A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Friulian | |

|---|---|

| furlan | |

| Native to | Italy |

| Region | Friuli |

| Ethnicity | Friulians |

Native speakers | Regular speakers: 420,000 (2014)[1] Total: 600,000 (2014)[1] |

Indo-European

| |

| Latin (Friulian alphabet) | |

| Official status | |

| Regulated by | Agjenzie regjonâl pe lenghe furlane |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | fur |

| ISO 639-3 | fur |

| Glottolog | friu1240 |

| ELP | Friulian |

| Linguasphere | 51-AAA-m |

| |

Friulian (/friˈuːliən/ free-OO-lee-ən) or Friulan (natively ⓘ or marilenghe; Italian: friulano; Austrian German: Furlanisch; Slovene: furlanščina) is a Romance language belonging to the Rhaeto-Romance family, spoken in the Friuli region of northeastern Italy. Friulian has around 600,000 speakers, the vast majority of whom also speak Italian. It is sometimes called Eastern Ladin since it shares the same roots as Ladin, but over the centuries, it has diverged under the influence of surrounding languages, including German, Italian, Venetian, and Slovene. Documents in Friulian are attested from the 11th century and poetry and literature date as far back as 1300. By the 20th century, there was a revival of interest in the language.

History

A question that causes many debates is the influence of the Latin spoken in Aquileia and surrounding areas. Some claim that it had peculiar features that later passed into Friulian. Epigraphs and inscriptions from that period show some variants if compared to the standard Latin language, but most of them are common to other areas of the Roman Empire. Often, it is cited that Fortunatianus, the bishop of Aquileia c. 342–357 AD, wrote a commentary to the Gospel in sermo rusticus (the common/rustic language), which, therefore, would have been quite divergent from the standard Latin of administration.[3] The text itself did not survive so its language cannot be examined, but its attested existence testifies to a shift of languages while, for example, other important communities of Northern Italy were still speaking Latin. The language spoken before the arrival of the Romans in 181 BC was of Celtic origin since the inhabitants belonged to the Carni, a Celtic population.[4] In modern Friulian, the words of Celtic origins are many (terms referring to mountains, woods, plants, animals, inter alia) and much influence of the original population is shown in toponyms (names of villages with -acco, -icco).[5] Even influences from the Lombardic language — Friuli was one of their strongholds — are very frequent. In a similar manner, there are unique connections to the modern, nearby Lombard language.

In Friulian, there is also a plethora of words of German, Slovenian and Venetian origin. From that evidence, scholars today agree that the formation of Friulian dates back to circa 1000 AD, at the same time as other dialects derived from Latin (see Vulgar Latin). The first written records of Friulian have been found in administrative acts of the 13th century, but the documents became more frequent in the following century, when literary works also emerged (Frammenti letterari for example). The main centre at that time was Cividale. The Friulian language has never acquired primary official status: legal statutes were first written in Latin, then in Venetian and finally in Italian.

The "Ladin Question"

The idea of unity among Ladin, Romansh and Friulian comes from the Italian historical linguist Graziadio Isaia Ascoli, who was born in Gorizia. In 1871, he presented his theory that these three languages are part of one family, which in the past stretched from Switzerland to Muggia and perhaps also Istria. The three languages are the only survivors of this family and all developed differently. Friulian was much less influenced by German. The scholar Francescato claimed subsequently that until the 14th century, the Venetian language shared many phonetic features with Friulian and Ladin and so he thought that Friulian was a much more conservative language. Many features that Ascoli thought were peculiar to the Rhaeto-Romance languages can, in fact, be found in other languages of Northern Italy.

Areas

Italy

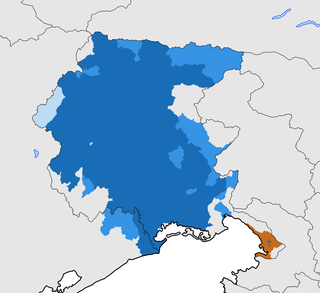

Today, Friulian is spoken in the province of Udine, including the area of the Carnia Alps, but as well throughout the province of Pordenone, in half of the province of Gorizia, and in the eastern part of the province of Venice. In the past, the language borders were wider since in Trieste and Muggia, local variants of Friulian were spoken. The main document about the dialect of Trieste, or tergestino, is "Dialoghi piacevoli in dialetto vernacolo triestino", published by G. Mainati in 1828.

World

Friuli was, until the 1960s, an area of deep poverty, causing a large number of Friulian speakers to emigrate. Most went to France, Belgium, and Switzerland or outside Europe, to Canada, Mexico, Australia, Uruguay, Argentina, Brazil, Venezuela, the United States, and South Africa. In those countries, there are associations of Friulian immigrants (called Fogolâr furlan) that try to protect their traditions and language.

Literature

This section is missing information about Examples and english translation of 13th and 14th century texts. (May 2018) |

The first texts in Friulian date back to the 13th century and are mainly commercial or juridical acts. The examples show that Friulian was used together with Latin, which was still the administrative language. The main examples of literature that have survived (much from this period has been lost) are poems from the 14th century and are usually dedicated to the theme of love and are probably inspired by the Italian poetic movement Dolce Stil Novo. The most notable work is Piruç myò doç inculurit (which means "My pear, all colored"); it was composed by an anonymous author from Cividale del Friuli, probably in 1380.

| Original text | Version in modern Friulian |

|---|---|

| Piruç myò doç inculurit

quant yò chi viot, dut stoi ardit |

Piruç gno dolç incolorît

cuant che jo ti viôt, dut o stoi ardît |

There are few differences in the first two rows, which demonstrates that there has not been a great evolution in the language except for several words which are no longer used (for example, dum(n) lo, a word which means "child"). A modern Friulian speaker can understand these texts with only little difficulty.

The second important period for Friulian literature is the 16th century. The main author of this period was Ermes di Colorêt, who composed over 200 poems.

| Notable poets and writers: | Years active: |

|---|---|

| Ermes di Colorêt | 1622–1692 |

| Pietro Zorutti | 1792–1867 |

| Caterina Percoto | 1812–1887 |

| Novella Cantarutti | 1920–2009 |

| Pier Paolo Pasolini | 1922–1975 |

| Rina Del Nin Cralli (Canada) | 1929–2021 |

| Carlo Sgorlon | 1930–2009 |

Phonology

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (July 2012) |

Consonants

| Labial | Dental/ Alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | (ŋ) | |

| Plosive | voiceless | p | t | c | k |

| voiced | b | d | ɟ | ɡ | |

| Affricate | voiceless | ts | tʃ | ||

| voiced | dz | dʒ | |||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s | (ʃ) | |

| voiced | v | z | (ʒ) | ||

| Trill | r | ||||

| Approximant | w | l | j | ||

Notes:

- /m, p, b/ are bilabial, whereas /f, v/ are labiodental and ?pojem= is labiovelar.

- Note that, in the standard language, a phonemic distinction exists between true palatal stops and palatoalveolar affricates . The former (written ⟨cj gj⟩) originate from Latin ⟨c g⟩ before ⟨a⟩, whereas the latter (written ⟨c/ç z⟩, where ⟨c⟩ is found before ⟨e⟩ and ⟨i⟩, and ⟨ç⟩ is found elsewhere) originate primarily from Latin ⟨c g⟩ before ⟨e⟩ and ⟨i⟩. The palatalization of Latin ⟨c⟩ and ⟨g⟩ before ⟨a⟩ is characteristic of the Rhaeto-Romance languages and is also found in French and some Occitan varieties. In some Friulian dialects (e.g. Western dialects), corresponding to Central are found . Note in addition that, due to various sound changes, these sounds are all now phonemic; note, for example, the minimal pair cjoc "drunk" vs. çoc "log".

Vowels

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i iː | u uː | |

| Close mid | e eː | o oː | |

| Open mid | ɛ | ɔ | |

| Open | a aː |

Orthography

Some notes on orthography (from the perspective of the standard, i.e. Central, dialect):[9]

- Long vowels are indicated with a circumflex: ⟨â ê î ô û⟩.

- ⟨e⟩ is used for both /ɛ/ (which only occurs in stressed syllables) and /e/; similarly, ⟨o⟩ is used for both /ɔ/ and /o/.

- /j/ is spelled ⟨j⟩ word-initially, and ⟨i⟩ elsewhere.

- ?pojem= occurs primarily in diphthongs, and is spelled ⟨u⟩.

- /s/ is normally spelled ⟨s⟩, but is spelled ⟨ss⟩ between vowels (in this context, a single ⟨s⟩ is pronounced /z/).

- /ɲ/ is spelled ⟨gn⟩, which can also occur word-finally.

- is an allophone of /n/, found word-finally, before word-final -s, and often in the prefix in-. Both sounds are spelled ⟨n⟩.

- /k/ is normally spelled ⟨c⟩, but ⟨ch⟩ before ⟨e⟩ and ⟨i⟩, as in Italian.

- /ɡ/ is normally spelled ⟨g⟩, but ⟨gh⟩ before ⟨e⟩ and ⟨i⟩, again as in Italian.

- The palatal stops /c ɟ/ are spelled ⟨cj gj⟩. Note that in some dialects, these sounds are pronounced , as described above.

- /tʃ/ is spelled ⟨c⟩ before ⟨e⟩ and ⟨i⟩, ⟨ç⟩ elsewhere. Note that in some dialects, this sound is pronounced .

- /dʒ/ is spelled ⟨z⟩. Note that in some dialects, this sound is pronounced .

- ⟨z⟩ can also represent /ts/ or /dz/ in certain words (e.g. nazion "nation", lezion "lesson").

- ⟨h⟩ is silent.

- ⟨q⟩ is no longer used except in the traditional spelling of certain proper names; similarly for ⟨g⟩ before ⟨e⟩ and ⟨i⟩.

Long vowels and their origin

Long vowels are typical of the Friulian language and greatly influence the Friulian pronunciation of Italian.

Friulian distinguishes between short and long vowels: in the following minimal pairs (long vowels are marked in the official orthography with a circumflex accent):

- lat (milk)

- lât (gone)

- fis (fixed, dense)

- fîs (sons)

- lus (luxury)

- lûs (light n.)

Friulian dialects differ in their treatment of long vowels. In certain dialects, some of the long vowels are actually diphthongs. The following chart shows how six words (sêt thirst, pît foot, fîl "wire", pôc (a) little, fûc fire, mûr "wall") are pronounced in four dialects. Each dialect uses a unique pattern of diphthongs (yellow) and monophthongs (blue) for the long vowels:

| Latin origin | West | Codroipo | Carnia | Central | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sêt "thirst" | SITIM | seːt | seit | seːt | |

| pît "foot" | PEDEM | peit | peit | piːt | piːt |

| fîl "wire" | FĪLUM | fiːl | fiːl | fiːl | fiːl |

| pôc "a little" | PAUCUM | pouk | poːk | pouk | poːk |

| fûc "fire" | FOCUM | fouk | fouk | fuːk | fuːk |

| mûr "wall" | MŪRUM | muːr | muːr | muːr | muːr |

Note that the vowels î and û in the standard language (based on the Central dialects) correspond to two different sounds in the Western dialects (including Codroipo). These sounds are not distributed randomly but correspond to different origins: Latin short E in an open syllable produces Western ei but Central iː, whereas Latin long Ī produces iː in both dialects. Similarly, Latin short O in an open syllable produces Western ou but Central uː, whereas Latin long Ū produces uː in both dialects. The word mûr, for example, means both "wall" (Latin MŪRUM) and "(he, she, it) dies" (Vulgar Latin *MORIT from Latin MORITUR); both words are pronounced muːr in Central dialects, but respectively muːr and mour in Western dialects.

Long consonants (ll, rr, and so on), frequently used in Italian, are usually absent in Friulian.

Friulian long vowels originate primarily from vowel lengthening in stressed open syllables when the following vowel was lost.[8] Friulian vowel length has no relation to vowel length in Classical Latin. For example, Latin valet yields vâl "it is worth" with a long vowel, but Latin vallem yields val "valley" with a short vowel. Long vowels aren't found when the following vowel is preserved, e.g.:

- before final -e < Latin -a, cf. short nuve "new (fem. sg.)" < Latin nova vs. long nûf "new (masc. sg.)" < Latin novum;

- before a non-final preserved vowel, cf. tivit /ˈtivit/ "tepid, lukewarm" < Latin tepidum, zinar /ˈzinar/ "son-in-law" < Latin generum, ridi /ˈridi/ "to laugh" < Vulgar Latin *rīdere (Classical rīdēre).

It is quite possible that vowel lengthening occurred originally in all stressed open syllables, and was later lost in non-final syllables.[10] Evidence of this is found, for example, in the divergent outcome of Vulgar Latin */ɛ/, which becomes /jɛ/ in originally closed syllables but /i(ː)/ in Central Friulian in originally open syllables, including when non-finally. Examples: siet "seven" < Vulgar Latin */sɛtte/ < Latin SEPTEM, word-final pît "foot" < Vulgar Latin */pɛde/ < Latin PEDEM, non-word-final tivit /ˈtivit/ "tepid, lukewarm" < Vulgar Latin */tɛpedu/ < Latin TEPIDUM.

An additional source of vowel length is compensatory lengthening before lost consonants in certain circumstances, cf. pâri "father" < Latin patrem, vôli "eye" < Latin oc(u)lum, lîre "pound" < Latin libra. This produces long vowels in non-final syllables, and was apparently a separate, later development than the primary lengthening in open syllables. Note, for example, the development of Vulgar Latin */ɛ/ in this context: */ɛ/ > */jɛ/ > iê /jeː/, as in piêre "stone" < Latin PETRAM, differing from the outcome /i(ː)/ in originally open syllables (see above).

Additional complications:

- Central Friulian has lengthening before /r/ even in originally closed syllables, cf. cjâr /caːr/ "cart" < Latin carrum (homophonous with cjâr "dear masc. sg." < Latin cārum). This represents a late, secondary development, and some conservative dialects have the expected length distinction here.

- Lengthening doesn't occur before nasal consonants even in originally open syllables, cf. pan /paŋ/ "bread" < Latin panem, prin /priŋ/ "first" < Latin prīmum.

- Special developments produced absolutely word-final long vowels and length distinctions, cf. fi "fig" < Latin FĪCUM vs. fî "son" < Latin FĪLIUM, no "no" < Latin NŌN vs. nô "we" < Latin NŌS.

Synchronic analyses of vowel length in Friulian often claim that it occurs predictably in final syllables before an underlying voiced obstruent, which is then devoiced.[11] Analyses of this sort have difficulty with long-vowel contrasts that occur non-finally (e.g. pâri "father" mentioned above) or not in front of obstruents (e.g. fi "fig" vs. fî "son", val "valley" vs. vâl "it is worth").

Morphologyedit

Friulian is quite different from Italian in its morphology; it is, in many respects, closer to French.

Nounsedit

In Friulian as in other Romance languages, nouns are either masculine or feminine (for example, "il mûr" ("the wall", masculine), "la cjadree" ("the chair", feminine).

Feminineedit

Most feminine nouns end in -e, which is pronounced, unlike in Standard French:

- cjase = house (from Latin "casa, -ae" hut)

- lune = moon (from Latin "luna, -ae")

- scuele = school (from Latin "schola, -ae")

Some feminine nouns, however, end in a consonant, including those ending in -zion, which are from Latin.

- man = hand (from Latin "manŭs, -ūs" f)

- lezion = lesson (from Latin "lectio, -nis" f

Note that in some Friulian dialects the -e feminine ending is actually an -a or an -o, which characterize the dialect area of the language and are referred to as a/o-ending dialects (e.g. cjase is spelled as cjaso or cjasa - the latter being the oldest form of the feminine ending).

Masculineedit

Most masculine nouns end either in a consonant or in -i.

- cjan = dog

- gjat = cat

- fradi = brother

- libri = book

A few masculine nouns end in -e, including sisteme (system) and probleme (problem). They are usually words coming from Ancient Greek. However, because most masculine nouns end in a consonant, it is common to find the forms sistem and problem instead, more often in print than in speech.

There are also a number of masculine nouns borrowed intact from Italian, with a final -o, like treno (train). Many of the words have been fully absorbed into the language and even form their plurals with the regular Friulian -s rather than the Italian desinence changing. Still, there are some purists, including those influential in Friulian publishing, who frown on such words and insist that the "proper" Friulian terms should be without the final -o. Despite the fact that one almost always hears treno, it is almost always written tren.

Articlesedit

The Friulian definite article (which corresponds to "the" in English) is derived from the Latin ille and takes the following forms:

| Number | Masculine | Feminine |

|---|---|---|

| Singular | il | la |

| Plural | i | lis |

Before a vowel, both il and la can be abbreviated to l' in the standard forms - for example il + arbul (the tree) becomes l'arbul. Yet, as far as the article la is concerned, modern grammar recommends that its non elided form should be preferred over the elided one: la acuile (the eagle) although in speech the two a sounds are pronounced as a single one. In the spoken language, various other articles are used.[12]

The indefinite article in Friulian (which corresponds to a and an in English) derives from the Latin unus and varies according to gender: