A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

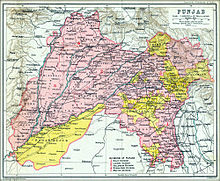

Punjab (/pʌnˈdʒɑːb/ ;[8] Punjabi: [pənˈdʒɑːb] ), historically known as Panchanada (Sanskrit) or Pentapotamia, is a state in northwestern India. Forming part of the larger Punjab region of the Indian subcontinent, the state is bordered by the Indian states of Himachal Pradesh to the north and northeast, Haryana to the south and southeast, and Rajasthan to the southwest; by the Indian union territories of Chandigarh to the east and Jammu and Kashmir to the north. It shares an international border with Punjab, a province of Pakistan to the west.[9] The state covers an area of 50,362 square kilometres (19,445 square miles), which is 1.53% of India's total geographical area,[10] making it the 19th-largest Indian state by area out of 28 Indian states (20th largest, if Union Territories are considered). With over 27 million inhabitants, Punjab is the 16th-largest Indian state by population, comprising 23 districts.[2] Punjabi, written in the Gurmukhi script, is the most widely spoken and the official language of the state.[11] The main ethnic group are the Punjabis, with Sikhs (57.7%) and Hindus (38.5%) forming the dominant religious groups.[12] The state capital, Chandigarh, is a union territory and also the capital of the neighbouring state of Haryana. Three tributaries of the Indus River — the Sutlej, Beas, and Ravi — flow through Punjab.[13]

The history of Punjab has witnessed the migration and settlement of different tribes of people with different cultures and ideas, forming a civilisational melting pot. The ancient Indus Valley civilisation flourished in the region until its decline around 1900 BCE.[14] Punjab was enriched during the height of the Vedic period, but declined in predominance with the rise of the Mahajanapadas.[15] The region formed the frontier of initial empires during antiquity including Alexander's and the Maurya empires.[16][17] It was subsequently conquered by the Kushan Empire, Gupta Empire,[18] and then Harsha's Empire.[19] Punjab continued to be settled by nomadic people; including the Huna, Turkic and the Mongols. Punjab came under Muslim rule c. 1000 CE,[20] and was part of the Delhi Sultanate and the Mughal Empire.[21] Sikhism, based on the teachings of Sikh Gurus, emerged between the 15th and 17th centuries. Conflicts between the Mughals and the later Sikh Gurus precipitated a militarisation of the Sikhs, resulting in the formation of a confederacy after the weakening of the Mughal Empire, which competed for control with the larger Durrani Empire.[22] This confederacy was united in 1801 by Maharaja Ranjit Singh, forming the Sikh Empire.[23]

The larger Punjab region was annexed by the British East India Company from the Sikh Empire in 1849.[24] At the time of the independence of India from British rule in 1947, the Punjab province was partitioned along religious lines amidst widespread violence, with the Muslim-majority western portion becoming part of Pakistan and the Hindu- and Sikh-majority east remaining in India, causing a large-scale migration between the two.[25] After the Punjabi Suba movement, Indian Punjab was reorganised on the basis of language in 1966,[26] when its Haryanvi- and Hindi-speaking areas were carved out as Haryana, Pahari-speaking regions attached to Himachal Pradesh and the remaining, mostly Punjabi-speaking areas became the current state of Punjab. A separatist insurgency occurred in the state during the 1980s.[27] At present, the economy of Punjab is the 15th-largest state economy in India with ₹8.02 trillion (equivalent to ₹8.0 trillion or US$100 billion in 2023) in gross domestic product and a per capita GDP of ₹264,000 (equivalent to ₹260,000 or US$3,300 in 2023), ranking 17th among Indian states.[4] Since independence, Punjab is predominantly an agrarian society. It is the ninth-highest ranking among Indian states in human development index.[5] Punjab has bustling tourism, music, culinary, and film industries.[28]

Etymology

History

Ancient period

The Punjab region is noted as the site of one of the earliest urban societies, the Indus Valley Civilisation that flourished from about 3000 B.C. and declined rapidly 1,000 years later, following the Indo-Aryan migrations that overran the region in waves between 1500 and 500 B.C.[29] Frequent intertribal wars stimulated the growth of larger groupings ruled by chieftains and kings, who ruled local kingdoms known as Mahajanapadas.[29] The rise of kingdoms and dynasties in Punjab is chronicled in the ancient Hindu epics, particularly the Mahabharata.[29] The epic battles described in the Mahabharata are chronicled as being fought in what is now the state of Haryana and historic Punjab. The Gandharas, Kambojas, Trigartas, Andhra, Pauravas, Bahlikas (Bactrian settlers of the Punjab), Yaudheyas, and others sided with the Kauravas in the great battle fought at Kurukshetra.[30] According to Dr Fauja Singh and Dr. L. M. Joshi: "There is no doubt that the Kambojas, Daradas, Kaikayas, Andhra, Pauravas, Yaudheyas, Malavas, Saindhavas, and Kurus had jointly contributed to the heroic tradition and composite culture of ancient Punjab."[31] The bulk of the Rigveda was composed in the Punjab region between circa 1500 and 1200 BC,[32] while later Vedic scriptures were composed more eastwards, between the Yamuna and Ganges rivers. The historical Vedic religion constituted the religious ideas and practices in Punjab during the Vedic period (1500–500 BCE), centred primarily in the worship of Indra.[33][34][35][i]

The earliest known notable local king of this region was known as King Porus, who fought the famous Battle of the Hydaspes against Alexander the Great. His kingdom spanned between rivers Hydaspes (Jhelum) and Acesines (Chenab); Strabo had held the territory to contain almost 300 cities.[36] He (alongside Abisares) had a hostile relationship with the Kingdom of Taxila which was ruled by his extended family.[36] When the armies of Alexander crossed Indus in its eastward migration, probably in Udabhandapura, he was greeted by the-then ruler of Taxila, Omphis.[36] Omphis had hoped to force both Porus and Abisares into submission leveraging the might of Alexander's forces and diplomatic missions were mounted, but while Abisares accepted the submission, Porus refused.[36] This led Alexander to seek a face-off with Porus.[36] Thus began the Battle of the Hydaspes in 326 BC; the exact site remains unknown.[36] The battle is thought to have resulted in a decisive Greek victory; however, A. B. Bosworth warns against an uncritical reading of Greek sources who were obviously exaggerative.[36]

Alexander later founded two cities—Nicaea at the site of victory and Bucephalous at the battle-ground, in memory of his horse, who died soon after the battle.[36][a] Later, tetradrachms would be minted depicting Alexander on horseback, armed with a sarissa and attacking a pair of Indians on an elephant.[36][37] Porus refused to surrender and wandered about atop an elephant, until he was wounded and his force routed.[36] When asked by Alexander how he wished to be treated, Porus replied "Treat me as a king would treat another king".[38] Despite the apparently one-sided results, Alexander was impressed by Porus and chose to not depose him.[39][40][41] Not only was his territory reinstated but also expanded with Alexander's forces annexing the territories of Glausaes, who ruled the area northeast of Porus' kingdom.[39]

After Alexander's death in 323 BCE, Perdiccas became the regent of his empire, and after Perdiccas's murder in 321 BCE, Antipater became the new regent.[42] According to Diodorus, Antipater recognised Porus's authority over the territories along the Indus River. However, Eudemus, who had served as Alexander's satrap in the Punjab region, treacherously killed Porus.[43] The battle is historically significant because it resulted in the syncretism of ancient Greek political and cultural influences to the Indian subcontinent, yielding works such as Greco-Buddhist art, which continued to have an impact for the ensuing centuries. The region was then divided between the Maurya Empire and the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom in 302 B.C.E. Menander I Soter conquered Punjab and made Sagala (present-day Sialkot) the capital of the Indo-Greek Kingdom.[44][45] Menander is noted for having become a patron and convert to Greco-Buddhism and he is widely regarded as the greatest of the Indo-Greek kings.[46] Greek influence in the region ended around 12 B.C.E. when the Punjab fell under the Sasanians.

Medieval period

Following the muslim conquests in the Indian subcontinent at the beginning of the 8th century, Arab armies of the Umayyad Caliphate penetrated into South Asia introducing Islam into Punjab.[47][48] In the ninth century, the Hindu Shahi dynasty emerged in the Punjab, ruling much of Punjab and eastern Afghanistan.[29] The Turkic Ghaznavids in the tenth century overthrew the Hindu Shahis and consequently ruled for 157 years, gradually declining as a power until the Ghurid conquest of Lahore by Muhammad of Ghor in 1186, deposing the last Ghaznavid ruler Khusrau Malik.[49] Following the death of Muhammad of Ghor in 1206, the Ghurid state fragmented and was replaced in northern India by the Delhi Sultanate. The Delhi Sultanate ruled the Punjab for the next three hundred years, led by five unrelated dynasties, the Mamluks, Khalajis, Tughlaqs, Sayyids and Lodis. A significant event in the late 15th century Punjab was the formation of Sikhism by Guru Nanak.[ii][50][51] The history of the Sikh faith is closely associated with the history of Punjab and the socio-political situation in the north-west of the Indian subcontinent in the 17th century.[52][53][54][55]

The hymns composed by Guru Nanak were later collected in the Guru Granth Sahib, the central religious scripture of the Sikhs.[56] The religion developed and evolved in times of religious persecution, gaining converts from both Hinduism and Islam.[57] Mughal rulers of India tortured and executed two of the Sikh gurus—Guru Arjan (1563–1605) and Guru Tegh Bahadur (1621–1675)—after they refused to convert to Islam.[58][59][60][61][62] The persecution of Sikhs triggered the founding of the Khalsa by Guru Gobind Singh in 1699 as an order to protect the freedom of conscience and religion,[58][63] with members expressing the qualities of a Sant-Sipāhī ('saint-soldier').[64][65] The lifetime of Guru Nanak coincided with the conquest of northern India by Babur and establishment of the Mughal Empire. Jahangir ordered the execution of Guru Arjun Dev, while in Mughal custody, for supporting his son Khusrau Mirza's rival claim to the throne.[66] Guru Arjan Dev's death led to the sixth Guru Guru Hargobind to declare sovereignty in the creation of the Akal Takht and the establishment of a fort to defend Amritsar. Jahangir then jailed Guru Hargobind at Gwalior, but released him after a number of years when he no longer felt threatened. The succeeding son of Jahangir, Shah Jahan, took offence at Guru Hargobind's declaration and after a series of assaults on Amritsar, forced the Sikhs to retreat to the Sivalik Hills.[67] The ninth Guru, Guru Tegh Bahadur, moved the Sikh community to Anandpur and travelled extensively to visit and preach in defiance of Aurangzeb, who attempted to install Ram Rai as new guru.

Modern period

The Mughals came to power in the early sixteenth century and gradually expanded to control all of the Punjab from their capital at Lahore. As Mughal power weakened, Afghan rulers took control of the region.[29] Contested by Marathas and Afghans, the region was the center of the growing influence of the Sikhs, who expanded and established the Sikh Empire in 1799 as the Mughals and Afghans weakened.[68] The Cis-Sutlej states were a group of states in modern Punjab and Haryana states lying between the Sutlej River on the north, the Himalayas on the east, the Yamuna River and Delhi District on the south, and Sirsa district on the west. These states were ruled by the Sikh Confederacy.[69] The empire existed from 1799, when Ranjit Singh captured Lahore, to 1849, when it was defeated and conquered in the Second Anglo-Sikh War. It was forged on the foundations of the Khalsa from a collection of autonomous Sikh misls.[70][71] At its peak in the 19th century, the Empire extended from the Khyber Pass in the west to western Tibet in the east, and from Mithankot in the south to Kashmir in the north. It was divided into four provinces: Lahore, in Punjab, which became the Sikh capital; Multan, also in Punjab; Peshawar; and Kashmir from 1799 to 1849. Religiously diverse, with an estimated population of 3.5 million in 1831 (making it the 19th most populous country at the time),[72] it was the last major region of the Indian subcontinent to be annexed by the British Empire. The Sikh Empire spanned a total of over 200,000 sq mi (520,000 km2) at its zenith.[73][74][75]

After Ranjit Singh's death in 1839, the empire was severely weakened by internal divisions and political mismanagement. This opportunity was used by the East India Company to launch the First and Second Anglo-Sikh Wars. The country was finally annexed and dissolved at the end of the Second Anglo-Sikh War in 1849 into separate princely states and the province of Punjab. Eventually, a Lieutenant Governorship was established in Lahore as a direct representative of the Crown.[76]: 221

Colonial era

The Punjab was annexed by the East India Company in 1849. Although nominally part of the Bengal Presidency it was administratively independent. During the Indian Rebellion of 1857, apart from Revolt led by Ahmed Khan Kharal and Murree rebellion of 1857, the Punjab remained relatively peaceful.[77] In 1858, under the terms of the Queen's Proclamation issued by Queen Victoria, the Punjab came under the direct rule of Britain. Colonial rule had a profound impact on all areas of Punjabi life. Economically it transformed the Punjab into the richest farming area of India, socially it sustained the power of large landowners and politically it encouraged cross-communal co-operation among land owning groups.[78] The Punjab also became the major centre of recruitment into the Indian Army. By patronising influential local allies and focusing administrative, economic and constitutional policies on the rural population, the British ensured the loyalty of its large rural population.[78] Administratively, colonial rule instated a system of bureaucracy and measure of the law. The 'paternal' system of the ruling elite was replaced by 'machine rule' with a system of laws, codes, and procedures. For purposes of control, the British established new forms of communication and transportation, including post systems, railways, roads, and telegraphs. The creation of Canal Colonies in western Punjab between 1860 and 1947 brought 14 million acres of land under cultivation, and revolutionised agricultural practices in the region.[78] To the agrarian and commercial class was added a professional middle class that had risen the social ladder through the use of the English education, which opened up new professions in law, government, and medicine.[79] Despite these developments, colonial rule was marked by exploitation of resources. For the purpose of exports, the majority of external trade was controlled by British export banks. The Imperial government exercised control over the finances of Punjab and took the majority of the income for itself.[80]

In 1919, Reginald Dyer ordered his troops to fire on a crowd of demonstrators, mostly Sikhs in Amritsar. The Jallianwala massacre fuelled the Indian independence movement.[29] Nationalists declared the independence of India from Lahore in 1930 but were quickly suppressed.[29] The struggle for Indian independence witnessed competing and conflicting interests in the Punjab. When the Second World War broke out, nationalism in British India had already divided into religious movements.[29] The landed elites of the Muslim, Hindu and Sikh communities had loyally collaborated with the British since annexation, supported the Unionist Party and were hostile to the Congress party led independence movement.[81] Amongst the peasantry and urban middle classes, the Hindus were the most active National Congress supporters, the Sikhs flocked to the Akali movement while the Muslims eventually supported the Muslim League.[81] Many Sikhs and other minorities supported the Hindus, who promised a secular multicultural and multireligious society. In March 1940, the All-India Muslim League passed the Lahore Resolution, demanding the creation of a separate state from Muslim majority areas in British India. This triggered bitter protests by the Hindus and Sikhs in Punjab, who could not accept living in a Muslim Islamic state.[82]

After the partition of the subcontinent had been decided, special meetings of the Western and Eastern Section of the Legislative Assembly were held on 23 June 1947 to decide whether or not the Province of the Punjab be partitioned. After voting on both sides, partition was decided and the existing Punjab Legislative Assembly was also divided into West Punjab Legislative Assembly and the East Punjab Legislative Assembly. This last Assembly before independence, held its last sitting on 4 July 1947.[83] During this period, the British granted separate independence to India and Pakistan, setting off massive communal violence as Punjabi Muslims fled to Pakistan and Hindu and Sikh Punjabis fled east to India.[29] The Sikhs later demanded a Punjabi-speaking Punjab state with an autonomous Sikh government.[29]

Post-colonial era

During the colonial era, the various districts and princely states that made up Punjab Province were religiously eclectic, each containing significant populations of Punjabi Muslims, Punjabi Hindus, Punjabi Sikhs, Punjabi Christians, along with other ethnic and religious minorities. However, a major consequence of independence and the partition of Punjab Province in 1947 was the sudden shift towards religious homogeneity occurred in all districts across province and region owing to the new international border that cut through the subdivision.

The demographic shift was captured when comparing decadal census data taken in 1941 and 1951 respectively, and was primarily due to wide scale migration but also caused by large-scale religious cleansing riots which were witnessed across the region at the time. According to historical demographer Tim Dyson, in the eastern regions of Punjab that ultimately became Indian Punjab following independence, districts that were 66% Hindu in 1941 became 80% Hindu in 1951; those that were 20% Sikh became 50% Sikh in 1951. Conversely, in the western regions of Punjab that ultimately became Pakistani Punjab, all districts became almost exclusively Muslim by 1951.[84]

Following independence, several small Punjabi princely states, including Patiala, acceded to the Union of India and were united into the PEPSU. In 1956 this was integrated with the state of East Punjab to create a new, enlarged Indian state called simply "Punjab". Punjab Day is celebrated across the state on 1 November every year marking the formation of a Punjabi language speaking state under the Punjab Reorganisation Act (1966).[85][86]

In 1966, following Hindu and Sikh Punjabi demands, the Indian government divided Punjab into the state of Punjab and the Hindi majority-speaking states of Haryana and Himachal Pradesh.[29]

During the 1960s, Punjab was known for its prosperity within India, largely due to its fertile lands and industrious inhabitants. However, a significant portion of the Sikh community felt a sense of disparity from the central government of India. The roots of such grievances stretched back several decades, with the primary issue revolving around the distribution of water from the trio of rivers – Ravi, Beas, and Sutlej – that flowed across the Punjabi territory.[87]

Although Punjab had these waterways running across its lands, it was lawfully granted only a quarter of the water, precisely 24%, as per the Inter-State Water Disputes Act. The rest, a staggering 76%, was assigned to Rajasthan and Haryana. To many Punjabis, especially the farming community who heavily depended on these waters for irrigation, this allocation seemed inequitable. The water distribution was a significant contributing factor to the growing sense of disgruntlement against the central government.[87]

The seeds of discontent further sprouted with the advent of the Green Revolution during the 1960s. This initiative sought to boost agricultural output by introducing high-yield seed varieties, and enhancing the use of fertilisers and irrigation. In the midst of this transformative phase, Punjab became known as India's "food basket", contributing considerably to the nation's agricultural production. Yet, the financial profits garnered from this agricultural surge weren't fairly distributed.[88]

The majority of the gains were hoarded by landowners, who typically owned large plots and were best positioned to exploit the emerging technologies and farming practices. The working class and economically underprivileged segments of society, who often toiled as labourers on these farms, were left with only minor benefits. This uneven distribution of wealth conflicted sharply with Sikh religious customs, which preached economic justice and fair wealth distribution.[89]

The Green Revolution dealt a severe blow to Punjab's small farmers. The larger landowners, with their access to abundant resources and capital, were well-suited to adopt the agricultural innovations brought by the Revolution. This situation sparked further resentment among small farmers, many of whom were forced to relinquish their lands, unable to compete, thereby intensifying the economic chasm.[87]

Beyond the farming sector, Punjab lacked substantial employment opportunities. An excessive focus on agriculture resulted in the state's industrial sector's neglect, leaving it notably underdeveloped. This skewed concentration on agriculture meant that many economically challenged peasants, without feasible employment alternatives, felt cornered and disgruntled.[88]

Even the affluent landowners, the initial beneficiaries of the Green Revolution, felt the economic pinch due to soaring prices of farming inputs like fertilisers and pesticides, and the dearth of essential resources like electricity and water.[89]

Although the Green Revolution was primarily conceived to amplify productivity, it couldn't sustain this increased output over a prolonged period. The introduction of novel crop varieties led to a decline in genetic diversity, thus introducing a new ecological risk. Furthermore, these new crops demanded more water and were highly dependent on chemical fertilisers, both of which had deleterious environmental consequences. Overuse of water led to groundwater resource depletion, and heavy chemical usage adversely affected soil and water systems, further undermining long-term productivity.[87]

From 1981 to 1995 the state suffered a 14-year-long insurgency. Problems began due to disputes between Punjabi Sikhs and the central government of the Republic of India. Tensions escalated throughout the early 1980s and eventually culminated with Operation Blue Star in 1984; an Indian Army operation aimed at the dissident Sikh community of Punjab. Shortly thereafter, Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi was assassinated by two of her Sikh bodyguards. The decade that followed was noted for widespread inter-communal violence and accusations of genocide on the part of the Sikh community by the Indian government.[90]

Geography

Punjab is in northwestern India and has a total area of 50,362 square kilometres (19,445 sq mi). Punjab is bordered by Pakistan's Punjab province on the west, Jammu and Kashmir on the north, Himachal Pradesh on the northeast and Haryana and Rajasthan on the south.[9] Most of Punjab lies in a fertile, alluvial plain with perennial rivers and an extensive irrigation canal system.[91] A belt of undulating hills extends along the northeastern part of the state at the foot of the Himalayas. Its average elevation is 300 metres (980 ft) above sea level, with a range from 180 metres (590 ft) in the southwest to more than 500 metres (1,600 ft) around the northeast border. The southwest of the state is semi-arid, eventually merging into the Thar Desert. Of the five Punjab rivers, three—Sutlej, Beas and Ravi—flow through the Indian state. The Sutlej and Ravi define parts of the international border with Pakistan.

The soil characteristics are influenced to a limited extent by the topography, vegetation and parent rock. The variation in soil profile characteristics are much more pronounced because of the regional climatic differences.[92] Punjab is divided into three distinct regions on the basis of soil types: southwestern, central, and eastern. Punjab falls under seismic zones II, III, and IV. Zone II is considered a low-damage risk zone; zone III is considered a moderate-damage risk zone; and zone IV is considered a high-damage risk zone.[93]

Climate

The geography and subtropical latitudinal location of Punjab lead to large variations in temperature from month to month. Even though only limited regions experience temperatures below 0 °C (32 °F), ground frost is commonly found in the majority of Punjab during the winter season. The temperature rises gradually with high humidity and overcast skies. However, the rise in temperature is steep when the sky is clear and humidity is low.[94]

The maximum temperatures usually occur in mid-May and June. The temperature remains above 40 °C (104 °F) in the entire region during this period. Ludhiana recorded the highest maximum temperature at 46.1 °C (115.0 °F) with Patiala and Amritsar recording 45.5 °C (113.9 °F). The maximum temperature during the summer in Ludhiana remains above 41 °C (106 °F) for a duration of one and a half months. These areas experience the lowest temperatures in January. The sun rays are oblique during these months and the cold winds control the temperature at daytime.[94]

Punjab experiences its minimum temperature from December to February. The lowest temperature was recorded at Amritsar (0.2 °C (32.4 °F)) and Ludhiana stood second with 0.5 °C (32.9 °F). The minimum temperature of the region remains below 5 °C (41 °F) for almost two months during the winter season. The highest minimum temperature of these regions in June is more than the daytime maximum temperatures experienced in January and February. Ludhiana experiences minimum temperatures above 27 °C (81 °F) for more than two months. The annual average temperature in the entire state is approximately 21 °C (70 °F). Further, the mean monthly temperature range varies between 9 °C (48 °F) in July to approximately 18 °C (64 °F) in November.[94]

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Record high °C (°F) | 26.8 (80.2) |

32.2 (90.0) |

36.2 (97.2) |

44.1 (111.4) |

48.0 (118.4) |

47.8 (118.0) |

45.6 (114.1) |

40.7 (105.3) |

40.6 (105.1) |

38.3 (100.9) |

34.2 (93.6) |

28.5 (83.3) |

48.0 (118.4) |

| Mean maximum °C (°F) | 22.7 (72.9) |

26.1 (79.0) |

32.4 (90.3) |

40.6 (105.1) |

44.5 (112.1) |

44.6 (112.3) |

39.8 (103.6) |

37.0 (98.6) |

36.4 (97.5) |

35.3 (95.5) |

30.4 (86.7) |

25.2 (77.4) |

45.6 (114.1) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 17.7 (63.9) |

21.7 (71.1) |

27.0 (80.6) |

34.4 (93.9) |

39.4 (102.9) |

38.9 (102.0) |

35.0 (95.0) |

34.1 (93.4) |

33.9 (93.0) |

32.0 (89.6) |

27.0 (80.6) |

20.9 (69.6) |

30.1 (86.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 11.0 (51.8) |

14.4 (57.9) |

19.0 (66.2) |

25.4 (77.7) |

30.7 (87.3) |

31.8 (89.2) |

30.3 (86.5) |

29.7 (85.5) |

28.2 (82.8) |

24.1 (75.4) |

18.1 (64.6) |

12.6 (54.7) |

22.9 (73.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 3.8 (38.8) |

6.7 (44.1) |

11.2 (52.2) |

16.6 (61.9) |

21.9 (71.4) |

24.7 (76.5) |

25.7 (78.3) |

25.3 (77.5) |

22.7 (72.9) |

16.4 (61.5) |

9.4 (48.9) Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Punjab_(India) Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Analytika

Antropológia Aplikované vedy Bibliometria Dejiny vedy Encyklopédie Filozofia vedy Forenzné vedy Humanitné vedy Knižničná veda Kryogenika Kryptológia Kulturológia Literárna veda Medzidisciplinárne oblasti Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy Metavedy Metodika Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok. www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk | ||