A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

This article needs attention from an expert in linguistics. The specific problem is: There seems to be some confusion surrounding the chronology of Arabic's origination, including notably in the paragraph on Qaryat Al-Faw (also discussed on talk). There are major sourcing gaps from "Literary Arabic" onwards. (August 2022) |

Arabic (اَلْعَرَبِيَّةُ, al-ʿarabiyyah [al ʕaraˈbijːa] ⓘ or عَرَبِيّ, ʿarabīy [ˈʕarabiː] ⓘ or [ʕaraˈbij]) is a Central Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family spoken primarily in the Arab world.[14] The ISO assigns language codes to 32 varieties of Arabic, including its standard form of Literary Arabic, known as Modern Standard Arabic,[15] which is derived from Classical Arabic. This distinction exists primarily among Western linguists; Arabic speakers themselves generally do not distinguish between Modern Standard Arabic and Classical Arabic, but rather refer to both as al-ʿarabiyyatu l-fuṣḥā (اَلعَرَبِيَّةُ ٱلْفُصْحَىٰ[16] "the eloquent Arabic") or simply al-fuṣḥā (اَلْفُصْحَىٰ).

Arabic is the third most widespread official language after English and French,[17] one of six official languages of the United Nations,[18] and is the liturgical language of Islam.[19] Arabic is widely taught in schools and universities around the world and is used to varying degrees in workplaces, governments and the media.[20] During the Middle Ages, Arabic was a major vehicle of culture, especially in science, mathematics and philosophy. As a result, many European languages have also borrowed many words from it. Arabic influence, mainly in vocabulary, is seen in European languages—mainly Spanish and to a lesser extent Portuguese, Catalan, and Sicilian—owing to both the proximity of European and the long-lasting Arabic cultural and linguistic presence, mainly in Southern Iberia, during the Al-Andalus era. The Maltese language is a Semitic language developed from a dialect of Arabic and written in the Latin alphabet.[21] The Balkan languages, including Greek and Bulgarian, have acquired many words of Arabic origin, especially through direct contact with Ottoman Turkish.

Arabic has influenced many other languages around the globe throughout its history, especially languages of Muslim cultures and countries that were conquered by Muslims. Some of the most influenced languages are Persian, Turkish, Hindustani (Hindi and Urdu),[22] Kashmiri, Kurdish, Bosnian, Kazakh, Bengali, Malay (Indonesian and Malaysian), Maldivian, Pashto, Punjabi, Albanian, Armenian, Azerbaijani, Sicilian, Spanish, Greek, Bulgarian, Tagalog, Sindhi, Odia[23] Hebrew and Hausa and some languages in parts of Africa, such as Somali and Swahili. Conversely, Arabic has borrowed words from other languages, including Aramaic as well as Hebrew, Latin, Greek, Persian and to a lesser extent Turkish, English, French, and other Semitic languages.

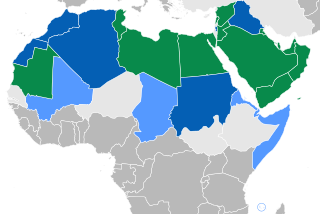

Arabic is spoken by as many as 380 million speakers, both native and non-native, in the Arab world,[1] making it the fifth most spoken language in the world,[24] and the fourth most used language on the internet in terms of users.[25][26] It also serves as the liturgical language of more than 1.9 billion Muslims.[27] In 2011, Bloomberg Businessweek ranked Arabic the fourth most useful language for business, after English, Standard Mandarin Chinese, and French.[28] Arabic is written with the Arabic alphabet, which is an abjad script and is written from right to left, although the spoken varieties are sometimes written in ASCII Latin from left to right with no standardized orthography.

Classification

Arabic is usually classified as a Central Semitic language. Linguists still differ as to the best classification of Semitic language sub-groups.[29] The Semitic languages changed between Proto-Semitic and the emergence of Central Semitic languages, particularly in grammar. Innovations of the Central Semitic languages—all maintained in Arabic—include:

- The conversion of the suffix-conjugated stative formation (jalas-) into a past tense.

- The conversion of the prefix-conjugated preterite-tense formation (yajlis-) into a present tense.

- The elimination of other prefix-conjugated mood/aspect forms (e.g., a present tense formed by doubling the middle root, a perfect formed by infixing a /t/ after the first root consonant, probably a jussive formed by a stress shift) in favor of new moods formed by endings attached to the prefix-conjugation forms (e.g., -u for indicative, -a for subjunctive, no ending for jussive, -an or -anna for energetic).

- The development of an internal passive.

There are several features which Classical Arabic, the modern Arabic varieties, as well as the Safaitic and Hismaic inscriptions share which are unattested in any other Central Semitic language variety, including the Dadanitic and Taymanitic languages of the northern Hejaz. These features are evidence of common descent from a hypothetical ancestor, Proto-Arabic.[30][31] The following features of Proto-Arabic can be reconstructed with confidence:[32]

- negative particles m * /mā/; lʾn */lā-ʾan/ to Classical Arabic lan

- mafʿūl G-passive participle

- prepositions and adverbs f, ʿn, ʿnd, ḥt, ʿkdy

- a subjunctive in -a

- t-demonstratives

- leveling of the -at allomorph of the feminine ending

- ʾn complementizer and subordinator

- the use of f- to introduce modal clauses

- independent object pronoun in (ʾ)y

- vestiges of nunation

On the other hand, several Arabic varieties are closer to other Semitic languages and maintain features not found in Classical Arabic, indicating that these varieties cannot have developed from Classical Arabic.[33][34] Thus, Arabic vernaculars do not descend from Classical Arabic:[35] Classical Arabic is a sister language rather than their direct ancestor.[30]

History

Old Arabic

Arabia had a wide variety of Semitic languages in antiquity. The term "Arab" was initially used to describe those living in the Arabian Peninsula, as perceived by geographers from ancient Greece.[36][37] In the southwest, various Central Semitic languages both belonging to and outside the Ancient South Arabian family (e.g. Southern Thamudic) were spoken. It is believed that the ancestors of the Modern South Arabian languages (non-Central Semitic languages) were spoken in southern Arabia at this time. To the north, in the oases of northern Hejaz, Dadanitic and Taymanitic held some prestige as inscriptional languages. In Najd and parts of western Arabia, a language known to scholars as Thamudic C is attested.[38]

In eastern Arabia, inscriptions in a script derived from ASA attest to a language known as Hasaitic. On the northwestern frontier of Arabia, various languages known to scholars as Thamudic B, Thamudic D, Safaitic, and Hismaic are attested. The last two share important isoglosses with later forms of Arabic, leading scholars to theorize that Safaitic and Hismaic are early forms of Arabic and that they should be considered Old Arabic.[38]

Linguists generally believe that "Old Arabic", a collection of related dialects that constitute the precursor of Arabic, first emerged during the Iron Age.[29] Previously, the earliest attestation of Old Arabic was thought to be a single 1st century CE inscription in Sabaic script at Qaryat al-Faw, in southern present-day Saudi Arabia. However, this inscription does not participate in several of the key innovations of the Arabic language group, such as the conversion of Semitic mimation to nunation in the singular. It is best reassessed as a separate language on the Central Semitic dialect continuum.[39]

It was also thought that Old Arabic coexisted alongside—and then gradually displaced—epigraphic Ancient North Arabian (ANA), which was theorized to have been the regional tongue for many centuries. ANA, despite its name, was considered a very distinct language, and mutually unintelligible, from "Arabic". Scholars named its variant dialects after the towns where the inscriptions were discovered (Dadanitic, Taymanitic, Hismaic, Safaitic).[29] However, most arguments for a single ANA language or language family were based on the shape of the definite article, a prefixed h-. It has been argued that the h- is an archaism and not a shared innovation, and thus unsuitable for language classification, rendering the hypothesis of an ANA language family untenable.[40] Safaitic and Hismaic, previously considered ANA, should be considered Old Arabic due to the fact that they participate in the innovations common to all forms of Arabic.[38]

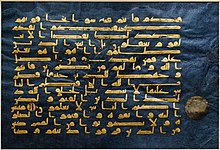

The earliest attestation of continuous Arabic text in an ancestor of the modern Arabic script are three lines of poetry by a man named Garm(')allāhe found in En Avdat, Israel, and dated to around 125 CE.[41] This is followed by the Namara inscription, an epitaph of the Lakhmid king Imru' al-Qays bar 'Amro, dating to 328 CE, found at Namaraa, Syria. From the 4th to the 6th centuries, the Nabataean script evolved into the Arabic script recognizable from the early Islamic era.[42] There are inscriptions in an undotted, 17-letter Arabic script dating to the 6th century CE, found at four locations in Syria (Zabad, Jebel Usays, Harran, Umm el-Jimal). The oldest surviving papyrus in Arabic dates to 643 CE, and it uses dots to produce the modern 28-letter Arabic alphabet. The language of that papyrus and of the Qur'an is referred to by linguists as "Quranic Arabic", as distinct from its codification soon thereafter into "Classical Arabic".[29]

Classical Arabic

In late pre-Islamic times, a transdialectal and transcommunal variety of Arabic emerged in the Hejaz, which continued living its parallel life after literary Arabic had been institutionally standardized in the 2nd and 3rd century of the Hijra, most strongly in Judeo-Christian texts, keeping alive ancient features eliminated from the "learned" tradition (Classical Arabic).[43] This variety and both its classicizing and "lay" iterations have been termed Middle Arabic in the past, but they are thought to continue an Old Higazi register. It is clear that the orthography of the Quran was not developed for the standardized form of Classical Arabic; rather, it shows the attempt on the part of writers to record an archaic form of Old Higazi.[citation needed]

In the late 6th century AD, a relatively uniform intertribal "poetic koine" distinct from the spoken vernaculars developed based on the Bedouin dialects of Najd, probably in connection with the court of al-Ḥīra. During the first Islamic century, the majority of Arabic poets and Arabic-writing persons spoke Arabic as their mother tongue. Their texts, although mainly preserved in far later manuscripts, contain traces of non-standardized Classical Arabic elements in morphology and syntax.[citation needed]

Standardization

Abu al-Aswad al-Du'ali (c. 603–689) is credited with standardizing Arabic grammar, or an-naḥw (النَّحو "the way"[44]), and pioneering a system of diacritics to differentiate consonants (نقط الإعجام nuqaṭu‿l-i‘jām "pointing for non-Arabs") and indicate vocalization (التشكيل at-tashkīl).[45] Al-Khalil ibn Ahmad al-Farahidi (718–786) compiled the first Arabic dictionary, Kitāb al-'Ayn (كتاب العين "The Book of the Letter ع"), and is credited with establishing the rules of Arabic prosody.[46] Al-Jahiz (776–868) proposed to Al-Akhfash al-Akbar an overhaul of the grammar of Arabic, but it would not come to pass for two centuries.[47] The standardization of Arabic reached completion around the end of the 8th century. The first comprehensive description of the ʿarabiyya "Arabic", Sībawayhi's al-Kitāb, is based first of all upon a corpus of poetic texts, in addition to Qur'an usage and Bedouin informants whom he considered to be reliable speakers of the ʿarabiyya.[48]

Spread

Arabic spread with the spread of Islam. Following the early Muslim conquests, Arabic gained vocabulary from Middle Persian and Turkish.[49] In the early Abbasid period, many Classical Greek terms entered Arabic through translations carried out at Baghdad's House of Wisdom.[49]

By the 8th century, knowledge of Classical Arabic had become an essential prerequisite for rising into the higher classes throughout the Islamic world, both for Muslims and non-Muslims. For example, Maimonides, the Andalusi Jewish philosopher, authored works in Judeo-Arabic—Arabic written in Hebrew script.[50]

Development

Ibn Jinni of Mosul, a pioneer in phonology, wrote prolifically in the 10th century on Arabic morphology and phonology in works such as Kitāb Al-Munṣif, Kitāb Al-Muḥtasab, and Kitāb Al-Khaṣāʾiṣ .[51]

Ibn Mada' of Cordoba (1116–1196) realized the overhaul of Arabic grammar first proposed by Al-Jahiz 200 years prior.[47]

The Maghrebi lexicographer Ibn Manzur compiled Lisān al-ʿArab (لسان العرب, "Tongue of Arabs"), a major reference dictionary of Arabic, in 1290.[52]

Neo-Arabic

Charles Ferguson's koine theory claims that the modern Arabic dialects collectively descend from a single military koine that sprang up during the Islamic conquests; this view has been challenged in recent times. Ahmad al-Jallad proposes that there were at least two considerably distinct types of Arabic on the eve of the conquests: Northern and Central (Al-Jallad 2009). The modern dialects emerged from a new contact situation produced following the conquests. Instead of the emergence of a single or multiple koines, the dialects contain several sedimentary layers of borrowed and areal features, which they absorbed at different points in their linguistic histories.[48] According to Veersteegh and Bickerton, colloquial Arabic dialects arose from pidginized Arabic formed from contact between Arabs and conquered peoples. Pidginization and subsequent creolization among Arabs and arabized peoples could explain relative morphological and phonological simplicity of vernacular Arabic compared to Classical and MSA.[53][54]

In around the 11th and 12th centuries in al-Andalus, the zajal and muwashah poetry forms developed in the dialectical Arabic of Cordoba and the Maghreb.[55]

Nahda

The Nahda was a cultural and especially literary renaissance of the 19th century in which writers sought "to fuse Arabic and European forms of expression."[56] According to James L. Gelvin, "Nahda writers attempted to simplify the Arabic language and script so that it might be accessible to a wider audience."[56]

In the wake of the industrial revolution and European hegemony and colonialism, pioneering Arabic presses, such as the Amiri Press established by Muhammad Ali (1819), dramatically changed the diffusion and consumption of Arabic literature and publications.[57] Rifa'a al-Tahtawi proposed the establishment of Madrasat al-Alsun in 1836 and led a translation campaign that highlighted the need for a lexical injection in Arabic, to suit concepts of the industrial and post-industrial age (such as sayyārah سَيَّارَة 'automobile' or bākhirah باخِرة 'steamship').[58][59]

In response, a number of Arabic academies modeled after the Académie française were established with the aim of developing standardized additions to the Arabic lexicon to suit these transformations,[60] first in Damascus (1919), then in Cairo (1932), Baghdad (1948), Rabat (1960), Amman (1977), Khartum (1993), and Tunis (1993).[61] They review language development, monitor new words and approve the inclusion of new words into their published standard dictionaries. They also publish old and historical Arabic manuscripts.[citation needed]

In 1997, a bureau of Arabization standardization was added to the Educational, Cultural, and Scientific Organization of the Arab League.[61] These academies and organizations have worked toward the Arabization of the sciences, creating terms in Arabic to describe new concepts, toward the standardization of these new terms throughout the Arabic-speaking world, and toward the development of Arabic as a world language.[61] This gave rise to what Western scholars call Modern Standard Arabic. From the 1950s, Arabization became a postcolonial nationalist policy in countries such as Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco,[62] and Sudan.[63]

Classical, Modern Standard and spoken Arabic

Arabic usually refers to Standard Arabic, which Western linguists divide into Classical Arabic and Modern Standard Arabic.[64] It could also refer to any of a variety of regional vernacular Arabic dialects, which are not necessarily mutually intelligible.

Classical Arabic is the language found in the Quran, used from the period of Pre-Islamic Arabia to that of the Abbasid Caliphate. Classical Arabic is prescriptive, according to the syntactic and grammatical norms laid down by classical grammarians (such as Sibawayh) and the vocabulary defined in classical dictionaries (such as the Lisān al-ʻArab).[citation needed]

Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) largely follows the grammatical standards of Classical Arabic and uses much of the same vocabulary. However, it has discarded some grammatical constructions and vocabulary that no longer have any counterpart in the spoken varieties and has adopted certain new constructions and vocabulary from the spoken varieties. Much of the new vocabulary is used to denote concepts that have arisen in the industrial and post-industrial era, especially in modern times.[65]

Due to its grounding in Classical Arabic, Modern Standard Arabic is removed over a millennium from everyday speech, which is construed as a multitude of dialects of this language. These dialects and Modern Standard Arabic are described by some scholars as not mutually comprehensible. The former are usually acquired in families, while the latter is taught in formal education settings. However, there have been studies reporting some degree of comprehension of stories told in the standard variety among preschool-aged children.[66]

The relation between Modern Standard Arabic and these dialects is sometimes compared to that of Classical Latin and Vulgar Latin vernaculars (which became Romance languages) in medieval and early modern Europe.[64]

MSA is the variety used in most current, printed Arabic publications, spoken by some of the Arabic media across North Africa and the Middle East, and understood by most educated Arabic speakers. "Literary Arabic" and "Standard Arabic" (فُصْحَى fuṣḥá) are less strictly defined terms that may refer to Modern Standard Arabic or Classical Arabic.[citation needed]

Some of the differences between Classical Arabic (CA) and Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) are as follows:[citation needed]

- Certain grammatical constructions of CA that have no counterpart in any modern vernacular dialect (e.g., the energetic mood) are almost never used in Modern Standard Arabic.[citation needed]

- Case distinctions are very rare in Arabic vernaculars. As a result, MSA is generally composed without case distinctions in mind, and the proper cases are added after the fact, when necessary. Because most case endings are noted using final short vowels, which are normally left unwritten in the Arabic script, it is unnecessary to determine the proper case of most words. The practical result of this is that MSA, like English and Standard Chinese, is written in a strongly determined word order and alternative orders that were used in CA for emphasis are rare. In addition, because of the lack of case marking in the spoken varieties, most speakers cannot consistently use the correct endings in extemporaneous speech. As a result, spoken MSA tends to drop or regularize the endings except when reading from a prepared text.[citation needed]

- The numeral system in CA is complex and heavily tied in with the case system. This system is never used in MSA, even in the most formal of circumstances; instead, a greatly simplified system is used, approximating the system of the conservative spoken varieties.[citation needed]

MSA uses much Classical vocabulary (e.g., dhahaba 'to go') that is not present in the spoken varieties, but deletes Classical words that sound obsolete in MSA. In addition, MSA has borrowed or coined many terms for concepts that did not exist in Quranic times, and MSA continues to evolve.[67] Some words have been borrowed from other languages—notice that transliteration mainly indicates spelling and not real pronunciation (e.g., فِلْم film 'film' or ديمقراطية dīmuqrāṭiyyah 'democracy').[citation needed]

The current preference is to avoid direct borrowings, preferring to either use loan translations (e.g., فرع farʻ 'branch', also used for the branch of a company or organization; جناح janāḥ 'wing', is also used for the wing of an airplane, building, air force, etc.), or to coin new words using forms within existing roots (استماتة istimātah 'apoptosis', using the root موت m?pojem=t 'death' put into the Xth form, or جامعة jāmiʻah 'university', based on جمع jamaʻa 'to gather, unite'; جمهورية jumhūriyyah 'republic', based on جمهور jumhūr 'multitude'). An earlier tendency was to redefine an older word although this has fallen into disuse (e.g., هاتف hātif 'telephone' < 'invisible caller (in Sufism)'; جريدة jarīdah 'newspaper' < 'palm-leaf stalk').[citation needed]

Colloquial or dialectal Arabic refers to the many national or regional varieties which constitute the everyday spoken language. Colloquial Arabic has many regional variants; geographically distant varieties usually differ enough to be mutually unintelligible, and some linguists consider them distinct languages.[68] However, research indicates a high degree of mutual intelligibility between closely related Arabic variants for native speakers listening to words, sentences, and texts; and between more distantly related dialects in interactional situations.[69]

The varieties are typically unwritten. They are often used in informal spoken media, such as soap operas and talk shows,[71] as well as occasionally in certain forms of written media such as poetry and printed advertising.

Hassaniya Arabic, Maltese, and Cypriot Arabic are only varieties of modern Arabic to have acquired official recognition.[72] Hassaniya is official in Mali[73] and recognized as a minority language in Morocco,[74] while the Senegalese government adopted the Latin script to write it.[12] Maltese is official in (predominantly Catholic) Malta and written with the Latin script. Linguists agree that it is a variety of spoken Arabic, descended from Siculo-Arabic, though it has experienced extensive changes as a result of sustained and intensive contact with Italo-Romance varieties, and more recently also with English. Due to "a mix of social, cultural, historical, political, and indeed linguistic factors", many Maltese people today consider their language Semitic but not a type of Arabic.[75] Cypriot Arabic is recognized as a minority language in Cyprus.[76]

Status and usage

Diglossia

The sociolinguistic situation of Arabic in modern times provides a prime example of the linguistic phenomenon of diglossia, which is the normal use of two separate varieties of the same language, usually in different social situations. Tawleed is the process of giving a new shade of meaning to an old classical word. For example, al-hatif lexicographically means the one whose sound is heard but whose person remains unseen. Now the term al-hatif is used for a telephone. Therefore, the process of tawleed can express the needs of modern civilization in a manner that would appear to be originally Arabic.[77]

In the case of Arabic, educated Arabs of any nationality can be assumed to speak both their school-taught Standard Arabic as well as their native dialects, which depending on the region may be mutually unintelligible.[78][79][80][81][82] Some of these dialects can be considered to constitute separate languages which may have "sub-dialects" of their own.[83] When educated Arabs of different dialects engage in conversation (for example, a Moroccan speaking with a Lebanese), many speakers code-switch back and forth between the dialectal and standard varieties of the language, sometimes even within the same sentence.

The issue of whether Arabic is one language or many languages is politically charged, in the same way it is for the varieties of Chinese, Hindi and Urdu, Serbian and Croatian, Scots and English, etc. In contrast to speakers of Hindi and Urdu who claim they cannot understand each other even when they can, speakers of the varieties of Arabic will claim they can all understand each other even when they cannot.[84]

While there is a minimum level of comprehension between all Arabic dialects, this level can increase or decrease based on geographic proximity: for example, Levantine and Gulf speakers understand each other much better than they do speakers from the Maghreb. The issue of diglossia between spoken and written language is a complicating factor: A single written form, differing sharply from any of the spoken varieties learned natively, unites several sometimes divergent spoken forms. For political reasons, Arabs mostly assert that they all speak a single language, despite mutual incomprehensibility among differing spoken versions.[85]

From a linguistic standpoint, it is often said that the various spoken varieties of Arabic differ among each other collectively about as much as the Romance languages.[86] This is an apt comparison in a number of ways. The period of divergence from a single spoken form is similar—perhaps 1500 years for Arabic, 2000 years for the Romance languages. Also, while it is comprehensible to people from the Maghreb, a linguistically innovative variety such as Moroccan Arabic is essentially incomprehensible to Arabs from the Mashriq, much as French is incomprehensible to Spanish or Italian speakers but relatively easily learned by them. This suggests that the spoken varieties may linguistically be considered separate languages.[citation needed]

Status in the Arab world vis-à-vis other languages

With the sole example of Medieval linguist Abu Hayyan al-Gharnati – who, while a scholar of the Arabic language, was not ethnically Arab – Medieval scholars of the Arabic language made no efforts at studying comparative linguistics, considering all other languages inferior.[87]

In modern times, the educated upper classes in the Arab world have taken a nearly opposite view. Yasir Suleiman wrote in 2011 that "studying and knowing English or French in most of the Middle East and North Africa have become a badge of sophistication and modernity and ... feigning, or asserting, weakness or lack of facility in Arabic is sometimes paraded as a sign of status, class, and perversely, even education through a mélange of code-switching practises."[88]

As a foreign language

Arabic has been taught worldwide in many elementary and secondary schools, especially Muslim schools. Universities around the world have classes that teach Arabic as part of their foreign languages, Middle Eastern studies, and religious studies courses. Arabic language schools exist to assist students to learn Arabic outside the academic world. There are many Arabic language schools in the Arab world and other Muslim countries. Because the Quran is written in Arabic and all Islamic terms are in Arabic, millions[89] of Muslims (both Arab and non-Arab) study the language.

Software and books with tapes are an important part of Arabic learning, as many of Arabic learners may live in places where there are no academic or Arabic language school classes available. Radio series of Arabic language classes are also provided from some radio stations.[90] A number of websites on the Internet provide online classes for all levels as a means of distance education; most teach Modern Standard Arabic, but some teach regional varieties from numerous countries.[91]

Vocabulary

Lexicography

Pre-modern Arabic lexicography

The tradition of Arabic lexicography extended for about a millennium before the modern period.[92] Early lexicographers (لُغَوِيُّون lughawiyyūn) sought to explain words in the Quran that were unfamiliar or had a particular contextual meaning, and to identify words of non-Arabic origin that appear in the Quran.[92] They gathered shawāhid (شَوَاهِد 'instances of attested usage') from poetry and the speech of the Arabs—particularly the Bedouin ʾaʿrāb (أَعْراب) who were perceived to speak the “purest,” most eloquent form of Arabic—initiating a process of jamʿu‿l-luɣah (جمع اللغة 'compiling the language') which took place over the 8th and early 9th centuries.[92]

Kitāb al-'Ayn (c. 8th century), attributed to Al-Khalil ibn Ahmad al-Farahidi, is considered the first lexicon to include all Arabic roots; it sought to exhaust all possible root permutations—later called taqālīb (تقاليب)—calling those that are actually used mustaʿmal (مستعمَل) and those that are not used muhmal (مُهمَل).[92] Lisān al-ʿArab (1290) by Ibn Manzur gives 9,273 roots, while Tāj al-ʿArūs (1774) by Murtada az-Zabidi gives 11,978 roots.[92]

This lexicographic tradition was traditionalist and corrective in nature—holding that linguistic correctness and eloquence derive from Qurʾānic usage, pre-Islamic poetry, and Bedouin speech—positioning itself against laḥnu‿l-ʿāmmah (لَحْن العامة), the solecism it viewed as defective.[92]

Western lexicography of Arabic

In the second half of the 19th century, the British Arabist Edward William Lane, working with the Egyptian scholar Ibrāhīm Abd al-Ghaffār ad-Dasūqī,[93] compiled the Arabic–English Lexicon by translating material from earlier Arabic lexica into English.[94] The German Arabist Hans Wehr, with contributions from Hedwig Klein,[95] compiled the Arabisches Wörterbuch für die Schriftsprache der Gegenwart (1952), later translated into English as A Dictionary of Modern Written Arabic (1961), based on established usage, especially in literature.[96]

Modern Arabic lexicography

The Academy of the Arabic Language in Cairo sought to publish a historical dictionary of Arabic in the vein of the Oxford English Dictionary, tracing the changes of meanings and uses of Arabic words over time.[97] A first volume of Al-Muʿjam al-Kabīr was published in 1956 under the leadership of Taha Hussein.[98] The project is not yet complete; its 15th volume, covering the letter ṣād, was published in 2022.[99]

Loanwords

The most important sources of borrowings into (pre-Islamic) Arabic are from the related (Semitic) languages Aramaic,[100] which used to be the principal, international language of communication throughout the ancient Near and Middle East, and Ethiopic. Many cultural, religious and political terms have entered Arabic from Iranian languages, notably Middle Persian, Parthian, and (Classical) Persian,[101] and Hellenistic Greek (kīmiyāʼ has as origin the Greek khymia, meaning in that language the melting of metals; see Roger Dachez, Histoire de la Médecine de l'Antiquité au XXe siècle, Tallandier, 2008, p. 251), alembic (distiller) from ambix (cup), almanac (climate) from almenichiakon (calendar).

For the origin of the last three borrowed words, see Alfred-Louis de Prémare, Foundations of Islam, Seuil, L'Univers Historique, 2002. Some Arabic borrowings from Semitic or Persian languages are, as presented in De Prémare's above-cited book: [citation needed]

- madīnah/medina (مدينة, city or city square), a word of Aramaic origin ܡܕ݂ܝܼܢ݇ܬܵܐ məḏī(n)ttā (in which it means "state/city").[citation needed]

- jazīrah (جزيرة), as in the well-known form الجزيرة "Al-Jazeera", means "island" and has its origin in the Syriac ܓܵܙܲܪܬܵܐ gāzartā.[citation needed]

- lāzaward (لازورد) is taken from Persian لاژورد lājvard, the name of a blue stone, lapis lazuli. This word was borrowed in several European languages to mean (light) blue – azure in English, azur in French and azul in Portuguese and Spanish.[citation needed]

A comprehensive overview of the influence of other languages on Arabic is found in Lucas & Manfredi (2020).[102]

Influence of Arabic on other languages

The influence of Arabic has been most important in Islamic countries, because it is the language of the Islamic sacred book, the Quran. Arabic is also an important source of vocabulary for languages such as Amharic, Azerbaijani, Baluchi, Bengali, Berber, Bosnian, Chaldean, Chechen, Chittagonian, Croatian, Dagestani, Dhivehi, English, German, Gujarati, Hausa, Hindi, Kazakh, Kurdish, Kutchi, Kyrgyz, Malay (Malaysian and Indonesian), Pashto, Persian, Punjabi, Rohingya, Romance languages (French, Catalan, Italian, Portuguese, Sicilian, Spanish, etc.) Saraiki, Sindhi, Somali, Sylheti, Swahili, Tagalog, Tigrinya, Turkish, Turkmen, Urdu, Uyghur, Uzbek, Visayan and Wolof, as well as other languages in countries where these languages are spoken.[102] Modern Hebrew has been also influenced by Arabic especially during the process of revival, as MSA was used as a source for modern Hebrew vocabulary and roots.[103]

English has many Arabic loanwords, some directly, but most via other Mediterranean languages. Examples of such words include admiral, adobe, alchemy, alcohol, algebra, algorithm, alkaline, almanac, amber, arsenal, assassin, candy, carat, cipher, coffee, cotton, ghoul, hazard, jar, kismet, lemon, loofah, magazine, mattress, sherbet, sofa, sumac, tariff, and zenith.[104] Other languages such as Maltese[105] and Kinubi derive ultimately from Arabic, rather than merely borrowing vocabulary or grammatical rules.

Terms borrowed range from religious terminology (like Berber taẓallit, "prayer", from salat (صلاة ṣalāh)), academic terms (like Uyghur mentiq, "logic"), and economic items (like English coffee) to placeholders (like Spanish fulano, "so-and-so"), everyday terms (like Hindustani lekin, "but", or Spanish taza and French tasse, meaning "cup"), and expressions (like Catalan a betzef, "galore, in quantity"). Most Berber varieties (such as Kabyle), along with Swahili, borrow some numbers from Arabic. Most Islamic religious terms are direct borrowings from Arabic, such as صلاة (ṣalāh), "prayer", and إمام (imām), "prayer leader".[citation needed]

In languages not directly in contact with the Arab world, Arabic loanwords are often transferred indirectly via other languages rather than being transferred directly from Arabic. For example, most Arabic loanwords in Hindustani and Turkish entered through Persian. Older Arabic loanwords in Hausa were borrowed from Kanuri. Most Arabic loanwords in Yoruba entered through Hausa.[citation needed]

Arabic words made their way into several West African languages as Islam spread across the Sahara. Variants of Arabic words such as كتاب kitāb ("book") have spread to the languages of African groups who had no direct contact with Arab traders.[106]

Since, throughout the Islamic world, Arabic occupied a position similar to that of Latin in Europe, many of the Arabic concepts in the fields of science, philosophy, commerce, etc. were coined from Arabic roots by non-native Arabic speakers, notably by Aramaic and Persian translators, and then found their way into other languages. This process of using Arabic roots, especially in Kurdish and Persian, to translate foreign concepts continued through to the 18th and 19th centuries, when swaths of Arab-inhabited lands were under Ottoman rule.[citation needed]

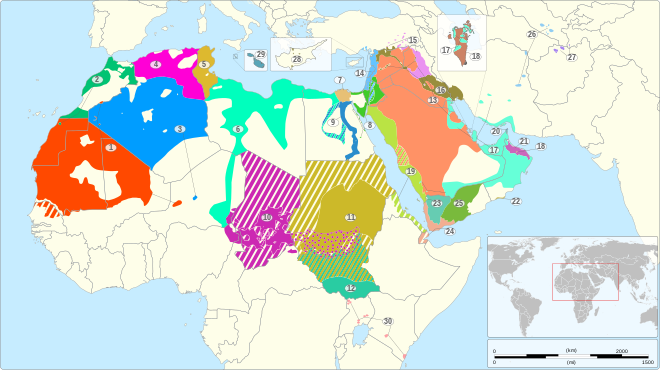

Spoken varieties

- 1: Hassaniyya

- 9: Saidi Arabic

- 10: Chadian Arabic

- 11: Sudanese Arabic

- 13: Najdi Arabic

- 14: Levantine Arabic

- 17: Gulf Arabic

- 18: Baharna Arabic

- 19: Hijazi Arabic

- 20: Shihhi Arabic

- 21: Omani Arabic

- 22: Dhofari Arabic

- 23: Sanaani Arabic

- 25: Hadrami Arabic

- 26: Uzbeki Arabic

- 27: Tajiki Arabic

- 28: Cypriot Arabic

- 29: Maltese

- 30: Nubi

- Sparsely populated area or no indigenous Arabic speakers

- Solid area fill: variety natively spoken by at least 25% of the population of that area or variety indigenous to that area only

- Hatched area fill: minority scattered over the area

- Dotted area fill: speakers of this variety are mixed with speakers of other Arabic varieties in the area

Colloquial Arabic is a collective term for the spoken dialects of Arabic used throughout the Arab world, which differ radically from the literary language. The main dialectal division is between the varieties within and outside of the Arabian peninsula, followed by that between sedentary varieties and the much more conservative Bedouin varieties. All the varieties outside of the Arabian peninsula, which include the large majority of speakers, have many features in common with each other that are not found in Classical Arabic. This has led researchers to postulate the existence of a prestige koine dialect in the one or two centuries immediately following the Arab conquest, whose features eventually spread to all newly conquered areas. These features are present to varying degrees inside the Arabian peninsula. Generally, the Arabian peninsula varieties have much more diversity than the non-peninsula varieties, but these have been understudied.[citation needed]

Within the non-peninsula varieties, the largest difference is between the non-Egyptian North African dialects, especially Moroccan Arabic, and the others. Moroccan Arabic in particular is hardly comprehensible to Arabic speakers east of Libya (although the converse is not true, in part due to the popularity of Egyptian films and other media).[citation needed]

One factor in the differentiation of the dialects is influence from the languages previously spoken in the areas, which have typically provided many new words and have sometimes also influenced pronunciation or word order. However, a more weighty factor for most dialects is, as among Romance languages, retention (or change of meaning) of different classical forms. Thus Iraqi aku, Levantine fīh and North African kayən all mean 'there is', and all come from Classical Arabic forms (yakūn, fīhi, kā'in respectively), but now sound very different.[citation needed]

Koiné

According to Charles A. Ferguson,[108] the following are some of the characteristic features of the koiné that underlies all the modern dialects outside the Arabian peninsula. Although many other features are common to most or all of these varieties, Ferguson believes that these features in particular are unlikely to have evolved independently more than once or twice and together suggest the existence of the koine:

- Loss of the dual number except on nouns, with consistent plural agreement (cf. feminine singular agreement in plural inanimates).

- Change of a to i in many affixes (e.g., non-past-tense prefixes ti- yi- ni-; wi- 'and'; il- 'the'; feminine -it in the construct state).

- Loss of third-weak verbs ending in w (which merge with verbs ending in y).

- Reformation of geminate verbs, e.g., ḥalaltu 'I untied' → ḥalēt(u).

- Conversion of separate words lī 'to me', laka 'to you', etc. into indirect-object clitic suffixes.

- Certain changes in the cardinal number system, e.g., khamsat ayyām 'five days' → kham(a)s tiyyām, where certain words have a special plural with prefixed t.

- Loss of the feminine elative (comparative).

- Adjective plurals of the form kibār 'big' → kubār.

- Change of nisba suffix -iyy > i.

- Certain lexical items, e.g., jāb 'bring' < jāʼa bi- 'come with'; shāf 'see'; ēsh 'what' (or similar) < ayyu shayʼ 'which thing'; illi (relative pronoun).

- Merger of /ɮˤ/ and /ðˤ/.

Dialect groups

- Egyptian Arabic is spoken by 67 million people in Egypt.[109] It is one of the most understood varieties of Arabic, due in large part to the widespread distribution of Egyptian films and television shows throughout the Arabic-speaking world

- Levantine Arabic is spoken by about 44 million people in Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, Palestine, Israel, and Turkey.[110]

- Lebanese Arabic is a variety of Levantine Arabic spoken primarily in Lebanon.

- Jordanian Arabic is a continuum of mutually intelligible varieties of Levantine Arabic spoken by the population of the Kingdom of Jordan.

- Palestinian Arabic is a name of several dialects of the subgroup of Levantine Arabic spoken by the Palestinians in Palestine, by Arab citizens of Israel and in most Palestinian populations around the world.

- Samaritan Arabic, spoken by only several hundred in the Nablus region

- Cypriot Maronite Arabic, spoken in Cyprus by around 9,800 people (2013 UNSD)[111]

- Maghrebi Arabic, also called "Darija" spoken by about 70 million people in Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia and Libya. It also forms the basis of Maltese via the extinct Sicilian Arabic dialect.[112] Maghrebi Arabic is very hard to understand for Arabic speakers from the Mashriq or Mesopotamia, the most comprehensible being Libyan Arabic and the most difficult Moroccan Arabic. The others such as Algerian Arabic can be considered in between the two in terms of difficulty.

- Libyan Arabic spoken in Libya and neighboring countries.

- Tunisian Arabic spoken in Tunisia and North-eastern Algeria

- Algerian Arabic spoken in Algeria

- Judeo-Algerian Arabic was spoken by Jews in Algeria until 1962

- Moroccan Arabic spoken in Morocco

- Hassaniya Arabic (3 million speakers), spoken in Mauritania, Western Sahara, some parts of the Azawad in northern Mali, southern Morocco and south-western Algeria.

- Andalusian Arabic, spoken in Spain until the 16th century.

- Siculo-Arabic (Sicilian Arabic), was spoken in Sicily and Malta between the end of the 9th century and the end of the 12th century and eventually evolved into the Maltese language.

- Maltese, spoken on the island of Malta, is the only fully separate standardized language to have originated from an Arabic dialect, the extinct Siculo-Arabic dialect, with independent literary norms. Maltese has evolved independently of Modern Standard Arabic and its varieties into a standardized language over the past 800 years in a gradual process of Latinisation.[113][114] Maltese is therefore considered an exceptional descendant of Arabic that has no diglossic relationship with Standard Arabic or Classical Arabic.[115] Maltese is different from Arabic and other Semitic languages since its morphology has been deeply influenced by Romance languages, Italian and Sicilian.[116] It is the only Semitic language written in the Latin script. In terms of basic everyday language, speakers of Maltese are reported to be able to understand less than a third of what is said to them in Tunisian Arabic,[117] which is related to Siculo-Arabic,[112] whereas speakers of Tunisian are able to understand about 40% of what is said to them in Maltese.[118] This asymmetric intelligibility is considerably lower than the mutual intelligibility found between Maghrebi Arabic dialects.[119] Maltese has its own dialects, with urban varieties of Maltese being closer to Standard Maltese than rural varieties.[120]

- Mesopotamian Arabic, spoken by about 41.2 million people in Iraq (where it is called "Aamiyah"), eastern Syria and southwestern Iran (Khuzestan) and in the southeastern of Turkey (in the eastern Mediterranean, Southeastern Anatolia Region)

- North Mesopotamian Arabic is a spoken north of the Hamrin Mountains in Iraq, in western Iran, northern Syria, and in southeastern Turkey (in the eastern Mediterranean Region, Southeastern Anatolia Region, and southern Eastern Anatolia Region).[121]

- Judeo-Mesopotamian Arabic, also known as Iraqi Judeo Arabic and Yahudic, is a variety of Arabic spoken by Iraqi Jews of Mosul.

- Baghdad Arabic is the Arabic dialect spoken in Baghdad, and the surrounding cities and it is a subvariety of Mesopotamian Arabic.

- Baghdad Jewish Arabic is the dialect spoken by the Iraqi Jews of Baghdad. Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Arabic_language

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk