A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

The government of Belarus is criticized for its human rights violations and persecution of non-governmental organisations, independent journalists, national minorities, and opposition politicians.[1][2] In a testimony to the United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, former United States Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice labeled Belarus as one of the world's six "outposts of tyranny".[3] In response, the Belarusian government called the assessment "quite far from reality".[4] During 2020 Belarusian presidential election and protests, the number of political prisoners recognized by Viasna Human Rights Centre rose dramatically to 1062 as of 16 February 2022.[5] Several people died after the use of unlawful and abusive force (including firearms) by law enforcement officials during 2020 protests.[6] According to Amnesty International, the authorities didn't investigate violations during protests but instead harassed those who challenged their version of events.[6] In July 2021, the authorities launched a campaign against the remaining non-governmental organizations, liquidating at least 270 of them by October, including all previously registered human rights organizations in the country.[7]

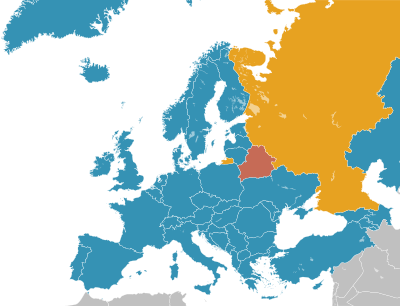

President Alexander Lukashenko has described himself as having an "authoritarian ruling style".[8] Western countries have described Belarus under Lukashenko as "Europe's last dictatorship"; the government has accused the same Western powers of attempting a regime change.[9] The Council of Europe has barred Belarus from membership since 1997 for undemocratic voting and election irregularities in the November 1996 constitutional referendum and parliament by-elections.[10]

Dozens of Belarusian government officials responsible for political repressions, forced disappearances, propaganda, and electoral fraud have been subject to personal sanctions by the United States of America and the European Union.

Electoral process

On 10 July 1994 Alexander Lukashenko was elected President of Belarus. He won 80.3% of the vote.

As of 2017, no other presidential or parliamentary election or referendum held in Belarus since then has been accepted as free and fair by the OSCE, the United Nations, the European Union or the United States. Senior officials responsible for the organization of elections, including the head of the Central Elections Commission, Lydia Yermoshina, were subject to international sanctions for electoral fraud:

| 9 September 2001 | 19 March 2006 | 19 December 2010 |

|---|---|---|

| 75.6% | 83% | 79.6% |

December 2010 election

The presidential elections of 2010 were followed by opposition protest and its violent crackdown by the police. A group of protesters tried to storm a principal government building, smashing windows and doors before riot police pushed them back.[11] After attack of principal building protesters were violently suppressed. Several hundreds of activists, including several presidential candidates, were arrested, beaten and tortured by the police and the KGB.

Lukashenko criticized the protesters, accusing them of "banditry".[12]

Police violence during the protests and the overall conduction of the election caused a wave of harsh criticism from the U.S. and the EU. More than 200 propagandists, state security officers, central election committee staff and other officials were included in sanctions lists of the European Union: they were banned from entering the EU and their assets in the EU, if any, were to be frozen.

August 2020 election

In June 2020, the Amnesty International documented clampdown on human rights, including the rights to freedom of expression and peaceful assembly and association, ahead of presidential elections scheduled for 9 August 2020. The organization reported politically motivated prosecutions, intimidation, harassment and reprisals against opposition candidates and their supporters. The Belarusian authorities targeted and intimidated civil society activists and independent media. Two politicians, Syarhei Tsikhanouski and Viktar Babaryka, were jailed and faced politically motivated criminal proceedings. Hundreds of peaceful protesters, including their supporters, were arbitrarily arrested and heavily fined or held in "administrative detention".[13][14] On 14 August 2020, the European Union imposed sanctions on individual Belarusian officials, after reports of the systematic abuse and torture of Belarusians in a violent crackdown on protesters. The Belarusian security forces beat and detained peaceful protesters, who participated in demonstrations against the official election outcome.[15]

Freedoms

Freedom of the press

Since the 2000s, Reporters Without Borders have been ranking Belarus below all other European countries in its Press Freedom Index.[16]

Freedom House has rated Belarus as "not free" in all of its global surveys since 1998, "Freedom in the World";[17][18] the Lukashenko government curtails press freedom, the organization says. State media are subordinate to the president. Harassment and censorship of independent media are routine.

Under the authoritarian president Alexander Lukashenko, journalists like Iryna Khalip, Natalya Radina, and Pavel Sheremet have been arrested for their work. Independent printed media like Nasha Niva have been excluded from state distribution networks.

In February 2021, two Belsat TV journalists Katsyaryna Andreeva and Darya Chultsova were imprisoned for two years for streaming during anti-Lukashenko protests in Minsk.[19]

In May 2021, top news site tut.by which was read by circa 40% of internet users in Belarus was blocked and several its journalists were detained.[20] In July 2021, Nasha Niva news site was blocked with simultaneous detention of the editors took place.[21] Editorial office of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty in Minsk was searched with doors being broke, homes of several its journalists were also searched.[22] Coverage of these attacks on independent media by state-run TV channels is considered to be an attempt to intimidate people. According to Current Time TV, state-run media made false accusations about the activities of journalists and invented fake evidences of their guilt without any trial.[23] Amnesty International condemned attack on NGOs by Belarusian authorities.[24]

In July 2021, registrations of Belarusian Association of Journalists, Press Club Belarus and Belarusian branch of writers' PEN center were revoked as a part of attack on NGOs (see #Pressure on NGOs section).[25]

Freedom of religion

Jews are not the only minority who are alleged to have had their human rights violated in Belarus. On 25 March 2004, the Associated Press reported that a ban exists on home worship in the country and that members of four Protestant churches had recently asked the government to repeal a 2002 law which forbade them worshipping from their own homes, although they were members of legally registered religions.[26] The Christian Post reported in a 21 April 2005 article[27] that non-denominational, charismatic churches were greatly affected by the law, since none of these churches own buildings. Protestant organizations have also complained of censorship because of the ban on importing literature without approval by government officials.

According to Forum 18, textbooks widely used in Belarusian schools (as of 2002) contain anti-religious views similar to those taught in the USSR:

Religion does not teach a believer to strive to lead a dignified life, to fight for his freedom or against evil and oppression. This is all supposed to be performed for him by supernatural forces, above all, god. All that is left for the believer to do is to be his pathetic petitioner, to behave as a pauper or slave...Religion's promises to give a person everything that he seeks in it are but illusion and deception."

The organization also reported that charismatic Protestant churches (such as Full Gospel) and Greek Catholic and independent Orthodox churches (such as those unaffiliated with the Russian Orthodox Church) have encountered difficulty in registering churches.[28]

In 2003 Protestant groups accused the government of Belarus of waging a smear campaign against them, telling Poland's Catholic information agency KAI that they had been accused of being Western spies and conducting human sacrifice.[29] Charter 97 reported in July 2004 that Baptists who celebrated Easter with patients at a hospital in Mazyr were fined and threatened with confiscation of their property.[30]

Only 4,000 Muslims live in Belarus, mostly ethnic Lipka Tatars who are the descendants of immigrants and prisoners in the 11th and 12th centuries.[31] The administration for Muslims in the country, abolished in 1939, was re-established in 1994.

However, Ahmadiyya Muslims (commonly regarded as a non-violent sect) are banned from practicing their faith openly in Belarus, and have a similar status to groups like Scientology and Aum Shinrikyo.[32] There have been no major reports of religious persecution of the Muslim community; however, because of the situation in Chechnya and neighboring Russia concerns have been expressed by Belarusian Muslims that they may become increasingly vulnerable.

These fears were heightened on 16 September 2005 when a bomb was detonated outside a bus stop, injuring two people. On 23 September a bomb was exploded outside a restaurant, wounding nearly 40 people. Muslims are not suspected in the latter attack, which was labeled "hooliganism".[33]

In 2020, the government pressed on major religious groups after they condemned violence during the mass protests. On 26 August 2020, Belarusian riot police OMON blocked protesters and random believers in a Roman Catholic church in Minsk for several hours.[34] The leader of the Belarusian Orthodox Church Metropolitan Paul was forced to resign after criticism of the police and authorities; his changer Veniamin was considered to be a much more comfortable figure for Lukashenko.[35][36] The leader of the Roman Catholic church in Belarus Tadevuš Kandrusievič was banned from returning to Belarus from Poland for several months and was forced to resign soon after the return.[37][38][34]

In 2021, the authorities organized the "All-Belarus prayer" convincing all confessions to make a prayer. Alexander Lukashenko tried to stop the performance of the religious song "The Almighty God" (Belarusian: Магутны Божа) warning Catholic priests not to perform it.[39] In 2021, an official newspaper of Minsk Region published a cartoon depicting Roman Catholic priests as Nazis wearing swastika instead of crosses.[40][34]

In 2023, Freedom House rated Belarus’ religious freedom as 1 out of 4.[41]

Freedom of association

The constitutional right of freedom of associations is not always implemented in practice. In 2013, Amnesty International characterized Belarusian legislation on registration of NGOs as "over-prescriptive".[42] Ministry of Justice of Belarus who is responsible for the registration of new organizations uses double standards for commercial and other non-governmental organizations, including political parties.[43] The former need only a declaration to start operations, the latter have to get a permission.[43] Political associations, including parties, however, had difficulties to get a permission. The last new party was registered in Belarus in 2000, because later the ministry denied to register new parties for different reasons.[44] Belarusian Christian Democracy made 7 attempts to register, Party of freedom and progress — 4 attempts; People's Hramada party was also prevented from registration.[44] The ministry justified all these cases by the reasons that are thought to be artificial and flimsy. For example, the ministry refused to register a local branch of BPF Party in Hrodna Region because of "incorrect line spacing" in the documents.[43][44] During another attempt to register this branch, the ministry requested the additional documents that are not mentioned in the law.[45] One of the refusals got by the Belarusian Christian Democracy cited lack of home or work phones information for some of the party founders.[44] Another refusal was based on a statement in the party's charter that its members should be "supporters of a Christian worldview".[42] Amnesty International reported cases of pressure to withdraw signatures needed to register a political party by the local authorities and managers (in state organizations).[42] Several activists (including Zmitser Dashkevich) were imprisoned for "the activity of unregistered associations".[42]

According to the Centre for Legal Transformation, the ministry is also actively refusing to register non-governmental organizations.[45] In 2009, the ministry declared that the registration process was simplified, but the legal experts of political parties doubted this statement claiming that only insignificant issues were affected.[43] In 2012, the ministry started the procedure of suspension of an NGO citing the wrong capital letter on a stamp ("Dobraya Volya" instead of "Dobraya volya") as one of the reasons; the NGO was soon suspended.[42] In 2011 and 2013, the ministry refused to register LGBT organizations; therefore Belarus had no LGBT associations.[42] Human rights organizations also fail to register, so the long-established Belarusian Helsinki Committee is the only registered organization in this area on the national level.[42]

In July and August 2021, Belarusian Ministry of justice started the procedure of closure of several major NGOs, including Belarusian Popular Front, the oldest continuously operating organization in Belarus (founded in 1988, registered in 1991),[46] Belarusian Association of Journalists,[47] Belarusian PEN centre.[48] The liquidation of the oldest green group in Belarus, Ecohome (Executive Director Marina Dubina), was condemned by 46 members of Aarhus Convention and by the European ECO Forum. The remaining members of the convention voted to give the Belarusian government a chance to cancel the liquidation before 1 December 2021, threatening to suspend its membership otherwise.[49]

Judicial system

Belarusian judicial system is characterized by the high conviction rate: in 2020, 99.7% of criminal cases resulted in conviction and only 0.3% — in acquittance. This rate is stable for several years.[50] The judicial system is especially severe to people expressing their views: among prosecuted people are journalists, civil activists, people who make political comments and jokes on social networks and put emojis there.[51] Among the most controversial "crimes" are white socks with a red stripe, white and red hair, 70 people arrested in Brest for dancing (some of them were sentenced to 2 years of prison).[52][53] Opposition leader also experience harsh treatment in the courthouses which is sometimes compared with the Stalinist trials.[51]

Capital punishment

Belarus is the only European country that continues to use capital punishment. The U.S. and Belarus were the only two of the 56 member states of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe to have carried out executions during 2011.[54]

Political dissidents and prisoners

In December 2010, Belarusian special security forces attacked demonstrators, beat and injured many activists with batons and arrested more than 600 people after a rally in central Minsk to protest the outcome of elections widely seen by Western observers as fraudulent. In their joint statement, Hillary Clinton and Baroness Ashton called for the immediate release of the protesters (including at least seven opposition presidential candidates) and strongly condemned what they termed the "disproportionate" use of force against demonstrators.

Belarus has come under attack from Amnesty International for its treatment of political prisoners,[55] including those from the youth wing of the Belarusian Popular Front (a pro-democracy party). In a report dated 26 April 2005 Amnesty criticised Belarus for its treatment of dissidents, including a woman imprisoned for publishing a satirical poem.[55] Another political prisoner who has been in jail for four years (June 2001 – August 2005) is Yury Bandazhevsky, a scientist who was jailed on accusations on taking bribes from students' parents, although Amnesty International has stated on their website "His conviction was widely believed to be related to his scientific research into the Chernobyl catastrophe and his open criticism of the official response to the Chernobyl nuclear reactor disaster on people living in the region of Gomel.".[56]

The United States Department of State issued a report on 14 April 2005 expressing concern about the disappearance (and possible execution) of the political activists Yury Zacharanka, Viktar Hanchar and Anatol Krasouski in 1999 and the journalist Dzmitry Zavadski in 2000, and continuing incidents of arrest and detention without trial. The State Department has also appealed to Belarus to provide information publicly about individuals who were executed.

A report dated 31 August 2005 from Amnesty USA claimed that, in addition to the Polish minority crisis earlier that year, three Georgians from the youth movement Kmara were detained while visiting Belarus.[57] The activists were detained on 24 August with Uladimir Kobets, from Zubr (a Belarusian opposition movement). According to the report, he was released after two hours after being told that the police operation was directed at "persons from the Caucasus".

The following activists and political leaders have been declared political prisoners at different times:

- Ales Bialiatski, Vice President of International Federation for Human Rights and head of Viasna Human Rights Centre[58]

- Mikola Statkevich

- Uladzimir Nyaklyayew

- Andrei Sannikov

- Paval Sieviaryniets

- Zmicier Dashkievich

- Andrei Kim

- Natalya Radina

- Iryna Khalip

- Alyaksandr Kazulin

- Mikalay Autukhovich

- Tsimafei Dranchuk

- Syarhei Parsyukevich

- Eduard Palčys

In 2017, the Viasna Human Rights Centre listed two political prisoners detained in Belarus, down from 11 in 2016.[59]

As of 3 July 2021, number of political prisoners recognized by Viasna rose to 529; as of 22 February — to 1078.[5]

Extrajudicial use of judiciary

As noted in the 2008 U.S. Department of State Report, while the Belarus Constitution[60] provides for the separation of powers, an independent judiciary and impartial courts (Articles 6 and 60), the government ignores these provisions when it suits its immediate needs; corruption, inefficiency and political interference are prevalent in the judiciary; the government convicts individuals on false and politically motivated charges, and executive and local authorities dictate the outcomes of trials; the judiciary branch lacks independence, and trial outcomes are usually predetermined; judges depend on executive-branch officials for housing; and the criminal-justice system is used as an instrument to silence human-rights defenders through politically motivated arrests, detention, lack of due process and closed political trials.[61]

Although Article 25 of the Belarus Constitution prohibits the use of torture, in practice Belarus tortures and mistreats detainees; while Article 26 provides for the presumption of innocence, defendants often must prove their innocence; while Article 25 prohibits arbitrary arrest, detention and imprisonment, Lukashenko's regime conducts arbitrary arrests, detention and imprisonment of individuals for political reasons; while Article 210(1) of the Criminal Procedure Code provides that a search warrant must be obtained before any searches, in practice authorities search residences and offices for political reasons; while Article 43 of the Criminal Procedure Code gives defendants the right to attend proceedings, confront witnesses, and present evidence on their own behalf, in practice these rights are disregarded. Prosecutors are not independent, and that lack of independence renders due-process protections meaningless; prosecutor authority over the accused is "excessive and imbalanced".[62][61]

- "Arbitrary arrests, detentions, and imprisonment of citizens for political reasons, criticizing officials, or for participating in demonstrations also continued. Some court trials were conducted behind closed doors without the presence of independent observers. The judiciary branch lacked independence and trial outcomes usually were predetermined".[61]

The section of the Report entitled "Arbitrary Arrest or Detention" noted that although "the law limits arbitrary detention ...the government did not respect these limits in practice authorities continued to arrest individuals for political reasons". It further notes that during 2008 "Impunity remained a serious problem"; "Police frequently detained and arrested individuals without a warrant"; "authorities arbitrarily detained or arrested scores of individuals, including opposition figures and members of the independent media, for reasons that were widely considered to be politically motivated".

The section titled "Denial of Fair Public Trial" noted: "The constitution provides for an independent judiciary; however, the government did not respect judicial independence in practice. Corruption, inefficiency, and political interference were prevalent in the judiciary. There was evidence that prosecutors and courts convicted individuals on false and politically motivated charges, and that executive and local authorities dictated the outcomes of trials".

- " judges depended on executive branch officials for personal housing".

- "A 2006 report by the UN special rapporteur on Belarus described the authority of prosecutors as "excessive and imbalanced" and noted "an imbalance of power between the prosecution and the defense".

- "defense lawyers cannot examine investigation files, be present during investigations, or examine evidence against defendants until a prosecutor formally brought the case to court";

- "lawyers found it difficult to call some evidence into question because technical expertise was under the control of the prosecutor's office";

These imbalances of power intensified at the beginning of the year "especially in relation to politically motivated criminal and administrative cases".

- "y presidential decree all lawyers are subordinate to the Ministry of Justice the law prohibits attorneys from private practice".

- "he law provides for the presumption of innocence; however, in practice defendants frequently had to prove their innocence;

- ” the law also provides for public trials; in practice, this was frequently disregarded; "defendants have the right to attend proceedings, confront witnesses, and present evidence on their own behalf; however, in practice these rights were not always respected";

- "courts often allowed information obtained from forced interrogations to be used against defendants".

International documents reflect that the Belarusian courts that are subject to an authoritarian executive apparatus, routinely disregard the rule of law and exist to rubber-stamp decisions made outside the courtroom; this is tantamount to the de facto non-existence of courts as impartial judicial forums. The "law" in Belarus is not mandatory, but optional and subject to discretion. Nominal "law" which, in practice, is not binding is tantamount to the non-existence of law.

Dealing with demonstrators and planned construction of concentration camps

Several violations of human rights were reported after the beginning of 2020 Belarusian protests. According to Amnesty International, human rights experts of the United Nations documented 450 evidences of torture, cruel treatment, humiliation, sexual abuse, restricted access to water, food, medical aid and hygiene products. Ban of contacts with lawyers and relatives became a common practice for the arrested.[63] Belarusian authorities acknowledged the receipt of nearly 900 complaints, but no criminal cases were initiated.[63] The authorities instead increased the pressure on human rights activists.[64]

In January 2021, an audio recording was released in which the commander of internal troops and deputy interior minister of Belarus Mikalai Karpiankou tells security forces that they can cripple, maim and kill protesters in order to make them understand their actions. This, he says, is justified because anyone who takes to the streets is participating in a kind of guerrilla warfare. In addition, he discussed the establishment of camps, surrounded by barbed wire, where protesters will be detained until the situation calms down. A spokeswoman for the Interior Ministry stamped the audio file as a fake.[65][66] However, a phonoscopic examination of the audio recording confirmed that the voice on the recording belongs to Karpiankou.[67] The Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe expressed its concern about the remarks.[68] According to Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, such a camp was indeed used near the town of Slutsk in the days from August 13 to 15, 2020. Many of those detained there are said to have been brought from the Okrestina prison in Minsk.[69]

Belarusian authorities published a number of videos with detained people confessing and repenting on camera; these video were presumably made under duress.[70] Roman Protasevich looked battered on his confession video and had cuts or bruisings on his wrists.[71][72] It was assumed that Roman's girlfriend Sofia Sapega was arrested only to put pressure on him.[73] Amnesty International's Eastern Europe and Central Asia Director Marie Struthers condemned the forced confession of Protasevich and claimed that it was the result of ill-treatment.[74] It was reported that pro-Lukashenko journalist of state-owned Sovetskaya Belorussiya – Belarus' Segodnya newspaper Lyudmila Gladkaya interrogated the arrested people together with police officers in several confession videos.[75]

In 2020, Belarusian KGB started to put Belarusian citizens on the list of terrorists (without court's decision). The first two were Nexta Telegram channel founders Stepan Putilo and Roman Protasevich. As of May 2021, the number of Belarusian people in the list was 37, including a Belarusian-American Yuras Zyankovich.[76] Terrorism can be punishable by death penalty in Belarus,[77] but at least some of the people in the list weren't accused of the appropriate Criminal Code article.[78]

On 1 October 2021, general and member of the lower chamber of the Belarusian parliament Oleg Belokonev called to murder 20–100 opposition activists as a revenge for deaths of state security officials.[79]

Pressure on lawyers

After the start of 2020 Belarusian protests, a number of lawyers (advocates) who defended opposition activists were disbarred (deprived of the advocate status) by the commission of the Ministry of justice: Alexander Pylchenko (lawyer of Viktar Babaryka and Maria Kalesnikava), Yuliya Levanchuk,[80] Lyudmila Kazak (lawyer of Maria Kalesnikava),[81] Sergey Zikracki (lawyer of Katsyaryna Andreeva).[82] At least three other lawyers were disbarred after arrests during protests or comments in the social networks.[83] This practice was criticized as violation of independence of the legal profession.[84] Official reasons of disbarment included "low level of knowledge" and "lack of qualification".[85] Opposition activists and lawyers Maxim Znak and Illia Salei (the latter was a former lawyer of Maria Kalesnikava) were arrested in September 2020 and recognized as prisoners of conscience by the Amnesty International.[86] Head of Belarusian Republican Bar Association and member of the Belarusian parliament Viktar Čajčyc fully supported the authorities and called lawyers "not to go to politics".[87][88][89] On 2 March 2021, the American Bar Association expressed "deep concern about the escalating attacks on the rule of law and the independence of the legal profession in Belarus".[90] In May 2021, ABA's Center for human rights analysed 4 cases of disbarment in Belarus and concluded that these acts represented intimidation, hindrance, harassment, improper interference with lawyers' functions and undermined the rule of law in Belarus.[91]

In May 2021, Belarusian parliament amended the laws on the legal profession (law 113-Z issued on 27 May 2021 signed by Lukashenko on 28 May and came into effect on 30 May).[92] The amendments banned individual advocates and law firms (bureaus), making the state-regulated judicial consultations the only form of provision of advocate services.[93] Ministry of justice was given the right to approve the candidates to presidiums of local bar associations and their heads.[93] It was also noted that one of the amendments could abolish free ("for 1 rubel") legal help to the arrested protesters.[93] The amendments were highly criticized by independent lawyers, human rights activists and legal experts.[93][94][95][88] Jurist Sergey Gasoyan claimed that the amendments "question the existence of advocacy as an institution that defends laws, rights and interests of citizens".[95] The amendments were compared with the abolishment of independent advocacy.[88][96] The law wasn't put up for public discussion, but at least 4,000 people signed the petition against the amendments.[88]

Lawyers of opposition figures reported several violations of law that prevented them to perform their duties. In December 2020, a lawyer was prohibited to be present at a search in his client's home.[97] Lawyer of Roman Protasevich couldn't see her client for 4 days after his detention in Minsk airport and later reported that she couldn't see him for a week.[98] Former investigator Yevgeny Yushkevich also wasn't allowed to meet his lawyer for the first 4 days after detention.[99] On 28 April 2021, state-owned ONT TV published a part of private conversation between Sergei Tikhanovsky and his lawyer Natallia Mackevich who later filed a complaint with the Attorney General about the violation of attorney privilege.[100]

Pressure on NGOs

On 14 July 2021, Belarusian authorities launched an attack on Belarus-based non-governmental organizations (NGOs) which resulted in dissolution of nearly 40 of them by the Ministry of justice and detention of several activists.[101] This campaign was described as "a total purge on civil society".[102] It was noticed that an attack on NGOs was launched immediately after meeting of Lukashenko and Vladimir Putin.[101]

Dissolved NGOs included "Imena" social and healthcare crowdfunding platform, several human rights activists groups (Center for legal transformation, Human Constanta, Youth Labor Rights, Gender Answer and others), journalists organizations (Belarusian Association of Journalists and Press Club Belarus), several cultural organizations including "Mova Nanova" Belarusian language courses and "Vedanta vada" organization promoting Indian culture and religion, Belarusian branch of writers' PEN center, IPM business school[103][25][102] Belarusian PEN center headed by the Nobel Prize laureate Svetlana Alexievich was dissolved by order of Supreme Court of Belarus on 9 August 2021.[104]

On 23 July 2021, Belarusian Helsinki Committee, Barys Zvozskau Belarusian Human Rights House, Viasna Human Rights Centre and 3 other human rights activists organizations issued a statement to "stop demolition of Belarus's civil society", claiming violations of the international obligations of Belarus in the field of freedom of association and expression.[105] On 24 September 2021, Supreme Court of Belarus liquidated the World Association of Belarusians which worked with the Belarusian diaspora organizations.[106]

The authorities also dissolved the major union of entrepreneurs "Perspektiva"[107] and eliminated the Union of Belarusian Writers which was thought to be a revenge of Lukashenko for the writers' independent position.[108][109]

On 1 October 2021, the Belarusian Helsinki Committee was forcibly liquidated by the Supreme Court. The court used materials of some unspecified criminal case (probably with no verdict passed so far) to dissolute the BHC. BHC was the pre-last registered human rights group in Belarus (the last one is Pravovaya iniciativa — The Legal Initiative, which is under of liquidation too).[110]

In December 2021, the Belarus Solidarity Foundation (BYSOL), a non-profit organization aimed at raising funds to provide financial aid to victims of repression in Belarus, was declared to be "extremist".[111]

Labour relations

The situation for trade unions and their members in the region has been criticized by Amnesty UK,[112] with allegations that authorities have interfered in trade-union elections and that independent trade-union leaders have been dismissed from their positions.

In 2021, International Trade Union Confederation listed Belarus among top 10 worst countries for working people in the world (Global Rights Index).[113] Reasons for worsening of the situation included state repression of independent union activity, arbitrary arrests, severe cases of no or restricted access to justice.[114] Belarus have already been among top 10 worst countries in Global Rights Index in 2015 and 2016.[114]

In June 2021, the International Labour Organization criticized the "blatant violation of international labour standards in Belarus" during the annual International Labour Conference.[115]

In recent years, trades unions in the country have been subject to a variety of restrictions, including:[116]

- Unregistered union ban

Beginning in 1999, all previously registered trade unions had to re-register and provide the official address of the headquarters (which often includes a business address). A letter from the management is also required, confirming the address (making the fate of the trade union dependent on the management). Any organization which fails to do so is banned and dissolved.

In 2021, International Trade Union Confederation claimed that the government "continued to deny registration to independent unions".[114]

- High minimum-membership requirement

In a measure which has also reportedly been used against Jewish human-rights organizations, the government announced that any new trade union must contain a minimum of 500 members for it to be recognized. This makes it difficult for new unions to be established.

- Systematic interference

The International Labour Organization's governing body issued a report in March 2001 complaining of systematic interference in trade union activities, including harassment and attacks on union assets. Workers who are members of independent trade unions in Belarus have, according to Unison, been arrested for distributing pamphlets and other literature and have faced losing their jobs.

Belarusian workers are systematically intimidated to leave independent trade unions, members of student independent unions are expelled from universities.[115] In 2021, the leader of the independent REP trade union was forced to leave Belarus after the office was raided by the police.[115]

In 2014 Lukashenko announced the introduction of new law that will prohibit kolkhoz workers (around 9% of total work force) from leaving their jobs at will – change of job and living location will require permission from governors. The law was compared with serfdom by Lukashenko himself.[117][118] Similar regulations were introduced for the forest industry in 2012.[119]

During 2020 Belarusian protests, several companies attempted to start a strike, but was met with brutal repression.[114] In 2021, three employees of Byelorussian Steel Works were imprisoned for attempting to organize a strike.[120]

On 28 May 2021 a law 114-Z was published that changed the Belarusian Labour code. It enabled to fire employees who served an arrest and who called to strike.[121] A number of reasons for temporarily suspension from work including "calling to stop performing other employees' duties without good reason" were also added.[121] Companies having any "hazardous production facilities" became completely prohibited to strike.[121] Political slogans during strikes became banned entirely.[122] WSWS characterized these amendments as making firing employees much easier.[122]

During 2020 Belarusian protests, offices of trade unions were raided by the police which forced unions to transfer personal information of the union members to the police.[114] Cases of abduction of union representatives on their way to work were reported.[114] In 2021, International Trade Union Confederation claimed that new government regulations can be seen as a "de facto ban on all public assemblies and strikes for unions".[114]

In September 2021, several workers of Grodno Azot, Belarusian Railway and Byelorussian Steel Works were detained. Their detention was connected with the threat of Alexander Lukashenko that workers who reveal the ways of bypassing the sanctions would be put in jail for a long time.[123] According to Nasha Niva, at least two of the detained persons were charged with high treason (article 356 of the Criminal Code of Belarus).[123]

Equality

Women's rightsedit

On 28 September 2021, during the government-led attack on NGOs (see #Pressure on NGOs), the Supreme Court of Belarus forcibly liquidated the "Gender Perspectives" NGO (Russian: Гендерные перспективы) which promoted the women rights in Belarus by withstanding gender discrimination and domestic violence. GP collaborated with the government on legal issues concerning women and hosted the national hot line for victims of domestic violence which took c. 15,000 calls in 10 years. After the court liquidated this organization, its team claimed that the government "doesn't care about the needs of a huge number of women experiencing domestic violence or gender discrimination".[124]

In 2023, female Canadian football player Patricia Lamanna terminated her contract with Belarusian football team FC Minsk over She left after 3 months over unpaid wages, a lack of provision for accommodation and an inability for her to use her Canadian credit card for transactoons in Belarus due to restrictions.[125]

Sexual orientationedit

Belarus legalized homosexuality in 1994; however, homosexuals face widespread discrimination.

In recent years, gay pride parades have been held in Minsk. One notable parade was staged in 2001, when presidential elections were held. However, according to OutRage! (a gay rights organization based in Britain), a gay-rights conference in 2004 was canceled after authorities threatened to arrest those taking part. The country's only gay club, Oscar, was closed in 2000 and in April 1999, the Belarus Lambda League's efforts to gain official registration was blocked by the Ministry of Justice. On 31 January 2005, the Belarusian national anti-pornography and violence commission announced that it would block two gay websites, www.gaily.ru and www.qguis.ru; they were said to contain obscene language and "indications of pornography".

In 1999, in an extraordinary conference entitled "The Pernicious Consequences of International Projects of Sexual Education", members of the Belarusian Orthodox Church reportedly accused UNESCO, the United Nations, and the World Health Organization of encouraging "perversion", "satanic" practices (such as the use of condoms) and abortion. One priest reportedly called for all homosexuals to be "executed on the electric chair".[citation needed]

In August 2004 the International Lesbian and Gay Association reported that the Belarusian authorities forced a gay cultural festival, Moonbow, to be canceled amid threats of violence; foreigners who participated in any related activities would be expelled from the country. In addition, neo-Nazi groups allegedly put pressure on the authorities to cancel the event. Bill Schiller, coordinator of the ILGCN, described the situation:

While the rest of Europe is moving forwards, this last dictatorship in Europe is trying to push its homosexual community into a 1930s Nazi style concentration camp", says Schiller. "Sweden and other democratic governments of Europe must react to the harassment, persecution and international isolation of human beings.

Several times the LGBT community were forbidden to hold pride parades in Belarus.[42] Several activists were detained in 2010 while trying to hold a gay pride after its prohibition.[42] In 2011 and 2013, the ministry refused to register LGBT organizations; therefore Belarus had no LGBT associations.[42] Cases of police raids on gay parties were reported, and LGBT activists were often interrogated in connection with different crimes.[42] One of the activists was beaten in the police station, but the prosecutor's office refused to start an investigation of this case.[42]

Ethnic discriminationedit

Antisemitismedit

In 2004, Charter'97 reported that on some government-job applications Belarusians are required to state their nationality.[126] This has been cited as evidence of state antisemitism in the region, as similar practices were allegedly used to discriminate[citation needed] against Jews in the USSR. They are also required to state information about their family and close relatives; this is alleged to be a breach of the constitution. Other countries (such as the United Kingdom) also ask applicants to state their ethnicity on application forms in many cases, although this information is usually used only for statistical purposes.

Belarus has been criticized by the Union of Councils for Jews in the Former Soviet Union, many American senators and human-rights groups for building a football stadium in Grodno on the site of a historic Jewish cemetery. A website, www.stopthedigging.org (since shut down), was set up to oppose the desecration of the cemetery. The Lukashenko administration also faced criticism on this issue from members of the National Assembly and Jewish organizations in Belarus.

In January 2004, Forum 18 reported that Yakov Gutman (president of the World Association of Belarusian Jewry) accused Lukashenko of "personal responsibility for the destruction of Jewish holy sites in Belarus", accusing authorities of permitting the destruction of a synagogue to build a housing complex, demolishing a former shul in order to build a multi-story car park and destroying two Jewish cemeteries. According to the report, he was detained by police and taken to a hospital after apparently suffering a heart attack.

In March 2004 Gutman announced that he was leaving Belarus for the U.S. in protest of state anti-Semitism. His view was echoed by a July 2005 report by UCSJ that a personal aide of the President (a former Communist Party ideologue, Eduard Skobelev) had published anti-Semitic books and promoted guns to solve what he termed the "Jewish problem". In 1997, Skobelev was given the title "Honored Figure of Culture" by Lukashenko and put in charge of the journal Neman.

The UCSJ's representative in Belarus, Yakov Basin, wrote a report detailing the authorities' alleged anti-Semitism.[127] Also, Yakov Basin said that the authorities were "pretending not to notice anti-Semitic tendencies among bureaucrats, ideologues and leaders of the Orthodox Church". He also reported about openly anti-Semitic books published by the Church.[128]

The only Jewish higher-education institute in Belarus (the International Humanities Institute of Belarusian State University) was closed in February 2004,[129] in what many local Jews believe is a deliberate act of antisemitism to undermine their educational rights and position in society. However, it is not the only educational institution to face closure in Belarus; the last independent university in the nation, the European Humanities University (a secular institution, which received funding from the European Union),[130] was closed in July 2004. Commentators have implied that this may be part of a wider move by Lukashenko to crush internal dissent.

Jewish observers cite antisemitic statements by legislators and other members of government and the failure of authorities in Belarus to punish perpetrators of antisemitic crime (including violent crime) as indicators of a policy of antisemitism in the state.[citation needed]

In 2007, Belarus president Lukashenko made an anti-Semitic comment about the Jewish community of Babrujsk:

"This is a Jewish city, and the Jews are not concerned for the place they live in. They have turned Babrujsk into a pigsty. Look at Israel - I was there."[131][132]

The comment provoked active criticism from Jewish leaders and in Israel; Lukashenko subsequently sent a delegation to Israel.

In 2015, Lukashenko made another comment during a three-hours-long TV address, criticizing the governor of the Minsk Region for not keeping Belarus's Jewish population "under control." He also called the Jews "white boned," meaning they do not enjoy menial work.[133]

In 2021, Alexander Lukashenko claimed that "the Jews have succeeded in making the whole world bow down to them" which was criticized by the foreign ministry of Israel.[134] In the same 2021, Belarusian government newspaper Belarus' Segodnya accused groups of Belarusian Jews of attempts to destabilize the situation in the country with the help of Jews abroad.[134]

Anti-Polonismedit

On 3 August 2005, an activist working for the Union of Poles (representing the Polish minority community) was arrested and given a 15-day jail sentence and Lukashenko accused the Polish minority of plotting to overthrow him. The former head of the Union of Poles, Tadeusz Gawin, was later given a second sentence for allegedly beating one of his cell-mates (a claim he denies).

The offices of the Union of Poles were raided on 27 July 2005 in a crisis which came to the surface the previous day, when Andrzej Olborski (a Polish diplomat working in Minsk) was expelled from the country—the third such expulsion in three months. Poland had accused Belarus of persecuting the 400,000 Poles who have been a part of Belarus since her borders were moved westward after the Second World War.

Antiziganismedit

Former police officer reported that Belarusian militsiya has informal rules for Romani people which include arbitrary check of documents, phone examination, house inspection without reason.[135] 80% of Romani people in Belarus claim that they faced antiziganism (antigypsyism) by the police which include arbitrary detention, multiple fingerprint registration, confiscation of vehicles.[135]

On 16 May 2019, GAI road police officer was found dead near Mahilioŭ. Immediately after that, massive raids on local Romani people was organized.[136] Up to 40 Romani people were detained.[137] Women were released after night at the police station, but men remained at the police station.[136] One of the released Romani woman said she was told that "men were going to be in jail until we police found the criminals."[136] It was later established that the GAI road police officer whose death led to these roundups committed suicide.[138] Minister of interior Igor Shunevich refused to apologize to the Romani community for this incident.[139] International Federation for Human Rights called for investigation of mass roundups of Roma people in Mahilioŭ.[138]

Discrimination of Belarusian speakersedit

Members of the Belarusian-speaking minority of Belarus has been complaining about discrimination of the Belarusian language in Belarus, the lack of Belarusian language education and consumer information in Belarusian, all that despite the official status of Belarusian language as a state language besides Russian.[140][141]

In its 2016 country human rights on Belarus report, the US State Department also stated that there was "discrimination against ... those who sought to use the Belarusian language."[142] "Because the government viewed many proponents of the Belarusian language as political opponents, authorities continued to harass and intimidate academic and cultural groups that sought to promote Belarusian and routinely rejected proposals to widen use of the language," the report said.[142]

Belarus has two official languages, but cases of trials in Russian despite defendants' petitions to use Belarusian language were reported.[143][144][145]

On 23 July 2021, Mova Nanova Belarusian language courses was forcibly disbanded.[146] In July 2021, the authorities conducted a search in the office of the Belarusian Language Society, and in August the Ministry of Justice applied for liquidation of this society in the Supreme Court of Belarus.[147]

Government-sponsored hostage-takingedit

One of the more notable examples of the Belarusian government's violation of human rights and international norms was the abduction, unlawful detainment and torture of American attorney Emanuel Zeltser[148] and his assistant, Vladlena Funk.[149] On 11 March 2008, Zeltser and Funk were abducted in London by Belarusian KGB agents. Both were drugged and flown to Belarus on a private jet belonging to Boris Berezovsky, a Russian oligarch and friend of Lukashenko who was wanted by Interpol for fraud, money-laundering, participation in organized crime and international financial crimes.[150] After landing in Minsk Zeltser and Funk were detained by Lukashenko's guard, according to the U.S. State Department.[151] They were transported to Amerikanka (the Stalin-era Belarusian KGB detention facility), where they were tortured, denied medication and told they would remain imprisoned indefinitely unless the U.S. lifted sanctions against Lukashenko. Zeltser and Funk were held hostage for 473 days and 373 days, respectively. Their seizure, torture and detention sparked international outrage and significant press coverage (apparently unexpected by Belarusian authorities).[152][153]

The U.S. Department of State and members of the U.S. Congress repeatedly demanded the release of the hostages. World leaders, the European Parliament and international human-rights organizations joined the U.S. call for the immediate release of Funk and Zeltser. Amnesty International issued emergency alerts on the "torture and other ill-treatment" of Zeltser.[154] Ihar Rynkevich, a Belarusian legal expert and Press Secretary of the Belarus Helsinki Commission, said in an interview: "This is yet another shameful case for the Belarusian judiciary for which more than one generation of Belarusian legal experts will blush."[155] A strongly worded letter from the New York City Bar Association to Lukashenko condemned KGB abuse of Zeltser and Funk and demanding their immediate release. The bar-association letter expressed "great concerned [sic] about the arrests and detention of Mr Zeltser and Ms Funk and the reports of physical mistreatment of Mr Zeltser" and stated that this was inconsistent with Belarus' obligations under international agreements, including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the Convention Against Torture and Other Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT). The letter also noted that the charges the KGB brought against Zeltser and Funk "appears to have no basis to it", lacks "any explanation or detail" and "concerns have thus been reported that this is a fabricated charge, created to justify their unlawful detention".[156]

Neither Funk nor Zeltser had been lawfully "arrested", "charged", "indicted", "tried" or "convicted" under Belarusian or international law. They were unlawfully seized and held hostage, in violation of international law and Belarusian law. During their detention Funk and Zeltser were subjected to torture and cruel, inhuman or undignified treatment, in violation of Article 25 of the Belarus Constitution;[157] U.S. law and international treaties, including the International Convention Against the Taking of Hostages (the Hostage Convention);[158] the United Nations Convention Against Torture;[159] the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR);[160] the United Nations Convention Against Torture (the Torture Convention);[161] and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR).[160] Zeltser's and Funk's abduction, detention and mistreatment in KGB captivity was an attempt to coerce the United States to lift sanctions against Lukashenko (and other members of the Belarusian government) and against the Belarusian petrochemical company Belneftekhim (which they owned). Belarus's actions were gross violations of the law of nations and universally accepted norms of the international law of human rights, including laws prohibiting hostage-taking and state-sponsored terrorism.[162]

Yielding to the demands of the international community, Lukashenko released Funk on 20 March 2009 and Zeltser on 30 June (when a delegation from the U.S. Congress traveled to Belarus to meet with Lukashenko regarding the hostage crisis).[163] U.S. chargé d'affaires in Belarus Jonathan Moore commented after their release: "At no time have the Belarusian authorities ever provided any indication that the charges against Mr Zeltser and Ms Funk were legitimate. As a result, I can only conclude that the charges in this case are thoroughly without merit; and are the result of extra-legal motivation."[164]

Although the U.S. Department of State repeatedly said that it does not use its citizens as "bargaining chips", many in Belarus still believe that the U.S. made a deal with Lukashenko (inducing him to release the hostages in exchange for IMF credits to Belarus). Appearing on Russian TV network NTV, Anatoly Lebedko (Chairman of the Belarusian United Popular Party) said: "Washington was forced to pay ransom for its citizen [sic] by providing Lukashenko the IMF credits, pure and simple; in essence, this is hostage-taking, the practice, which is widespread in Belarus elevated to international level, where Lukashenko is not only sending a political message but demands monetary compensation for human freedom."[165]

Forced disappearancesedit

In 1999 opposition leaders Yury Zacharanka and Viktar Hanchar together with his business associate Anatol Krasouski disappeared. Hanchar and Krasouski disappeared the same day of a broadcast on state television in which President Alexander Lukashenko ordered the chiefs of his security services to crack down on "opposition scum". Although the State Security Committee of the Republic of Belarus (KGB) had them under constant surveillance, the official investigation announced that the case could not be solved. The investigation of the disappearance of journalist Dzmitry Zavadski in 2000 has also yielded no results. Copies of a report by the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, which linked senior Belarusian officials to the cases of disappearances, were confiscated.[166]

In September 2004, the European Union and the United States issued travel bans for five Belarusian officials suspected in being involved in the kidnapping of Zacharanka: Interior Affairs Minister Vladimir Naumov, Prosecutor General Viktor Sheiman, Minister for Sports and Tourism Yuri Sivakov, and Colonel Dmitry Pavlichenko from the Belarus Interior Ministry.[167]

In December 2019, Deutsche Welle published a documentary film in which Yury Garavski, a former member of a special unit of the Belarusian Ministry of Internal Affairs, confirmed that it was his unit which had arrested, taken away and murdered Zecharanka and that they later did the same with Viktar Hanchar and Anatol Krassouski.[168]

Ranking by human rights organizationsedit

Major human rights organizations have been criticizing Belarus and its human rights situation. For most of Lukashenko's tenure, he has been reckoned as leading one of the most repressive regimes in the world.

| 2021 | 2020 | 2019 | 2018 | 2017 | 2016 | 2015 | 2014 | 2013 | 2012 | 2011 | 2010 | 2009 | 2008 | 2007 | 2006 | 2005 | 2004 | 2003 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freedom in the World[169][170] | Not free (aggregate score: 11/100) | Not free (aggregate score: 19/100) | Not free (aggregate score: 19/100) | Not free (aggregate score: 21/100) | Not free (aggregate score: 20/100) | Not free (aggregate score: 17/100) | Not free | Not free | Not free | Not free | Not free | Not free | Not free | Not free | Not free | Not free | Not free | Not free | Not free |

| Index of Economic Freedom | Repressed (58.1, world rank 108) | Repressed | Mostly unfree | Repressed | Repressed | Repressed | |||||||||||||

| Press Freedom Index[171] | (Global rank: 158) 50.82 |

(Global rank: 153) 49.75 |

(Global rank: 153) |

(Global rank: 155) 52.59 |

(Global rank: 153) 52.43 |

(Global rank: 157) 54.32 |

(Global rank: 157) 47.98 |

(Global rank: 157) 47.81 |

(Global rank: 157) 48.35 |

(Global rank: 168) 99.00 |

(Global rank: 154) 57.00 |

(Global rank: 151) 59.50 |

(Global rank: 154) 58.33 |

(Global rank: 151) 63.63 |

(Global rank: 151) 57.00 |

(Global rank: 152) 61.33 |

(Global rank: 144) 54.10 |

(Global rank: 151) 52.00 |

(Global rank: 124) 52.17 |

| Democracy Index | Authoritarian | Authoritarian | Authoritarian | Authoritarian | Authoritarian | Authoritarian | Authoritarian | Authoritarian | Authoritarian | Authoritarian | Authoritarian | Authoritarian | Authoritarian | ||||||

| Freedom of the Press (report) |

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Antisemitism_in_Belarus Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Analytika

Antropológia Aplikované vedy Bibliometria Dejiny vedy Encyklopédie Filozofia vedy Forenzné vedy Humanitné vedy Knižničná veda Kryogenika Kryptológia Kulturológia Literárna veda Medzidisciplinárne oblasti Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy Metavedy Metodika Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok. www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk |