A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Part of a series on |

| Finance |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Macroeconomics |

|---|

|

An interest rate is the amount of interest due per period, as a proportion of the amount lent, deposited, or borrowed (called the principal sum). The total interest on an amount lent or borrowed depends on the principal sum, the interest rate, the compounding frequency, and the length of time over which it is lent, deposited, or borrowed.

The annual interest rate is the rate over a period of one year. Other interest rates apply over different periods, such as a month or a day, but they are usually annualized.

The interest rate has been characterized as "an index of the preference . . . for a dollar of present over a dollar of future income."[1] The borrower wants, or needs, to have money sooner, and is willing to pay a fee—the interest rate—for that privilege.

Influencing factors

Interest rates vary according to:

- the government's directives to the central bank to accomplish the government's goals

- the currency of the principal sum lent or borrowed

- the term to maturity of the investment

- the perceived default probability of the borrower

- supply and demand in the market

- the amount of collateral

- special features like call provisions

- reserve requirements

- compensating balance

as well as other factors.

Example

A company borrows capital from a bank to buy assets for its business. In return, the bank charges the company interest. (The lender might also require rights over the new assets as collateral.)

A bank will use the capital deposited by individuals to make loans to their clients. In return, the bank should pay interest to individuals who have deposited their capital. The amount of interest payment depends on the interest rate and the amount of capital they deposited.

Related terms

Base rate usually refers to the annualized effective interest rate offered on overnight deposits by the central bank or other monetary authority.[citation needed]

The annual percentage rate (APR) may refer either to a nominal APR or an effective APR (EAPR). The difference between the two is that the EAPR accounts for fees and compounding, while the nominal APR does not.

The annual equivalent rate (AER), also called the effective annual rate, is used to help consumers compare products with different compounding frequencies on a common basis, but does not account for fees.

A discount rate[2] is applied to calculate present value.

For an interest-bearing security, coupon rate is the ratio of the annual coupon amount (the coupon paid per year) per unit of par value, whereas current yield is the ratio of the annual coupon divided by its current market price. Yield to maturity is a bond's expected internal rate of return, assuming it will be held to maturity, that is, the discount rate which equates all remaining cash flows to the investor (all remaining coupons and repayment of the par value at maturity) with the current market price.

Based on the banking business, there are deposit interest rate and loan interest rate.

Based on the relationship between supply and demand of market interest rate, there are fixed interest rate and floating interest rate.

Monetary policy

Interest rate targets are a vital tool of monetary policy and are taken into account when dealing with variables like investment, inflation, and unemployment. The central banks of countries generally tend to reduce interest rates when they wish to increase investment and consumption in the country's economy. However, a low interest rate as a macro-economic policy can be risky and may lead to the creation of an economic bubble, in which large amounts of investments are poured into the real-estate market and stock market. In developed economies, interest-rate adjustments are thus made to keep inflation within a target range for the health of economic activities or cap the interest rate concurrently with economic growth to safeguard economic momentum.[3][4][5][6][7]

History

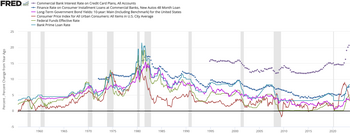

In the past two centuries, interest rates have been variously set either by national governments or central banks. For example, the Federal Reserve federal funds rate in the United States has varied between about 0.25% and 19% from 1954 to 2008, while the Bank of England base rate varied between 0.5% and 15% from 1989 to 2009,[8][9] and Germany experienced rates close to 90% in the 1920s down to about 2% in the 2000s.[10][11] During an attempt to tackle spiraling hyperinflation in 2007, the Central Bank of Zimbabwe increased interest rates for borrowing to 800%.[12]

The interest rates on prime credits in the late 1970s and early 1980s were far higher than had been recorded – higher than previous US peaks since 1800, than British peaks since 1700, or than Dutch peaks since 1600; "since modern capital markets came into existence, there have never been such high long-term rates" as in this period.[13]

Possibly before modern capital markets, there have been some accounts that savings deposits could achieve an annual return of at least 25% and up to as high as 50%. (William Ellis and Richard Dawes, "Lessons on the Phenomenon of Industrial Life... ", 1857, p III–IV)

Reasons for changes

- Political short-term gain: Lowering interest rates can give the economy a short-run boost. Under normal conditions, most economists think a cut in interest rates will only give a short term gain in economic activity that will soon be offset by inflation. The quick boost can influence elections. Most economists advocate independent central banks to limit the influence of politics on interest rates.

- Deferred consumption: When money is loaned the lender delays spending the money on consumption goods. Since according to time preference theory people prefer goods now to goods later, in a free market there will be a positive interest rate.

- Inflationary expectations: Most economies generally exhibit inflation, meaning a given amount of money buys fewer goods in the future than it will now. The borrower needs to compensate the lender for this.

- Alternative investments: The lender has a choice between using his money in different investments. If he chooses one, he forgoes the returns from all the others. Different investments effectively compete for funds.

- Risks of investment: There is always a risk that the borrower will go bankrupt, abscond, die, or otherwise default on the loan. This means that a lender generally charges a risk premium to ensure that, across his investments, he is compensated for those that fail.

- Liquidity preference: People prefer to have their resources available in a form that can immediately be exchanged, rather than a form that takes time to realize.

- Taxes: Because some of the gains from interest may be subject to taxes, the lender may insist on a higher rate to make up for this loss.

- Banks: Banks can tend to change the interest rate to either slow down or speed up economy growth. This involves either raising interest rates to slow the economy down, or lowering interest rates to promote economic growth.[14]

- Economy: Interest rates can fluctuate according to the status of the economy. It will generally be found that if the economy is strong then the interest rates will be high, if the economy is weak the interest rates will be low.

Real versus nominal

The nominal interest rate is the rate of interest with no adjustment for inflation.

For example, suppose someone deposits $100 with a bank for one year, and they receive interest of $10 (before tax), so at the end of the year, their balance is $110 (before tax). In this case, regardless of the rate of inflation, the nominal interest rate is 10% per annum (before tax).

The real interest rate measures the growth in real value of the loan plus interest, taking inflation into account. The repayment of principal plus interest is measured in real terms compared against the buying power of the amount at the time it was borrowed, lent, deposited or invested.

If inflation is 10%, then the $110 in the account at the end of the year has the same purchasing power (that is, buys the same amount) as the $100 had a year ago. The real interest rate is zero in this case.

The real interest rate is given by the Fisher equation:

where p is the inflation rate. For low rates and short periods, the linear approximation applies:

The Fisher equation applies both ex ante and ex post. Ex ante, the rates are projected rates, whereas ex post, the rates are historical.

Market rates

There is a market for investments, including the money market, bond market, stock market, and currency market as well as retail banking.

Interest rates reflect:

- The risk-free cost of capital

- Expected inflation

- Risk premium

- Transaction costs

Inflationary expectations

According to the theory of rational expectations, borrowers and lenders form an expectation of inflation in the future. The acceptable nominal interest rate at which they are willing and able to borrow or lend includes the real interest rate they require to receive, or are willing and able to pay, plus the rate of inflation they expect.

Risk

The level of risk in investments is taken into consideration. Riskier investments such as shares and junk bonds are normally expected to deliver higher returns than safer ones like government bonds.

The additional return above the risk-free nominal interest rate which is expected from a risky investment is the risk premium. The risk premium an investor requires on an investment depends on the risk preferences of the investor. Evidence suggests that most lenders are risk-averse.[15]

A maturity risk premium applied to a longer-term investment reflects a higher perceived risk of default.

There are four kinds of risk:

- repricing risk

- basis risk

- yield curve risk

- optionality

Liquidity preference

Most investors prefer their money to be in cash rather than in less fungible investments. Cash is on hand to be spent immediately if the need arises, but some investments require time or effort to transfer into spendable form. The preference for cash is known as liquidity preference. A 1-year loan, for instance, is very liquid compared to a 10-year loan. A 10-year US Treasury bond, however, is still relatively liquid because it can easily be sold on the market.

A market model

A basic interest rate pricing model for an asset is

where

- in is the nominal interest rate on a given investment

- ir is the risk-free return to capital

- i*n is the nominal interest rate on a short-term risk-free liquid bond (such as U.S. Treasury bills).

- rp is a risk premium reflecting the length of the investment and the likelihood the borrower will default

- lp is a liquidity premium (reflecting the perceived difficulty of converting the asset into money and thus into goods).

- pe is the expected inflation rate.

Assuming perfect information, pe is the same for all participants in the market, and the interest rate model simplifies to

Spread

The spread of interest rates is the lending rate minus the deposit rate.[16] This spread covers operating costs for banks providing loans and deposits. A negative spread is where a deposit rate is higher than the lending rate.[17]

In macroeconomics

Output, unemployment and inflation

Interest rates affect economic activity broadly, which is the reason why they are normally the main instrument of the monetary policies conducted by central banks.[18] Changes in interest rates will affect firms' investment behaviour, either raising or lowering the opportunity cost of investing. Interest rate changes also affect asset prices like stock prices and house prices, which again influence households' consumption decisions through a wealth effect. Additionally, international interest rate differentials affect exchange rates and consequently exports and imports. These various channels are collectively known as the monetary transmission mechanism. Consumption, investment and net exports are all important components of aggregate demand. Consequently, by influencing the general interest rate level, monetary policy can affect overall demand for goods and services in the economy and hence output and employment.[19] Changes in employment will over time affect wage setting, which again affects pricing and consequently ultimately inflation. The relation between employment (or unemployment) and inflation is known as the Phillips curve.[18]

For economies maintaining a fixed exchange rate system, determining the interest rate is also an important instrument of monetary policy as international capital flows are in part determined by interest rate differentials between countries.[20]

Interest rate setting in the United States

The Federal Reserve (often referred to as 'the Fed') implements monetary policy largely by targeting the federal funds rate (FFR). This is the rate that banks charge each other for overnight loans of federal funds, which are the reserves held by banks at the Fed. Until the global financial crisis in 2008, the Fed relied on open market operations, i.e. selling and buying securities in the open market to adjust the supply of reserve balances so as to keep the FFR close to the Fed's target.[21] However, since 2008 the actual conduct of monetary policy implementation has changed considerably, the Fed using instead various administered interest rates (i.e., interest rates that are set directly by the Fed rather than being determined by the market forces of supply and demand) as the primary tools to steer short-term market interest rates towards the Fed's policy target.[22]

Impact on savings and pensions

Financial economists such as World Pensions Council (WPC) researchers have argued that durably low interest rates in most G20 countries will have an adverse impact on the funding positions of pension funds as "without returns that outstrip inflation, pension investors face the real value of their savings declining rather than ratcheting up over the next few years".[23] Current interest rates in savings accounts often fail to keep up with the pace of inflation.[24]

From 1982 until 2012, most Western economies experienced a period of low inflation combined with relatively high returns on investments across all asset classes including government bonds. This brought a certain sense of complacency[citation needed] amongst some pension actuarial consultants and regulators, making it seem reasonable to use optimistic economic assumptions to calculate the present value of future pension liabilities.

Mathematical note

Because interest and inflation are generally given as percentage increases, the formulae above are (linear) approximations.

For instance,

is only approximate. In reality, the relationship is

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk