A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Italy |

|---|

|

| People |

| Traditions |

Italian literature is written in the Italian language, particularly within Italy. It may also refer to literature written by Italians or in other languages spoken in Italy, often languages that are closely related to modern Italian, including regional varieties and vernacular dialects.

Italian literature began in the 12th century, when in different regions of the peninsula the Italian vernacular started to be used in a literary manner. The Ritmo laurenziano is the first extant document of Italian literature. In 1230, the Sicilian School became notable for being the first style in standard Italian. Renaissance humanism developed during the 14th and the beginning of the 15th centuries. Lorenzo de' Medici is regarded as the standard bearer of the influence of Florence on the Renaissance in the Italian states. The development of the drama in the 15th century was very great. In the 16th century, the fundamental characteristic of the era following the end of the Renaissance was that it perfected the Italian character of its language. Niccolò Machiavelli and Francesco Guicciardini were the chief originators of the science of history.[2] Pietro Bembo was an influential figure in the development of the Italian language. In 1690, the Academy of Arcadia was instituted with the goal of "restoring" literature by imitating the simplicity of the ancient shepherds with sonnets, madrigals, canzonette, and blank verses.

In the 18th century, the political condition of the Italian states began to improve, and philosophers disseminated their writings and ideas throughout Europe during the Age of Enlightenment. The leading figure of the 18th-century Italian literary revival was Giuseppe Parini.[3] The philosophical, political, and socially progressive ideas behind the French Revolution of 1789 gave a special direction to Italian literature in the second half of the 18th century, inaugurated with the publication of Dei delitti e delle pene by Cesare Beccaria. Love of liberty and desire for equality created a literature aimed at national objects. Patriotism and classicism were the two principles that inspired the literature that began with the Italian dramatist and poet Vittorio Alfieri.[3] The Romantic movement had as its organ the Conciliatore, established in 1818 at Milan. The main instigator of the reform was the Italian poet and novelist Alessandro Manzoni. The great Italian poet of the age was Giacomo Leopardi. The literary movement that preceded and was contemporary with the political revolutions of 1848 may be said to be represented by four writers: Giuseppe Giusti, Francesco Domenico Guerrazzi, Vincenzo Gioberti, and Cesare Balbo.[4]

After the Risorgimento, political literature became less important. The first part of this period is characterized by two divergent trends of literature that both opposed Romanticism: the Scapigliatura and Verismo. Important early 20th-century Italian writers include Giovanni Pascoli, Italo Svevo, Gabriele D'Annunzio, Umberto Saba, Giuseppe Ungaretti, Eugenio Montale, and Luigi Pirandello. Neorealism was developed by Alberto Moravia. Pier Paolo Pasolini became notable for being one of the most controversial authors in the history of Italy. Umberto Eco became internationally successful with the Medieval detective story Il nome della rosa (1980). The Nobel Prize in Literature has been awarded to Italian language authors six times (as of 2019) with winners including Giosuè Carducci, Grazia Deledda, Luigi Pirandello, Salvatore Quasimodo, Eugenio Montale, and Dario Fo.

Early medieval Latin literature

| This article is part of the series on the |

| Italian language |

|---|

| History |

| Literature and other |

| Grammar |

| Alphabet |

| Phonology |

As the Western Roman Empire declined, the Latin tradition was kept alive by writers such as Cassiodorus, Boethius, and Symmachus. The liberal arts flourished at Ravenna under Theodoric, and the Gothic kings surrounded themselves with masters of rhetoric and of grammar. Some lay schools remained in Italy, and noted scholars included Magnus Felix Ennodius, Arator, Venantius Fortunatus, Felix the Grammarian, Peter of Pisa, Paulinus of Aquileia, and many others.

The later establishment of the medieval universities of Bologna, Padua, Vicenza, Naples, Salerno, Modena and Parma helped to spread culture and prepared the ground in which the new vernacular literature developed.[5] Classical traditions did not disappear, and affection for the memory of Rome, a preoccupation with politics, and a preference for practice over theory combined to influence the development of Italian literature.[6]

High medieval literature

Trovatori

The earliest vernacular literary tradition in Italy was in Occitan, spoken in parts of northwest Italy. A tradition of vernacular lyric poetry arose in Poitou in the early 12th century and spread south and east, eventually reaching Italy by the end of the 12th century. The first troubadours (trovatori in Italian), as these Occitan lyric poets were called, to practise in Italy were from elsewhere, but the high aristocracy of the Northern Italy was ready to patronise them.[7] It was not long before native Italians adopted Occitan as a vehicle for poetic expression.

Among the early patrons of foreign troubadours were especially the House of Este, the Da Romano, House of Savoy, and the Malaspina. Azzo VI of Este entertained the troubadours Aimeric de Belenoi, Aimeric de Peguilhan, Albertet de Sestaro, and Peire Raimon de Tolosa from Occitania and Rambertino Buvalelli from Bologna, one of the earliest Italian troubadours. Azzo VI's daughter, Beatrice, was an object of the early poets "courtly love". Azzo's son, Azzo VII, hosted Elias Cairel and Arnaut Catalan. Rambertino was named podestà of Genoa in 1218 and it was probably during his three-year tenure there that he introduced Occitan lyric poetry to the city, which later developed a flourishing Occitan literary culture.[8]

The margraves of Montferrat—Boniface I, William VI, and Boniface II—were patrons of Occitan poetry. Among the Genoese troubadours were Lanfranc Cigala, Calega Panzan, Jacme Grils, and Bonifaci Calvo. Genoa was also the place of the genesis of the podestà-troubadour phenomenon: men who served in several cities as podestàs on behalf of either the Guelph or Ghibelline party and who wrote political poetry in Occitan. Rambertino Buvalelli was the first podestà-troubadour and in Genoa there were the Guelphs Luca Grimaldi and Luchetto Gattilusio and the Ghibellines Perceval and Simon Doria.

Perhaps the most important aspect of the Italian troubadour phenomenon was the production of chansonniers and the composition of vidas and razos.[9] Uc de Saint Circ undertook to author the entire razo corpus and a great many of the vidas. The most famous and influential Italian troubadour was Sordello.[10]

The troubadours had a connection with the rise of a school of poetry in the Kingdom of Sicily. In 1220 Obs de Biguli was present as a "singer" at the coronation of the Emperor Frederick II. Guillem Augier Novella before 1230 and Guilhem Figueira thereafter were important Occitan poets at Frederick's court. The Albigensian Crusade had devastated Languedoc and forced many troubadours of the area to flee to Italy, where an Italian tradition of papal criticism was begun.[11]

Chivalric romance

The Historia de excidio Trojae, attributed to Dares Phrygius, claimed to be an eyewitness account of the Trojan War. Guido delle Colonne of Messina, one of the vernacular poets of the Sicilian school, composed the Historia destructionis Troiae. In his poetry, Guido was an imitator of the Provençals,[6] but in this book he converted Benoît de Sainte-Maure's French romance into what sounded like serious Latin history.[12]

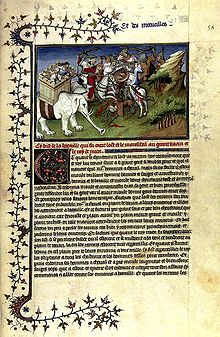

Much the same thing occurred with other great legends. Quilichino of Spoleto wrote couplets about the legend of Alexander the Great. Europe was full of the legend of King Arthur, but the Italians contented themselves with translating and abridging French romances. Jacobus de Voragine, while collecting his Golden Legend (1260), remained a historian.[13] Farfa, Marsicano, and other scholars translated Aristotle, the precepts of the school of Salerno, and the travels of Marco Polo, linking the classics and the Renaissance.[6]

At the same time, epic poetry was written in a mixed language, a dialect of Italian based on French: hybrid words exhibited a treatment of sounds according to the rules of both languages, had French roots with Italian endings, and were pronounced according to Italian or Latin rules. Examples include the chansons de geste, Macaire, the Entrée d'Espagne written by Anonymous of Padua, the Prise de Pampelune, written by Niccolò of Verona, and others. All this preceded the appearance of purely Italian literature.[14][15]

Emergence of native vernacular literature

The French and Occitan languages gradually gave way to the native Italian. Hybridism recurred, but it no longer predominated. In the Bovo d'Antona and the Rainaldo e Lesengrino, Venetian is clearly felt, although the language is influenced by French forms. These writings, which Graziadio Isaia Ascoli has called miste (mixed), immediately preceded the appearance of purely Italian works.[6]

There is evidence that a kind of literature already existed before the 13th century: The Ritmo cassinese, Ritmo di Sant'Alessio, Laudes creaturarum, Ritmo lucchese, Ritmo laurenziano, Ritmo bellunese are classified by Cesare Segre, et al. as "Archaic Works" (Componimenti Arcaici): "such are labelled the first literary works in the Italian vernacular, their dates ranging from the last decades of the 12th century to the early decades of the 13th".[5] However, as he points out, such early literature does not yet present any uniform stylistic or linguistic traits.[5]

This early development, however, was simultaneous in the whole peninsula, varying only in the subject matter of the art. In the north, the poems of Giacomino da Verona and Bonvesin da la Riva were written in a dialect of Lombard and Venetian.[16][17] This sort of composition may have been encouraged by the old custom in the north of Italy of listening to the songs of the jongleurs.[18]

Sicilian School

The year 1230 marked the beginning of the Sicilian School and of literature showing more uniform traits. Its importance lies more in the language (the creation of the first standard Italian) than its subject, a love song partly modelled on the Provençal poetry imported to the south by the Normans and the Svevs under Frederick II.[19] This poetry differs from the French equivalent in its treatment of the woman, less erotic and more platonic, a vein further developed by Dolce Stil Novo in later 13th-century Bologna and Florence. The customary repertoire of chivalry terms is adapted to Italian phonotactics, creating new Italian vocabulary. These were adopted by Dante and his contemporaries, and handed on to future generations of Italian writers.[19]

To the Sicilian school belonged Enzio, king of Sardinia, Pietro della Vigna, Inghilfredi, Guido and Odo delle Colonne, Jacopo d'Aquino, Ruggieri Apugliese, Giacomo da Lentini, Arrigo Testa, and others. Most famous is Io m'aggio posto in core, by Giacomo da Lentini, the head of the movement, but there is also poetry written by Frederick himself. Giacomo da Lentini is also credited with inventing the sonnet, a form later perfected by Dante, Petrarch and Boccaccio.[20] The censorship imposed by Frederick meant that no political matter entered literary debate. In this respect, the poetry of the north, still divided into communes or city-states with relatively democratic governments, provided new ideas. These new ideas are shown in the Sirventese genre, and later, Dante's Commedia, full of invectives against contemporary political leaders and popes.

Though the conventional love song prevailed at Frederick's (and later Manfred's) court, more spontaneous poetry existed in the Contrasto attributed to Cielo d'Alcamo. The Contrasto is probably a scholarly re-elaboration of a lost popular rhyme and is the closest to a kind of poetry that perished or was smothered by the ancient Sicilian literature.[19] The poems of the Sicilian school were written in the first known standard Italian.[21] This was elaborated by these poets under the direction of Frederick II and combines many traits typical of the Sicilian, and to a lesser extent, Apulian dialects and other southern dialects, with many words of Latin and French origin.

Dante's styles illustre, cardinale, aulico, curiale were developed from his linguistic study of the Sicilian School, whose technical features had been imported by Guittone d'Arezzo in Tuscany. The standard changed slightly in Tuscany because Tuscan scriveners perceived the five-vowel system used by southern Italians as a seven-vowel one. As a consequence, the texts that Italian students read in their anthology contain lines that appear not to rhyme, a feature known as ″Sicilian rhyme" (rima siciliana) which was widely used later by poets such as Dante or Petrarch.[22]

Religious literature

The earliest preserved sermons in the Italian language are from Jordan of Pisa, a Dominican.[23] Francis of Assisi, the founder of the Franciscans, also wrote poetry. According to legend, Francis dictated the hymn Cantico del Sole in the eighteenth year of his penance.[24][25] It was the first great poetical work of Northern Italy, written in a kind of verse marked by assonance, a poetic device more widespread in Northern Europe.

Jacopone da Todi was a poet who represented the religious feeling that had made special progress in Umbria. Jacopone was possessed by St. Francis's mysticism, but was also a satirist who mocked the corruption and hypocrisy of the Church.[26] The religious movement in Umbria was followed by another literary phenomenon, the religious drama. In 1258 a hermit, Raniero Fasani, represented himself as sent by God to disclose mysterious visions, and to announce to the world terrible visitations.[27] Fasani's pronouncements stimulated the formation of the Compagnie di Disciplinanti, who, for a penance, scourged themselves until they drew blood, and sang Laudi in dialogue in their confraternities. These laudi, closely connected with the liturgy, were the first example of drama in the vernacular tongue of Italy. They were written in the Umbrian dialect, in verses of eight syllables. As early as the end of the 13th century the Devozioni del Giovedi e Venerdi Santo appeared, mixing liturgy and drama. Later, di un Monaco che andò al servizio di Dio ("of a monk who entered the service of God") approached the definite form the religious drama would assume in the following centuries.[24]

First Tuscan literature

13th-century Tuscans spoke a dialect that closely resembled Latin and afterwards became, almost exclusively, the language of literature, and which was already regarded at the end of the 13th century as surpassing other dialects.[28] In Tuscany, too, popular love poetry existed. A school of imitators of the Sicilians was led by Dante da Majano, but its literary originality took another line — that of humorous and satirical poetry.[29] The entirely democratic form of government created a style of poetry that stood strongly against the medieval mystic and chivalrous style. The sonnets of Rustico di Filippo are half-fun and half-satire, as is the work of Cecco Angiolieri of Siena, the oldest known humorist.[30][31] Another kind of poetry also began in Tuscany. Guittone d'Arezzo made art quit chivalry and Provençal forms for national motives and Latin forms. He attempted political poetry and prepared the way for the Bolognese school. Bologna was the city of science, and philosophical poetry appeared there. Guido Guinizelli was the poet after the new fashion of the art. In his work, the ideas of chivalry are changed and enlarged.[30] Guinizelli's Canzoni make up the bible of Dolce Stil Novo, and one in particular, "Al cor gentil" ("To a Kind Heart") is considered the manifesto of the new movement that bloomed in Florence under Cavalcanti, Dante, and their followers.[32] He marks a great development in the history of Italian art, especially because of his close connection with Dante's lyric poetry.

In the 13th century, there were several major allegorical poems. One of these is by Brunetto Latini: his Tesoretto is a short poem, in seven-syllable verses, rhyming in couplets, in which the author is lost in a wilderness and meets a lady, who represents Nature and gives him much instruction. Francesco da Barberino wrote two little allegorical poems, the Documenti d'amore and Del reggimento e dei costumi delle donne.[30] The poems today are generally studied not as literature, but for historical context.[33]

In the 15th century, humanist and publisher Aldus Manutius published Tuscan poets Petrarch and Dante Alighieri (The Divine Comedy), creating the model for what became a standard for modern Italian.[34]

Development of early prose

Italian prose of the 13th century was as abundant and varied as its poetry.[35] Halfway through the century, a certain Aldobrando or Aldobrandino wrote a book for Beatrice of Savoy, called Le Régime du corps. In 1267 Martino da Canale wrote a history of Venice in the same Old French (langue d'oïl). Rustichello da Pisa composed many chivalrous romances, derived from the Arthurian cycle, and subsequently wrote the Travels of Marco Polo, which may have been dictated by Polo himself.[36] And finally Brunetto Latini wrote his Tesoro in French.[30] Latini also wrote some works in Italian prose such as La rettorica, an adaptation from Cicero's De inventione, and translated three orations from Cicero. Another important writer was the Florentine judge Bono Giamboni, who translated Orosius's Historiae adversus paganos, Vegetius's Epitoma rei militaris, made a translation/adaptation of Cicero's De inventione mixed with the Rethorica ad Erennium, and a translation/adaptation of Innocent III's De miseria humane conditionis. He also wrote an allegorical novel called Libro de' Vizi e delle Virtudi. Andrea of Grosseto, in 1268, translated three Treaties of Albertanus of Brescia, from Latin to Tuscan.[37]

After the original compositions in the langue d'oïl came translations or adaptations from the same. There are some moral narratives taken from religious legends, a romance of Julius Caesar, some short histories of ancient knights, the Tavola rotonda, translations of the Viaggi of Marco Polo, and of Latini's Tesoro. At the same time, translations from Latin of moral and ascetic works, histories, and treatises on rhetoric and oratory appeared. Also noteworthy is Composizione del mondo, a scientific book by Ristoro d'Arezzo, who lived about the middle of the 13th century.[38]

Another short treatise exists: De regimine rectoris, by Fra Paolino, a Minorite friar of Venice, who was bishop of Pozzuoli, and who also wrote a Latin chronicle. His treatise stands in close relation to that of Egidio Colonna, De regimine principum. It is written in Venetian.[30]

The 13th century was very rich in tales.[39] A collection called the Cento Novelle antiche contains stories drawn from many sources, including Asian, Greek and Trojan traditions, ancient and medieval history, the legends of Brittany, Provence and Italy, the Bible, local Italian traditions, and histories of animals and old mythology.[30]

On the whole the Italian novels of the 13th century have little originality, and are a faint reflection of the very rich legendary literature of France. Some attention should be paid to the Lettere of Fra Guittone d'Arezzo, who wrote many poems and also some letters in prose, the subjects of which are moral and religious. Guittone's love of antiquity and the traditions of Rome and its language was so strong that he tried to write Italian in a Latin style. The letters are obscure, involved and altogether barbarous. Guittone took as his special model Seneca the Younger, Aristotle, Cicero, Boethius and Augustine of Hippo.[40] Guittone viewed his style as very artistic, but later scholars view it as extravagant and grotesque.[30]

Dolce Stil Novo

With the school of Lapo Gianni, Guido Cavalcanti, Cino da Pistoia and Dante Alighieri, lyric poetry became exclusively Tuscan.[41][42] The whole novelty and poetic power of this school, consisted in, according to Dante, Quando Amore spira, noto, ed a quel niodo Ch'ei detta dentro, vo significando: that is, in a power of expressing the feelings of the soul in the way in which love inspires them, in an appropriate and graceful manner, fitting form to matter, and by art fusing one with the other.[43] This a neo-platonic approach widely endorsed by Dolce Stil Novo, and although in Cavalcanti's case, it can be upsetting and even destructive, it is nonetheless a metaphysical experience able to lift man onto a higher, spiritual dimension. Gianni's new style was still influenced by the Siculo-Provençal school.[44]

Cavalcanti's poems fall into two classes: those that portray the philosopher, (il sottilissimo dialettico, as Lorenzo the Magnificent called him) and those more directly the product of his poetic nature imbued with mysticism and metaphysics. To the first set belongs the famous poem Sulla natura d'amore, which in fact is a treatise on amorous metaphysics, and was annotated later in a learned way by renowned Platonic philosophers of the 15th century, such as Marsilius Ficinus and others. On the other hand, in his Ballate, he pours himself out ingenuously, but with a consciousness of his art. The greatest of these is considered to be the ballata composed by Cavalcanti when he was banished from Florence with the party of the Bianchi in 1300, and took refuge at Sarzana.[43][45]

14th century: the roots of Renaissance

Dante

Dante Alighieri, one of the greatest of Italian poets, also shows these lyrical tendencies.[46] In 1293 he wrote La Vita Nuova, in which he idealizes love. It is a collection of poems to which Dante added narration and explication. Everything is sensual, aerial, and heavenly, and the real Beatrice is supplanted by an idealized vision of her, losing her human nature and becoming a representation of the divine.[47] La Divina Commedia tells of the poet's travels through the three realms of the dead—Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise—accompanied by the Latin poet Virgil. An allegorical meaning hides under the literal one of this great epic. Dante, travelling through Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise, symbolizes mankind aiming at the double object of temporal and eternal happiness. The forest where the poet loses himself lost symbolizes sin.[48] The mountain illuminated by the sun is the universal monarchy.[43] Envy is Florence, Pride is the house of France, and Avarice is the papal court. Virgil represents reason and the empire.[49] Beatrice is the symbol of the supernatural aid mankind must have to attain the supreme end, which is God.[43]

The merit of the poem lies is the individual art of the poet, the classic art transfused for the first time into a Romance form. Whether he describes nature, analyses passions, curses the vices or sings hymns to the virtues, Dante is notable for the grandeur and delicacy of his art. He took the materials for his poem from theology, philosophy, history, and mythology, but especially from his own passions, from hatred and love.[50] The Divina Commedia ranks among the finest works of world literature.[51]

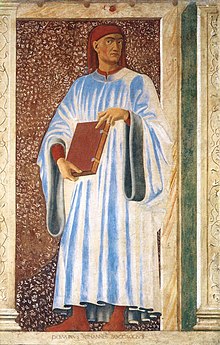

Petrarch

Petrarch was the first humanist, and he was at the same time the first modern lyric poet.[52][53] His career was long and tempestuous. He lived for many years at Avignon, cursing the corruption of the papal court; he travelled through nearly the whole of Europe; he corresponded with emperors and popes, and he was considered the most important writer of his time.[43] Petrarch's lyric verse is quite different, not only from that of the Provençal troubadours and the Italian poets before him, but also from the lyrics of Dante.[54] Petrarch is a psychological poet, who examines all his feelings and renders them with an art of exquisite sweetness. The lyrics of Petrarch are no longer transcendental like Dante's, but keep entirely within human limits.

The Canzoniere includes a few political poems, one supposed to be addressed to Cola di Rienzi and several sonnets against the court of Avignon. These are remarkable for their vigour of feeling, and also for showing that, compared to Dante, Petrarch had a sense of a broader Italian consciousness.[55]

Boccaccio

Giovanni Boccaccio had the same enthusiastic love of antiquity and the same worship for the new Italian literature as Petrarch.[56] He was the first to put together a Latin translation of the Iliad and, in 1375, the Odyssey. His classical learning was shown in the work De genealogia deorum; as A. H. Heeren said, it is an encyclopaedia of mythological knowledge; and it was the precursor of the humanist movement of the 15th century.[57] Boccaccio was also the first historian of women in his De mulieribus claris, and the first to tell the story of the great unfortunates in his De casibus virorum illustrium. He continued and perfected former geographical investigations in his De montibus, silvis, fontibus, lacubus, fluminibus, stagnis, et paludibus, et de nominibus maris, for which he made use of Vibius Sequester.

He did not invent the octave stanza, but was the first to use it in a work of length and artistic merit, his Teseide, the oldest Italian romantic poem. The Filostrato relates the loves of Troiolo and Griseida (Troilus and Cressida). The Ninfale fiesolano tells the love story of the nymph Mesola and the shepherd Africo. The Amorosa Visione, a poem in triplets, doubtless owed its origin to the Divina Commedia. The Ameto is a mixture of prose and poetry, and is the first Italian pastoral romance.[58] Boccaccio became famous principally for the Italian work, Decamerone, a collection of a hundred novels, related by a party of men and women who retired to a villa near Florence to escape the plague in 1348. Novel writing, so abundant in the preceding centuries, especially in France, now for the first time assumed an artistic shape.[59] The style of Boccaccio tends to the imitation of Latin, but in him, prose first took the form of elaborated art. Over and above this, in the Decamerone, Boccaccio is a delineator of character and an observer of passions. Much has been written about the sources of the novels of the Decamerone. Probably Boccaccio made use both of written and of oral sources.[58]

Others

Imitators

Fazio degli Uberti and Federico Frezzi were imitators of the Divina Commedia, but only in its external form.[60] Giovanni Fiorentino wrote, under the title of Pecorone, a collection of tales, which are supposed to have been related by a monk and a nun in the parlour of the monastery Novelists of Forli.[61] He closely imitated Boccaccio, and drew on Villani's chronicle for his historical stories. Franco Sacchetti wrote tales too, for the most part on subjects taken from Florentine history. The subjects are almost always improper, but it is evident that Sacchetti collected these anecdotes so he could draw his own conclusions and moral reflections, which he puts at the end of each story. From this point of view, Sacchetti's work comes near to the Monalisaliones of the Middle Ages. A third novelist was Giovanni Sercambi of Lucca, who after 1374 wrote a book, in imitation of Boccaccio, about a party of people who were supposed to fly from a plague and to go travelling about in different Italian cities, stopping here and there telling stories.[62] Later, but important, names are those of Masuccio Salernitano (Tommaso Guardato), who wrote the Novellino, and Antonio Cornazzano whose Proverbii became extremely popular.[63]

Chronicles

Chronicles formerly believed to have been of the 13th century are now mainly regarded as forgeries.[64] At the end of the 13th century there is a chronicle by Dino Compagni, probably authentic.[65]

Giovanni Villani, born in 1300, was more of a chronicler than a historian.[66] He relates the events up to 1347. The journeys that he made in Italy and France, and the information thus acquired, mean that his chronicle, the Historie Fiorentine, covers events all over Europe.[65] Matteo was the brother of Giovanni Villani, and continued the chronicle up to 1363. It was again continued by Filippo Villani.[67]

Ascetics

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Italian_literatureText je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk