A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

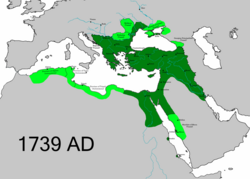

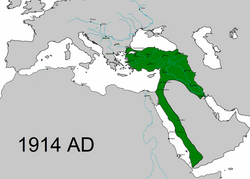

The Ottoman Empire,[j] historically and colloquially known as the Turkish Empire,[22][23] was an imperial realm[k] that spanned much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Central Europe between the early 16th and early 18th centuries.[24][25][26]

The empire emerged from a beylik, or principality, founded in northwestern Anatolia in 1299 by the Turkoman tribal leader Osman I. His successors conquered much of Anatolia and expanded into the Balkans by the mid 14th century, transforming their petty kingdom into a transcontinental empire. The Ottomans ended the Byzantine Empire with the conquest of Constantinople in 1453 by Mehmed II, which marked the Ottomans' emergence as a major regional power. Under Suleiman the Magnificent (1520–1566), the empire reached the peak of its power, prosperity, and political development. By the start of the 17th century, the Ottomans presided over 32 provinces and numerous vassal states, which over time were either absorbed into the Empire or granted various degrees of autonomy.[l] With its capital at Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul) and control over a significant portion of the Mediterranean Basin, the Ottoman Empire was at the centre of interactions between the Middle East and Europe for six centuries.

While the Ottoman Empire was once thought to have entered a period of decline after the death of Suleiman the Magnificent, modern academic consensus posits that the empire continued to maintain a flexible and strong economy, society and military into much of the 18th century. However, during a long period of peace from 1740 to 1768, the Ottoman military system fell behind those of its chief European rivals, the Habsburg and Russian empires. The Ottomans consequently suffered severe military defeats in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, culminating in the loss of both territory and global prestige. This prompted a comprehensive process of reform and modernization known as the Tanzimat; over the course of the 19th century, the Ottoman state became vastly more powerful and organized internally, despite suffering further territorial losses, especially in the Balkans, where a number of new states emerged.

Beginning in the late 19th century, various Ottoman intellectuals sought to further liberalize society and politics along European lines, culminating in the Young Turk Revolution of 1908 led by the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), which established the Second Constitutional Era and introduced competitive multi-party elections under a constitutional monarchy. However, following the disastrous Balkan Wars, the CUP became increasingly radicalized and nationalistic, leading a coup d'état in 1913 that established a one-party regime. The CUP allied the empire with Germany, hoping to escape from the diplomatic isolation that had contributed to its recent territorial losses; it thus joined World War I on the side of the Central Powers. While the empire was able to largely hold its own during the conflict, it struggled with internal dissent, especially the Arab Revolt. During this period, the Ottoman government engaged in genocide against Armenians, Assyrians, and Greeks.

In the aftermath of World War I, the victorious Allied Powers occupied and partitioned the Ottoman Empire, which lost its southern territories to the United Kingdom and France. The successful Turkish War of Independence, led by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk against the occupying Allies, led to the emergence of the Republic of Turkey in the Anatolian heartland and the abolition of the Ottoman monarchy in 1922, formally ending the Ottoman Empire.

Name

The word Ottoman is a historical anglicisation of the name of Osman I, the founder of the Empire and of the ruling House of Osman (also known as the Ottoman dynasty). Osman's name in turn was the Turkish form of the Arabic name ʿUthmān (عثمان). In Ottoman Turkish, the empire was referred to as Devlet-i ʿAlīye-yi ʿOsmānīye (دولت عليه عثمانیه), lit. 'Sublime Ottoman State', or simply Devlet-i ʿOsmānīye (دولت عثمانيه), lit. 'Ottoman State'.

The Turkish word for "Ottoman" (Osmanlı) originally referred to the tribal followers of Osman in the fourteenth century. The word subsequently came to be used to refer to the empire's military-administrative elite. In contrast, the term "Turk" (Türk) was used to refer to the Anatolian peasant and tribal population and was seen as a disparaging term when applied to urban, educated individuals.[28]: 26 [29] In the early modern period, an educated, urban-dwelling Turkish-speaker who was not a member of the military-administrative class typically referred to themselves neither as an Osmanlı nor as a Türk, but rather as a Rūmī (رومى), or "Roman", meaning an inhabitant of the territory of the former Byzantine Empire in the Balkans and Anatolia. The term Rūmī was also used to refer to Turkish speakers by the other Muslim peoples of the empire and beyond.[30]: 11 As applied to Ottoman Turkish-speakers, this term began to fall out of use at the end of the seventeenth century, and instead the word increasingly became associated with the Greek population of the empire, a meaning that it still bears in Turkey today.[31]: 51

In Western Europe, the names Ottoman Empire, Turkish Empire and Turkey were often used interchangeably, with Turkey being increasingly favoured both in formal and informal situations. This dichotomy was officially ended in 1920–1923, when the newly established Ankara-based Turkish government chose Turkey as the sole official name. At present, most scholarly historians avoid the terms "Turkey", "Turks", and "Turkish" when referring to the Ottomans, due to the empire's multinational character.[32]

History

| History of the Ottoman Empire |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

| Historiography (Ghaza, Decline) |

Rise (c. 1299–1453)

As the Rum Sultanate declined well into the 13th century, Anatolia was divided into a patchwork of independent Turkish principalities known as the Anatolian Beyliks. One of these beyliks, in the region of Bithynia on the frontier of the Byzantine Empire, was led by the Turkish[33] tribal leader Osman I (d. 1323/4),[34] a figure of obscure origins from whom the name Ottoman is derived.[35]: 444 Osman's early followers consisted both of Turkish tribal groups and Byzantine renegades, with many but not all converts to Islam.[36]: 59 [37]: 127 Osman extended the control of his principality by conquering Byzantine towns along the Sakarya River. A Byzantine defeat at the Battle of Bapheus in 1302 contributed to Osman's rise as well. It is not well understood how the early Ottomans came to dominate their neighbors, due to the lack of sources surviving from this period. The Ghaza thesis popular during the twentieth century credited their success to their rallying of religious warriors to fight for them in the name of Islam, but it is no longer generally accepted. No other hypothesis has attracted broad acceptance.[38]: 5, 10 [39]: 104

In the century after the death of Osman I, Ottoman rule had begun to extend over Anatolia and the Balkans. The earliest conflicts began during the Byzantine–Ottoman wars, waged in Anatolia in the late 13th century before entering Europe in the mid-14th century, followed by the Bulgarian–Ottoman wars and the Serbian–Ottoman wars waged beginning in the mid 14th century. Much of this period was characterised by Ottoman expansion into the Balkans. Osman's son, Orhan, captured the northwestern Anatolian city of Bursa in 1326, making it the new capital of the Ottoman state and supplanting Byzantine control in the region. The important port city of Thessaloniki was captured from the Venetians in 1387 and sacked. The Ottoman victory in Kosovo in 1389 effectively marked the end of Serbian power in the region, paving the way for Ottoman expansion into Europe.[40]: 95–96 The Battle of Nicopolis for the Bulgarian Tsardom of Vidin in 1396, widely regarded as the last large-scale crusade of the Middle Ages, failed to stop the advance of the victorious Ottoman Turks.[41]

As the Turks expanded into the Balkans, the conquest of Constantinople became a crucial objective. The Ottomans had already wrested control of nearly all former Byzantine lands surrounding the city, but the strong defense of Constantinople's strategic position on the Bosporus Strait made it difficult to conquer. In 1402, the Byzantines were temporarily relieved when the Turco-Mongol leader Timur, founder of the Timurid Empire, invaded Ottoman Anatolia from the east. In the Battle of Ankara in 1402, Timur defeated the Ottoman forces and took Sultan Bayezid I as a prisoner, throwing the empire into disorder. The ensuing civil war, also known as the Fetret Devri, lasted from 1402 to 1413 as Bayezid's sons fought over succession. It ended when Mehmed I emerged as the sultan and restored Ottoman power.[42]: 363

The Balkan territories lost by the Ottomans after 1402, including Thessaloniki, Macedonia, and Kosovo, were later recovered by Murad II between the 1430s and 1450s. On 10 November 1444, Murad repelled the Crusade of Varna by defeating the Hungarian, Polish, and Wallachian armies under Władysław III of Poland (also King of Hungary) and John Hunyadi at the Battle of Varna, although Albanians under Skanderbeg continued to resist. Four years later, John Hunyadi prepared another army of Hungarian and Wallachian forces to attack the Turks, but was again defeated at the Second Battle of Kosovo in 1448.[43]: 29

According to modern historiography, there is a direct connection between the fast Ottoman military advance and the consequences of the Black Death from the mid-fourteenth century onwards. Byzantine territories, where the initial Ottoman conquests were carried out, were exhausted demographically and militarily due to the plague outbreaks, which facilitated the Ottoman expansion. In addition, the slave hunting — executed at first by akinci irregulars expediting before the Ottoman army — was the main economic driving force behind the Ottoman conquest. Some 21st-century authors re-periodize the Ottoman conquest of the Balkans into the akıncı phase, which spanned 8 to 13 decades, characterized by continuous slave hunting and destruction, followed by the phase of administrative integration into the Ottoman Empire.[44][45][46] where the bubonic plague pandemic occurred between 1347 and 1349.[45][46][47]

Expansion and peak (1453–1566)

The son of Murad II, Mehmed the Conqueror, reorganized both state and military, and on 29 May 1453 conquered Constantinople, ending the Byzantine Empire.[48] Mehmed allowed the Eastern Orthodox Church to maintain its autonomy and land in exchange for accepting Ottoman authority.[49] Due to tension between the states of western Europe and the later Byzantine Empire, the majority of the Orthodox population accepted Ottoman rule as preferable to Venetian rule.[49] Albanian resistance was a major obstacle to Ottoman expansion on the Italian peninsula.[50]

In the 15th and 16th centuries, the Ottoman Empire entered a period of expansion. The Empire prospered under the rule of a line of committed and effective Sultans. It also flourished economically due to its control of the major overland trade routes between Europe and Asia.[51]: 111 [m]

Sultan Selim I (1512–1520) dramatically expanded the Empire's eastern and southern frontiers by defeating Shah Ismail of Safavid Iran, in the Battle of Chaldiran.[52]: 91–105 Selim I established Ottoman rule in Egypt by defeating and annexing the Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt and created a naval presence on the Red Sea. After this Ottoman expansion, competition began between the Portuguese Empire and the Ottoman Empire to become the dominant power in the region.[53]: 55–76

Suleiman the Magnificent (1520–1566)[54] captured Belgrade in 1521, conquered the southern and central parts of the Kingdom of Hungary as part of the Ottoman–Hungarian Wars, and, after his historic victory in the Battle of Mohács in 1526, he established Ottoman rule in the territory of present-day Hungary (except the western part) and other Central European territories. He then laid siege to Vienna in 1529, but failed to take the city.[55]: 50 In 1532, he made another attack on Vienna, but was repulsed in the siege of Güns.[56][57] Transylvania, Wallachia and, intermittently, Moldavia, became tributary principalities of the Ottoman Empire. In the east, the Ottoman Turks took Baghdad from the Persians in 1535, gaining control of Mesopotamia and naval access to the Persian Gulf. In 1555, the Caucasus became officially partitioned for the first time between the Safavids and the Ottomans, a status quo that remained until the end of the Russo-Turkish War (1768–1774). By this partitioning of the Caucasus as signed in the Peace of Amasya, Western Armenia, western Kurdistan, and Western Georgia (including western Samtskhe) fell into Ottoman hands,[58] while southern Dagestan, Eastern Armenia, Eastern Georgia, and Azerbaijan remained Persian.[59]

In 1539, a 60,000-strong Ottoman army besieged the Spanish garrison of Castelnuovo on the Adriatic coast; the successful siege cost the Ottomans 8,000 casualties,[61] but Venice agreed to terms in 1540, surrendering most of its empire in the Aegean and the Morea. France and the Ottoman Empire, united by mutual opposition to Habsburg rule,[62] became strong allies. The French conquests of Nice (1543) and Corsica (1553) occurred as a joint venture between the forces of the French king Francis I and Suleiman, and were commanded by the Ottoman admirals Hayreddin Barbarossa and Dragut.[63] A month before the siege of Nice, France supported the Ottomans with an artillery unit during the 1543 Ottoman conquest of Esztergom in northern Hungary. After further advances by the Turks, the Habsburg ruler Ferdinand officially recognized Ottoman ascendancy in Hungary in 1547. Suleiman I died of natural causes in his tent during the siege of Szigetvár in 1566. Following his death, the Ottomans were said to be declining, although this has been rejected by many scholars.[64]

By the end of Suleiman's reign, the Empire spanned approximately 877,888 sq mi (2,273,720 km2), extending over three continents.[65]: 545

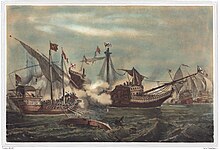

In addition, the Empire became a dominant naval force, controlling much of the Mediterranean Sea.[66]: 61 By this time, the Ottoman Empire was a major part of the European political sphere. The Ottomans became involved in multi-continental religious wars when Spain and Portugal were united under the Iberian Union. The Ottomans were holders of the Caliph title, meaning they were the leaders of all Muslims worldwide. The Iberians were leaders of the Christian crusaders, and so the two were locked in a worldwide conflict. There were zones of operations in the Mediterranean Sea[67] and Indian Ocean,[68] where Iberians circumnavigated Africa to reach India and, on their way, wage war upon the Ottomans and their local Muslim allies. Likewise, the Iberians passed through newly-Christianized Latin America and had sent expeditions that traversed the Pacific in order to Christianize the formerly Muslim Philippines and use it as a base to further attack the Muslims in the Far East.[69] In this case, the Ottomans sent armies to aid its easternmost vassal and territory, the Sultanate of Aceh in Southeast Asia.[70]: 84 [71]

During the 1600s, the worldwide conflict between the Ottoman Caliphate and Iberian Union was a stalemate since both powers were at similar population, technology and economic levels. Nevertheless, the success of the Ottoman political and military establishment was compared to the Roman Empire, despite the difference in the size of their respective territories, by the likes of the contemporary Italian scholar Francesco Sansovino and the French political philosopher Jean Bodin.[72]

Stagnation and reform (1566–1827)

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Ottoman_EmpireText je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk