts that lack concrete physical forms, but nonetheless can be visually depicted in an intuitive way. Examples include 上 ('up') and 下 ('down')—these characters originally had forms consisting of dots placed above and below a line, which later evolved into their present forms, which have less potential for graphical ambiguity in context.[21] More complex indicatives include 凸 ('convex'), 凹 ('concave'), and 平 ('flat and level').[22]

Compound ideographs

Compound ideographs (会意; 會意; huìyì)—also called logical aggregates, associative idea characters, or syssemantographs—juxtapose multiple pictographs or indicatives to suggest a new, synthetic meaning. A canonical example is 明 ('bright'), interpreted as the juxtaposition of the two brightest objects in the sky: ⽇ 'SUN' and ⽉ 'MOON', together expressing their shared quality of brightness. Though the historicity of this etymology has been contested in recent scholarship, it is a canonical reading. Other examples include 休 ('rest'), composed of pictographs ⼈ 'MAN' and ⽊ 'TREE', and 好 ('good'), composed of ⼥ 'WOMAN' and ⼦ 'CHILD'.[C][23]

Many traditional examples of compound ideographs are now believed to have actually originated as phono-semantic compounds, made obscure by subsequent changes in pronunciation.[24] For example, the Shuowen Jiezi describes 信 ('trust') as an ideographic compound of ⼈ 'MAN' and ⾔ 'SPEECH', but modern analyses instead identify it as a phono-semantic compound—though with disagreement as to which component is phonetic.[25] Peter A. Boodberg and William G. Boltz go so far as to deny that any compound ideographs were devised in antiquity, maintaining that secondary readings that are now lost are responsible for the apparent absence of phonetic indicators,[26] but their arguments have been rejected by other scholars.[27] Compound ideographs are common in kokuji, characters originally coined in Japan.[28]

Phonographs

Phono-semantic compounds

Phono-semantic compounds (形声; 形聲; xíngshēng) are composed of at least one semantic component and one phonetic component.[29] They may be formed by one of several methods, often by adding a phonetic component to disambiguate a loangraph, or by adding a semantic component to represent a specific extension of a character's meaning.[30] Examples of phono-semantic compounds include 河 (hé; 'river'), 湖 (hú; 'lake'), 流 (liú; 'stream'), 沖 (chōng; 'surge'), and 滑 (huá; 'slippery'). Each of these characters have three short strokes on their left-hand side: 氵, a component that is a reduced form of ⽔ ('water'). In these characters, the component serves a semantic function, indicating the character has some meaning related to water. The remainder of each is a phonetic component: 湖 (hú) is pronounced identically to 胡 (hú) in Standard Chinese, 河 (hé) is pronounced similarly to 可 (kě), and 沖 (chōng) is pronounced similarly to 中 (zhōng).[d]

While they may sometimes indicate a character's pronunciation exactly, the phonetic components of most compounds only attempt to provide an approximation—even before any subsequent sound shifts take place within the spoken language. Some characters may only have the same initial or final sound of a syllable in common with phonetic components.[33] The table below lists characters that each use 也 for their phonetic part—save the final one, which uses a previous character in the list—it is apparent that none of them share its modern pronunciation. The Old Chinese pronunciation of 也 has been reconstructed by Baxter and Sagart (2014) as /*lAjʔ/, similar to that for each compound.[34] The table illustrates the sound changes that have taken place since the Shang and Zhou dynasties, when most of the characters in question entered the lexicon. The resulting drift is illustrative of the more extreme cases, when a character's phonetic component no longer provides any hint of its pronunciation.[35]

| Char. | Gloss | Component | OC[α] | MC[β] | Modern[γ] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sem. | Phon. | Mandarin | Cantonese | Japanese | ||||

| 也 | PTC | —[e] | /*lAjʔ/ | yaeX | yě | jaa5 | ya [ja̠] | |

| 池 | 'pool' |

|

|

/*Cə.lraj/ | drje | chí | ci4 | chi [tɕi] |

| 馳 | 'gallop' |

|

/*raj/ | |||||

| 弛 | 'loosen' |

|

/*l̥ajʔ/ | syeX | chí shǐ |

ci4 | chi [tɕi] shi [ɕi] | |

| 施 | 'set up' |

|

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Chinese_character||||||