A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

This article may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. When this tag was added, its readable prose size was 29,000 words. (October 2023) |

The Blockade of Germany (1939–1945), also known as the Economic War, involved operations carried out during World War II by the British Empire and by France in order to restrict the supplies of minerals, fuel, metals, food and textiles needed by Nazi Germany – and later by Fascist Italy – in order to sustain their war efforts. The economic war consisted mainly of a naval blockade, which formed part of the wider Battle of the Atlantic, but also included the bombing of economically important targets and the preclusive buying of war materials from neutral countries in order to prevent their sale to the Axis powers.[1][page needed]

The blockade had four distinct phases:[1][failed verification]

- The first period, from the beginning of European hostilities in September 1939 to the end of the "Phoney War", saw both the Allies and the Axis powers intercepting neutral merchant ships to seize deliveries en route to their respective enemies. Naval blockade at this time proved less than effective because the Axis could get crucial materials from the Soviet Union until June 1941, while Berlin used harbours in Spain to import war materials into Germany.

- The second period began after the rapid Axis occupation of the majority of the European landmass (Scandinavia, Benelux, France and the Balkans) in 1940–1941, resulting in Axis control of major centres of industry and agriculture.

- The third period started in December 1941 after the attack on Pearl Harbor by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service brought the U.S. officially into the European war.

- The final period came after the tide of war finally turned against the Axis after heavy military defeats up to and after D-Day in June 1944, which led to gradual Axis withdrawals from the occupied territories in the face of the overwhelming Allied military offensives.

Historical background

At the beginning of the First World War in 1914, the United Kingdom used its powerful navy and its geographical location to dictate the movement of the world's commercial shipping.[2] Britain dominated the North Sea, the Atlantic Ocean, the Mediterranean Sea and, due to its control of the Suez Canal with France, access into and out of the Indian Ocean for the allied ships, while their enemies were forced to go around Africa. The Ministry of Blockade published a comprehensive list of items that neutral commercial ships were not to transport to the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, and the Ottoman Empire).[1] This included food, weapons, gold and silver, flax, paper, silk, copra, minerals such as iron ore and animal hides used in the manufacture of shoes and boots. Because Britain and France together controlled 15 of the 20 refuelling points along the main shipping routes, they were able to threaten those who refused to comply, by the withdrawal of their bunker fuel control facilities.[3]

In World War I, neutral ships were subject to being stopped to be searched for contraband. A large force, known as the Dover Patrol patrolled at one end of the North Sea while another, the Tenth Cruiser Squadron waited at the other. The Mediterranean Sea was effectively blocked at both ends and the dreadnought battleships of the Grand Fleet waited at Scapa Flow to sail out and meet any German offensive threat. Late in the war a large minefield, known as the Northern Barrage, was deployed between the Faroes and the coast of Norway to further restrict German ship movements.[4]

Britain considered naval blockade to be a completely legitimate method of war,[1] having previously deployed the strategy in the early nineteenth century to prevent Napoleon's fleet from leaving its harbours to attempt an invasion of England – Napoleon had also blockaded Britain. Germany in particular was heavily reliant on a wide range of foreign imports and suffered very badly from the blockade. Its own substantial fleet of modern warships was hemmed into its bases at Kiel and Wilhelmshaven and mostly forbidden by the leadership from venturing out.[1] Germany carried out its own immensely effective counter-blockade during its war on Allied commerce (Handelskrieg), its U-boats sinking many Allied merchant ships. By 1917 this had almost swung the war the way of the Central Powers.[1] But because Britain found an answer in the convoy system, the sustained Allied blockade led to the collapse and eventual defeat of the German armed forces by late 1918.

Build-up to World War II

In 1933 Adolf Hitler became Chancellor of Germany and, following the remilitarization of the Rhineland, the Anschluss with Austria and the later occupation of Czechoslovakia, many people began to believe that a new "Great War" was coming,[5] and from late 1937 onwards Sir Frederick Leith-Ross, the British government's chief economics advisor, began to urge senior government figures to put thought into a plan to revive the blockade so that the Royal Navy – still the world's most powerful navy – would be ready to begin stopping shipments to Germany immediately once war was declared.[3] Leith-Ross had represented British interests abroad for many years, having embarked on a number of important overseas missions to countries including Italy, Germany, China and Russia, experience which gave him a very useful worldwide political perspective. His plan was to revive the original World War I blockade but to make it more streamlined, making better use of technology and Britain's vast overseas business and commercial network so that contacts in key trading locations such as New York, Rio de Janeiro, Tokyo, Rome or Buenos Aires could act as a vast information gathering system. Making use of tip-offs provided by a vast array of individuals such as bankers, merchant buyers, waterfront stevedores and ship operators doing their patriotic duty, the Navy could have priceless advance knowledge of which ships might be carrying contraband long before they reached port.

Initially the Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, was not keen on the idea and still hoped to avoid war, but following his appeasement of Hitler at Munich in September 1938, which was widely seen as a stopgap measure to buy time, he too began to realise the need for urgent preparations for war. During the last 12 months of peace, Britain and France carried out a vigorous buildup of their armed forces and weapons production. The long-awaited Spitfire fighter began to enter service, the first of the new naval vessels ordered under the 1936 emergency programme began to join the fleet, and the Air Ministry made the final touches to the Chain Home early warning network of radio direction-finding (later called radar) stations, to bring it up to full operational readiness.

A joint British–French staff paper on strategic policy issued in April 1939 recognised that, in the first phase of any war with Germany, economic warfare was likely to be the Allies' only effective offensive weapon.[6] The Royal Navy war plans, delivered to the fleet in January 1939 set out three critical elements of a future war at sea.[7] The most fundamental consideration was the defence of trade in home waters and the Atlantic in order to maintain imports of the goods Britain needed for her own survival. Of secondary importance was the defence of trade in the Mediterranean and Indian Ocean. If Italy, as assumed also declared war and became an aggressive opponent, her dominating geographical position might force shipping to go the long way around the Cape of Good Hope (South Africa), but it was hoped to contain her with a strong fleet in the Mediterranean. Finally, there was the need for a vigorous blockade against Germany and Italy.

Pre-war situation in Germany

In Germany, where Hitler had warned his generals and party leaders that there would eventually be another war as early as 1934,[8] there was great concern about the potential effects of a new blockade. In order to force Germany to sign the Treaty of Versailles, the original blockade was extended for an additional nine months after the end of the fighting in October 1918.[citation needed] This course of action, which Hitler called "the greatest breach of faith of all time",[9] caused horrendous suffering among the German people and, according to some authors, led to an estimated half a million deaths from starvation.[10][11][12] Germany also lost its entire battle fleet of modern warships at the end of the war and although new ships were being built as fast as was practical – the battleships Bismarck and Tirpitz had been launched but not yet completed – they were in no position to face the British and French navies on anything like equal terms.

Triangles mark points at which nations suspended gold convertibility and/or devalued their currency against gold.

Greatly deficient in natural resources, Germany's economy traditionally relied on importing raw materials to manufacture goods for re-export, and she developed a reputation for producing high quality merchandise. By 1900 Germany had the biggest economy in Europe and she entered the war in 1914 with plentiful reserves of gold and foreign currency and good credit ratings. But by the end of the war, though the UK also lost a quarter of its real wealth,[13] Germany was ruined and she had since then experienced a number of severe financial problems; first hyperinflation caused by the requirement to pay reparations for the war, then – after a brief period of relative prosperity in the mid-1920s under the Weimar Republic – the Great Depression, which followed the Wall Street Crash of 1929, which in part led to the rise in political extremism across Europe and Hitler's seizure of power.

Although Hitler was credited with lowering unemployment from 6 million (some sources claim the real figure was as high as 11m) to virtually nil by conscription and by launching enormous public works projects (similar to Roosevelt's New Deal), as with the Autobahn construction he had little interest in economics and Germany's "recovery" was in fact achieved primarily by rearmament and other artificial means conducted by others. Because Germany was nowhere as wealthy in real terms as she had been a generation earlier, with very low reserves of foreign exchange and zero credit,[14] Hjalmar Schacht, and later Walther Funk, as Minister of Economy used a number of financial devices – some very clever – to manipulate the currency and gear the German economy towards Wehrwirtschaft (War Economy). One example was the Mefo bill, a kind of IOU produced by the Reichsbank to pay armaments manufacturers but which was also accepted by German banks. Because Mefo bills did not figure in government budgetary statements, they helped maintain the secret of rearmament and were, in Hitler's own words, merely a way of printing money.[citation needed] Schacht also proved adept at negotiating extremely profitable barter deals with many other nations, supplying German military expertise and equipment in return.

The Nazi official who took the leading role in preparing German industry for war was Hermann Göring. In September 1936 he established the Four Year Plan, the purpose of which was to make Germany self-sufficient and impervious to blockade by 1940. Using his contacts and position, as well as bribes and secret deals he established his own vast industrial empire, the Hermann Göring Works, to make steel from low-grade German iron ore, swallowing up small Ruhr companies and making himself immensely rich in the process.[15] The works were located in the area bounded by Hanover, Halle and Magdeburg, which was considered safe from land offensive operations, and a programme was initiated to relocate existing crucial industries nearest the borders of Silesia, Ruhr and Saxony to the more secure central regions. The great Danube, Elbe, Rhine, Oder, Weser, Main and Neckar rivers were dredged and made fully navigable, and an intricate network of canals was built to interlink them and connect them to major cities.[16]

While the armed forces were being built up, imports were reduced to the barest minimum required, severe price and wage controls were introduced, unions outlawed and, aware that certain commodities would be difficult to obtain once the blockade began, deals were made with Sweden, Romania, Turkey, Spain, Finland and Yugoslavia to facilitate the stockpiling of vital materials such as tungsten, oil, nickel, wool and cotton that would be needed to supply the armed forces in wartime. Heavy investment was made in ersatz (synthetic) industries to produce goods from natural resources Germany did have, such as textiles made from cellulose, rubber and oil made from coal, sugar and ethyl alcohol from wood, and materials for the print industry produced from potato tops. There were also ersatz foodstuffs such as coffee made from chicory and beer from sugar beet. Germany also invested in foreign industries and agricultural schemes aimed at directly meeting their particular needs, such as a plan to grow more soya beans and sunflower instead of maize in Romania.[17]

The American journalist William L. Shirer, who had lived in Berlin since 1934 and who made regular radio broadcasts to the US for CBS, noted that there were all kinds of shortages even before the war began.[18] Germany produced 85% of its own food and UK 91%. Still, even after rationing, food portions were insufficient even for hard labour workers. On 24 August 1939, a week before the invasion of Poland which started the war, Germany announced rationing of food, coal, textiles and soap, and Shirer noted that it was this action above all which made the German people wake up to the reality that war was imminent.[18] They were allowed one bar of soap per month, and men had to make one tube of shaving foam last five months. Housewives soon spent hours standing in line for supplies; shopkeepers sometimes opened otherwise non-perishable goods such as tinned sardines in front of customers when they were bought to prevent hoarding. The clothing allowance was so meagre that for all practical purposes people had to make do with whatever clothing they already possessed until the war was over. Men were allowed one overcoat and two suits, four shirts and six pairs of socks, and had to prove that the old ones were worn out to get new. Some items shown on the coupons, such as bed sheets, blankets and table linen could in reality only be obtained on production of a special licence.

Although the Nazi leadership maintained that the Allied strategy of blockade was illegal, they nevertheless prepared to counter it by all means necessary. In an ominous foreshadowing of the unrestricted submarine warfare to come, the Kriegsmarine (navy) sent out battle instructions in May 1939 which included the ominous phrase "fighting methods will never fail to be employed merely because some international regulations are opposed to them".[7]

First phase

This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2017) |

Hitler invaded Poland on 1 September 1939, and Britain and France declared war two days later. Within hours the British liner Athenia was torpedoed by U-30 off the Hebrides with the loss of 112 lives, leading the Royal Navy to assume that unrestricted U-boat warfare had begun.

Although France, unlike Britain, was largely self-sufficient in food and needed to import few foodstuffs, she still required extensive overseas imports of weapons and raw materials for her war effort and there was close co-operation between the two allies. As in World War I, a combined War Council was formed to agree strategy and policy, and just as the British Expeditionary Force, which was quickly mobilised and sent to France was placed under overall French authority, so various components of the French navy were placed under Admiralty control.

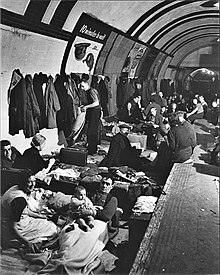

In Britain it was widely believed that the bombing of big cities and massive civilian casualties would commence immediately after the declaration.[19] In 1932 the MP Stanley Baldwin made a famous speech in which he said that "The bomber will always get through". This message sank deeply into the nation's subconsciousness, but when attacks did not come immediately, hundreds of thousands of evacuees gradually began to make their way home over the next few months.

Scapa Flow was again selected as the main British naval base because of its great distance from German airfields, however the defences built up during World War I had fallen into disrepair. During an early visit to the base, Churchill was unimpressed with the levels of protection against air and submarine attack, and was astounded to see the flagship HMS Nelson putting to sea with no destroyer escort because there were none to spare. Efforts began to repair the peacetime neglect, but it was too late to prevent a U Boat creeping into the Flow during the night of 14 October and sinking the veteran battleship Royal Oak with over 800 fatalities.

Although U-boats were the main threat, there was also the threat posed by surface raiders to consider; the three "pocket battleships" which Germany was allowed to build under the Versailles Treaty had been designed and built specifically with attacks on ocean commerce in mind. Their strong armour, 11 inch guns and 26-knot (48 km/h) speed enabled them to out-match any British cruiser, and two of them, the Admiral Graf Spee and the Deutschland had sailed between 21 and 24 August and were now loose on the high seas having evaded the Northern Patrol, the navy squadron that patrolled between Scotland and Iceland. The Deutschland remained off Greenland waiting for merchant vessels to attack, while the Graf Spee rapidly travelled south across the equator and soon began sinking British merchant ships in the southern Atlantic. Because the German fleet had insufficient capital ships to mount a traditional line of battle, the British and French were able to disperse their own fleets to form hunting groups to track down and sink German commerce raiders, but the hunt for the two raiders was to tie down no less than 23 important ships along with auxiliary craft and additional heavy ships to protect convoys.[citation needed]

At the start of the war a large proportion of the German merchant fleet was at sea, and around 30% sought shelter in neutral harbours where they could not be attacked, such as in Spain, Mexico, South America, the United States, Portuguese East Africa and Japan[citation needed]. 28 German bauxite ships were holed up in Trieste and, while a few passenger liners, such as the New York, St Louis and Bremen managed to creep home, many ended up stranded with goods deteriorating or rotting in their holds and with Allied ships waiting to capture or sink them immediately if they tried to leave port. The Germans tried various ways of avoiding the loss of the ships, such as disguising themselves as neutral vessels or selling their ships to foreign flags, but international law did not allow such transactions in wartime[citation needed]. Up to Christmas 1939, at least 19 German merchant ships were scuttled by their crews to prevent them from being taken by the Allies.[20] The pocket battleship Graf Spee herself was scuttled outside Montevideo, Uruguay, where she sought repairs to damage sustained during the Battle of the River Plate, after the British spread false rumours of the arrival of a vast naval force tasked to sink her, an early success for the Royal Navy.

Contraband control

The day after the declaration, the British Admiralty announced that all merchant vessels were now liable to examination by the naval Contraband Control Service and by the French Blockade Ministry, which put its ships under British command.[21] Because of the terrible suffering and starvation caused by the original use of the strategy, a formal declaration of blockade was deliberately not made,[22] but the communiqué listed the types of contraband of war that was liable for confiscation if carried. It included all kinds of foodstuffs, animal feed, forage, and clothing, and articles and materials used in their production. This was known as Conditional Contraband of War. In addition, there was Absolute Contraband, which constituted:

- All ammunition, explosives, chemicals or appliances suitable for use in chemical warfare

- Fuel of all kinds and all contrivances for means of transportation on land, in water or the air

- All means of communication, tools, implements and instruments necessary for carrying on hostile operations

- Coin, bullion, currency and evidences of debt

The Royal Navy selected three locations on home soil for Contraband Control: Weymouth and The Downs in the South to cover the English Channel approaches, and Kirkwall in Orkney to cover the North Sea. If ships were on government charter or sailing directly to Allied ports to unload cargo or passengers, they would not be detained any longer than was necessary to determine their identity, but if on other routes they were to stop at the designated contraband control ports for detailed examination. Ships proceeding eastward through the English Channel with the intention of passing the Downs, if not calling at any other Channel port, should call at Weymouth for contraband control examination.[23] Ships bound for European ports or en route to the North of Scotland should call at Kirkwall.

Three further British contraband inspection facilities were established at Gibraltar to control access into and out of the western Mediterranean, Haifa at the other end of the Mediterranean in Northern Palestine, and Aden on the Indian Ocean coast of Yemen at the southern entrance to the Red Sea to control access into the Mediterranean via the Suez Canal. To patrol the Mediterranean and the Red Sea access to the Indian Ocean, Britain would work together with the French, whose own navy was the world's fourth largest, and comprised a good number of modern, powerful vessels with others nearing completion. It was agreed that the French would hold the Western Mediterranean Basin via Marseilles and its base at Mers El Kébir (Oran) on the coast of Algeria, while the British would hold the Eastern Basin via its base at Alexandria. The Allies had practical control over the Suez Canal which provided passage between the eastern Mediterranean and the Indian Ocean via Port Said at the northern entry to the canal. The canal, built largely by French capital, at that time came under British jurisdiction as a result of the Anglo-Egyptian treaty of 1936.

The work of the actual inspection of cargoes was carried out by customs officers and Royal Naval officers and men who, together with their ships, were assigned to Contraband Control for various periods of duty. The job of Control Officer required great tact in the face of irate and defiant neutral skippers, particularly Dutch and Scandinavians who had a long tradition of trade with Germany. Contraband Control patrols dotted all practical sea routes, stopping all neutral ships, and making life very difficult for any who tried to slip by, forcing them into ports and laying them up for days before inspection, in some cases ruining perishable goods. Control ports were often very overcrowded, teleprinters constantly sending out cargo listings and manifests to be checked against import quota lists. Even for innocent ships, a delay of a day or two was inevitable; Contraband Control officers were under instructions to be extremely polite and apologetic to all concerned. Neutral captains often expressed utter astonishment and bemusement at the level of British advance knowledge of their activities, and soon realised it was hard to hide anything. Although numerous attempts were made to bypass the blockade, the net was extremely hard to avoid, and most neutral captains voluntarily stopped at one of the eight Allied Contraband Control ports.[24]

Ministry of Economic Warfare

The job of co-ordinating the various agencies involved in the blockade was carried out by the Ministry of Economic Warfare (MEW), which in the last few weeks before the outbreak of war had been set up by Frederick Leith-Ross. Leith-Ross had not been put off by Chamberlain's initially lukewarm reception to his plan to revive the blockade, but had in fact spent the time after Munich to continue his preparations regardless. Leith-Ross recruited shrewd bankers, statisticians, economists and experts in international law and an army of over 400 administrative workers and civil servants for his new ministry.[3] It was their job to compile and sift through the raw intelligence being received from the various overseas and other contacts, to cross-reference it with the known data on ship movements and cargoes and to pass on any relevant information to Contraband Control. They also put together the Statutory List – sometimes known as the "blacklist" – of companies known to regularly trade with, or who were directly financed by, Germany. In mid-September the Ministry published a list of 278 pro-German persons and companies throughout the world with whom British merchants and shipowners were forbidden to do business, subject to heavy penalties. When shipments from these companies were detected they were usually made a priority for interception.

One lesson that was learnt from World War I was that although the navy could stop ships on the open seas, little could be done about traders who acted as the middleman, importing materials the Nazis needed into their own neutral country then transporting it overland to Germany for a profit.[25] Leith–Ross spent the months before the war compiling a massive dossier on the annual quantities of materials the countries bordering Germany normally imported so that if they exceeded these levels in wartime, pressure could be brought on the authorities in those countries to take action. Diplomats from the Scandinavian nations, as well as Italy and the Balkan countries, who were also major suppliers to Germany, were given quota lists of various commodities and told they could import these amounts and no more, or action would be taken against them.

A ship stopping at a Control port raised a red and white flag with a blue border to signify that it was awaiting examination. At night the port authorities used signal lights to warn a skipper he must halt, and the flag had to stay raised until the ship was passed. Arrangements for boarding and examining ships were made in the port "Boarding Room", and eventually a team of 2 officers and 6 men set out in a fishing drifter or motor launch to the ship. After apologising to the captain for the trouble, they inspected the ship's papers, manifest and bills of lading. At the same time the wireless cabin was sealed so no signals could be sent out while the ship was in the controlled zone. After satisfying themselves that the cargo corresponded with the written records, the party returned ashore and a summary of the manifest, passengers, ports of origin and destination was sent by teleprinter to the Ministry. When the ministry's consent was received, the ship's papers were returned to the captain along with a certificate of naval clearance and a number of special flags – one for each day – signifying that they had already been checked and could pass other patrols and ports without being stopped. If the Ministry found something suspicious, the team returned to examine the load. If part or all the cargo was found suspect the ship was directed to a more convenient port where the cargo was made a ward of the Prize Court by the Admiralty Marshall who held it until the Court sat to decide the outcome, which could include returning it to the captain or confirming its confiscation to be sold at a later time and the proceeds placed into a prize fund for distribution among the fleet after the war. A disgruntled captain could dispute the seizure as illegal, but the list of banned goods was intentionally made broad to include "any goods capable of being used for or converted to the manufacture of war materials".

In the first four weeks of the war, official figures stated that the Royal Navy confiscated 289,000 tons of contraband and the French Marine Nationale 100,000 tons. The Germans responded with their own counter-blockade of supplies destined for Allied ports and published a contraband list virtually identical to the British list.[26] All neutral traffic from the Baltic Sea was to pass through the Kiel Canal for inspection, but with a fraction of the naval forces of their enemies, the action was more in defiance, but it was destined to have a big impact on neutral Scandinavian shipping, who among other materials supplied Britain with large quantities of wood pulp for explosive cellulose and newsprint. Germany began by targeting the Norwegian, Swedish and Finnish pulp boats, sinking several before Sweden shut down its pulp industry and threatened to stop sending Germany iron ore unless the attacks ceased.[27] Germany then began seizing Danish ships carrying butter, eggs and bacon to Britain, in breach of a promise to allow Denmark to trade freely with her enemies.

Up to 21 September 1939 over 300 British and 1,225 neutral ships had been detained, with 66 of them having cargo confiscated. In many cases these cargoes proved useful for the Allies' own war effort – Contraband Control also intercepted a consignment of 2 tons of coffee destined for Germany, where the population had long been reduced to drinking substitutes not made from coffee beans at all. When the manifest of the Danish ship Danmark, operated by the Halal Shipping Company Ltd, was inspected, the recipient was listed as none other than "Herr Hitler, President Republique Grand Allemagne".[23] From the beginning of the war to the beginning of October the daily average number of neutral ships stopping voluntarily at Weymouth was 20, out of which 74, carrying 513,000 tons, were examined; 90,300 tons of contraband iron ore, wheat, fuel oil, petrol and manganese were seized.[28] Even more was done at the other two contraband stations at Orkney and Kent.

Shipping shortage

At the beginning of the war, Germany possessed 60 U-boats, but was building new vessels quickly and would have over 140 by the summer of 1940. While Britain could call on impressive flotillas of battleships and cruisers for direct ship to ship confrontations, these heavy vessels were of limited use against U Boats. Britain now retained less than half the total of 339 destroyers she had at the height of the battle in 1917 when the U-boats almost forced Britain to consider surrender.

Orders were immediately placed for 58 of a new type of small escort vessel called the corvette which could be built in 12 months or less. Motor launches of new Admiralty design were brought into service for coastal work, and later, a larger improved version of the corvette, the frigate was laid down. To free up destroyers for oceangoing and actual combat operations, merchant ships were converted and armed for escort work, while French ships were also fitted with ASDIC sets which enabled them to detect the presence of a submerged U Boat.

The massive expansion of ship building stretched British shipbuilding capacity – including its Canadian yards – to the limit. The building or completion of ships that would not be finished until after 1940 was scaled back or suspended in favour or ships that could be completed quickly, while the commissioning into the fleet of a series of four new aircraft carriers of the Illustrious class, ordered under an emergency review in 1936 and which were all finished or near completion, was delayed until later in the war in favour of more immediately useful vessels. Great efforts went into finishing the new battleships King George V and Prince of Wales before the Bismarck could be completed and begin attacking Allied convoys, while the French also strained to complete similarly advanced battleships, the Richelieu and the Jean Bart by the autumn of 1940 to meet the Mediterranean threat of two Italian battleships nearing completion.

To bridge the gap during the first crucial weeks while the auxiliary anti-submarine craft were prepared, aircraft carriers were used to escort the numerous unprotected craft approaching British shores. However this strategy proved costly; the new carrier Ark Royal was attacked by a U-boat on 14 September, and while it escaped, the old carrier Courageous was not so lucky, being sunk a few days later with heavy loss of life. Ships leaving port could be provided with a limited protective screen from aircraft flying from land bases, but at this stage of the conflict, a 'Mid-Atlantic Gap', where convoys could not be provided with air cover existed. Churchill lamented the loss of Berehaven and the other Southern Irish ports, greatly reducing the operational radius of the escorts, due to the determination of the Irish leader Éamon de Valera to remain resolutely neutral in the conflict.

In the first week of the war, Britain lost 65,000 tons of shipping; in the second week, 46,000 tons were lost, and in the third week 21,000 tons. By the end of September 1939, regular ocean convoys were in operation, outward from the Thames and Liverpool, and inwards from Gibraltar, Freetown and Halifax. To make up the losses of merchant vessels and to allow for increased imports of war goods, negotiations began with neutral countries such as Norway and the Netherlands towards taking over their freighters on central government charter.

Elsewhere, the blockade began to do its work. From Norway, across and down the North Sea, in the Channel and throughout the Mediterranean and Red Sea, Allied sea and air power began slowly to bleed away Germany's supplies. In the first 7 days of October alone, the British Contraband Control detained, either by confiscating neutral cargoes or capturing German ships, 13,800 tons of petrol, 2,500 tons of sulphur, 1,500 tons of jute (the raw material from which hessian and burlap cloth is made), 400 tons of textiles, 1,500 tons animal feed, 1,300 tons oils and fats, 1,200 tons of foodstuffs, 600 tons oilseeds, 570 tons copper, 430 tons of other ores and metals, 500 tons of phosphates, 320 tons of timber and various other quantities of chemicals, cotton, wool, hides and skins, rubber, silk, gums and resins, tanning material and ore crushing machinery.

Two months into the war, the Ministry reintroduced the "Navicert" (Navigational Certificate), first used to great effect during World War I. This system was in essence a commercial passport applied to goods before they were shipped, and was used on a wide scale. Possession of a Navicert proved that a consignment had already been passed as non-contraband by His Majesty's Ambassador in the country of origin and allowed the captain to pass Contraband Control patrols and ports without being stopped, sparing the navy and the Ministry the trouble of tracking the shipment. Violators, however, could expect harsh treatment. They could be threatened with Bunker Control measures, refused further certification or have their cargo or their vessel impounded. Conversely, neutrals who went out of their way to co-operate with the measures could expect "favoured nation" status, and have their ships given priority for approval. Italy, though an ally of Hitler, had not yet joined the war, and its captains enjoyed much faster turnarounds by following the Navicert system than the Americans, who largely refused to accept its legitimacy.

U.S. reaction to the British blockade

Passenger ships were also subject to Contraband Control because they carried luggage and small cargo items such as postal mail and parcels, and the Americans were particularly furious at the British insistence on opening all mail destined for Germany.[29] By 25 November 1939, 62 U.S. ships of various types had been stopped, some for as long as three weeks, and a lot of behind-the-scenes diplomacy took place to smooth over the political fallout[citation needed]. On 22 December the US State Department made a formal protest, to no avail. On 30 December the Manhattan, carrying 400 tons of small cargo, sailed from New York to deliver mail to Italy, but was stopped six days later by a British destroyer at Gibraltar. Although the captain went ashore to make a furious protest to the authorities with the American Consulate, the ship was delayed for 40 hours as British Contraband Control checked the records and ship's manifest, eventually removing 235 bags of mail addressed to Germany.[citation needed]

In the U.S., with its tradition that "the mail must always get through", and where armed robbery of the mail carried a mandatory 25-year jail term, there were calls for mail to be carried on warships, but the exercise – as with all such journeys – was repeated on the homeward leg as Contraband Control searched the ship again for anything of value that might have been taken out of Germany.[citation needed] On 22 January the UK ambassador was handed a note from the State Department calling the practice "wholly unwarrantable" and demanding immediate correction[citation needed]. But despite the British Foreign Office urging the Ministry of Economic Warfare to be cautious for fear of damaging relations with the US, the British claimed to have uncovered a nationwide US conspiracy to send clothing, jewels, securities, cash, foodstuffs, chocolate, coffee and soap to Germany through the post, and there was no climbdown.[citation needed]

Gruss und Kuss

From the war's beginning, a steady stream of packages, many marked Gruss und Kuss ("greetings and kisses!") had been sent from the United States through neutral countries to Germany by a number of US-based organisations, euphemistically termed "travel agencies", advertising special combinations of gift packages in German-language newspapers.[30] Despite high prices, one mail company, the Fortra Corporation of Manhattan admitted it had sent 30,000 food packages to Germany in less than three months, a business which exceeded US$1 million per year. The British said that, of 25,000 packages examined in three months, 17,000 contained contraband of food items as well as cash in all manner of foreign currency, diamonds, pearls, and maps of "potential military value". When a ton of air mail from the Pan American Airlines (PAA) flying boat American Clipper was confiscated in Bermuda, the American government banned outright the sending of parcels through the US airmail. During this period, the Italian Lati Airline, flying between South America and Europe was also used to smuggle[31] small articles such as diamonds and platinum, in some cases, concealed within the airframe, until the practice was ended by the Brazilian and US governments and the airline's assets in Brazil confiscated after the British intelligence services in the Americas engineered a breakdown in relations between the airline and the Brazilian government. The US travel agencies were eventually closed down along with the German consulates and information centres on 16 June 1941.[citation needed]

Phoney war

During the early months of the war – the Phoney War – the only place where there was substantial fighting was at sea.[4] News of the successes achieved by the men of Contraband Control were rarely out of the newspapers, and provided useful propaganda to shore up civilian morale. In the first 15 weeks of the war the Allies claimed to have taken 870,000 tons of goods, equal to 10% of Germany's normal imports for an entire year. This included 28 million US gallons (110,000 m3) of petrol and enough animal hides for 5 million pairs of boots, and did not take account of the loss to Germany from goods that had not been shipped at all for fear of seizure.

German preparations to counter the effects of the military and economic war were much more severe than in Britain. On 4 September a tax of 50% was placed on beer and tobacco, and income tax went up to 50%. For months previously, all able-bodied people in cities had by law to carry out war work such as filling sandbags for defenses and air-raid shelters, and it was now made an offense to ask for a raise in salary or to demand extra pay for overtime.[27] On 7 September wide-ranging new powers were granted to Heinrich Himmler to punish the populace for 'Endangering the defensive power of the German people'; the next day a worker was shot for refusing to take part in defensive work.[18] The new legislation, frequently enforced by the Peoples Court, was made deliberately vague to cover a variety of situations, and could be very severe. In time it would lead to the death penalty for such crimes as forging food coupons and protesting against the administration. Shirer recorded in his diary on 15 September that the blockade was already having a direct effect. It had cut Germany off from 50% of her normal imports of nickel, cotton, tin, oil and rubber, and since the war's beginning she had also lost access to French iron ore, making her extremely reliant on Sweden for this vital material.

Germany now looked to Romania for a large part of the oil she needed and to Soviet Union for a wide range of commodities. Apart from allowing Hitler to secure his eastern borders and annihilate Poland, the Nazi-Soviet Pact brought Germany considerable economic benefits in August 1939. As well as providing refueling and repair facilities for German U-boats and other vessels at its remote Arctic port of Teriberka, east of Murmansk, the Soviets – "Belligerent Neutrals" in Churchill's words – also accepted large quantities of wheat, tin, petrol and rubber from America into its ports in the Arctic and Black Sea and, rather than transport them over the entire continent, released identical volumes of the same material to Germany in the west. Before the war total US exports to Soviet Union were estimated as less than £1 million per month; by this stage, they were known to exceed £2 million per month. From the outset, although they had formerly been hated enemies, large-scale direct trade took place between the two countries because both were able to offer something the other wanted.[8] Germany lacked the natural resources Soviet Union had in abundance, whereas Soviet Union was at that time still a relatively backward country in want of the latest technology. However, by the end of December 1939 the Soviets didn't agree to start sending raw materiel since they weren't satisfied by German offers, citing refusal to get some of what they wanted and overly high prices on everyone else, and the actual trade within the framework treaty signed in August only took off in 1940 (see below).

The Germans maintained an aggressive strategy at sea in order to press home their own blockade of the Allies. Lloyd's List showed that by the end of 1939 they had sunk 249 ships by U-boat, air attack, or by mines. These losses included 112 British and 12 French vessels, but also demonstrated the disproportionate rate of loss by neutral nations. Norway, a great seafaring nation since the days of the Vikings had lost almost half its fleet in World War I, yet now possessed a merchant navy of some 2,000 ships, with tonnage exceeded only by Britain, the US, and Japan. They had already lost 23 ships, with many more attacked and dozens of sailors killed, while Sweden, Germany's main provider of iron ore, had lost 19 ships, Denmark 9, and Belgium 3. The Netherlands, with 75% of her commercial shipping outgoing from Rotterdam to Germany, had also lost 7 ships, yet all these countries continued to trade with Germany. Churchill was endlessly frustrated and bemused by the refusal of the neutrals to openly differentiate between the British and German methods of waging the sea war, and by their determination to maintain pre-war patterns of trade, but stopped short of condemning them, believing that events would eventually prove the Allies to be in the right. He commented;

At present their plight is lamentable and will become much worse. They bow humbly in fear of German threats of violence, each one hoping that if he feeds the crocodile enough the crocodile will eat him last and that the storm will pass before their turn comes to be devoured. What would happen if these neutrals, with one spontaneous impulse were to do their duty in accordance with the Covenant of the League and stand together with the British and French Empires against aggression and wrong?.

The neutral commerce which Churchill found most perplexing was the Swedish iron ore trade.[4] Sweden provided Germany with 9m tons of high grade ore per year via its Baltic ports, without which German armaments manufacture would be paralyzed. These ports froze in the winter, but an alternative route was available from the Norwegian port of Narvik from which the ore was transported down a partially hidden sea lane (which Churchill called the Norwegian Corridor) between the shoreline and the Skjaergaard (Skjærgård), a continuous chain of some 50,000 glacially formed skerries (small uninhabited islands), sea stacks and rocks running the entire 1,600 km length of the west coast. As in World War I, the Germans used the Norwegian Corridor to travel inside the 3-nautical-mile (5.6 km)-wide neutral waters where the Royal Navy and RAF were unable to attack them. Churchill considered this to be the "greatest impediment to the blockade", and continually pressed for the mining of the Skjaergaard to force the German ships to come out into the open seas where Contraband Control could deal with them, but the Norwegians, not wishing to antagonise the Germans, steadfastly refused to allow it.

Even so, by early October the Allies were growing increasingly confident at the effectiveness of their blockade and the apparent success of the recently introduced convoy system. A convoy of 15 freighters arrived in British ports unscathed from Canada bringing half a million bushels of wheat, while in France more important ships arrived from Halifax in another convoyed group. The French claimed that of 30 U-boats sent out in Germany's first major offensive against Allied shipping, a third had been destroyed, and Churchill declared that Britain had seized 150,000 more tons of contraband than was lost by torpedoing.[27] In mid-October Adolf Hitler called for fiercer action by his U-boat crews and the Luftwaffe to enforce his counter-blockade, and warned the Allies of his new "secret weapon". Neutral ships were warned against joining Allied convoys, Scandinavian merchants were ordered to use the Kiel Canal to facilitate the German's own Contraband Control and the US City of Flint, which had rescued survivors of the Athenia became the first American ship captured as prize of war by the Germans, although the episode proved farcical and the ship was eventually returned to its owners.

Minenkrieg

Hitler's "secret weapon" of the time was the magnetic mine.[4] The Germans had used mines against freighters from the beginning, but now began laying a new type, which did not need to make contact with a ship to destroy it, off the English coast, using seaplanes to drop them in British harbours, channels and estuaries too narrow or shallow for submarines to navigate. They ranged from small 200 lb (91 kg) mines dropped dozens at a time to large one-ton versions dropped by parachute on shoal bottoms which were almost impossible to sweep, equipped with magnetic triggers activated by a steel hull passing above. Over the next few days many ships of all sizes blew up in waters close to shore, mostly by explosions under or near the keels although the waters had been swept. Six went down in the mouth of the Thames, and the new cruiser Belfast was badly damaged at the mouth of the Firth of Forth.

The British urgently set to work to find a defence against the magnetic mine and began preparations to recreate the Northern Barrage, established between Scotland and Norway in 1917 as a safeguard against increasing U-boat attacks.[4] In his war speech to the Empire, Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain declared: "Already we know the secret of the magnetic mine and we shall soon master it as we have already mastered the U-boat", but shortly afterwards two more ships were sunk, bringing the week's total to 24. Evidence that at least part of Germany's attack was with illegal floating mines came when a British freighter was sunk at anchor off an east coast port, when two mines came together and exploded off Zeebrugge, and when a large whale was found near four German mines on the Belgian coast with a huge hole in its belly.[32] Over the weekend of 18–21 November six other neutral ships were sunk off the English coast, including a 12,000 ton Japanese liner.[27]

Eventually, a method of de-magnetising ships, known as degaussing was developed, which involved girding them in electric cable, and was quickly applied to all ships. Other means of minesweeping were also developed, whereby the mines were exploded by patrolling ships and aircraft fitted with a special fuse provocation apparatus.

Export ban

From early December 1939 the British began preventing German exports as a reprisal for the damage and loss of life caused by the German magnetic mines.[32] Chamberlain said that although he realised this would be detrimental to the neutrals, as Norway got nearly all its coal from Germany, the policy was in strict adherence to the rules of law, and that while Germany's use of mines and submarine warfare had already caused many innocent deaths regardless of nationality, no loss of life had been caused by the exercise of British sea power. Before the war, 70% of Germany's export trade was with European countries, mostly the Netherlands, France and England, but the Ministry estimated that Germany's remaining annual exports were worth £44m to South America, £19m to the Far East, £15m to the US, and that although nothing could be done to prevent the overland exports to Scandinavia, Italy, Russia and the Balkans, it was believed that German sea trade could be reduced by 45% by the measure.

Angry at the British export ban, the German Government accused the British of having deliberately sunk the Simon Bolivar, lost on 18 November with the loss of 120 people, including women and children. They advised neutrals to shun British waters and trade with Germany, declaring that because of the defensive minefields and contraband control, British waters were not mercantile fairways subject to the Hague Convention regulating sea warfare, but military areas where enemy ships of war must be attacked. Prompted by Germany, all the neutrals protested, but the overall effect was to slow the flow of neutral shipping to a standstill. The Nazi leadership later grew bullish at the apparent success of the mine strategy and admitted they were of German origin, stating that "our objectives are being achieved".

In Berlin, William Shirer recorded in his diary that there were signs of a rush to convert currency into goods to guard against inflation, but that although the blockade now meant that the German diet was very limited, there was generally enough to eat and people were at that point rarely going hungry. However, it was no longer possible to entertain at home unless the guests brought their own food and though restaurants and cafes still traded they were now very expensive and crowded.[32] Pork, veal and beef were rare, but in the early months there was still adequate venison, wild pig and wildfowl shot on estates and in forests. Coal was now very difficult to obtain however, and although sufficient crayfish were imported from the Danubian nations to allow an enjoyable festive meal, people went cold that Christmas. In fact, Germany produced large volumes of very high quality coal in the Saar region, but much of it was now being used to produce synthetic rubber, oil and gas. There were reports that Germany, which badly needed to raise foreign currency had been trying to export bicycles and cars to adjacent countries without tyres. The average German worker worked for 10 hours a day 6 days a week; but although he may have had enough money to buy them, most items were not available, and shops displayed goods in their windows accompanied by a sign saying 'Not For Sale'[18][33]

Such was the belief in the supreme strength of the Royal Navy that some thought that the blockade might now be so effective in restricting Germany's ability to fight that Hitler would be forced to come to the negotiation table.[34]

Meanwhile, at the beginning of 1940 there were still 60 German merchant ships alone in South American harbours, costing £300,000 per month in port and harbour dues, and Hitler eventually ordered them all to try to make a break for home. Up to the end of February 1940 about 70 had tried to get away, but very few reached Germany. Most were sunk or scuttled, and at least eight foundered on rocks trying to negotiate the way down the unfamiliar and hazardous Norwegian coast. The Germans tended to prefer to sink the ships themselves rather than allow the Allies to capture them, even at risk to those aboard. Such was the case of the Columbus, Germany's third-largest liner at 32,581 tons, and the Glucksburg, which ran herself ashore on the coast of Spain when sighted. Another, the "Watussi", was sighted off the Cape by the South African Air Force and the crew immediately set her on fire, trusting the aircrew to bring aid to the passengers and crew.

That winter was harsh, causing the Danube to freeze and heavy snow slowed rail transport, stalling Germany's grain and oil imports from Romania. The UK, having deprived Spain of her exports of iron ore to Germany entered into a deal to buy the ore instead via the Bay of Biscay, along with copper, mercury and lead to enable the Spanish, who were on the verge of famine, to raise the foreign exchange she needed to buy grain from South America to feed her people.

1940

On 17 January 1940 the Minister of Economic Warfare, Ronald Cross said in a speech in the House of Commons:

We have made a good start, we must bear in mind that Germany does not have the same resources she had some 25 years ago. Her resources in gold and foreign currency are smaller; her stocks of industrial raw materials are far smaller. At the end of four and a half months, Germany is in something like the same economic stress she was in after two years of the last war.[14]

Despite newsreels showing the effectiveness and power of the Nazi Blitzkrieg, which even her enemies believed, Germany was unable to afford a prolonged war. In order to buy from abroad without credit or foreign exchange (cash), a nation needed goods or gold to offer, but the British export ban prevented her from raising revenue. In World War I, even after two years of war Germany still had gold reserves worth 2.5m marks and over 30 billion marks invested abroad, giving her easy access to exports.[35] By this early stage of World War II, her gold reserves were down to around half a billion marks and her credit was almost nil, so any imports had to be paid for by barter, as with the high-technology equipment sent to Russia or coal to Italy.

In February 1940 Karl Ritter, who had brokered huge pre-war barter agreements with Brazil, visited Moscow and, despite finding Stalin an incredibly fierce negotiator, an increased trade deal was eventually signed between Germany and Russia. It was valued at 640 million Reichsmark in addition to that previously agreed, for which Germany would supply heavy naval guns, specimens of military land vehicles (e. g., a brand new Panzer III Ausf. E tank), thirty of their latest aircraft including the Messerschmitt Bf 109, Messerschmitt Bf 110 and Junkers Ju 88, locomotives, turbines, generators, the unfinished cruiser Lützow and the plans to the battleship Bismarck. In return Russia supplied in the first year one million tons of cereal, 1⁄2 million tons of wheat, 900,000 tons of oil, 100,000 tons of cotton, 1⁄2 million tons of phosphates, one million tons of soya beans and other goods. Although the Germans had been able to find numerous ways of beating the blockade, shortages were now so severe that on 30 March 1940, when he was gearing up for his renewed Blitzkrieg in the west, Hitler ordered that delivery of goods in payment to Russia should take priority even over those to his own armed forces. After the fall of France Hitler, intending to invade Russia the following year, declared that the trade need continue only until the spring of 1941, after which the Nazis intended to take all they needed.[8]

As more U-boats were commissioned into the German navy, the terrible toll on neutral merchant shipping intensified. After the first 6 months of the war, Norway had lost 49 ships with 327 men dead; Denmark 19 ships for 225 sailors killed and Sweden 32 ships for 243 men lost. In early March, Admiral Raeder was interviewed by an American correspondent from NBC regarding the alleged use of unrestrained submarine warfare. Raeder maintained that because the British blockade was illegal, the Germans were entitled to respond with "similar methods", and that because the British government had armed many of its merchant ships and used civilians to man coastal patrol vessels and minesweepers, any British ship sighted was considered a legitimate target. Raeder said that neutrals would only be liable to attack if they behaved as belligerents i.e. by zig-zagging or navigating without lights. The paradox with this argument – as the neutral countries were quick to point out – was that Germany was benefiting from the very same maritime activity they were trying so hard to destroy.

On 6 April, after the sinking of the Norwegian mail steamer Mira, the Norwegian Foreign Minister Professor Koht, referring to 21 protests made to belligerents about breaches to her neutrality, made a statement about the German sinking of Norwegian ships by U-boats and aircraft.[36] "We cannot understand how men of the German forces can find such a practice in accordance with their honour or humanitarian feelings". A few hours later another ship, the Navarra was torpedoed without warning, with the loss of 12 Norwegian seamen, by a U-boat which did not stop to pick up survivors.

Intensification of the blockade

Despite impressive statistics of the quantities of contraband captured, by the spring of 1940 the optimism of the British government over the success of the blockade appeared premature and a feeling developed that Germany was managing to maintain and even increase imports. Although the MEW tried to prevent it, neighbouring neutral countries continued to trade with Germany. In some cases, as with the crucial Swedish iron ore trade, it was done openly, but elsewhere, neutrals secretly acted as a conduit for supplies of materials that would otherwise be confiscated if sent directly to Germany.

A third of Dutchmen derived their livelihood from German trade, and Dutch traders were long suspected of acting as middle men in the supply of copper, tin, oil and industrial diamonds from America. Official figures showed that in the first 5 months of war, the Netherlands' imports of key materials from the US increased by £4.25m, but also Norway's purchases in the same area increased threefold to £3m a year, Sweden's by £5m and Switzerland's by £2m. Prominent in these purchases were cotton, petrol, iron, steel and copper – materials essential for waging war. While some increases may have been inflationary, some from a desire to build up their own armed forces or to stockpile reserves, it was exactly the type of activity the Ministry was trying to prevent.

American companies were prevented from openly supplying arms to belligerents by the Neutrality Acts, (an amendment was made on 21 September in the form of Cash and Carry) but no restrictions applied to raw materials. During the last 4 months of 1939, exports from the US to the 13 states capable of acting as middlemen to Germany amounted to £52m compared to £35m for the same period in 1938. By contrast, Britain and France spent £67m and £60m in the same periods respectively, and according to a writer in the New York World Telegram, exports to the 8 countries bordering Germany exceeded the loss of US exports previously sent directly to Germany.

But by far the biggest hole in the blockade was in the Balkans. Together Yugoslavia, Romania and Bulgaria annually exported to Germany a large part of their surplus oil, chromium, bauxite, pyrites, oil-bearing nuts, maize, wheat, meat and tobacco. Germany also made big purchases in Greece and Turkey and viewed the region as part of its supply hinterland. Before the war, Britain recognised Germany's special interest in the region and took a very small percentage of this market, but now, via the United Kingdom Commercial Corporation they used their financial power to compete in the Balkans, the Netherlands and Scandinavia, underselling and overbidding in markets to deprive Germany of goods, although Germany was so desperate to maintain supplies that they paid considerably over the normal market rate. As elsewhere, Germany paid in kind with military equipment, for which they were greatly aided with their acquisition of the Czech Skoda armaments interests.

Germany was almost entirely dependent on Hungary and Yugoslavia for bauxite, used in the production of Duralumin, a copper alloy of aluminium critical to aircraft production. The British attempted to stop the bauxite trade by sending undercover agents to blast the Iron Gate, the narrow gorge where the Danube cuts through the Carpathian Mountains by sailing a fleet of dynamite barges down the river, but the plan was prevented by Romanian police acting on a tip-off from the pro-German Iron Guard.[citation needed] Despite their declared neutrality, the politically unstable Balkan nations found themselves in an uncomfortable position, surrounded by Germany to the North, Italy to the West and Soviet Union to the East, with little room to refuse German veiled threats that, unless they continued to supply what was requested, they would suffer the same fate as Poland. Romania, which had made considerable territorial gains after World War I, exported a large proportion of the oil from its Ploiești site to Britain, its main guarantor of national sovereignty. Romania's production was about equal to that of Ohio, ranked 16th producer in the US, then a major oil-producing nation. The largest refinery, Astra Română, processed two million tons of petroleum a year but, as Britain's fortunes waned from the beginning of 1940, Romania turned to Germany using its oil as a bargaining tool, hoping for protection from the Soviet Union. On 29 May 1940 it stopped sending its oil to Britain, and signed an arms and oil pact with Germany; Romania was soon providing half her oil needs. Britain was able to arrange alternative supplies with the Anglo-Iranian Oil Agreement, signed on 28 August 1940.

The British Supreme War Council met in London on 28 March to discuss ways to intensify the blockade. According to The Economist,[when?] in April 1940 the war was costing the UK£5m per day out of total government expenditure of £6.5 – 7m per day. This was during the phoney war, before the fighting on land and air had begun. The Prime Minister said that, while it was out of the question to purchase all exportable surpluses, concentration on certain selected commodities such as minerals, fats and oil could have a useful effect, and announced a deal for Britain to acquire the entire export surplus of whale oil from Norway. Later Britain signed the Anglo-Swiss Trade Deal, and negotiations for war trade agreements were also concluded with Sweden, Norway, Iceland, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Denmark. Commercial agreements were negotiated with Spain, Turkey, and Greece, aimed at limiting material to Germany.

Chamberlain also indicated that steps were being taken to stop the Swedish iron ore trade, and a few days later the Norwegian coast was mined in Operation Wilfred. But perhaps the most important measure taken at this time was the setting up of the Special Operations Executive (SOE). SOE's origins go back to March 1939 following the German invasion of Czechoslovakia. It was set up by Lord Halifax with funding from the Secret Vote authorised by Prime Minister Chamberlain. In July 1940 Winston Churchill asked the Lord President (Neville Chamberlain) to define its structure and the document held at Kew CAB66/1 Extract 2 thereafter became known as the Charter of SOE. This Charter also defined the relationship of various organs of state including the security and police services with one another and initially the minister was the new Minister of Economic Warfare Hugh Dalton. Though very few people knew of it at the time, the new organisation, the earlier version of which carried out the attempt to dynamite the Iron Gate on the Danube, marked a new direction in the Economic War that would pay dividends later on, providing vital intelligence on potential strategic targets for the offensive bomber campaigns that came later in the war. There were turf wars from time to time with SIS who did not want to risk sources being compromised by SOE sabotage of enemy targets.

Bombing of Germany

Shortly after the German invasion of the Low Countries and France, the British took the first tentative steps towards the opening of a strategic air offensive aimed at carrying the fight to Germany. On 11 May 1940 the RAF bombed the city of Mönchengladbach.[37] On the night of 15/16 May 1940, RAF Bomber Command, which until that point had been used for little more than attacking coastal targets and dropping propaganda leaflets, set off on a night time raid on oil production and railway marshalling yards in the Ruhr district.

The mining and manufacturing region of the Ruhr, often likened to the Black Country in the Midlands of England, was one of the world's greatest concentrations of metal production and processing facilities as well as chemical and textile factories; the Ruhr was also home to several synthetic oil production plants. So much smog was produced by these industries that precision bombing was almost impossible.[citation needed] As Germany's most important industrial region, it had been equipped with strong air defenses – Hermann Göring had already declared, "The Ruhr will not be subjected to a single bomb. If an enemy bomber reaches the Ruhr, my name is not Hermann Göring!"[38] Because of the smog and the lack of aircraft fitted for aerial photography, the British were unable to determine how effective the raid had been; in fact the damage was negligible.[citation needed]

Second phase

Fall of France

The signing of the armistice with France in the Compiègne Forest on 24 June 1940 greatly changed the conditions of the Economic War. Hitler assumed control over the whole of Western Europe and Scandinavia (except for Sweden and Switzerland) from the north tip of Norway high above the Arctic Circle to the Pyrenees on the border with Spain, and from the River Bug in Poland to the English Channel. Germany established new airfields and U-boat bases all the way down the West Norwegian and European coasts.[8] On 30 June 1940 German occupation of the Channel Islands began. In early August Germans installed Dover Strait coastal guns.

From early July the German air force began attacking convoys in the English channel from its new bases and cross-channel guns shelled the Kentish coast in the opening stages of the Battle of Britain. On 17 August, following his inability to convince the British to make peace, Hitler announced a general blockade of the entire British Isles and gave the order to prepare for a full invasion of England codenamed Operation Sea Lion. On 1 August Italy, having joined the war, established a submarine base in Bordeaux. Its submarines were more suited to the Mediterranean, but they successfully ran the British gauntlet through the Straits of Gibraltar and joined the Atlantic blockade. On 20 August Benito Mussolini announced a blockade of all British ports in the Mediterranean, and over the next few months the region would experience a sharp increase in fighting.

Meanwhile, in Spain, which had still not recovered from her own civil war in which over one million died and which was in the grip of famine, General Francisco Franco continued to resist German attempts to persuade him to enter the war on the Axis side. Spain supplied Britain with iron ore from the Bay of Biscay, but, as a potential foe, she was a huge threat to British interests as she could easily restrict British naval access into the Mediterranean, either by shelling the Rock of Gibraltar or by allowing the Germans to lay siege to it from the mainland. Although Spain could gain the restoration of the rock itself and Catalonia under French administration, Franco could see Britain was far from defeated and that British forces backed by its huge powerful navy would occupy the Canary Islands. At this point Franco saw that the Royal Navy had reduced the German navy in Norway to an impotent surface threat, the Luftwaffe had lost the Battle of Britain, the Royal Navy had destroyed much of the French fleet at Mers-el-Kébir, had also destroyed Italian battleships at Taranto and the British Army was routing the Italian army in North & East Africa.[39] Franco continued to play for time. Franco made excessive demands of Hitler which he knew could not be satisfied as his personal price for participation, such as the ceding of most of Morocco and much of Algeria to Spain by France.[40] Operation Felix failed to materialise.

American opinion was shocked at the fall of France and the previous isolationist sentiment, which led to the Neutrality Acts from 1935 onwards, was slowly giving rise to a new realism. Roosevelt had already managed to negotiate an amendment to the acts on 21 September 1939, known as Cash and Carry, which though in theory maintained America's impartiality, blatantly favoured Britain and her Commonwealth. Under the new plan, weapons could now be bought by any belligerent providing they paid up front and took responsibility for delivery, but whereas Germany had virtually no foreign exchange and was unable to transport much material across the Atlantic, Britain had large reserves of gold and foreign currency, and while U-boats would be a threat, the likelihood was that her vast navy would ensure that the majority of equipment safely delivered to port.

The US now accepted that it needed to increase spending for its own defense, especially with the growing threat of Japan, but there was real concern that Britain would fall before the weapons were delivered.[15] Despite the success in evacuating a third of a million men at Dunkirk and the later evacuations from St Malo and St Nazaire, the British army left behind 2,500 heavy guns, 64,000 vehicles, 20,000 motor cycles and well over half a million tons of stores and ammunition. To help in the interim, Congress agreed to let Britain have a million[citation needed] mothballed First World War rifles, stored in grease with around fifty rounds of ammunition for each. But, following the British attack on the French fleet at Oran on 4 July to prevent it from falling into German hands, the British were proving they would do whatever was necessary to continue the fight, and Roosevelt was now winning his campaign to convince Congress to be even more supportive of Britain, with the Destroyers for Bases Agreement[40] and with the approval of a British order for 4,000 tanks.

Because of Germany's new proximity on the west European coastline and the decrease in shipping traffic, ships which would normally have been used for patrolling the high seas were diverted to more urgent tasks.[41] Britain discontinued its contraband control bases at Weymouth and The Downs and removed all but a skeleton staff from the control base at Kirkwall to continue searching the few ships bound for Sweden, Finland, Russia and her recently annexed Baltic satellites ( Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania surrendered on 21 June 1940 ).

The Navicert system was greatly extended, introducing compulsory Navicerts and ships' warrants in an attempt to prevent contraband being loaded in the first place.[41] Any consignment going to or from ports without a certificate of non-enemy origin and any ship without a ships Navicert became liable to seizure.

The lost Dutch and Danish supplies of meat and dairy products were replaced by sources in Ireland and New Zealand. Canada held a whole year's surplus of wheat, while the U.S. reserve was estimated to be the greatest in history, but Britain was suffering very heavy shipping losses as a result of expanding U-boat numbers. Virtually all Dutch and Belgian ships not captured by the Germans joined the British merchant fleet, which together with the tonnage contributed by Norway and Denmark added about one-third to Britain's merchant marine, giving them a large surplus of vessels. To prevent the enemy gaining a route to acquire supplies, the occupied countries and the unoccupied (Vichy) French zone immediately became subject to the blockade, with severe shortages and extreme hardship quickly following. Although the Ministry resisted calls that the embargo be extended to some neutral countries, it was later extended to cover the whole of metropolitan France, including Algeria, Tunisia and French Morocco.[42]

German gains

In course of the Battle of France, the Germans captured 2,000 tanks of various types, including the heavy French Char B1 and British Matildas, 5,000 artillery pieces, 300,000 rifles and at least 4 million rounds of ammunition. These were all available to be reconditioned, cannibalised or stripped down for scrap by the men of Organisation Todt. Despite attempts to transport it away before capture, occupied nations' gold reserves were also looted, along with huge numbers of artworks, many of which have never been recovered.

Occupied countries were subjected to relentless, systematic requisitioning of anything Germany required or desired.[43] This began with a vast physical looting, in which trains were requisitioned to carry to Germany all movable property such as captured weaponry, machinery, books, scientific instruments, art objects and furniture. As time went on other miscellaneous items such as clothing, soap, park benches, garden tools, bed linen and doorknobs were also taken. The looted goods were taken to Germany mainly by trains, which themselves were mostly kept by Germany.[44]

Immediate steps were also taken towards the appropriation of the best of the conquered nation's food. Decrees were proclaimed to force farmers to sell their animals and existing food stores, and while in the beginning a percentage of each year's crop was negotiated as part of the armistice terms, later the seizures became much more random and all-encompassing. Next, a blatantly unfair artificial exchange rate was announced (1 Reichsmark to 20 francs in France) and practically valueless "Invasion Marks" brought into circulation, quickly inflating and devaluing the local currency. Later, German agents bought non-portable assets such as farms, real estate, mines, factories and corporations. The individual central banks were forced to underwrite and finance German industrial schemes, insurance transactions, gold and foreign exchange transfers etc.

The Germans also gained the occupied country's natural resources and industrial capacity. In some cases these new resources were considerable, and were quickly reorganized for the Nazi war machine. The earlier acquisitions of Austria and Czechoslovakia yielded few natural resources apart from 4m annual tons of iron ore, a good proportion of Germany's need. Austria's iron and steel industry at Graz, and Czechoslovakia's heavy industry near Prague, which included the mighty Skoda munitions works at Pilsen were, though highly developed, as heavily reliant on imports of raw materials as Germany's. The conquest of Poland brought Germany half a million tons of oil per year and more zinc than it would ever need, and Luxembourg, though tiny, brought a well-organized iron and steel industry 1/7th as great as Germany's.

Norway provided good stocks of chromium, aluminum, copper, nickel and 1m annual pounds of molybdenum, the chemical element used in the production of high speed steels and as a substitute for tungsten. It also allowed them to continue to ship high quality Swedish iron ore from the port of Narvik, the trade which Britain tried to prevent with Operation Wilfred. In the Netherlands, they also acquired a large, high tech tin smelter in Arnhem, though the British, foreseeing the seizure, restricted the supply of raw tin leading up to the invasion, so the amount gained was only around a sixth of a year's supply (2,500 tons) for Germany.

But by far the biggest prize was France. German memories of the Versailles Treaty and of the turbulent years of reparations, food shortages and high inflation during the years immediately after World War I caused wealthy France to be treated as a vast material resource to be bled dry, and her entire economy was geared towards meeting Germany's needs. Under the armistice conditions she had to pay the billeting costs of the occupying garrison and a daily occupation indemnity of 300 to 400 million francs. The occupied zone contained France's best industries, with a fifth of the world's iron ore in Lorraine, and 6% of its steel production capacity. Germany's heavily overburdened railway network was reinforced with 4,000 French locomotives, and 300,000 (over half) of her freight cars.[45]

Unoccupied France ( Zone libre ) was left with only the rubber industries and textile factories around Lyon and its considerable reserves of bauxite, which because of the British blockade ended up in German hands anyway, giving her abundant supplies of aluminum for aircraft production. Along with the copper and tin she received from Russia, Yugoslav copper, Greek antimony and chromium and its Balkan sources, Germany now had sufficient supplies of most metals and coal. She also had around 2/3 of Europe's industrial capacity but lacked the necessary raw materials to feed the plants, many of them working at low capacity or closed[citation needed] because of RAF bombing, the general chaos and the flight of the populations.