A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

Bayonne, New Jersey | |

|---|---|

The Bayonne Bridge in May 2019 | |

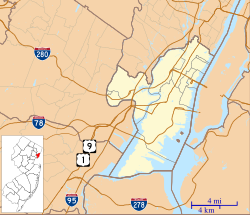

Interactive map of Bayonne | |

| Coordinates: 40°39′45″N 74°06′37″W / 40.66253°N 74.110192°W[1][2] | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | |

| Incorporated | April 1, 1861 (as township) |

| Incorporated | March 10, 1869 (as city) |

| Named for | Bayonne, France, or location on two bays |

| Government | |

| • Type | Faulkner Act Mayor-Council |

| • Body | City Council |

| • Mayor | Jimmy M. Davis (term ends June 30, 2026)[3][4] |

| • Administrator | Donna Russo[5] |

| • Municipal clerk | Madelene C. Medina[6] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 11.22 sq mi (29.06 km2) |

| • Land | 5.82 sq mi (15.08 km2) |

| • Water | 5.40 sq mi (13.98 km2) 47.50% |

| • Rank | 201st of 565 in state 2nd of 12 in county[1] |

| Elevation | 7 ft (2 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 71,686 |

| • Estimate | 70,300 |

| • Rank | 543rd in country (as of 2022)[13] 15th of 565 in state 2nd of 12 in county[14] |

| • Density | 12,315.1/sq mi (4,754.9/km2) |

| • Rank | 24th of 565 in state 10th of 12 in county[14] |

| Time zone | UTC−05:00 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−04:00 (Eastern (EDT)) |

| ZIP Code | |

| Area codes | 201[17] |

| FIPS code | 3401703580[1][18][19] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0885151[1][20] |

| Website | www |

Bayonne (/beɪˈ(j)oʊn/ bay-(Y)OHN)[21][22][23][24][25] is a city in Hudson County in the U.S. state of New Jersey. Located in the Gateway Region, Bayonne is situated on a peninsula between Newark Bay to the west, the Kill Van Kull to the south, and New York Bay to the east. As of the 2020 United States census, the city was the state's 15th-most-populous municipality, surpassing 2010 #15 Passaic,[26] with a population of 71,686,[10][11] an increase of 8,662 (+13.7%) from the 2010 census count of 63,024,[27][28] which in turn reflected an increase of 1,182 (+1.9%) from the 61,842 counted in the 2000 census.[29] The Census Bureau's Population Estimates Program calculated that the city's population was 69,527 in 2022,[10] ranking the city the 543rd-most-populous in the country.[13]

Bayonne was originally formed as a township on April 1, 1861, from portions of Bergen Township. Bayonne was reincorporated as a city by an act of the New Jersey Legislature on March 10, 1869,[30] replacing Bayonne Township, subject to the results of a referendum held nine days later.[31] At the time it was formed, Bayonne included the communities of Bergen Point, Constable Hook, Centreville, Pamrapo and Saltersville.[32]

While somewhat diminished, traditional manufacturing, distribution, and maritime activities remain a driving force of the economy of the city. A portion of the Port of New York and New Jersey is located there, as is the Cape Liberty Cruise Port.

History

Originally inhabited by Native Americans, the region presently known as Bayonne was claimed by the Netherlands after Henry Hudson explored the Hudson River which is named after him.[33] According to Royden Page Whitcomb's 1904 book, First History of Bayonne, New Jersey, the name Bayonne is speculated to have originated with Bayonne, France, from which Huguenots settled for a year before the founding of New Amsterdam.[34] However, there is no empirical evidence for this notion. Whitcomb gives more credence to the idea that Erastus Randall, E.C. Bramhall and B.F. Woolsey, who bought the land owned by Jasper and William Cadmus for real estate speculation, named it Bayonne for purposes of real estate speculation, because it was located on the shores of two bays, Newark and New York.[35]

Bayonne became one of the largest centers in the nation for refining crude oil and Standard Oil of New Jersey's facility—which had grown from its original establishment in 1877—and its 6,000 employees made it the city's largest place of employment.[32] Significant civil unrest arose during the Bayonne refinery strikes of 1915–1916, in which mostly Polish-American workers staged labor actions against Standard Oil of New Jersey and Tidewater Petroleum, seeking improved pay and working conditions.[36] Four striking workers were killed when strikebreakers, allegedly protected by police, fired upon a violent crowd.[37]

The Cape Liberty Cruise Port is a cruise ship terminal that is on a 430-acre (170 ha) site that had been originally developed for industrial uses in the 1930s and then taken over by the U.S. government during World War II as the Military Ocean Terminal at Bayonne. Voyager of the Seas, departing from the cruise terminal in 2004, became the first passenger ship to depart from a port in New Jersey in almost 40 years.[38]

Geography and climate

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city had a total area of 11.09 square miles (28.72 km2), including 5.82 square miles (15.08 km2) of land and 5.27 square miles (13.64 km2) of water (47.50%).[1][2]

The city is located on a peninsula earlier known as Bergen Neck surrounded by Upper New York Bay to the east, Newark Bay to the west, and Kill Van Kull to the south.[32] Bayonne is east of Newark, the state's largest city, north of Elizabeth in Union County and west of Brooklyn. It shares a land border with Jersey City to the north and is connected to Staten Island by the Bayonne Bridge.[39][40][41]

Unincorporated communities, localities and place names located partially or completely within the city include:[42] Bergen Point, Constable Hook and Port Johnson.[citation needed]

Climate

Bayonne has a humid subtropical climate (Cfa) bordering a hot-summer humid continental climate (Dfa). The average monthly temperature varies from 32.3 °F in January to 77.0 °F in July.[43] The hardiness zone is 7b and the average absolute minimum temperature is 5.2 °F.[44]

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1870 | 3,834 | — | |

| 1880 | 9,372 | 144.4% | |

| 1890 | 19,033 | 103.1% | |

| 1900 | 32,722 | 71.9% | |

| 1910 | 55,545 | 69.7% | |

| 1920 | 76,754 | 38.2% | |

| 1930 | 88,979 | 15.9% | |

| 1940 | 79,198 | −11.0% | |

| 1950 | 77,203 | −2.5% | |

| 1960 | 74,215 | −3.9% | |

| 1970 | 72,743 | −2.0% | |

| 1980 | 65,047 | −10.6% | |

| 1990 | 61,444 | −5.5% | |

| 2000 | 61,842 | 0.6% | |

| 2010 | 63,024 | 1.9% | |

| 2020 | 71,686 | 13.7% | |

| 2023 (est.) | 70,300 | [10][13][12] | −1.9% |

| Population sources: 1870–1920[45] 1870[46][47] 1880–1890[48] 1890–1910[49] 1870–1930[50] 1940–2000[51] 2000[52][53] 2010[27][28] 2020[10][11] | |||

The city has an ethnically diverse population, home to large populations of Italian Americans, Irish Americans, Polish Americans, Indian Americans, Egyptian Americans, Dominican Americans, Mexican Americans, Salvadoran Americans, Pakistani Americans, Boricua, amongst others.[citation needed]

2010 census

The 2010 United States census counted 63,024 people, 25,237 households, and 16,051 families in the city. The population density was 10,858.3 per square mile (4,192.4/km2). There were 27,799 housing units at an average density of 4,789.4 per square mile (1,849.2/km2). The racial makeup was 69.21% (43,618) White, 8.86% (5,584) Black or African American, 0.31% (194) Native American, 7.71% (4,861) Asian, 0.03% (16) Pacific Islander, 10.00% (6,303) from other races, and 3.88% (2,448) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 25.79% (16,251) of the population.[27] Non-Hispanic Whites were 56.8% of the population.

Of the 25,237 households, 29.5% had children under the age of 18; 41.1% were married couples living together; 16.8% had a female householder with no husband present and 36.4% were non-families. Of all households, 31.6% were made up of individuals and 11.8% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.49 and the average family size was 3.16.[27]

22.5% of the population were under the age of 18, 8.9% from 18 to 24, 28.1% from 25 to 44, 27.3% from 45 to 64, and 13.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 38.4 years. For every 100 females, the population had 91.7 males. For every 100 females ages 18 and older there were 87.9 males.[27]

The U.S. Census Bureau's 2006–2010 American Community Survey showed that (in 2010 inflation-adjusted dollars) median household income was $53,587 (with a margin of error of +/− $2,278) and the median family income was $66,077 (+/− $5,235). Males had a median income of $51,188 (+/− $1,888) versus $42,097 (+/− $1,820) for females. The per capita income for the city was $28,698 (+/− $1,102). About 9.9% of families and 12.3% of the population were below the poverty line, including 20.5% of those under age 18 and 8.4% of those age 65 or over.[54]

2000 census

As of the 2000 United States census[18] there were 61,842 people, 25,545 households, and 16,016 families residing in the city. The population density was 10,992.2 inhabitants per square mile (4,244.1/km2). There were 26,826 housing units at an average density of 4,768.2 per square mile (1,841.0/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 78.8% White, 5.50% African American, 0.2% Native American, 4.1% Asian, 0.05% Pacific Islander, 7.46% from other races, and 4.02% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 17.81% of the population.[52][53]

As of the 2000 Census, the most common reported ancestries of Bayonne residents were Italian (20.1%), Irish (18.8%) and Polish (17.9%).[52][53]

There were 25,545 households, out of which 28.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 42.8% were married couples living together, 15.1% had a female householder with no husband present, and 37.3% were non-families. 32.8% of all households were made up of individuals, and 15.0% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.42 and the average family size was 3.10.[52][53]

In the city the population was spread out, with 22.1% under the age of 18, 8.2% from 18 to 24, 30.7% from 25 to 44, 22.5% from 45 to 64, and 16.6% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 38 years. For every 100 females, there were 89.9 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 86.3 males.[52][53]

The median income for a household in the city was $41,566, and the median income for a family was $52,413. Males had a median income of $39,790 versus $33,747 for females. The per capita income for the city was $21,553. About 8.4% of families and 10.1% of the population were below the poverty line, including 11.9% of those under age 18 and 11.0% of those age 65 or over.[52][53]

Economy

Portions of the city are part of an Urban Enterprise Zone (UEZ), one of 32 zones covering 37 municipalities statewide. Bayonne was selected in 2002 as one of a group of three zones added to participate in the program.[55] In addition to other benefits to encourage employment and investment within the Zone, shoppers can take advantage of a reduced 3.3125% sales tax rate (half of the 6+5⁄8% rate charged statewide) at eligible merchants.[56] Established in September 2002, the city's Urban Enterprise Zone status expires in December 2023.[57] More than 200 businesses have registered to participate in the city's UEZ since it was first established.[58]

The Bayonne Town Center, located within the Broadway shopping district, includes retailers, eateries, consumer and small business banking centers. The Bayonne Medical Center is a for-profit hospital that anchors the northern end of the Town Center. It is the city's largest employer, with over 1,200 employees. A 2013 study showed that the hospital charged the highest rates in the United States.[59]

Bayonne Crossing on Route 440 in Bayonne, includes a Lowe's and Wal-Mart.[60]

On the site of the former Military Ocean Terminal, the Peninsula at Bayonne Harbor includes new housing and businesses. One of them, Cape Liberty Cruise Port is located at the end of the long peninsula with Royal Caribbean.[61] Also found is a memorial park for the Tear of Grief, a 100-foot-high (30 m), 175-short-ton (159 t) monument commemorating the September 11 terrorist attacks and the 1993 World Trade Center bombing.[62]

The firearms manufacturing company Henry Repeating Arms moved from Brooklyn to Bayonne in 2009.[63][64]

Parks and recreation

Hackensack RiverWalk begins at Collins Park in Bergen Point where the Kill Van Kull meets the Newark Bay. Also along the bay is 16th Street Park. A plaque unveiled on May 2, 2006, for the new Richard A. Rutowski Park, a wetlands preserve on the northwestern end of town that is part of the RiverWalk. It is located immediately north of the Stephen R. Gregg Hudson County Park.[65]

Hudson River Waterfront Walkway is part of a walkway that is intended to run the more than 18 miles (29 km) from the Bayonne Bridge to the George Washington Bridge.[66][67]

In August 2014, the Bayonne Hometown Fair, a popular tourist and community attraction that ceased in 2000, was revived by a local business owner and resident. The first revived Bayonne Hometown Fair took place from June 6–7, 2015.[68]

Government

Local government

The City of Bayonne has been governed within the Faulkner Act, formally known as the Optional Municipal Charter Law, under the Mayor-Council system of municipal government (Plan C), implemented based on the recommendations of a Charter Study Commission as of July 1, 1962,[69] before which it was governed by a Board of Commissioners under the Walsh Act. The city is one of 71 municipalities (of the 564) statewide that use this form of government.[70] The governing body is comprised of the Mayor and the five-member City Council, of which two seats are chosen at-large and three from wards, all of whom serve four-year terms of office on a concurrent basis and are chosen in balloting held as part of the May municipal election.[7][3][71][72]

As of July 2022[update], the Mayor of Bayonne is James M. "Jimmy" Davis, whose term of office ends June 30, 2026; Davis was first elected as mayor in a runoff election on June 10, 2014, against incumbent Mayor Mark Smith. Members of the Bayonne City Council are Loyad Booker (at-large), Neil Carroll III (1st Ward), Gary La Pelusa Sr. (3rd Ward), Juan M. Perez (at-large) and Jacqueline Weimmer (2nd Ward), all of whom are serving concurrent terms of office that end on June 30, 2026.[3][73][74][75]

In November 2018, the City Council appointed Neil Carroll III to fill the 1st Ward seat vacated by Tommy Cotter, who resigned to take a position as the city's DPW director; at age 27, Carroll became the youngest councilmember in city history.[76] In the November 2019 general election, Carroll was elected to serve the balance of the term of office.[77]

Federal, state, and county representation

Bayonne is in the 8th Congressional District[78] and is part of New Jersey's 31st state legislative district.[79][80][81]

Prior to the 2010 Census, Bayonne had been split between the 10th Congressional District and the 13th Congressional District, a change made by the New Jersey Redistricting Commission that took effect in January 2013, based on the results of the November 2012 general elections.[82] The split placed 33,218 residents living in the city's south and west in the 8th District, while 29,806 residents in the northeastern portion of the city were placed in the 10th District.[83][84]

For the 118th United States Congress, New Jersey's 8th congressional district is represented by Rob Menendez (D, Jersey City).[85][86] New Jersey is represented in the United States Senate by Democrats Cory Booker (Newark, term ends 2027)[87] and Bob Menendez (Englewood Cliffs, term ends 2025).[88][89] For the 2024-2025 session, the 31st legislative district of the New Jersey Legislature is represented in the State Senate by Angela V. McKnight (D, Jersey City) and in the General Assembly by Barbara McCann Stamato (D, Jersey City) and William Sampson (D, Bayonne).[90]

Hudson County is governed by a directly elected County Executive and by a Board of County Commissioners, which serves as the county's legislative body. As of 2024[update], Hudson County's County Executive is Craig Guy (D, Jersey City), whose term of office expires December 31, 2027.[91] Hudson County's Commissioners are:[92][93][94]

Kenneth Kopacz (D, District 1-- Bayonne and parts of Jersey City; 2026, Bayonne),[95][96] William O'Dea (D, District 2-- western parts of Jersey City; 2026, Jersey City),[97][98] Vice Chair Jerry Walker (D, District 3-- southeastern parts of Jersey City; 2026, Jersey City),[99][100] Yraida Aponte-Lipski (D, District 4-- northeastern parts of Jersey City; 2026, Jersey City),[101][102] Chair Anthony L. Romano Jr. (D, District 5-- Hoboken and adjoining parts of Jersey City; 2026, Hoboken),[103][104] Fanny J.Cedeno (D, District 6-- Union City; 2026, Union City),[105][106] Caridad Rodriguez (D, District 7-- West New York (part), Weehawken, Guttenberg; 2026, West New York),[107][108] Robert Baselice (D, District 8-- North Bergen, West New York (part), Seacaucus (part); 2026, North Bergen),[109][110] and Albert Cifelli (D, District 9-- East Newark, Harrison, Kearny, and Secaucus (part); 2026, Harrison).[111][112]

Hudson County's constitutional officers are: Clerk E. Junior Maldonado (D, Jersey City, 2027),[113][114] Sheriff Frank Schillari, (D, Jersey City, 2025)[115] Surrogate Tilo E. Rivas, (D, Jersey City, 2024)[116][117] and Register Jeffery Dublin (D, Jersey City, 2024).[118][117]

Politics

As of March 2011, there were a total of 32,747 registered voters in Bayonne, of which 17,087 (52.2%) were registered as Democrats, 2,709 (8.3%) were registered as Republicans and 12,928 (39.5%) were registered as Unaffiliated. There were 23 voters registered to other parties.[119]

In the 2012 presidential election, Democrat Barack Obama received 66.4% of the vote (13,467 cast), ahead of Republican Mitt Romney with 32.6% (6,605 votes), and other candidates with 1.0% (197 votes), among the 20,454 ballots cast by the city's 34,424 registered voters (185 ballots were spoiled), for a turnout of 59.4%.[120][121] In the 2008 presidential election, Democrat Barack Obama received 57.0% of the vote here (13,768 cast), ahead of Republican John McCain with 40.6% (9,796 votes) and other candidates with 1.2% (283 votes), among the 24,139 ballots cast by the town's 35,823 registered voters, for a turnout of 67.4%.[122] In the 2004 presidential election, Democrat John Kerry received 56.0% of the vote here (12,402 ballots cast), outpolling Republican George W. Bush with 42.2% (9,341 votes) and other candidates with 0.6% (184 votes), among the 22,135 ballots cast by the town's 32,129 registered voters, for a turnout percentage of 68.9.[123]

In the 2013 gubernatorial election, Republican Chris Christie received 49.3% of the vote (5,322 cast), ahead of Democrat Barbara Buono with 49.1% (5,297 votes), and other candidates with 1.6% (169 votes), among the 10,987 ballots cast by the city's 34,957 registered voters (199 ballots were spoiled), for a turnout of 31.4%.[124][125] In the 2009 gubernatorial election, Democrat Jon Corzine received 53.8% of the vote here (7,421 ballots cast), ahead of Republican Chris Christie with 38.7% (5,333 votes), Independent Chris Daggett with 4.8% (662 votes) and other candidates with 1.3% (183 votes), among the 13,781 ballots cast by the town's 32,588 registered voters, yielding a 42.3% turnout.[126]

Local services

Municipal Utilities Authority

The Bayonne Municipal Utilities Authority (BMUA) is the second agency to use wind power in New Jersey and has built the first wind turbine in the metropolitan area.[127][128][129][130][131] Construction of a single turbine tower was completed in January 2012.[132][133] It is the first wind turbine created by Leitwind to be installed in the United States.[134]

In December 2012, the autonomous agency entered into a water management agreement with the Bayonne Water Joint Venture (BWJV), a partnership between United Water and investment firm KKR.[135] The 40-year concession agreement is a public-private partnership between the city and the BWJV in which the private partners pay off the BMUA's $130 million debt and take over the operations, maintenance, and capital improvement of Bayonne's water and wastewater utilities in exchange for a regulated share of the revenue.[136][137][138] United Water is managing the operations for the partnership, while KKR is providing 90% of the funding.[139] A rate schedule was included in the agreement, and it contained an immediate 8.5% utility rate increase (the first rate increase since 2006),[135] followed by two years without increases, followed by annual increases estimated to range between 2.5%–4.5%.[137] This partnership was sought for several reasons, including the BMUA's debt, its shortage of skilled employees, and its lagging rate revenue from years without rate increases and reduced demand.[136][140] Part of this reduced demand stemmed from the closure of the Military Ocean Terminal at Bayonne,[140] and the fact that the subsequent plans to redevelop the site with housing fell short.[141] The BMUA's $130 million debt that was paid off by the BWJV represented over half of Bayonne's overall debt ($240 million) at the time,[137] and in March 2013, Moody's Investors Service upgraded the credit rating of Bayonne from 'negative' to 'stable', citing the water deal.[139]

Fire department

The city of Bayonne has around 161 full-time professional firefighters consisting of the city of Bayonne Fire Department (BFD), which was founded on September 3, 1906, and operates out of five fire stations located throughout the city. The Bayonne Fire Dept operates a fleet of five engines, one squad (rescue-pumper), three ladder trucks, a heavy rescue truck (which is also part of the Metro USAR Collapse Rescue Strike Team), a large 4,000 gallon foam tanker truck, a haz-mat truck, a multi-service unit, a fireboat, as well as spare apparatus. Each tour is commanded by a battalion chief.[142]

The department is part of the Metro USAR Strike Team, which consists of nine North Jersey fire departments and other emergency services divisions working to address major emergency rescue situations.[143]

Education

Public schools

The Bayonne School District serves students from pre-kindergarten through twelfth grade.[144] As of the 2020–21 school year, the district, comprised of 13 schools, had an enrollment of 10,059 students and 763.0 classroom teachers (on an FTE basis), for a student–teacher ratio of 13.2:1.[145] Schools in the district (with 2020–21 enrollment data from the National Center for Education Statistics[146]) are John M. Bailey School No. 12[147] (656 students; in grades PreK-8), Mary J. Donohoe No. 4[148] (459; PreK-8), Henry E. Harris No. 1[149] (637; PreK-8), Lincoln Community School No. 5[150] (433; PreK-8), Horace Mann No. 6[151] (641; PreK-8), Nicholas Oresko School No. 14[152] (444; PreK-8), Dr. Walter F. Robinson No. 3[153] (772; PreK-8), William Shemin Midtown Community School No. 8[154] (1,230; PreK-8), Phillip G. Vroom No. 2[155] (485; PreK-8), George Washington Community School No. 9[156] (677; PreK-8), Woodrow Wilson School No. 10[157] (747; PreK-8), Bayonne High School[158] (1,290; 9-12) and Bayonne Alternative High School[159] (141; 9-12).[160][161][162][163] Bayonne High School is the only public school in the state to have an on-campus ice rink for its hockey team.[164][165]

During the 1998–99 school year, Midtown Community School No. 8 was recognized with the National Blue Ribbon School Award of Excellence by the United States Department of Education.[166] During the 2008–2009 school year, Nicholas Oresko School No. 14 was recognized as a Blue Ribbon School award, and Washington Community School No. 9 was honored during the 2009–2010 school year.[167]

For the 2004–05 school year, Mary J. Donohoe No. 4 School was named a "Star School" by the New Jersey Department of Education, the highest honor that a New Jersey school can achieve.[168] It is the fourth school in Bayonne to receive this honor. The other three are Bayonne High School in 1995–96,[169] Midtown Community School in 1996–97[170] and P.S. #14 in the 1998–99 school year.[171]

Private schools

Private schools in Bayonne include All Saints Catholic Academy, for grades Pre-K–8, which operates under the supervision of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Newark[172] and was one of eight private schools recognized in 2017 as an Exemplary High Performing School by the National Blue Ribbon Schools Program of the United States Department of Education.[173] Marist High School, a co-ed Catholic high school, announced in January 2020 that it would close at the end of the 2019–2020 school year due to deficits that had risen to $1 million and enrollment that had declined by 50% since 2008.[174]

The Yeshiva Gedolah of Bayonne is a yeshiva high school / beis medrash / Kolel with 130 students.[175]

Holy Family Academy for girls in ninth through twelfth grades was closed at the end of the 2012–2013 school year in the wake of financial difficulties and declining enrollment, having lost the support of the Sisters of St. Joseph of Chestnut Hill, Philadelphia in 2008.[176]

Libraries and museums

The Bayonne Public Library,[177] one of New Jersey's original 36 Carnegie libraries,[178] the Bayonne Community Museum,[179] the Bayonne Firefighters Museum,[180] and the Joyce-Herbert VFW Post 226 Veterans Museum[181] provide educational events and programs.

Media and culture

Bayonne is located within the New York media market, with most of its daily papers available for sale or delivery. Local, county, and regional news is covered by the daily Jersey Journal. The Bayonne Community News is part of The Hudson Reporter group of local weeklies. Other weeklies, the River View Observer and El Especialito also cover local news.[182] Bayonne-based periodicals include the Bayonne Evening Star-Telegram (B.E.S.T.).

Bayonne's local culture is served by the Annual Outdoor Art Show, which was instituted in 2008, in which local artists display their works.[183]

In the 1983 novel Winter's Tale by Mark Helprin, which is set in a fantastical version of New York City and its surroundings, "The Bayonne Marsh" is the hidden, inaccessible home of the Marshmen, a race of fierce warriors.[citation needed]

Jackie Gleason, a former headliner at the Hi-Hat Club in Bayonne, was fascinated by the city and mentioned it often in the television series The Honeymooners.[184]

Films set in Bayonne include the 1991 film Mortal Thoughts, with Demi Moore and Bruce Willis, which was filmed near Horace Mann School and locations around Bayonne and Hoboken;[185] the 2000 drama Men of Honor, starring Robert De Niro and Cuba Gooding Jr.; the 2002 drama Hysterical Blindness; and the 2005 Tom Cruise science fiction film War of the Worlds, which opens at the Bayonne home of the lead character, and depicts the destruction of the Bayonne Bridge by aliens. Films shot in Bayonne include the 2001 film A Beautiful Mind, scenes of which were filmed at the Peninsula at Bayonne Harbor,[186] and the 2008 Mickey Rourke drama The Wrestler, which was partially filmed in the Color & Cuts Salon and the former Dolphin Gym, both of which are on Broadway in Bayonne.[187][188]

The November 16, 2010, episode of The Daily Show with Jon Stewart parodied former Alaska Governor Sarah Palin's reality television series, Sarah Palin's Alaska, in the form of a trailer for a fictional reality show called Jason Jones' Bayonne, New Jersey, whose portrayal of the city was characterized by prostitution, drugs, crime, pollution and a stereotypical Italian-American population.[189] Bayonne Mayor Mark Smith criticized the sketch, saying, "Jon Stewart's unfortunate and inaccurate depiction of Bayonne represents a lame attempt at humor at the expense of a rock solid, all-American community."[190] It is also referenced in the humorous song "The Rolling Mills of New Jersey" by John Roberts and Tony Barrand as the narrator's home town.[191]

The comic strip Piranha Club (originally "Ernie"), drawn by Bud Grace, is set in and around Bayonne.[192]

The ABC sci-fi comedy television series The Neighbors is about a family that moves from Bayonne into a fictional gated community, Hidden Hills, that is populated by aliens from another planet posing as humans.[193]

Religion

The Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Newark operates Catholic churches. Two in Bayonne, Blessed Miriam Teresa Demjanovich Church and St. John Paul II Church, were formed from consolidations,[194] in 2016, because the number of people attending Catholic churches declined.[195]

Demjanovich church is a merger of St. Andrew and St. Mary Star of the Sea churches, with the merged congregation keeping the two sites for worship. Reverend Alexander Santora in the Jersey Journal wrote that due to the efforts of the pastor, the Demjanovich merger "went off, however, without a hitch."[196]

Three other churches, Our Lady of the Assumption, Our Lady of Mt. Carmel, and St. Michael/St. Joseph, merged into John Paul II in 2016.[197] There were unsuccessful protests to keep Assumption open,[198] and the archdiocese committed to closing that church.[199]

Bayonne's Jewish community is served by Temple Beth Am (Reform), Temple Emanu-El (Conservative), Ohav Zedek (Orthodox), and Chabad (Orthodox).[citation needed]

Transportationedit

Roads and highwaysedit

As of May 2010[update], the city had a total of 76.55 miles (123.20 km) of roadways, of which 65.78 miles (105.86 km) were maintained by the city, 4.82 miles (7.76 km) are overseen by Hudson County, 4.04 miles (6.50 km) by the New Jersey Department of Transportation and 1.91 miles (3.07 km) are the responsibility of the New Jersey Turnpike Authority.[200]

The Bayonne Bridge stretches 1,775 feet (541 m), connecting south to Staten Island over the Kill Van Kull. Originally constructed in 1931, the bridge underwent a Navigation Clearance Project that was completed in 2017 at a cost of $1.7 billion, that raised the bridge deck from 151 feet (46 m) above the water to 215 feet (66 m), allowing larger and more heavily laden cargo ships to clear their way under the bridge.[201]

Several major roadways pass through the city.[202] The Newark Bay Extension (Interstate 78) of the New Jersey Turnpike eastbound travels to Jersey City and, via the Holland Tunnel, Manhattan. Westbound, the Newark Bay Bridge provides access to Newark, Newark Liberty International Airport and the rest of the turnpike (Interstate 95).[203]

Kennedy Boulevard (County Route 501) is a major thoroughfare along the west side of the city from the Bayonne Bridge north to Jersey City and North Hudson.[204]

Route 440 runs along the east side of Bayonne, and the West Side of Jersey City, partially following the path of the old Morris Canal route.[205] It connects to the Bayonne Bridge, I-78, and to Route 185 to Liberty State Park.

Public transportationedit

The Hudson-Bergen Light Rail has four stops in Bayonne, all originally from the former Central Railroad of New Jersey (CNJ). They are located at 45th Street, 34th Street, 22nd Street, all just east of Avenue E, and 8th Street (the southern terminal of the 8th Street-Hoboken Line) at Avenue C, which opened in January 2011.[206][207]

Bus transportation is provided on three main north–south streets of the city: Broadway, Kennedy Boulevard, and Avenue C, both by the state-operated NJ Transit and several private bus lines.[208] The Broadway line runs solely inside Bayonne city limits, while bus lines on Avenue C and Kennedy Boulevard run to various end points in Jersey City. The NJ Transit 120 runs between Avenue C in Bayonne and Battery Park in Downtown Manhattan during rush hours in peak direction while the 81 provides service to Jersey City.[209][210][211]

MTA Regional Bus Operations provides bus service between Bayonne and Staten Island on the S89 route, which connects the 34th Street light rail station and the Eltingville neighborhood on Staten Island with no other stops in Bayonne. It is the first interstate bus service operated by the New York City Transit Authority.[212]

For 114 years, the CNJ ran frequent service through the city. Trains ran north to the Central Railroad of New Jersey Terminal in Jersey City. Trains ran west to Elizabethport, Elizabeth and Cranford for points west and south. The implementation of the Aldene Connection in 1967 bypassed CNJ trains around Bayonne so that nearly all trains would either terminate at Newark Pennsylvania Station or at Hoboken Terminal.[213] By 1973, a lightly used shuttle between Bayonne and Cranford that operated 20 times per day was the final remnant of service on the line.[214] Until August 6, 1978, a shuttle service between Bayonne and Cranford retained the last leg of service with the CNJ trains.[215]

Points of interestedit

- The Bayonne Bridge is the fifth-longest steel arch bridge in the world. For the more than 45 years from its dedication in 1931 until the completion of the New River Gorge Bridge, the Bayonne Bridge was the world's longest such bridge.[216]

- Bergen Point

- Constable Hook is the site of two burials grounds known as the Constable Hook Cemetery,[217] numerous tank farms and the Bayonne Golf Club, situated at the city's highest point

- Shooters Island, closed to the general public, is a 35 acres (14 ha) island—of which 7.5 acres (3.0 ha) are in Bayonne—that is operated as a bird sanctuary by the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation.[218]

- To the Struggle Against World Terrorism is a 100-foot (30 m) high sculpture by Zurab Tsereteli located at the end of the former Military Ocean Terminal that was given to the United States as an official gift of the Russian government as a memorial to the victims of the September 11 terrorist attacks and the 1993 World Trade Center bombing.[219] Russian President Vladimir Putin attended a groundbreaking ceremony in September 2005[220] and the monument was dedicated on September 11, 2006, in a ceremony attended by former President Bill Clinton as the keynote speaker.[221]

National Registered Historic Places and museumsedit

See List of Registered Historic Places in Hudson County, New Jersey

- Bayonne Truck House No. 1, home to Bayonne Firefighters Museum

- Bayonne Trust Company, home to Bayonne Community Museum

- First Reformed Dutch Church of Bergen Neck, constructed in 1866.[222]

- Robbins Reef Light – Built to serve ships heading into New York Harbor, the current structure at the site dates to 1883, replacing an earlier lighthouse constructed in 1839.[223]

- St. Vincent de Paul R.C. Church, constructed 1927–1930.

- Hale-Whitney Mansion

Notable peopleedit

People who were born in, residents of, or otherwise closely associated with Bayonne include ((B) denotes that the person was born in the city):

- Marc Acito (born 1966), playwright, novelist and humorist (B)[224]

- Walker Lee Ashley (born 1960), linebacker who played seven seasons in the NFL, for the Minnesota Vikings and Kansas City Chiefs (B)[225]

- Herbert R. Axelrod (1927–2017), tropical fish expert who was sentenced to prison in a tax fraud case (B)[226]

- Louis Ayres (1874–1947), architect best known for designing the United States Memorial Chapel at the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery and Memorial and the Herbert C. Hoover U.S. Department of Commerce Building (B)[227]

- Alexander Barkan (1909–1990), head of the AFL–CIO's Committee on Political Education from 1963 until 1982, and an original member of Nixon's Enemies List (B)[228]

- Allan Benny (1867–1942), Bayonne council member who later represented New Jersey's 9th congressional district from 1903 to 1905[229]

- Ben Bernie (1891–1943), bandleader, author, violinist, composer and conductor who wrote Sweet Georgia Brown (B)[230]

- Tammy Blanchard (born 1976), actress who won an Emmy Award for her portrayal of Judy Garland in Life with Judy Garland: Me and My Shadows[231]

- Marcy Borders (1973–2015), bank clerk who was known as "the dust lady" for an iconic photo taken of her after she survived the collapse of the World Trade Center[232]

- Joe Borowski (born 1971), professional baseball player for the Cleveland Indians[233]

- Kenny Britt (born 1988), wide receiver for the New England Patriots (B)[234][235]

- Dick Brodowski (1932–2019), Major League Baseball pitcher, who came up with the Boston Red Sox as a 19-year-old[236]

- Clem Burke (born 1955), drummer who was an original member of the band Blondie (B)[237]

- Scott Byers (born 1958), former American football defensive back who played in the NFL for the San Diego Chargers (B)[238]

- Walter Chandoha (1920–2019), animal photographer, known especially for his 90,000 photographs of cats (B)[239]

- Leon Charney (1938–2016), real estate tycoon, author, philanthropist, political pundit and media personality (B)[240]

- Cy Chermak (1929–2021), producer and screenwriter, notable for producing the crime drama television series CHiPs and Ironside (B)[241]

- Anthony Chiappone (born 1957), indicted politician who served in the New Jersey General Assembly, where he represented the 31st Legislative District from 2004 to 2005 and again from 2007[242] until his resignation in 2010.[243]

- Richard Halsey Best (1910–2001), dive bomber pilot and squadron commander in the United States Navy during World War II (B)[244]

- Robert Coello (born 1984), MLB pitcher who has played for the Boston Red Sox, Toronto Blue Jays and the Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim[245]

- Robert B. Cohen (1925–2012), founder of the Hudson News chain of newsstands that began in 1987 with a single location at LaGuardia Airport (B)[246]

- Dennis P. Collins (1924–2009), former Mayor of Bayonne who served four terms in office, from 1974 to 1990[247]

- George Cummings (born 1938), guitarist for the 1970s pop band, Dr. Hook & The Medicine Show[248]

- Bert Daly (1881–1952), physician and MLB infielder for the Philadelphia Athletics who served five terms as mayor of Bayonne (B)[249]

- Tom De Haven (born 1949), author, editor and journalist (B)[250]

- Sandra Dee (1942–2005), actress best known for her role as Gidget (B)[251]

- Teresa Demjanovich (1901–1927), Ruthenian Catholic Sister of Charity, who has been beatified by the Catholic Church (B)[252]

- Martin Dempsey (born 1952), retired United States Army general who served as the 18th chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff from October 1, 2011, until September 25, 2015[253]

- Rich Dimler (born 1956), former nose tackle for the Cleveland Browns and Green Bay Packers (B)[254]

- James P. Dugan (1929–2021), former member of the New Jersey Senate who served as chairman of the New Jersey Democratic State Committee (B)[255]

- William Abner Eddy (1850–1909), accountant and journalist famous for his photographic and meteorological experiments with kites.[256]

- Michael Farber (born 1951), author and sports journalist, who was a writer with Sports Illustrated from 1994 to 2014[257]

- Barney Frank (born 1940), member of the United States House of Representatives from Massachusetts from 1981 until 2013 (B)[258]

- Rich Glover (born 1950) former professional football player, who played defensive tackle in the NFL for the New York Giants and Philadelphia Eagles (B)[259]

- Joshua Gomez (born 1975), actor best known for his role as Morgan Grimes on Chuck (B)[260]

- Rick Gomez (born 1972), actor who portrayed Sgt. George Luz, in the HBO television miniseries Band of Brothers[261]

- Arielle Holmes (born 1993), actress and writer best known for starring as a lightly fictionalized version of herself in the film Heaven Knows What[262]

- Danan Hughes (born 1970), former football wide receiver who played in the NFL for the Kansas City Chiefs (B)[263]

- Nathan L. Jacobs (1905–1989), Justice of the New Jersey Supreme Court in 1948 and from 1952 to 1975[264]

- Herman Kahn (1922–1983), military strategist[265][266]

- Brian Keith (1921–1997), film and TV actor who appeared in The Russians Are Coming, the Russians Are Coming and as Uncle Bill in Family Affair (B)[267]

- Frank Langella (born 1940), actor who has appeared in over 70 productions including Dave and Good Night, and Good Luck. (B)[268]

- Bob Latour (1925–2010), swimming coach who organized and served as the first coach of the men's swimming team at Bucknell University from 1956 to 1968 (B)[269]

- Joseph A. LeFante (1928–1977), politician who represented New Jersey's 14th congressional district from 1977 to 1978 (B)[270]

- Jammal Lord (born 1981), former safety for the Houston Texans[271]

- Donald MacAdie (1899–1963), Suffragan Bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Newark from 1958 to 1963[272]

- George R. R. Martin (born 1948), author and screenwriter of science fiction, horror, and fantasy (B)[273]

- Pat Colasurdo Mayo (born 1957), former basketball player who played professionally for the San Francisco Pioneers in the Women's Professional Basketball League[274]

- Benjamin Melniker (1913–2018), film producer who was an executive producer with Michael E. Uslan on the Batman film series (B)[275]

- Miriam Moskowitz (1916–2018), schoolteacher who served two years in prison after being convicted for conspiracy as an atomic spy for the Soviet Union[276]

- Devora Nadworney (1895–1948), contralto singer who, in 1928, became the first singer heard over a radio network in the United States[277]

- Francis M. Nevins (born 1943), mystery writer, attorney, and professor of law (B)[278]

- Samuel Irving Newhouse Sr. (1895–1979), publishing and broadcasting executive who founded Advance Publications[279]

- Jim Norton (born 1968), standup comedian known for The Opie & Anthony Show, the Jim Norton & Sam Roberts show and The Tonight Show with Jay Leno[280]

- Denise O'Connor (born 1935), fencer who competed for the United States in the women's team foil events at the 1964 and 1976 Summer Olympics (B)[281]

- Jason O'Donnell (born 1971), member of the New Jersey General Assembly who represented the 31st Legislative District from 2010 to 2016[282]

- Gene Olaff (1920–2017), early professional soccer goalie (B)[283]

- Peter George Olenchuk (1922–2000), United States Army Major General[284]

- Shaquille O'Neal (born 1972), all-star basketball player for various NBA teams[285]

- Nicholas Oresko (1917–2013), United States Army Master Sergeant and recipient of the Medal of Honor (B)[286]

- Ronald Roberts (born 1991), professional basketball player who played for Hapoel Jerusalem of the Israeli Premier League[287]

- Steven V. Roberts (born 1943), journalist, writer and political commentator[288]

- William Sampson (born 1989), politician who has represented the 31st Legislative District in the New Jersey General Assembly since 2022 (B)[289]

- Dick Savitt (1927–2023), tennis player who reached a ranking of second in the world (B)[290][291]

- William Shemin (1896–1973), U.S. Army sergeant, Medal of Honor recipient and namesake of the William Shemin Midtown Community School (B)[292]

- William N. Stape (born 1968), screenwriter and magazine writer who wrote episodes of Star Trek: The Next Generation and Star Trek: Deep Space Nine[293]

- Corey Stokes (born 1988), college basketball player for Villanova University (B)[294]

- Robert Tepper (born 1953), singer/songwriter best known for the song "No Easy Way Out" from the Rocky IV motion picture soundtrack (B)[295]

- Joseph W. Tumulty (1914–1996), attorney and politician who represented the 32nd Legislative District for a single four-year term in the New Jersey Senate[296]

- James Urbaniak (born 1963), film and TV actor best known for his role as the voice of Dr. Thaddeus Venture in The Venture Bros. (B)[297]

- Michael E. Uslan (born 1951), originator and executive producer of the Batman/Dark Knight/Joker movie franchise[298]

- Chuck Wepner (born 1939), hard-luck boxer who was known as "The Bayonne Bleeder"[299]

- George Wiley (1931–1973), chemist and civil rights leader (B)[300]

- Zakk Wylde (born 1967), hard rock and heavy metal guitarist (B)[301]

Referencesedit

- ^ a b c d e 2019 Census Gazetteer Files: New Jersey Places Archived March 21, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, United States Census Bureau. Accessed July 1, 2020.

- ^ a b US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990 Archived August 24, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, United States Census Bureau. Accessed September 4, 2014.

- ^ a b c Mayor Jimmy Davis Archived October 7, 2022, at the Wayback Machine, City of Bayonne. Accessed November 30, 2022.

- ^ 2023 New Jersey Mayors Directory Archived March 11, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Department of Community Affairs, updated February 8, 2023. Accessed February 10, 2023.

- ^ Division of Administration Archived April 11, 2022, at the Wayback Machine, City of Bayonne. Accessed April 10, 2022.

- ^ City Clerk Archived October 2, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, City of Bayonne. Accessed May 13, 2024.

- ^ a b 2012 New Jersey Legislative District Data Book, Rutgers University Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy, March 2013, p. 135.

- ^ "ArcGIS REST Services Directory". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on January 19, 2022. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- ^ "City of Bayonne". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved March 4, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f QuickFacts Bayonne city, New Jersey Archived October 2, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, United States Census Bureau. Accessed January 9, 2023.

- ^ a b c Total Population: Census 2010 - Census 2020 New Jersey Municipalities Archived February 13, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development. Accessed December 1, 2022.

- ^ a b Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Minor Civil Divisions in New Jersey: April 1, 2020 to July 1, 2023, United States Census Bureau, released May 2024. Accessed May 16, 2024.

- ^ a b c Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places of 50,000 or More, Ranked by July 1, 2022 Population: April 1, 2020 to July 1, 2022 Archived July 17, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, United States Census Bureau, released May 2023. Accessed May 18, 2023. Note that townships (including Edison, Lakewood and Woodbridge, all of which have larger populations) are excluded from these rankings.

- ^ a b Population Density by County and Municipality: New Jersey, 2020 and 2021 Archived March 7, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development. Accessed March 1, 2023.

- ^ Look Up a ZIP Code for Bayonne, NJ Archived May 31, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, United States Postal Service. Accessed November 27, 2011.

- ^ ZIP Codes Archived June 17, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, State of New Jersey. Accessed August 25, 2013.

- ^ Area Code Lookup - NPA NXX for Bayonne, NJ Archived May 8, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, Area-Codes.com. Accessed October 29, 2013.

- ^ a b U.S. Census website Archived December 27, 1996, at the Wayback Machine, United States Census Bureau. Accessed September 4, 2014.

- ^ Geographic Codes Lookup for New Jersey Archived November 19, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, Missouri Census Data Center. Accessed April 1, 2022.

- ^ US Board on Geographic Names Archived February 12, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, United States Geological Survey. Accessed September 4, 2014.

- ^ Wright, E. Assata. "Secaucus: How do you pronounce it? Development put town on map, but newcomers don't know where they are" Archived November 30, 2022, at the Wayback Machine, The Hudson Reporter, July 6, 2011. Accessed November 30, 2022. "Therefore, the new neighbors may proudly totter about telling folks they live in Sih-KAW-cus or See-KAW-cus. However, natives prefer that the accent be on the first syllable, as in: SEE-kaw-cus.... Bayonne is bay-OWN, not ba-YON, locals say."

- ^ Lefferts, Walter. Our Own United States Archived October 2, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, p. 333. J. B. Lippincott & Co., 1925. Accessed November 15, 2020. "Bayonne. Bay-own'"

- ^ Holt, Alfred Hubbard. American Place Names Archived October 2, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, p. 26. Gale, 1969. Accessed November 15, 2020. "Bayonne, N . J . 'Bay - own.' Long a, long o; slightly more accent on the 'own'."

- ^ "Bayonne". Lexico US English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on May 11, 2022.

- ^ "Bayonne". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary.

- ^ Table1. New Jersey Counties and Most Populous Cities and Townships: 2020 and 2010 Censuses Archived February 13, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development. Accessed December 1, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e DP-1 - Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 for Bayonne city, Hudson County, New Jersey, United States Census Bureau. Accessed February 9, 2012.

- ^ a b Table DP-1. Profile of General Demographic Characteristics: 2010 for Bayonne city Archived May 6, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development. Accessed February 9, 2012.

- ^ Table 7. Population for the Counties and Municipalities in New Jersey: 1990, 2000 and 2010 Archived June 2, 2022, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development, February 2011. Accessed May 1, 2023.

- ^ Charter of City of Bayonne Archived April 25, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Bayonne Historical Society. Accessed November 28, 2011.

- ^ Snyder, John P. The Story of New Jersey's Civil Boundaries: 1606-1968 Archived December 2, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, Bureau of Geology and Topography; Trenton, New Jersey; 1969. p. 146. Accessed February 9, 2012.

- ^ a b c History Archived May 10, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, City of Bayonne. Accessed November 12, 2019. "In 1877, the standard Oil Company took over a small refinery. By the 1920s, Standard Oil became the city's largest employer with over 6,000 workers. At that time, Bayonne was one of the largest oil refinery centers in the world."

- ^ Griffin, Molly. "Bayonne Historical Society learns about the Lenape" Archived November 12, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, NJ Advance Media for NJ.com, February 12, 2009, updated February 12, 2019. Accessed November 12, 2019. "Dr. Oeistreicher is a leading authority on the Lenape Indians, a tribe Hudson encountered when he explored what is now known as the Hudson River."

- ^ Hutchinson, Viola L. The Origin of New Jersey Place Names Archived November 15, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Public Library Commission, May 1945. Accessed August 27, 2015.

- ^ Whitcomb, Royden Page. First history of Bayonne, New Jersey, R.P. Whitcomb, Bayonne, New Jersey, 1904, Page 61, Google Books. Accessed November 20, 2010.

- ^ Dorsey, George. "The Bayonne Refinery Strikes of 1915-1916" Archived January 12, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Polish American Studies, Vol. 33, No. 2 (Autumn, 1976), pp. 19-30, Polish American Historical Association. Accessed June 13, 2012.

- ^ Brenner, Aaron; Day, Benjamin; and Ness, Emmanuel. The Encyclopedia of Strikes in American History Archived October 2, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, M. E. Sharpe, 2009. ISBN 0765613301. Accessed June 13, 2012.

- ^ History Archived November 22, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, Cape Liberty Cruise Port. Accessed November 12, 2019. "The 430 acre site in Lower New York Harbor was created by private developers in the 1930s as a man-made peninsula off the eastern end of Bayonne, New Jersey. Initially developed for industrial use, the U.S. War Department and the Department of the Navy became interested in the site as World War II approached.... The maiden sailing of the Voyager of the Seas was on May 14, 2004. The voyage marked the first time a passenger ship vessel had sailed from New Jersey in almost 40 years."

- ^ Areas touching Bayonne Archived March 19, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, MapIt. Accessed March 18, 2020.

- ^ Hudson County Map Archived April 30, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, Coalition for a Healthy NJ. Accessed March 18, 2020.

- ^ New Jersey Municipal Boundaries Archived December 4, 2003, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Department of Transportation. Accessed November 15, 2019.

- ^ Locality Search Archived July 9, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, State of New Jersey. Accessed May 22, 2015.

- ^ Time Series Values for Individual Locations Archived July 25, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, PRISM Climate Group. Accessed March 18, 2020.

- ^ Plant Hardiness Interactive Map Archived July 4, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, United States Department of Agriculture. Accessed March 18, 2020.

- ^ Compendium of censuses 1726-1905: together with the tabulated returns of 1905 Archived February 26, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Department of State, 1906. Accessed July 30, 2013.

- ^ Raum, John O. The History of New Jersey: From Its Earliest Settlement to the Present Time, Volume 1, p. 264, J. E. Potter and company, 1877. Accessed July 30, 2013. "Bayonne City contains a population of 3,834."

- ^ Staff. A compendium of the ninth census, 1870, p. 259. United States Census Bureau, 1872. Accessed July 30, 2013.

- ^ Porter, Robert Percival. Preliminary Results as Contained in the Eleventh Census Bulletins: Volume III - 51 to 75 Archived October 1, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, p. 98. United States Census Bureau, 1890. Accessed July 30, 2013.

- ^ Thirteenth Census of the United States, 1910: Population by Counties and Minor Civil Divisions, 1910, 1900, 1890, United States Census Bureau, p. 337. Accessed November 11, 2012.

- ^ Fifteenth Census of the United States : 1930 - Population Volume I Archived September 30, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, United States Census Bureau. Accessed February 8, 2012.

- ^ Table 6: New Jersey Resident Population by Municipality: 1940 - 2000 Archived October 5, 2022, at the Wayback Machine, Workforce New Jersey Public Information Network, August 2001. Accessed May 1, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Census 2000 Profiles of Demographic / Social / Economic / Housing Characteristics for Bayonne city, New Jersey Archived January 12, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, United States Census Bureau. Accessed July 7, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f DP-1: Profile of General Demographic Characteristics: 2000 - Census 2000 Summary File 1 (SF 1) 100-Percent Data for Bayonne city, Hudson County, New Jersey, United States Census Bureau. Accessed July 7, 2013.

- ^ DP03: Selected Economic Characteristics from the 2006-2010 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates for Bayonne city, Hudson County, New Jersey, United States Census Bureau. Accessed February 8, 2012.

- ^ Urban Enterprise Zone Tax Questions and Answers Archived January 12, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Department of Community Affairs, May 2009. Accessed October 28, 2019. "The legislation was amended again in 2002 to include 3 more zones. They include Bayonne City, Roselle Borough, and a joint zone consisting of North Wildwood City, Wildwood City, Wildwood Crest Borough, and West Wildwood Borough."

- ^ Urban Enterprise Zone Program Archived July 21, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Department of Community Affairs. Accessed October 27, 2019. "Businesses participating in the UEZ Program can charge half the standard sales tax rate on certain purchases, currently 3.3125% effective 1/1/2018"

- ^ Urban Enterprise Zone Effective and Expiration Dates Archived September 23, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Department of Community Affairs. Accessed January 8, 2018.

- ^ Bayonne Urban Enterprise Zone (UEZ) Archived November 3, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, City of Bayonne. Accessed November 19, 2019. "Bayonne is one of the State's newest Urban Enterprise Zones, and was first designated on September 12, 2002.Since its inception, over 213 businesses have registered in the Bayonne Urban Enterprise Zone program."

- ^ Livio, Susan K.; and Goldberg, Dan. "Bayonne Medical Center is at the top of hospital price list in nation" Archived September 22, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, The Star-Ledger, May 17, 2013. Accessed August 6, 2013. "Bayonne Medical Center, a 278-bed for-profit hospital in working-class Hudson County, charges the highest prices of any hospital in the nation, according to an analysis of federal billing data released by the Obama administration."

- ^ Sullivan, Al. "Good news for Bayonne commercial development; New stores, health facilities; shopping areas see promotions" Archived November 23, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. The Hudson Reporter. May 10, 2010. Accessed December 30, 2014.

- ^ "Cape Liberty Cruise Port". Archived from the original on May 30, 2023. Retrieved October 13, 2010.

- ^ The Memorial at Harbor View Park Archived December 31, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, 9/11 Monument. Accessed December 30, 2014. "Bayonne was a fitting location; the city was an arrival point for many New York City evacuees on 9/11, a staging area for rescuers and offered a direct view of the Statue of Liberty and the former World Trade Center towers."

- ^ About Us Archived February 14, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Henry Repeating Arms. Accessed December 6, 2011. "Today, the Henry Repeating Arms Company, a descendant of the venerable gunmaker, makes its home in Bayonne, New Jersey."

- ^ McGeehan, Patrick. "Soft Real Estate Market Is a Key Ingredient at Brooklyn Brewery" Archived January 26, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, November 1, 2009. Accessed December 6, 2011. "Still, other small manufacturers, like Henry Repeating Arms, have been leaving the city in search of less expensive places to operate.... They no longer are. Mr. Imperato, who lives in Bay Ridge, moved his company to Bayonne, N.J., last year after searching for a few years for adequate space to buy at a 'reasonable' price, he said. With some financial help from the State of New Jersey, the company bought a building on three acres in Bayonne for one-third of what it would have cost in Brooklyn, he said."

- ^ Kaulessar, Ricardo. "The other waterfront walkway: 18-mile Hackensack RiverWalk in Hudson County still underdeveloped" Archived December 18, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, The Hudson Reporter, May 16, 2006. Accessed December 6, 2011. "While the Bayonne and Secaucus portions of the Hackensack RiverWalk have been developed substantially, the Jersey City portion that would make up the majority of the 18-mile walk is far from reality. Anyone who develops along this stretch of the Hackensack River is required to add to the public RiverWalk, a planned linkage of waterfront parks along the Hackensack.... The RiverWalk section in Bayonne, if fully completed, would run from the southwest corner of the town in an area where the Kill Van Kull meets the Newark Bay, to the northwestern point of the area.... Ryan pointed out last week that another piece of the RiverWalk will be unveiled when the North 40 Park, or Richard A. Rutkowski Park, is scheduled to open this week."

- ^ Coastal Management Program Archived February 29, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection. Accessed December 6, 2011. "When complete, this Walkway will be an urban waterfront corridor connecting the George Washington Bridge in Fort Lee with the Bayonne Bridge in Bayonne. As the crow flies it will extend about 18.4 miles, but the total length will exceed 40 miles."

- ^ Walkway Map Archived August 15, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, Hudson River Waterfront Walkway. Accessed August 23, 2015. "The walkway covers 18.5 linear miles from Bayonne to the George Washington Bridge."

- ^ McGovern, Patrick. "Bayonne's Hometown Fair returns!" Archived January 13, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, The Jersey Journal, June 8, 2015. Accessed August 27, 2015.

- ^ "The Faulkner Act: New Jersey's Optional Municipal Charter Law" Archived October 12, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey State League of Municipalities, July 2007. Accessed October 29, 2013.

- ^ Inventory of Municipal Forms of Government in New Jersey Archived June 1, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, Rutgers University Center for Government Studies, July 1, 2011. Accessed June 1, 2023.

- ^ "Forms of Municipal Government in New Jersey" Archived June 4, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, p. 10. Rutgers University Center for Government Studies. Accessed June 1, 2023.

- ^ Broadway National Bank of Bayonne v. Parking Authority Archived April 22, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Superior Court, Law Division decided August 2, 1962. Via FindACase.com. Accessed November 27, 2011. "The facts are undisputed. The City of Bayonne was governed by a board of commissioners in accordance with the Walsh Act until July 1, 1962.... Mayor-Council Plan C of the Faulkner Act (NJSA 40:69A-1 et seq.) was adopted by referendum in the City of Bayonne and took effect on July 1, 1962."

- ^ 2022 Municipal Data Sheet Archived December 1, 2022, at the Wayback Machine, City of Bayonne. Accessed November 30, 2022.

- ^ 2022 Municipal Election May 10, 2022 Official Results Archived September 27, 2022, at the Wayback Machine, Hudson County, New Jersey, updated June 1, 2022. Accessed November 28, 2022.

- ^ Elected Officials Archived November 12, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, Hudson County, New Jersey Clerk. Accessed November 28, 2022.

- ^ Heinis, John. "As expected, Bayonne council appoints Carroll III to replace Cotter in the 1st Ward" Archived November 12, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, Hudson County View, November 20, 2018. Accessed November 12, 2019. "As expected, the Bayonne City Council voted to appoint Neil Carroll III to replace Tommy Cotter as the 1st Ward councilman at a brief special meeting this evening.... He beat out more than a dozen other candidates and Cotter has moved on to the director of the Department of Public Works for a salary of $117,000 a year. At just 27 years old, Carroll is the youngest councilman in Bayonne history. When asked about the criticism of being too young to handle the job, he said that his situation is not completely unprecedented."

- ^ Hudson County General Election 2018 Statement of Vote November 5, 2019 Archived January 7, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, Hudson County, New Jersey Clerk, updated November 13, 2019. Accessed January 1, 2020.

- ^ 2022 Redistricting Plan Archived October 28, 2022, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Redistricting Commission, December 8, 2022.

- ^ Municipalities Sorted by 2011-2020 Legislative District Archived November 20, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Department of State. Accessed February 1, 2020.

- ^ 2019 New Jersey Citizen's Guide to Government Archived November 5, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey League of Women Voters. Accessed October 30, 2019.

- ^ Districts by Number for 2011-2020 Archived July 14, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Legislature. Accessed January 6, 2013.

- ^ 2011 New Jersey Citizen's Guide to Government Archived June 4, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, p. 54, New Jersey League of Women Voters. Accessed May 22, 2015.

- ^ Plan Components Report Archived February 19, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Redistricting Commission, December 23, 2011. Accessed February 1, 2020.

- ^ New Jersey Congressional Districts 2012-2021: Bayonne Map Archived February 19, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Department of State. Accessed February 1, 2020.

- ^ Directory of Representatives: New Jersey, United States House of Representatives. Accessed January 3, 2019.

- ^ Biography, Congressman Albio Sires. Accessed January 3, 2019. "Congressman Sires resides in West New York with his wife, Adrienne."

- ^ U.S. Sen. Cory Booker cruises past Republican challenger Rik Mehta in New Jersey, PhillyVoice. Accessed April 30, 2021. "He now owns a home and lives in Newark's Central Ward community."

- ^ Biography of Bob Menendez, United States Senate, January 26, 2015. "Menendez, who started his political career in Union City, moved in September from Paramus to one of Harrison's new apartment buildings near the town's PATH station.."

- ^ Home, sweet home: Bob Menendez back in Hudson County. nj.com. Accessed April 30, 2021. "Booker, Cory A. - (D - NJ) Class II; Menendez, Robert - (D - NJ) Class I"

- ^ Legislative Roster for District 31, New Jersey Legislature. Accessed January 20, 2024.

- ^ Thomas A. DeGise, Hudson County Executive, Hudson County, New Jersey. Accessed August 17, 2017.

- ^ Message From The Chair, Hudson County, New Jersey. Accessed August 17, 2017.

- ^ County Officials, Hudson County, New Jersey. Accessed August 17, 2017.

- ^ 2017 County Data Sheet, Hudson County, New Jersey. Accessed August 17, 2017.

- ^ Freeholder District 1, Hudson County, New Jersey. Accessed August 17, 2017.

- ^ Kenneth Kopacz, Hudson County, New Jersey. Accessed August 17, 2017.

- ^ Freeholder District 2, Hudson County, New Jersey. Accessed August 17, 2017.

- ^ William O'Dea, Hudson County, New Jersey. Accessed August 17, 2017.

- ^ Freeholder District 3, Hudson County, New Jersey. Accessed August 17, 2017.

- ^ Gerard M. Balmir Jr., Hudson County, New Jersey. Accessed August 17, 2017.

- ^ Freeholder District 4, Hudson County, New Jersey. Accessed August 17, 2017.

- ^ E. Junior Maldonado, Hudson County, New Jersey. Accessed August 17, 2017.

- ^ Freeholder District 5, Hudson County, New Jersey. Accessed August 17, 2017.

- ^ Anthony L. Romano, Jr., Hudson County, New Jersey. Accessed August 17, 2017.

- ^ Freeholder District 6, Hudson County, New Jersey. Accessed August 17, 2017.

- ^ Tilo Rivas, Hudson County, New Jersey. Accessed August 17, 2017.

- ^ Freeholder District 7, Hudson County, New Jersey. Accessed August 17, 2017.

- ^ Caridad Rodriguez, Hudson County, New Jersey. Accessed August 17, 2017.

- ^ Freeholder District 8, Hudson County, New Jersey. Accessed August 17, 2017.

- ^ Anthony P. Vainieri Jr., Hudson County, New Jersey. Accessed August 17, 2017.

- ^ Freeholder District 9, Hudson County, New Jersey. Accessed August 17, 2017.

- ^ Albert J. Cifelli, Hudson County, New Jersey. Accessed August 17, 2017.

- ^ E. Junior Maldonado Archived September 2, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, Hudson County Clerk. Accessed January 30, 2018.

- ^ Members List: Clerks Archived October 23, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, Constitutional Officers Association of New Jersey. Accessed January 30, 2018.

- ^ Home page, Hudson County Sheriff's Office. Accessed August 17, 2017.

- ^ Hudson County Surrogate, Hudson County, New Jersey. Accessed March 26, 2021.

- ^ a b "Surrogates | COANJ". Retrieved March 26, 2021.

- ^ 1, Hudson County, New Jersey. Accessed March 26, 2021.

- ^ Voter Registration Summary - Hudson Archived May 20, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Department of State Division of Elections, March 23, 2011. Accessed November 13, 2012.

- ^ "Presidential General Election Results - November 6, 2012 - Hudson County" (PDF). New Jersey Department of Elections. March 15, 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 26, 2014. Retrieved December 24, 2014.

- ^ "Number of Registered Voters and Ballots Cast - November 6, 2012 - General Election Results - Hudson County" (PDF). New Jersey Department of Elections. March 15, 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 26, 2014. Retrieved December 24, 2014.

- ^ 2008 Presidential General Election Results: Hudson County Archived May 20, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Department of State Division of Elections, December 23, 2008. Accessed November 13, 2012.

- ^ 2004 Presidential Election: Hudson County Archived May 20, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Department of State Division of Elections, December 13, 2004. Accessed November 13, 2012.

- ^ "Governor - Hudson County" (PDF). New Jersey Department of Elections. January 29, 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved December 24, 2014.

- ^ "Number of Registered Voters and Ballots Cast - November 5, 2013 - General Election Results - Hudson County" (PDF). New Jersey Department of Elections. January 29, 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved December 24, 2014.

- ^ 2009 Governor: Hudson County, New Jersey Department of State Division of Elections, December 31, 2009. Accessed November 13, 2012.

- ^ Hack, Charles. "Bayonne MUA says windmill will start generating electricity next year" Archived June 24, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, The Jersey Journal, August 12, 2011. Accessed August 29, 2015.

- ^ Staff. "Uncle Sam paying most of Bayonne's windmill tab" Archived July 28, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, The Jersey Journal/NJ.com, June 18, 2009. Accessed August 29, 2015.

- ^ Staff. "Wind turbine to save Bayonne big bucks in long run" Archived November 29, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. The Jersey Journal/NJ.com, August 23, 2010. Accessed August 29, 2015.

- ^ Sullivan, Al. "All geared up: Windmill construction would power MUA" Archived January 13, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. The Hudson Reporter, December 21, 2011. Accessed August 29, 2015.

- ^ Hack, Charles. "Work on Bayonne windmill to resume shortly" Archived July 14, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. The Jersey Journal/NJ.com, May 8, 2011. Accessed August 29, 2015.

- ^ Kowsh, Kate. "Bayonne Municipal Utilities Authority's towering wind-turbine project takes form as crane lifts center piece into place" Archived January 22, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, The Jersey Journal, January 19, 2012. Accessed August 29, 2015.

- ^ Kowsh, Kate. "Bayonne completes construction of wind-turbine project" Archived January 25, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, The Jersey Journal, January 20, 2012. Accessed August 29, 2015.

- ^ "Leitwind goes to America: The first wind turbine for the USA to be delivered by year's end", Leitwind. Accessed February 9, 2012.

- ^ a b Hack, Charles (July 23, 2012). "United Water to take over operations of Bayonne's water, sewer systems in $150 million deal" Archived July 27, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. NJ.com

- ^ a b "Bayonne Revisited: Water Partnerships One Year Later" Archived October 18, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, Sustainable City Network, December 10, 2013. Accessed August 29, 2015.

- ^ a b c Gao, Su (March 26, 2013). "Can private equity fill the US water investment gap?". Bloomberg New Energy Finance: 1–11.

- ^ Henning, Rich. "United Water and KKR Sign Unique Utility Partnership with City of Bayonne, NJ (Press Release)" Archived July 5, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, United Water, December 20, 2012. Accessed August 29, 2015.

- ^ a b Corkery, Michael. "Private Equity Tries on the Hard Hat" Archived January 12, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, The Wall Street Journal, April 22, 2013. Accessed August 29, 2015.

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Bayonne,_New_Jersey

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk