A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Vietnamese | |

|---|---|

| tiếng Việt | |

| Pronunciation | [tiəŋ˧˦ viət̚˧˨ʔ] (Hà Nội) [tiəŋ˦˧˥ viək̚˨˩ʔ] (Huế) [tiəŋ˦˥ viək̚˨˩˨] ~ [tiəŋ˦˥ jiək̚˨˩˨] (Hồ Chí Minh City) |

| Native to | |

| Ethnicity | Vietnamese |

Native speakers | 85 million (2019)[1] |

Austroasiatic

| |

Early forms | |

| Latin (Vietnamese alphabet) Vietnamese Braille Chữ Nôm (historical) | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Regulated by | Vietnam Academy of Social Sciences |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | vi |

| ISO 639-2 | vie |

| ISO 639-3 | vie |

| Glottolog | viet1252 |

| Linguasphere | 46-EBA |

Areas within Vietnam with majority Vietnamese speakers, mirroring the ethnic landscape of Vietnam with ethnic Vietnamese dominating around the lowland pale of the country.[4] | |

Vietnamese (Vietnamese: tiếng Việt) is an Austroasiatic language spoken primarily in Vietnam where it is the national and official language. Vietnamese is spoken natively by around 85 million people,[1] several times as many as the rest of the Austroasiatic family combined.[5] It is the native language of the Vietnamese (Kinh) people, as well as a second or first language for other ethnic groups in Vietnam.

Like many languages in Southeast Asia and East Asia, Vietnamese is highly analytic and is tonal. It has head-initial directionality, with subject–verb–object order and modifiers following the words they modify. It also uses noun classifiers. Its vocabulary has had significant influence from Middle Chinese and loanwords from French.[6] Although is often mistakenly thought as being an monosyllabic language, Vietnamese words typically consist of from one to many as ten morphemes or syllables; the majority of Vietnamese vocabulary are disyllabic and trisyllabic words.[7]

Vietnamese is written using the Vietnamese alphabet (chữ Quốc ngữ). The alphabet is based on the Latin script and was officially adopted in the early 20th century during French rule of Vietnam. It uses digraphs and diacritics to mark tones and some phonemes. Vietnamese was historically written using chữ Nôm, a logographic script using Chinese characters (chữ Hán) to represent Sino-Vietnamese vocabulary and some native Vietnamese words, together with many locally invented characters to represent other words.[8][9]

Classification

Early linguistic work some 150 years ago (Logan 1852, Forbes 1881, Müller 1888, Kuhn 1889, Schmidt 1905, Przyluski 1924, and Benedict 1942)[10] classified Vietnamese as belonging to the Mon–Khmer branch of the Austroasiatic language family (which also includes the Khmer language spoken in Cambodia, as well as various smaller and/or regional languages, such as the Munda and Khasi languages spoken in eastern India, and others in Laos, southern China and parts of Thailand). Later, Mường was found to be more closely related to Vietnamese than other Mon–Khmer languages, and a Viet–Muong subgrouping was established, also including Thavung, Chut, Cuoi, etc.[11] The term "Vietic" was proposed by Hayes (1992),[12] who proposed to redefine Viet–Muong as referring to a subbranch of Vietic containing only Vietnamese and Mường. The term "Vietic" is used, among others, by Gérard Diffloth, with a slightly different proposal on subclassification, within which the term "Viet–Muong" refers to a lower subgrouping (within an eastern Vietic branch) consisting of Vietnamese dialects, Mường dialects, and Nguồn (of Quảng Bình Province).[13]

It has been proposed by Phan (2010, 2013) that Vietnamese is possibly a hybrid language which differs from a creole language. It is theorised that Vietnamese was descended from a proto-Austroasiatic language and was later hybridised by Middle Chinese. This hybridisation occurred due to a population of supposed Annamese Middle Chinese speakers living in the Red River Delta among Vietic speakers shifting from speaking Middle Chinese to speaking Proto-Viet–Muong.[14][15] This in turn, had an ad stratum effect where Proto-Viet-Muong borrowed a large amount of words from Annamese Middle Chinese forming an Old-Sino-Vietnamese substrate.[16] But ultimately Vietnamese is descended from Proto-Viet-Muong.

History

Vietnamese belongs to the Northern (Viet–Muong) clusters of the Vietic branch, spoken by the Vietic peoples, originating from Northern Vietnam. The language was first recorded in the Tháp Miếu Temple Inscription, dating from early 13th century AD.[17] The inscription was carved on a stone stele, in combined chữ Hán (Chinese characters used in the Vietnamese traditional writing system) and an archaic form of the chữ Nôm (writing system for vernacular Vietnamese language using Chinese characters).[18]

In the distant past, Vietnamese shared more characteristics common to other languages in Southeast Asia and with the Austroasiatic family, such as an inflectional morphology and a richer set of consonant clusters, which have subsequently disappeared from the language under Chinese influence.

Vietnamese is heavily influenced by its location in the Mainland Southeast Asia linguistic area, with the result that it has acquired or converged toward characteristics such as isolating morphology and phonemically distinctive tones, through processes of tonogenesis. These characteristics have become part of many of the genetically unrelated languages of Southeast Asia; for example, Tsat (a member of the Malayo-Polynesian group within Austronesian), and Vietnamese each developed tones as a phonemic feature. The ancestor of the Vietnamese language is usually believed to have been originally based in the area of the Red River Delta in what is now northern Vietnam.[19][20][21]

Distinctive tonal variations emerged during the subsequent expansion of the Vietnamese language and people from the Red River Plain into what is now central and southern Vietnam through conquest of the ancient nation of Champa and the Khmer people of the Mekong Delta in the vicinity of present-day Ho Chi Minh City, also known as Saigon.

Northern Vietnam was primarily influenced by Chinese, which came to predominate politically in the 2nd century BC whilst central and southern lands were occupied by Chamic and Khmer empires. After the emergence of the Ngô dynasty at the beginning of the 10th century, the ruling class adopted Classical Chinese as the formal medium of government, scholarship and literature. With the dominance of Chinese came radical importation of Chinese vocabulary and grammatical influence. The resulting Sino-Vietnamese vocabulary makes up about a third of the Vietnamese lexicon in all realms, and may account for as much as 60% of the vocabulary used in formal texts.[22]

After France invaded Vietnam in the late 19th century, French gradually replaced Literary Chinese as the official language in education and government. Vietnamese adopted many French terms, such as đầm ('dame', from madame), ga ('train station', from gare), sơ mi ('shirt', from chemise), and búp bê ('doll', from poupée), resulting in a language that was Austroasiatic but with major Sino-influences and some minor French influences from the French colonial era.

French sinologist, Henri Maspero, described six periods of the Vietnamese language:[23][24]

- Proto-Viet–Muong, also known as Pre-Vietnamese, the ancestor of Vietnamese and the related Mường language (before 7th century AD).

- Proto-Vietnamese, the oldest reconstructable version of Vietnamese, dated to just before the entry of massive amounts of Sino-Vietnamese vocabulary into the language, c. 7th to 9th century AD. At this state, the language had three tones.

- Archaic Vietnamese, the state of the language upon adoption of the Sino-Vietnamese vocabulary and the beginning of creation of the Vietnamese characters (chữ Nôm) during the Ngô Dynasty, c. 10th century AD.

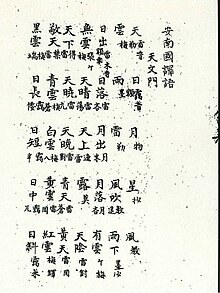

- Ancient Vietnamese, the language represented by chữ Nôm (c. 15th century), widely used during the Lê dynasty. The Ming glossary "Annanguo Yiyu" 安南國譯語 (c. 15th century) by the Bureau of Interpreters 會同館 (from the series Huáyí Yìyǔ (Chinese: 華夷譯語) recorded the language at this point of history. The Bureau of Interpreters used Chinese approximations to record Vietnamese rather than use Sino-Vietnamese to record as has been done in Annan Yiyu 安南譯語, a prior work.[25] By this point, a tone split had happened in the language, leading to six tones but a loss of contrastive voicing among consonants.

- Middle Vietnamese, the language found in Dictionarium Annamiticum Lusitanum et Latinum of the Jesuit missionary Alexandre de Rhodes (c. 17th century); the dictionary was published in Rome in 1651. Another famous dictionary of this period was written by P. J. Pigneau de Behaine in 1773 and published by Jean-Louis Taberd in 1838.

- Modern Vietnamese, from the 19th century.

Proto–Viet–Muong

The following diagram shows the phonology of Proto–Viet–Muong (the nearest ancestor of Vietnamese and the closely related Mường language), along with the outcomes in the modern language:[26][27][28][29]

Labial Dental/Alveolar Palatal Velar Glottal Nasal *m > m *n > n *ɲ > nh *ŋ > ng/ngh Stop tenuis *p > b *t > đ *c > ch *k > k/c/q *ʔ > # voiced *b > b *d > đ *ɟ > ch *ɡ > k/c/q aspirated *pʰ > ph *tʰ > th *kʰ > kh implosive *ɓ > m *ɗ > n *ʄ > nh 1 Affricate *tʃ > x 1 Fricative voiceless *s > t *h > h voiced 2 *(β) > v 3 *(ð) > d *(r̝) > r 4 *(ʝ) > gi *(ɣ) > g/gh Approximant *w > v *l > l *r > r *j > d

^1 According to Ferlus, */tʃ/ and */ʄ/ are not accepted by all researchers. Ferlus 1992[26] also had additional phonemes */dʒ/ and */ɕ/.

^2 The fricatives indicated above in parentheses developed as allophones of stop consonants occurring between vowels (i.e. when a minor syllable occurred). These fricatives were not present in Proto-Viet–Muong, as indicated by their absence in Mường, but were evidently present in the later Proto-Vietnamese stage. Subsequent loss of the minor-syllable prefixes phonemicized the fricatives. Ferlus 1992[26] proposes that originally there were both voiced and voiceless fricatives, corresponding to original voiced or voiceless stops, but Ferlus 2009[27] appears to have abandoned that hypothesis, suggesting that stops were softened and voiced at approximately the same time, according to the following pattern:

- *p, *b > /β/

- *t, *d > /ð/

- *s > /r̝/

- *c, *ɟ, *tʃ > /ʝ/

- *k, *ɡ > /ɣ/

^3 In Middle Vietnamese, the outcome of these sounds was written with a hooked b (ꞗ), representing a /β/ that was still distinct from v (then pronounced ?pojem=). See below.

^4 It is unclear what this sound was. According to Ferlus 1992,[26] in the Archaic Vietnamese period (c. 10th century AD, when Sino-Vietnamese vocabulary was borrowed) it was *r̝, distinct at that time from *r.

The following initial clusters occurred, with outcomes indicated:

- *pr, *br, *tr, *dr, *kr, *gr > /kʰr/ > /kʂ/ > s

- *pl, *bl > MV bl > Northern gi, Southern tr

- *kl, *gl > MV tl > tr

- *ml > MV ml > mnh > nh

- *kj > gi

A large number of words were borrowed from Middle Chinese, forming part of the Sino-Vietnamese vocabulary. These caused the original introduction of the retroflex sounds /ʂ/ and /ʈ/ (modern s, tr) into the language.

Origin of tones

Proto-Viet–Muong had no tones to speak of. The tones later developed in some of the daughter languages from distinctions in the initial and final consonants. Vietnamese tones developed as follows:[30]

Register Initial consonant Smooth ending Glottal ending Fricative ending High (first) register Voiceless A1 ngang "level" B1 sắc "sharp" C1 hỏi "asking" Low (second) register Voiced A2 huyền "deep" B2 nặng "heavy" C2 ngã "tumbling"

Glottal-ending syllables ended with a glottal stop /ʔ/, while fricative-ending syllables ended with /s/ or /h/. Both types of syllables could co-occur with a resonant (e.g. /m/ or /n/).

At some point, a tone split occurred, as in many other mainland Southeast Asian languages. Essentially, an allophonic distinction developed in the tones, whereby the tones in syllables with voiced initials were pronounced differently from those with voiceless initials. (Approximately speaking, the voiced allotones were pronounced with additional breathy voice or creaky voice and with lowered pitch. The quality difference predominates in today's northern varieties, e.g. in Hanoi, while in the southern varieties the pitch difference predominates, as in Ho Chi Minh City.) Subsequent to this, the plain-voiced stops became voiceless and the allotones became new phonemic tones. The implosive stops were unaffected, and in fact developed tonally as if they were unvoiced. (This behavior is common to all East Asian languages with implosive stops.)

As noted above, Proto-Viet–Muong had sesquisyllabic words with an initial minor syllable (in addition to, and independent of, initial clusters in the main syllable). When a minor syllable occurred, the main syllable's initial consonant was intervocalic and as a result suffered lenition, becoming a voiced fricative. The minor syllables were eventually lost, but not until the tone split had occurred. As a result, words in modern Vietnamese with voiced fricatives occur in all six tones, and the tonal register reflects the voicing of the minor-syllable prefix and not the voicing of the main-syllable stop in Proto-Viet–Muong that produced the fricative. For similar reasons, words beginning with /l/ and /ŋ/ occur in both registers. (Thompson 1976[29] reconstructed voiceless resonants to account for outcomes where resonants occur with a first-register tone, but this is no longer considered necessary, at least by Ferlus.)