A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Part of a series on |

| Mahāyāna Buddhism |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Buddhism |

|---|

|

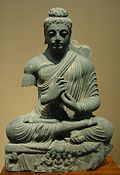

Mahāyāna (/ˌmɑːhəˈjɑːnə/ MAH-hə-YAH-nə; Sanskrit: महायान, pronounced [mɐɦaːˈjaːnɐ], lit. 'Great Vehicle') is a term for a broad group of Buddhist traditions, texts, philosophies, and practices developed in ancient India (c. 1st century BCE onwards). It is considered one of the three main existing branches of Buddhism, the others being Theravāda and Vajrayāna.[1] Mahāyāna accepts the main scriptures and teachings of early Buddhism but also recognizes various doctrines and texts that are not accepted by Theravada Buddhism as original. These include the Mahāyāna sūtras and their emphasis on the bodhisattva path and Prajñāpāramitā.[2] Vajrayāna or Mantra traditions are a subset of Mahāyāna which makes use of numerous tantric methods Vajrayānists consider to help achieve Buddhahood.[1]

Mahāyāna also refers to the path of the bodhisattva striving to become a fully awakened Buddha for the benefit of all sentient beings, and is thus also called the "Bodhisattva Vehicle" (Bodhisattvayāna).[3][note 1] Mahāyāna Buddhism generally sees the goal of becoming a Buddha through the bodhisattva path as being available to all and sees the state of the arhat as incomplete.[4] Mahāyāna also includes numerous Buddhas and bodhisattvas that are not found in Theravada (such as Amitābha and Vairocana).[5] Mahāyāna Buddhist philosophy also promotes unique theories, such as the Madhyamaka theory of emptiness (śūnyatā), the Vijñānavāda ("the doctrine of consciousness" also called "mind-only"), and the Buddha-nature teaching.

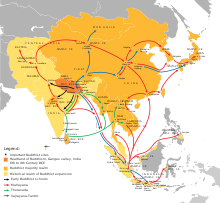

While initially a small movement in India, Mahāyāna eventually grew to become an influential force in Indian Buddhism.[6] Large scholastic centers associated with Mahāyāna such as Nalanda and Vikramashila thrived between the 7th and 12th centuries.[6] In the course of its history, Mahāyāna Buddhism spread from South Asia to East Asia, Southeast Asia and the Himalayan regions. Various Mahāyāna traditions are the predominant forms of Buddhism found in China, Korea, Japan, Taiwan, Singapore, Vietnam, Philippines, Indonesia and Malaysia.[7] Since Vajrayāna is a tantric form of Mahāyāna, Mahāyāna Buddhism is also dominant in Tibet, Mongolia, Bhutan, and other Himalayan regions. It has also been traditionally present elsewhere in Asia as a minority among Buddhist communities in Nepal, Malaysia, Indonesia and regions with Asian diaspora communities.

As of 2010, the Mahāyāna tradition was the largest major tradition of Buddhism, with 53% of Buddhists belonging to East Asian Mahāyāna and 6% to Vajrayāna, compared to 36% to Theravada.[8]

Etymology

Original Sanskrit

According to Jan Nattier, the term Mahāyāna ("Great Vehicle") was originally an honorary synonym for Bodhisattvayāna ("Bodhisattva Vehicle"),[9] the vehicle of a bodhisattva seeking buddhahood for the benefit of all sentient beings.[3] The term Mahāyāna (which had earlier been used simply as an epithet for Buddhism itself) was therefore adopted at an early date as a synonym for the path and the teachings of the bodhisattvas. Since it was simply an honorary term for Bodhisattvayāna, the adoption of the term Mahāyāna and its application to Bodhisattvayāna did not represent a significant turning point in the development of a Mahāyāna tradition.[9]

The earliest Mahāyāna texts, such as the Lotus Sūtra, often use the term Mahāyāna as a synonym for Bodhisattvayāna, but the term Hīnayāna is comparatively rare in the earliest sources. The presumed dichotomy between Mahāyāna and Hīnayāna can be deceptive, as the two terms were not actually formed in relation to one another in the same era.[10]

Among the earliest and most important references to Mahāyāna are those that occur in the Lotus Sūtra (Skt. Saddharma Puṇḍarīka Sūtra) dating between the 1st century BCE and the 1st century CE.[11] Seishi Karashima has suggested that the term first used in an earlier Gandhāri Prakrit version of the Lotus Sūtra was not the term mahāyāna but the Prakrit word mahājāna in the sense of mahājñāna (great knowing).[12][13] At a later stage when the early Prakrit word was converted into Sanskrit, this mahājāna, being phonetically ambivalent, may have been converted into mahāyāna, possibly because of what may have been a double meaning in the famous Parable of the Burning House, which talks of three vehicles or carts (Skt: yāna).[note 2][12][14]

Chinese translation

In Chinese, Mahāyāna is called 大乘 (dàshèng, or dàchéng), which is a calque of maha (great 大) yana (vehicle 乘). There is also the transliteration 摩诃衍那.[15][16] The term appeared in some of the earliest Mahāyāna texts, including Emperor Ling of Han's translation of the Lotus Sutra.[17] It also appears in the Chinese Āgamas, though scholars like Yin Shun argue that this is a later addition.[18][19][20] Some Chinese scholars also argue that the meaning of the term in these earlier texts is different from later ideas of Mahāyāna Buddhism.[21]

History

Origin

The origins of Mahāyāna are still not completely understood and there are numerous competing theories.[22] The earliest Western views of Mahāyāna assumed that it existed as a separate school in competition with the so-called "Hīnayāna" schools. Some of the major theories about the origins of Mahāyāna include the following:

The lay origins theory was first proposed by Jean Przyluski and then defended by Étienne Lamotte and Akira Hirakawa. This view states that laypersons were particularly important in the development of Mahāyāna and is partly based on some texts like the Vimalakirti Sūtra, which praise lay figures at the expense of monastics.[23] This theory is no longer widely accepted since numerous early Mahāyāna works promote monasticism and asceticism.[24][25]

The Mahāsāṃghika origin theory, which argues that Mahāyāna developed within the Mahāsāṃghika tradition.[24] This is defended by scholars such as Hendrik Kern, A.K. Warder and Paul Williams who argue that at least some Mahāyāna elements developed among Mahāsāṃghika communities (from the 1st century BCE onwards), possibly in the area along the Kṛṣṇa River in the Āndhra region of southern India.[26][27][28][29] The Mahāsāṃghika doctrine of the supramundane (lokottara) nature of the Buddha is sometimes seen as a precursor to Mahāyāna views of the Buddha.[5] Some scholars also see Mahāyāna figures like Nāgārjuna, Dignaga, Candrakīrti, Āryadeva, and Bhavaviveka as having ties to the Mahāsāṃghika tradition of Āndhra.[30] However, other scholars have also pointed to different regions as being important, such as Gandhara and northwest India.[31][note 3][32]

The Mahāsāṃghika origins theory has also slowly been shown to be problematic by scholarship that revealed how certain Mahāyāna sutras show traces of having developed among other nikāyas or monastic orders (such as the Dharmaguptaka).[33] Because of such evidence, scholars like Paul Harrison and Paul Williams argue that the movement was not sectarian and was possibly pan-buddhist.[24][34] There is no evidence that Mahāyāna ever referred to a separate formal school or sect of Buddhism, but rather that it existed as a certain set of ideals, and later doctrines, for aspiring bodhisattvas.[17]

The "forest hypothesis" meanwhile states that Mahāyāna arose mainly among "hard-core ascetics, members of the forest dwelling (aranyavasin) wing of the Buddhist Order", who were attempting to imitate the Buddha's forest living.[35] This has been defended by Paul Harrison, Jan Nattier and Reginald Ray. This theory is based on certain sutras like the Ugraparipṛcchā Sūtra and the Mahāyāna Rāṣṭrapālapaṛiprcchā which promote ascetic practice in the wilderness as a superior and elite path. These texts criticize monks who live in cities and denigrate the forest life.[17][36]

Jan Nattier's study of the Ugraparipṛcchā Sūtra, A few good men (2003) argues that this sutra represents the earliest form of Mahāyāna, which presents the bodhisattva path as a 'supremely difficult enterprise' of elite monastic forest asceticism.[24] Boucher's study on the Rāṣṭrapālaparipṛcchā-sūtra (2008) is another recent work on this subject.[37]

The cult of the book theory, defended by Gregory Schopen, states that Mahāyāna arose among a number of loosely connected book worshiping groups of monastics, who studied, memorized, copied and revered particular Mahāyāna sūtras. Schopen thinks they were inspired by cult shrines where Mahāyāna sutras were kept.[24] Schopen also argued that these groups mostly rejected stupa worship, or worshiping holy relics.

David Drewes has recently argued against all of the major theories outlined above. He points out that there is no actual evidence for the existence of book shrines, that the practice of sutra veneration was pan-Buddhist and not distinctly Mahāyāna. Furthermore, Drewes argues that "Mahāyāna sutras advocate mnemic/oral/aural practices more frequently than they do written ones."[24] Regarding the forest hypothesis, he points out that only a few Mahāyāna sutras directly advocate forest dwelling, while the others either do not mention it or see it as unhelpful, promoting easier practices such as "merely listening to the sutra, or thinking of particular Buddhas, that they claim can enable one to be reborn in special, luxurious 'pure lands' where one will be able to make easy and rapid progress on the bodhisattva path and attain Buddhahood after as little as one lifetime."[24]

Drewes states that the evidence merely shows that "Mahāyāna was primarily a textual movement, focused on the revelation, preaching, and dissemination of Mahāyāna sutras, that developed within, and never really departed from, traditional Buddhist social and institutional structures."[38] Drewes points out the importance of dharmabhanakas (preachers, reciters of these sutras) in the early Mahāyāna sutras. This figure is widely praised as someone who should be respected, obeyed ('as a slave serves his lord'), and donated to, and it is thus possible these people were the primary agents of the Mahāyāna movement.[38]

Early Mahayana came directly from "early Buddhist schools" and was a successor to them.[39][40]

Early Mahāyāna

"Bu-ddha-sya A-mi-tā-bha-sya"

"Of the Buddha Amitabha"[42]

The earliest textual evidence of "Mahāyāna" comes from sūtras ("discourses", scriptures) originating around the beginning of the common era. Jan Nattier has noted that some of the earliest Mahāyāna texts, such as the Ugraparipṛccha Sūtra use the term "Mahāyāna", yet there is no doctrinal difference between Mahāyāna in this context and the early schools. Instead, Nattier writes that in the earliest sources, "Mahāyāna" referred to the rigorous emulation of Gautama Buddha's path to Buddhahood.[17]

Some important evidence for early Mahāyāna Buddhism comes from the texts translated by the Indoscythian monk Lokakṣema in the 2nd century CE, who came to China from the kingdom of Gandhāra. These are some of the earliest known Mahāyāna texts.[43][44][note 4] Study of these texts by Paul Harrison and others show that they strongly promote monasticism (contra the lay origin theory), acknowledge the legitimacy of arhatship, and do not show any attempt to establish a new sect or order.[24] A few of these texts often emphasize ascetic practices, forest dwelling, and deep states of meditative concentration (samadhi).[45]

Indian Mahāyāna never had nor ever attempted to have a separate Vinaya or ordination lineage from the early schools of Buddhism, and therefore each bhikṣu or bhikṣuṇī adhering to the Mahāyāna formally belonged to one of the early Buddhist schools. Membership in these nikāyas, or monastic orders, continues today, with the Dharmaguptaka nikāya being used in East Asia, and the Mūlasarvāstivāda nikāya being used in Tibetan Buddhism. Therefore, Mahāyāna was never a separate monastic sect outside of the early schools.[46]

Paul Harrison clarifies that while monastic Mahāyānists belonged to a nikāya, not all members of a nikāya were Mahāyānists.[47] From Chinese monks visiting India, we now know that both Mahāyāna and non-Mahāyāna monks in India often lived in the same monasteries side by side.[48] It is also possible that, formally, Mahāyāna would have been understood as a group of monks or nuns within a larger monastery taking a vow together (known as a "kriyākarma") to memorize and study a Mahāyāna text or texts.[49]

The earliest stone inscription containing a recognizably Mahāyāna formulation and a mention of the Buddha Amitābha (an important Mahāyāna figure) was found in the Indian subcontinent in Mathura, and dated to around 180 CE. Remains of a statue of a Buddha bear the Brāhmī inscription: "Made in the year 28 of the reign of King Huviṣka, ... for the Blessed One, the Buddha Amitābha."[42] There is also some evidence that the Kushan Emperor Huviṣka himself was a follower of Mahāyāna. A Sanskrit manuscript fragment in the Schøyen Collection describes Huviṣka as having "set forth in the Mahāyāna."[50] Evidence of the name "Mahāyāna" in Indian inscriptions in the period before the 5th century is very limited in comparison to the multiplicity of Mahāyāna writings transmitted from Central Asia to China at that time.[note 5][note 6][note 7]

Based on archeological evidence, Gregory Schopen argues that Indian Mahāyāna remained "an extremely limited minority movement – if it remained at all – that attracted absolutely no documented public or popular support for at least two more centuries."[24] Likewise, Joseph Walser speaks of Mahāyāna's "virtual invisibility in the archaeological record until the fifth century".[51] Schopen also sees this movement as being in tension with other Buddhists, "struggling for recognition and acceptance".[52] Their "embattled mentality" may have led to certain elements found in Mahāyāna texts like Lotus sutra, such as a concern with preserving texts.[52]

Schopen, Harrison and Nattier also argue that these communities were probably not a single unified movement, but scattered groups based on different practices and sutras.[24] One reason for this view is that Mahāyāna sources are extremely diverse, advocating many different, often conflicting doctrines and positions, as Jan Nattier writes:[53]

Thus we find one scripture (the Aksobhya-vyuha) that advocates both srávaka and bodhisattva practices, propounds the possibility of rebirth in a pure land, and enthusiastically recommends the cult of the book, yet seems to know nothing of emptiness theory, the ten bhumis, or the trikaya, while another (the P'u-sa pen-yeh ching) propounds the ten bhumis and focuses exclusively on the path of the bodhisattva, but never discusses the paramitas. A Madhyamika treatise (Nagarjuna's Mulamadhyamika-karikas) may enthusiastically deploy the rhetoric of emptiness without ever mentioning the bodhisattva path, while a Yogacara treatise (Vasubandhu's Madhyanta-vibhaga-bhasya) may delve into the particulars of the trikaya doctrine while eschewing the doctrine of ekayana. We must be prepared, in other words, to encounter a multiplicity of Mahayanas flourishing even in India, not to mention those that developed in East Asia and Tibet.

In spite of being a minority in India, Indian Mahāyāna was an intellectually vibrant movement, which developed various schools of thought during what Jan Westerhoff has been called "The Golden Age of Indian Buddhist Philosophy" (from the beginning of the first millennium CE up to the 7th century).[54] Some major Mahāyāna traditions are Prajñāpāramitā, Mādhyamaka, Yogācāra, Buddha-nature (Tathāgatagarbha), and the school of Dignaga and Dharmakirti as the last and most recent.[55] Major early figures include Nagarjuna, Āryadeva, Aśvaghoṣa, Asanga, Vasubandhu, and Dignaga. Mahāyāna Buddhists seem to have been active in the Kushan Empire (30–375 CE), a period that saw great missionary and literary activities by Buddhists. This is supported by the works of the historian Taranatha.[56]

Growth

The Mahāyāna movement (or movements) remained quite small until it experienced much growth in the fifth century. Very few manuscripts have been found before the fifth century (the exceptions are from Bamiyan). According to Walser, "the fifth and sixth centuries appear to have been a watershed for the production of Mahāyāna manuscripts."[57] Likewise it is only in the 4th and 5th centuries CE that epigraphic evidence shows some kind of popular support for Mahāyāna, including some possible royal support at the kingdom of Shan shan as well as in Bamiyan and Mathura.[58]

Still, even after the 5th century, the epigraphic evidence which uses the term Mahāyāna is still quite small and is notably mainly monastic, not lay.[58] By this time, Chinese pilgrims, such as Faxian (337–422 CE), Xuanzang (602–664), Yijing (635–713 CE) were traveling to India, and their writings do describe monasteries which they label 'Mahāyāna' as well as monasteries where both Mahāyāna monks and non-Mahāyāna monks lived together.[59]

After the fifth century, Mahāyāna Buddhism and its institutions slowly grew in influence. Some of the most influential institutions became massive monastic university complexes such as Nalanda (established by the 5th-century CE Gupta emperor, Kumaragupta I) and Vikramashila (established under Dharmapala c. 783 to 820) which were centers of various branches of scholarship, including Mahāyāna philosophy. The Nalanda complex eventually became the largest and most influential Buddhist center in India for centuries.[60] Even so, as noted by Paul Williams, "it seems that fewer than 50 percent of the monks encountered by Xuanzang (Hsüan-tsang; c. 600–664) on his visit to India actually were Mahāyānists."[61]

Expansion outside of India

Over time Indian Mahāyāna texts and philosophy reached Central Asia and China through trade routes like the Silk Road, later spreading throughout East Asia.[39] Over time, Central Asian Buddhism became heavily influenced by Mahāyāna and it was a major source for Chinese Buddhism. Mahāyāna works have also been found in Gandhāra, indicating the importance of this region for the spread of Mahāyāna. Central Asian Mahāyāna scholars were very important in the Silk Road Transmission of Buddhism.[62] They include translators like Lokakṣema (c. 167–186), Dharmarakṣa (c. 265–313), Kumārajīva (c. 401), and Dharmakṣema (385–433). The site of Dunhuang seems to have been a particularly important place for the study of Mahāyāna Buddhism.[56]

Mahāyāna spread from China to Korea, Vietnam, and Taiwan, which (along with Korea) would later spread it to Japan.[39][40] Mahāyāna also spread from India to Myanmar, and then Sumatra and Malaysia.[39][40] Mahāyāna spread from Sumatra to other Indonesian islands, including Java and Borneo, the Philippines, Cambodia, and eventually, Indonesian Mahāyāna traditions made it to China.[39][40]

By the fourth century, Chinese monks like Faxian (c. 337–422 CE) had also begun to travel to India (now dominated by the Guptas) to bring back Buddhist teachings, especially Mahāyāna works.[63] These figures also wrote about their experiences in India and their work remains invaluable for understanding Indian Buddhism. In some cases Indian Mahāyāna traditions were directly transplanted, as with the case of the East Asian Madhymaka (by Kumārajīva) and East Asian Yogacara (especially by Xuanzang). Later, new developments in Chinese Mahāyāna led to new Chinese Buddhist traditions like Tiantai, Huayen, Pure Land and Chan Buddhism (Zen). These traditions would then spread to Korea, Vietnam and Japan.

Forms of Mahāyāna Buddhism which are mainly based on the doctrines of Indian Mahāyāna sutras are still popular in East Asian Buddhism, which is mostly dominated by various branches of Mahāyāna Buddhism. Paul Williams has noted that in this tradition in the Far East, primacy has always been given to the study of the Mahāyāna sūtras.[64]

Later developments

Beginning during the Gupta (c. 3rd century CE–575 CE) period a new movement began to develop which drew on previous Mahāyāna doctrine as well as new Pan-Indian tantric ideas. This came to be known by various names such as Vajrayāna (Tibetan: rdo rje theg pa), Mantrayāna, and Esoteric Buddhism or "Secret Mantra" (Guhyamantra). This new movement continued into the Pala era (8th century–12th century CE), during which it grew to dominate Indian Buddhism.[65] Possibly led by groups of wandering tantric yogis named mahasiddhas, this movement developed new tantric spiritual practices and also promoted new texts called the Buddhist Tantras.[66]

Philosophically, Vajrayāna Buddhist thought remained grounded in the Mahāyāna Buddhist ideas of Madhyamaka, Yogacara and Buddha-nature.[67][68] Tantric Buddhism generally deals with new forms of meditation and ritual which often makes use of the visualization of Buddhist deities (including Buddhas, bodhisattvas, dakinis, and fierce deities) and the use of mantras. Most of these practices are esoteric and require ritual initiation or introduction by a tantric master (vajracarya) or guru.[69]

The source and early origins of Vajrayāna remain a subject of debate among scholars. Some scholars like Alexis Sanderson argue that Vajrayāna derives its tantric content from Shaivism and that it developed as a result of royal courts sponsoring both Buddhism and Saivism. Sanderson argues that Vajrayāna works like the Samvara and Guhyasamaja texts show direct borrowing from Shaiva tantric literature.[70][71] However, other scholars such as Ronald M. Davidson question the idea that Indian tantrism developed in Shaivism first and that it was then adopted into Buddhism. Davidson points to the difficulties of establishing a chronology for the Shaiva tantric literature and argues that both traditions developed side by side, drawing on each other as well as on local Indian tribal religion.[72]

Whatever the case, this new tantric form of Mahāyāna Buddhism became extremely influential in India, especially in Kashmir and in the lands of the Pala Empire. It eventually also spread north into Central Asia, the Tibetan plateau and to East Asia. Vajrayāna remains the dominant form of Buddhism in Tibet, in surrounding regions like Bhutan and in Mongolia. Esoteric elements are also an important part of East Asian Buddhism where it is referred to by various terms. These include: Zhēnyán (Chinese: 真言, literally "true word", referring to mantra), Mìjiao (Chinese: 密教; Esoteric Teaching), Mìzōng (密宗; "Esoteric Tradition") or Tángmì (唐密; "Tang (Dynasty) Esoterica") in Chinese and Shingon, Tomitsu, Mikkyo, and Taimitsu in Japanese.

Worldview

Few things can be said with certainty about Mahāyāna Buddhism in general other than that the Buddhism practiced in China, Indonesia, Vietnam, Korea, Tibet, Mongolia and Japan is Mahāyāna Buddhism.[note 8] Mahāyāna can be described as a loosely bound collection of many teachings and practices (some of which are seemingly contradictory).[note 9] Mahāyāna constitutes an inclusive and broad set of traditions characterized by plurality and the adoption of a vast number of new sutras, ideas and philosophical treatises in addition to the earlier Buddhist texts.

Broadly speaking, Mahāyāna Buddhists accept the classic Buddhist doctrines found in early Buddhism (i.e. the Nikāya and Āgamas), such as the Middle Way, Dependent origination, the Four Noble Truths, the Noble Eightfold Path, the Three Jewels, the Three marks of existence and the bodhipakṣadharmas (aids to awakening).[73] Mahāyāna Buddhism further accepts some of the ideas found in Buddhist Abhidharma thought. However, Mahāyāna also adds numerous Mahāyāna texts and doctrines, which are seen as definitive and in some cases superior teachings.[74][75] D.T. Suzuki described the broad range and doctrinal liberality of Mahāyāna as "a vast ocean where all kinds of living beings are allowed to thrive in a most generous manner, almost verging on a chaos".[76]

Paul Williams refers to the main impulse behind Mahāyāna as the vision which sees the motivation to achieve Buddhahood for sake of other beings as being the supreme religious motivation. This is the way that Atisha defines Mahāyāna in his Bodhipathapradipa.[77] As such, according to Williams, "Mahāyāna is not as such an institutional identity. Rather, it is inner motivation and vision, and this inner vision can be found in anyone regardless of their institutional position."[78] Thus, instead of a specific school or sect, Mahāyāna is a "family term" or a religious tendency, which is united by "a vision of the ultimate goal of attaining full Buddhahood for the benefit of all sentient beings (the 'bodhisattva ideal') and also (or eventually) a belief that Buddhas are still around and can be contacted (hence the possibility of an ongoing revelation)."[79]

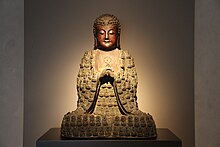

The Buddhas

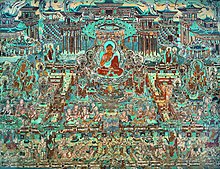

Buddhas and bodhisattvas (beings on their way to Buddhahood) are central elements of Mahāyāna. Mahāyāna has a vastly expanded cosmology and theology, with various Buddhas and powerful bodhisattvas residing in different worlds and buddha-fields (buddha kshetra).[5] Buddhas unique to Mahāyāna include the Buddhas Amitābha ("Infinite Light"), Akṣobhya ("the Imperturbable"), Bhaiṣajyaguru ("Medicine guru") and Vairocana ("the Illuminator"). In Mahāyāna, a Buddha is seen as a being that has achieved the highest kind of awakening due to his superior compassion and wish to help all beings.[80]

An important feature of Mahāyāna is the way that it understands the nature of a Buddha, which differs from non-Mahāyāna understandings. Mahāyāna texts not only often depict numerous Buddhas besides Sakyamuni, but see them as transcendental or supramundane (lokuttara) beings with great powers and huge lifetimes. The White Lotus Sutra famously describes the lifespan of the Buddha as immeasurable and states that he actually achieved Buddhahood countless of eons (kalpas) ago and has been teaching the Dharma through his numerous avatars for an unimaginable period of time.[81][82][83]

Furthermore, Buddhas are active in the world, constantly devising ways to teach and help all sentient beings. According to Paul Williams, in Mahāyāna, a Buddha is often seen as "a spiritual king, relating to and caring for the world", rather than simply a teacher who after his death "has completely 'gone beyond' the world and its cares".[84] Buddha Sakyamuni's life and death on earth are then usually understood docetically as a "mere appearance", his death is a show, while in actuality he remains out of compassion to help all sentient beings.[84] Similarly, Guang Xing describes the Buddha in Mahāyāna as an omnipotent and almighty divinity "endowed with numerous supernatural attributes and qualities".[85] Mahayana Buddhologies have often been compared to various types of theism (including pantheism) by different scholars, though there is disagreement among scholars regarding this issue as well on the general relationship between Buddhism and Theism.[86]

The idea that Buddhas remain accessible is extremely influential in Mahāyāna and also allows for the possibility of having a reciprocal relationship with a Buddha through prayer, visions, devotion and revelations.[87] Through the use of various practices, a Mahāyāna devotee can aspire to be reborn in a Buddha's pure land or buddha field (buddhakṣetra), where they can strive towards Buddhahood in the best possible conditions. Depending on the sect, liberation into a buddha-field can be obtained by faith, meditation, or sometimes even by the repetition of Buddha's name. Faith-based devotional practices focused on rebirth in pure lands are common in East Asia Pure Land Buddhism.[88]

The influential Mahāyāna concept of the three bodies (trikāya) of a Buddha developed to make sense of the transcendental nature of the Buddha. This doctrine holds that the "bodies of magical transformation" (nirmāṇakāyas) and the "enjoyment bodies" (saṃbhogakāya) are emanations from the ultimate Buddha body, the Dharmakaya, which is none other than the ultimate reality itself, i.e. emptiness or Thusness.[89]

The Bodhisattvas

The Mahāyāna bodhisattva path (mārga) or vehicle (yāna) is seen as being the superior spiritual path by Mahāyānists, over and above the paths of those who seek arhatship or "solitary buddhahood" for their own sake (Śrāvakayāna and Pratyekabuddhayāna).[90] Mahāyāna Buddhists generally hold that pursuing only the personal release from suffering i.e. nirvāṇa is a smaller or inferior aspiration (called "hinayana"), because it lacks the wish and resolve to liberate all other sentient beings from saṃsāra (the round of rebirth) by becoming a Buddha.[91][92][93]

This wish to help others by entering the Mahāyāna path is called bodhicitta and someone who engages in this path to complete buddhahood is a bodhisattva. High level bodhisattvas (with eons of practice) are seen as extremely powerful supramundane beings. They are objects of devotion and prayer throughout the Mahāyāna world.[94] Popular bodhisattvas which are revered across Mahāyāna include Avalokiteshvara, Manjushri, Tara and Maitreya. Bodhisattvas could reach the personal nirvana of the arhats, but they reject this goal and remain in saṃsāra to help others out of compassion.[95][96][94]

According to eighth-century Mahāyāna philosopher Haribhadra, the term "bodhisattva" can technically refer to those who follow any of the three vehicles, since all are working towards bodhi (awakening) and hence the technical term for a Mahāyāna bodhisattva is a mahāsattva (great being) bodhisattva.[97] According to Paul Williams, a Mahāyāna bodhisattva is best defined as:

that being who has taken the vow to be reborn, no matter how many times this may be necessary, in order to attain the highest possible goal, that of Complete and Perfect Buddhahood. This is for the benefit of all sentient beings.[97]

There are two models for the nature of the bodhisattvas, which are seen in the various Mahāyāna texts. One is the idea that a bodhisattva must postpone their awakening until full Buddhahood is attained. This could take eons and in the meantime, they will help countless beings. After reaching Buddhahood, they do pass on to nirvāṇa (after which they do not return). The second model is the idea that there are two kinds of nirvāṇa, the nirvāṇa of an arhat and a superior type of nirvāṇa called apratiṣṭhita (non-abiding, not-established) that allows a Buddha to remain forever engaged in the world. As noted by Paul Williams, the idea of apratiṣṭhita nirvāṇa may have taken some time to develop and is not obvious in some of the early Mahāyāna literature.[96]

The Bodhisattva Path

In most classic Mahāyāna sources (as well as in non-Mahāyāna sources on the topic), the bodhisattva path is said to take three or four asaṃkheyyas ("incalculable eons"), requiring a huge number of lifetimes of practice to complete.[99][100] However, certain practices are sometimes held to provide shortcuts to Buddhahood (these vary widely by tradition). According to the Bodhipathapradīpa (A Lamp for the Path to Awakening) by the Indian master Atiśa, the central defining feature of a bodhisattva's path is the universal aspiration to end suffering for themselves and all other beings, i.e. bodhicitta.[101]

The bodhisattva's spiritual path is traditionally held to begin with the revolutionary event called the "arising of the Awakening Mind" (bodhicittotpāda), which is the wish to become a Buddha in order to help all beings.[100] This is achieved in different ways, such as the meditation taught by the Indian master Shantideva in his Bodhicaryavatara called "equalising self and others and exchanging self and others". Other Indian masters like Atisha and Kamalashila also teach a meditation in which we contemplate how all beings have been our close relatives or friends in past lives. This contemplation leads to the arising of deep love (maitrī) and compassion (karuṇā) for others, and thus bodhicitta is generated.[102] According to the Indian philosopher Shantideva, when great compassion and bodhicitta arises in a person's heart, they cease to be an ordinary person and become a "son or daughter of the Buddhas".[101]

The idea of the bodhisattva is not unique to Mahāyāna Buddhism and it is found in Theravada and other early Buddhist schools. However, these schools held that becoming a bodhisattva required a prediction of one's future Buddhahood in the presence of a living Buddha.[103] In Mahāyāna, the term bodhisattva is applicable to any person from the moment they intend to become a Buddha (i.e. the moment in which bodhicitta arises in their mind) and without the requirement of a living Buddha being present.[103] Some Mahāyāna sūtras like the Lotus Sutra promote the bodhisattva path as being universal and open to everyone. Other texts disagree with this and state that only some beings have the capacity for Buddhahood.[104]

The generation of bodhicitta may then be followed by the taking of the bodhisattva vows (praṇidhāna) to "lead to Nirvana the whole immeasurable world of beings" as the Prajñaparamita sutras state. This compassionate commitment to help others is the central characteristic of the Mahāyāna bodhisattva.[105] These vows may be accompanied by certain ethical guidelines called bodhisattva precepts. Numerous sutras also state that a key part of the bodhisattva path is the practice of a set of virtues called pāramitās (transcendent or supreme virtues). Sometimes six are outlined: giving, ethical discipline, patient endurance, diligence, meditation and transcendent wisdom.[106][5]

Other sutras (like the Daśabhūmika) give a list of ten, with the addition of upāya (skillful means), praṇidhāna (vow, resolution), Bala (spiritual power) and Jñāna (knowledge).[107] Prajñā (transcendent knowledge or wisdom) is arguably the most important virtue of the bodhisattva. This refers to an understanding of the emptiness of all phenomena, arising from study, deep consideration and meditation.[105]

Bodhisattva levels

Various Mahāyāna Buddhist scriptures associate the beginning of the bodhisattva practice with what is called the "path of accumulation" or equipment (saṃbhāra-mārga), which is the first path of the classic five paths schema.[108]

The Daśabhūmika Sūtra as well as other texts also outline a series of bodhisattva levels or spiritual stages (bhūmis ) on the path to Buddhahood. The various texts disagree on the number of stages however, the Daśabhūmika giving ten for example (and mapping each one to the ten paramitas), the Bodhisattvabhūmi giving seven and thirteen and the Avatamsaka outlining 40 stages.[107]

In later Mahāyāna scholasticism, such as in the work of Kamalashila and Atiśa, the five paths and ten bhūmi systems are merged and this is the progressive path model that is used in Tibetan Buddhism. According to Paul Williams, in these systems, the first bhūmi is reached once one attains "direct, nonconceptual and nondual insight into emptiness in meditative absorption", which is associated with the path of seeing (darśana-mārga).[108] At this point, a bodhisattva is considered an ārya (a noble being).[109]

Skillful means and the One Vehicle

Skillful means or Expedient techniques (Skt. upāya) is another important virtue and doctrine in Mahāyāna Buddhism.[110] The idea is most famously expounded in the White Lotus Sutra, and refers to any effective method or technique that is conducive to spiritual growth and leads beings to awakening and nirvana. This doctrine states that, out of compassion, the Buddha adapts his teaching to whomever he is teaching. Because of this, it is possible that the Buddha may teach seemingly contradictory things to different people. This idea is also used to explain the vast textual corpus found in Mahāyāna.[111]

A closely related teaching is the doctrine of the One Vehicle (ekayāna). This teaching states that even though the Buddha is said to have taught three vehicles (the disciples' vehicle, the vehicle of solitary Buddhas and the bodhisattva vehicle, which are accepted by all early Buddhist schools), these actually are all skillful means which lead to the same place: Buddhahood. Therefore, there really are not three vehicles in an ultimate sense, but one vehicle, the supreme vehicle of the Buddhas, which is taught in different ways depending on the faculties of individuals. Even those beings who think they have finished the path (i.e. the arhats) are actually not done, and they will eventually reach Buddhahood.[111]

This doctrine was not accepted in full by all Mahāyāna traditions. The Yogācāra school famously defended an alternative theory that held that not all beings could become Buddhas. This became a subject of much debate throughout Mahāyāna Buddhist history.[112]

Prajñāpāramitā (Transcendent Knowledge)

Some of the key Mahāyāna teachings are found in the Prajñāpāramitā ("Transcendent Knowledge" or "Perfection of Wisdom") texts, which are some of the earliest Mahāyāna works.[113] Prajñāpāramitā is a deep knowledge of reality which Buddhas and bodhisattvas attain. It is a transcendent, non-conceptual and non-dual kind of knowledge into the true nature of things.[114] This wisdom is also associated with insight into the emptiness (śūnyatā) of dharmas (phenomena) and their illusory nature (māyā).[115] This amounts to the idea that all phenomena (dharmas) without exception have "no essential unchanging core" (i.e. they lack svabhāva, an essence or inherent nature), and therefore have "no fundamentally real existence".[116] These empty phenomena are also said to be conceptual constructions.[117]

Because of this, all dharmas (things, phenomena), even the Buddha's Teaching, the Buddha himself, Nirvāṇa and all living beings, are like "illusions" or "magic" (māyā) and "dreams" (svapna).[118][117] This emptiness or lack of real existence applies even to the apparent arising and ceasing of phenomena. Because of this, all phenomena are also described as unarisen (anutpāda), unborn (ajata), "beyond coming and going" in the Prajñāpāramitā literature.[119][120] Most famously, the Heart Sutra states that "all phenomena are empty, that is, without characteristic, unproduced, unceased, stainless, not stainless, undiminished, unfilled".[121] The Prajñāpāramitā texts also use various metaphors to describe the nature of things, for example, the Diamond Sutra compares phenomena to: "A shooting star, a clouding of the sight, a lamp, an illusion, a drop of dew, a bubble, a dream, a lightning's flash, a thunder cloud."[citation needed]

Prajñāpāramitā is also associated with not grasping, not taking a stand on or "not taking up" (aparigṛhīta) anything in the world. The Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra explains it as "not grasping at form, not grasping at sensation, perception, volitions and cognition".[122] This includes not grasping or taking up even correct Buddhist ideas or mental signs (such as "not-self", "emptiness", bodhicitta, vows), since these things are ultimately all empty concepts as well.[123][117]

Attaining a state of fearless receptivity (ksanti) through the insight into the true nature of reality (Dharmatā) in an intuitive, non-conceptual manner is said to be the prajñāpāramitā, the highest spiritual wisdom. According to Edward Conze, the "patient acceptance of the non-arising of dharmas" (anutpattika-dharmakshanti) is "one of the most distinctive virtues of the Mahāyānistic saint."[124] The Prajñāpāramitā texts also claim that this training is not just for Mahāyānists, but for all Buddhists following any of the three vehicles.[125]

Madhyamaka (Centrism)

| Part of a series on |

| Buddhist philosophy |

|---|

|