A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Policy of | European Union |

|---|---|

| Type | Monetary union |

| Currency | Euro |

| Established | 1 January 1999 |

| Members | |

| Governance | |

| Monetary authority | Eurosystem |

| Political oversight | Eurogroup |

| Statistics | |

| Area | 2,801,552 km2 (1,081,685 sq mi)[1] |

| Population | 349,616,346 (January 1st 2023)[2] |

| Density | 125/km2 (323.7/sq mi) |

| GDP (nominal) | €14.372 trillion €40,990 (per capita) (2023)[3] |

| Interest rate | 4.00%[4] |

| Inflation | 2.4% (March 2024)[5] |

| Unemployment | 6.5% (February 2024)[6] |

| Trade balance | €310 billion trade surplus[7] |

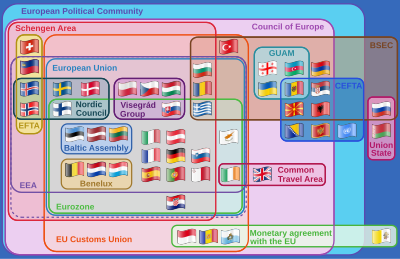

The euro area,[8] commonly called the eurozone (EZ), is a currency union of 20 member states of the European Union (EU) that have adopted the euro (€) as their primary currency and sole legal tender, and have thus fully implemented EMU policies.

The 20 eurozone members are:

- Austria, Belgium, Croatia, Cyprus, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, and Spain.

The seven non-eurozone members of the EU are Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Hungary, Poland, Romania, and Sweden. They continue to use their own national currencies, although all but Denmark are obliged to join once they meet the euro convergence criteria.[9]

Among non-EU member states, Andorra, Monaco, San Marino, and Vatican City have formal agreements with the EU to use the euro as their official currency and issue their own coins.[10][11][12] In addition, Kosovo and Montenegro have adopted the euro unilaterally, relying on euros already in circulation rather than minting currencies of their own.[13] These six countries, however, have no representation in any eurozone institution.[14]

The Eurosystem is the monetary authority of the eurozone, the Eurogroup is an informal body of finance ministers that makes fiscal policy for the currency union, and the European System of Central Banks is responsible for fiscal and monetary cooperation between eurozone and non-eurozone EU members. The European Central Bank (ECB) makes monetary policy for the eurozone, sets its base interest rate, and issues euro banknotes and coins.

Since the financial crisis of 2007–2008, the eurozone has established and used provisions for granting emergency loans to member states in return for enacting economic reforms.[citation needed] The eurozone has also enacted some limited fiscal integration; for example, in peer review of each other's national budgets. The issue is political and in a state of flux in terms of what further provisions will be agreed for eurozone change. No eurozone member state has left, and there are no provisions to do so or to be expelled.[15]

Territory

Eurozone

In 1998, eleven member states of the European Union had met the euro convergence criteria, and the eurozone came into existence with the official launch of the euro (alongside national currencies) on 1 January 1999 in those countries: Austria, Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal, and Spain. Greece qualified in 2000 and was admitted on 1 January 2001.

These twelve founding members introduced physical euro banknotes and euro coins on 1 January 2002. After a short transition period, they took out of circulation and rendered invalid their pre-euro national coins and notes.

Between 2007 and 2023, eight new states have acceded: Croatia, Cyprus, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Slovakia, and Slovenia.

| state | ISO code | adopted on 1 January of | population in 2021[2] | nominal GNI in 2021 in millions of USD[16] | nominal GNI as fraction of eurozone total | nominal GNI per capita in 2021 in USD | pre-euro currency | conversion rate of euro to pre-euro currency[17] | pre-euro currency was also used in | territories where euro is not used |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AT | 1999[18] | 8,932,664 | 472,474 | 3.27% | 52,893 | schilling | 13.7603 | |||

| BE | 1999[18] | 11,554,767 | 585,375 | 4.05% | 50,661 | franc | 40.3399 | Luxembourg | ||

| HR | 2023[19] | 4,036,355 | 68,724 | 0.48% | 17,026 | kuna | 7.53450 | |||

| CY | 2008[20] | 896,007 | 25,634 | 0.18% | 28,609 | pound | 0.585274 | Northern Cyprus[a] | ||

| EE | 2011[21] | 1,330,068 | 35,219 | 0.24% | 26,479 | kroon | 15.6466 | |||

| FI | 1999[18] | 5,533,793 | 296,473 | 2.05% | 53,575 | markka | 5.94573 | |||

| FR | 1999[18] | 67,656,682 | 2,991,553 | 20.69% | 44,217 | franc | 6.55957 | Andorra Monaco |

New Caledonia[b] French Polynesia[b] Wallis and Futuna[b] | |

| DE | 1999[18] | 83,155,031 | 4,298,325 | 29.72% | 51,690 | Mark | 1.95583 | Kosovo Montenegro |

||

| GR[c] | 2001[22] | 10,678,632 | 212,807 | 1.47% | 19,928 | drachma | 340.750 | |||

| IE | 1999[18] | 5,006,324 | 383,084 | 2.65% | 76,520 | pound | 0.787564 | |||

| IT | 1999[18] | 59,236,213 | 2,127,119 | 14.71% | 35,909 | lira | 1936.27 | San Marino Vatican City |

||

| LV | 2014[23] | 1,893,223 | 37,295 | 0.26% | 19,699 | lats | 0.702804 | |||

| LT | 2015[24] | 2,795,680 | 60,884 | 0.42% | 21,778 | litas | 3.45280 | |||

| LU | 1999[18] | 634,730 | 56,449 | 0.39% | 88,934 | franc | 40.3399 | Belgium | ||

| MT | 2008[25] | 516,100 | 15,948 | 0.11% | 30,901 | lira | 0.429300 | |||

| NL | 1999[18] | 17,475,415 | 967,837 | 6.69% | 55,383 | guilder | 2.20371 | Aruba[d] Curaçao[e] Sint Maarten[e] Caribbean Netherlands[f] | ||

| PT | 1999[18] | 10,298,252 | 246,714 | 1.71% | 23,957 | escudo | 200.482 | |||

| SK | 2009[26] | 5,459,781 | 112,424 | 0.78% | 20,591 | koruna | 30.1260 | |||

| SI | 2007[27] | 2,108,977 | 59,608 | 0.41% | 28,264 | tolar | 239.640 | |||

| ES | 1999[18] | 47,398,695 | 1,407,936 | 9.74% | 29,704 | peseta | 166.386 | Andorra | ||

| eurozone | EZ[g] | — | 346,597,389[h] | 14,461,883 | 100.00% | 41,725 | — | — | — | see above |

Dependent territories of EU member states not part of the EU

Three French dependent territories that are not part of the EU have adopted the euro, with France ensuring eurozone laws are implemented:

- Territorial collectivity of Saint Barthélemy

- Overseas Collectivity of Saint-Pierre and Miquelon

- French Southern and Antarctic Lands

Non-member usage

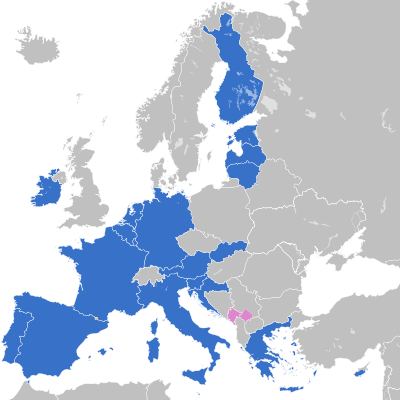

- European Union member states (special territories not shown)

- 20 in the eurozone1 in ERM II, with an opt-out (Denmark)5 not in ERM II, but obliged to join the eurozone on meeting the convergence criteria (Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Romania, and Sweden)

- Non–EU member states

With formal agreement

The euro is also used in countries outside the EU. Four states (Andorra, Monaco, San Marino, and Vatican City) have signed formal agreements with the EU to use the euro and issue their own coins.[28][29] Nevertheless, they are not considered part of the eurozone by the ECB and do not have a seat in the ECB or Euro Group.

Akrotiri and Dhekelia (located on the island of Cyprus) belong to the United Kingdom, but there are agreements between the UK and Cyprus[citation needed] and between UK and EU[citation needed] about their partial integration with Cyprus and partial adoption of Cypriot law, including the usage of euro in Akrotiri and Dhekelia.[citation needed]

Several currencies are pegged to the euro, some of them with a fluctuation band and others with an exact rate. The Bosnia and Herzegovina convertible mark was once pegged to the Deutsche mark at par, and continues to be pegged to the euro today at the Deutsche mark's old rate (1.95583 per euro). The Bulgarian lev was initially pegged to the Deutsche Mark at a rate of BGL 1000 to DEM 1 in 1997, and has been pegged at a rate of BGN 1.95583 to EUR 1 since the introduction of the euro and the redenomination of the lev in 1999. The West African and Central African CFA francs are pegged exactly at 655.957 CFA to 1 EUR. In 1998, in anticipation of Economic and Monetary Union of the European Union, the Council of the European Union addressed the monetary agreements France had with the CFA Zone and Comoros, and ruled that the ECB had no obligation towards the convertibility of the CFA and Comorian francs. The responsibility of the free convertibility remained in the French Treasury.

Without formal agreement

Kosovo and Montenegro unilaterally adopted the euro as their sole currency without an agreement and, therefore, have no issuing rights.[29] These states are not considered part of the eurozone by the ECB. However, sometimes the term eurozone is applied to all territories that have adopted the euro as their sole currency.[30][31][32] Further unilateral adoption of the euro (euroisation), by both non-euro EU and non-EU members, is opposed by the ECB and EU.[33]

Historical eurozone enlargements and exchange-rate regimes for EU members

The chart below provides a full summary of all applying exchange-rate regimes for EU members, since the birth, on 13 March 1979, of the European Monetary System with its Exchange Rate Mechanism and the related new common currency ECU. On 1 January 1999, the euro replaced the ECU 1:1 at the exchange rate markets. During 1979–1999, the Deutsche Mark functioned as a de facto anchor for the ECU, meaning there was only a minor difference between pegging a currency against the ECU and pegging it against the Deutsche Mark.

Sources: EC convergence reports 1996-2014, Italian lira, Spanish peseta, Portuguese escudo, Finnish markka, Greek drachma, Sterling

The eurozone was born with its first 11 member states on 1 January 1999. The first enlargement of the eurozone, to Greece, took place on 1 January 2001, one year before the euro physically entered into circulation. The next enlargements were to states which joined the EU in 2004, and then joined the eurozone on 1 January of the year noted: Slovenia in 2007, Cyprus in 2008, Malta in 2008, Slovakia in 2009, Estonia in 2011, Latvia in 2014, and Lithuania in 2015. Croatia, which acceded to the EU in 2013, adopted the euro in 2023.

All new EU members joining the bloc after the signing of the Maastricht Treaty in 1992 are obliged to adopt the euro under the terms of their accession treaties. However, the last of the five economic convergence criteria which need first to be complied with in order to qualify for euro adoption, is the exchange rate stability criterion, which requires having been an ERM-member for a minimum of two years without the presence of "severe tensions" for the currency exchange rate.

In September 2011, a diplomatic source close to the euro adoption preparation talks with the seven remaining new member states who had yet to adopt the euro at that time (Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, and Romania), claimed that the monetary union (eurozone) they had thought they were going to join upon their signing of the accession treaty may very well end up being a very different union, entailing a much closer fiscal, economic, and political convergence than originally anticipated. This changed legal status of the eurozone could potentially cause them to conclude that the conditions for their promise to join were no longer valid, which "could force them to stage new referendums" on euro adoption.[34]

Future enlargement

Seven countries (Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Hungary, Poland, Romania, and Sweden) are EU members but do not use the euro.

Before joining the eurozone, a state must spend at least two years in the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM II). As of January 2023[update], the Danish central bank and the Bulgarian central bank participate in ERM II.

Denmark obtained a special opt-out in the original Maastricht Treaty, and thus is legally exempt from joining the eurozone unless its government decides otherwise, either by parliamentary vote or referendum. The United Kingdom likewise had an opt-out prior to withdrawing from the EU in 2020.

The remaining six countries are obliged to adopt the euro in future, although the EU has so far not tried to enforce any time plan. They should join as soon as they fulfill the convergence criteria, which include being part of ERM II for two years. Sweden, which joined the EU in 1995 after the Maastricht Treaty was signed, is required to join the eurozone. However, the Swedish people turned down euro adoption in a 2003 referendum and since then the country has intentionally avoided fulfilling the adoption requirements by not joining ERM II, which is voluntary.[35][36] Bulgaria joined ERM II on 10 July 2020.[37]

Interest in joining the eurozone increased in Denmark, and initially in Poland, as a result of the financial crisis of 2007–2008. In Iceland, there was an increase in interest in joining the European Union, a pre-condition for adopting the euro.[38] However, by 2010 the debt crisis in the eurozone caused interest from Poland, as well as the Czech Republic, Denmark and Sweden to cool.[39]

Expulsion and withdrawal

In the opinion of journalist Leigh Phillips and Locke Lord's Charles Proctor,[40][41] there is no provision in any European Union treaty for an exit from the eurozone. In fact, they argued, the Treaties make it clear that the process of monetary union was intended to be "irreversible" and "irrevocable".[41] However, in 2009, a European Central Bank legal study argued that, while voluntary withdrawal is legally not possible, expulsion remains "conceivable".[42] Although an explicit provision for an exit option does not exist, many experts and politicians in Europe have suggested an option to leave the eurozone should be included in the relevant treaties.[43]

On the issue of leaving the eurozone, the European Commission has stated that "he irrevocability of membership in the euro area is an integral part of the Treaty framework and the Commission, as a guardian of the EU Treaties, intends to fully respect ."[44] It added that it "does not intend to propose amendment" to the relevant Treaties, the current status being "the best way going forward to increase the resilience of euro area Member States to potential economic and financial crises.[44] The European Central Bank, responding to a question by a Member of the European Parliament, has stated that an exit is not allowed under the Treaties.[45]

Likewise there is no provision for a state to be expelled from the euro.[46] Some, however, including the Dutch government, favour the creation of an expulsion provision for the case whereby a heavily indebted state in the eurozone refuses to comply with an EU economic reform policy.[47]

In a Texas law journal, University of Texas at Austin law professor Jens Dammann has argued that even now EU law contains an implicit right for member states to leave the eurozone if they no longer meet the criteria that they had to meet in order to join it.[48] Furthermore, he has suggested that, under narrow circumstances, the European Union can expel member states from the eurozone.[49]

Administration and representation

The monetary policy of all countries in the eurozone is managed by the European Central Bank (ECB) and the Eurosystem which comprises the ECB and the central banks of the EU states who have joined the eurozone. Countries outside the eurozone are not represented in these institutions. Whereas all EU member states are part of the European System of Central Banks (ESCB), non EU member states have no say in all three institutions, even those with monetary agreements such as Monaco. The ECB is entitled to authorise the design and printing of euro banknotes and the volume of euro coins minted, and its president is currently Christine Lagarde.

The eurozone is represented politically by its finance ministers, known collectively as the Eurogroup, and is presided over by a president, currently Paschal Donohoe. The finance ministers of the EU member states that use the euro meet a day before a meeting of the Economic and Financial Affairs Council (Ecofin) of the Council of the European Union. The Group is not an official Council formation but when the full EcoFin council votes on matters only affecting the eurozone, only Euro Group members are permitted to vote on it.[50][51][52]

Since the global financial crisis of 2007–2008, the Euro Group has met irregularly not as finance ministers, but as heads of state and government (like the European Council). It is in this forum, the Euro summit, that many eurozone reforms have been decided upon. In 2011, former French President Nicolas Sarkozy pushed for these summits to become regular and twice a year in order for it to be a 'true economic government'.[citation needed]

Reform

In April 2008 in Brussels, future European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker suggested that the eurozone should be represented at the IMF as a bloc, rather than each member state separately: "It is absurd for those 15 countries not to agree to have a single representation at the IMF. It makes us look absolutely ridiculous. We are regarded as buffoons on the international scene".[53] In 2017 Juncker stated that he aims to have this agreed by the end of his mandate in 2019.[54] However, Finance Commissioner Joaquín Almunia stated that before there is common representation, a common political agenda should be agreed upon.[53]

Leading EU figures including the commission and national governments have proposed a variety of reforms to the eurozone's architecture; notably the creation of a Finance Minister, a larger eurozone budget, and reform of the current bailout mechanisms into either a "European Monetary Fund" or a eurozone Treasury. While many have similar themes, details vary greatly.[55][56][57][58]

Economy

Comparison table

| Population (2023) | GDP (Local currency) (2023) | GDP (US$) (2023) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1410 million | CNY 126.1 trillion | US$ 17.7 trillion | |

| 349 million | EUR 14.4 trillion | US$ 15.6 trillion | |

| 335 million | USD 26.9 trillion | US$ 26.9 trillion |

| Economy | Nominal GDP (billions in USD) – Peak year as of 2020

|

|---|---|

| (01) United States (Peak in 2019) | 21,439

|

| (02) China (Peak in 2020) | 14,860

|

| (03) Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Analytika

Antropológia Aplikované vedy Bibliometria Dejiny vedy Encyklopédie Filozofia vedy Forenzné vedy Humanitné vedy Knižničná veda Kryogenika Kryptológia Kulturológia Literárna veda Medzidisciplinárne oblasti Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy Metavedy Metodika Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok. www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk |