A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Wolf Temporal range:

Middle Pleistocene – present (810,000–0 YBP)[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

Eurasian wolf (Canis lupus lupus) at Polar Park in Bardu, Norway

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Canidae |

| Genus: | Canis |

| Species: | C. lupus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Canis lupus | |

| Subspecies | |

| |

| Global wolf range based on IUCN's 2018 assessment.[2] | |

The wolf (Canis lupus;[b] pl.: wolves), also known as the gray wolf or grey wolf, is a large canine native to Eurasia and North America. More than thirty subspecies of Canis lupus have been recognized, including the dog and dingo, though gray wolves, as popularly understood, only comprise naturally-occurring wild subspecies. The wolf is the largest extant member of the family Canidae, and is further distinguished from other Canis species by its less pointed ears and muzzle, as well as a shorter torso and a longer tail. The wolf is nonetheless related closely enough to smaller Canis species, such as the coyote and the golden jackal, to produce fertile hybrids with them. The wolf's fur is usually mottled white, brown, gray, and black, although subspecies in the arctic region may be nearly all white.

Of all members of the genus Canis, the wolf is most specialized for cooperative game hunting as demonstrated by its physical adaptations to tackling large prey, its more social nature, and its highly advanced expressive behaviour, including individual or group howling. It travels in nuclear families consisting of a mated pair accompanied by their offspring. Offspring may leave to form their own packs on the onset of sexual maturity and in response to competition for food within the pack. Wolves are also territorial, and fights over territory are among the principal causes of mortality. The wolf is mainly a carnivore and feeds on large wild hooved mammals as well as smaller animals, livestock, carrion, and garbage. Single wolves or mated pairs typically have higher success rates in hunting than do large packs. Pathogens and parasites, notably the rabies virus, may infect wolves.

The global wild wolf population was estimated to be 300,000 in 2003 and is considered to be of Least Concern by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Wolves have a long history of interactions with humans, having been despised and hunted in most pastoral communities because of their attacks on livestock, while conversely being respected in some agrarian and hunter-gatherer societies. Although the fear of wolves exists in many human societies, the majority of recorded attacks on people have been attributed to animals suffering from rabies. Wolf attacks on humans are rare because wolves are relatively few, live away from people, and have developed a fear of humans because of their experiences with hunters, farmers, ranchers, and shepherds.

Etymology

The English "wolf" stems from the Old English wulf, which is itself thought to be derived from the Proto-Germanic *wulfaz. The Proto-Indo-European root *wĺ̥kʷos may also be the source of the Latin word for the animal lupus (*lúkʷos).[5][6] The name "gray wolf" refers to the grayish colour of the species.[7]

Since pre-Christian times, Germanic peoples such as the Anglo-Saxons took on wulf as a prefix or suffix in their names. Examples include Wulfhere ("Wolf Army"), Cynewulf ("Royal Wolf"), Cēnwulf ("Bold Wolf"), Wulfheard ("Wolf-hard"), Earnwulf ("Eagle Wolf"), Wulfstān ("Wolf Stone") Æðelwulf ("Noble Wolf"), Wolfhroc ("Wolf-Frock"), Wolfhetan ("Wolf Hide"), Scrutolf ("Garb Wolf"), Wolfgang ("Wolf Gait") and Wolfdregil ("Wolf Runner").[8]

Taxonomy

| Canine phylogeny with ages of divergence | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cladogram and divergence of the gray wolf (including the domestic dog) among its closest extant relatives[9] |

In 1758, the Swedish botanist and zoologist Carl Linnaeus published in his Systema Naturae the binomial nomenclature.[4] Canis is the Latin word meaning "dog",[10] and under this genus he listed the doglike carnivores including domestic dogs, wolves, and jackals. He classified the domestic dog as Canis familiaris, and the wolf as Canis lupus.[4] Linnaeus considered the dog to be a separate species from the wolf because of its "cauda recurvata" (upturning tail) which is not found in any other canid.[11]

Subspecies

In the third edition of Mammal Species of the World published in 2005, the mammalogist W. Christopher Wozencraft listed under C. lupus 36 wild subspecies, and proposed two additional subspecies: familiaris (Linnaeus, 1758) and dingo (Meyer, 1793). Wozencraft included hallstromi—the New Guinea singing dog—as a taxonomic synonym for the dingo. Wozencraft referred to a 1999 mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) study as one of the guides in forming his decision, and listed the 38 subspecies of C. lupus under the biological common name of "wolf", the nominate subspecies being the Eurasian wolf (C. l. lupus) based on the type specimen that Linnaeus studied in Sweden.[12] Studies using paleogenomic techniques reveal that the modern wolf and the dog are sister taxa, as modern wolves are not closely related to the population of wolves that was first domesticated.[13] In 2019, a workshop hosted by the IUCN/Species Survival Commission's Canid Specialist Group considered the New Guinea singing dog and the dingo to be feral Canis familiaris, and therefore should not be assessed for the IUCN Red List.[14]

Evolution

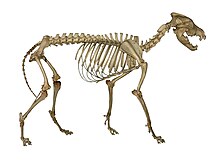

The phylogenetic descent of the extant wolf C. lupus from C. etruscus through C. mosbachensis is widely accepted.[15] The earliest fossils of C. lupus were found in what was once eastern Beringia at Old Crow, Yukon, Canada, and at Cripple Creek Sump, Fairbanks, Alaska. The age is not agreed upon but could date to one million years ago. Considerable morphological diversity existed among wolves by the Late Pleistocene. They had more robust skulls and teeth than modern wolves, often with a shortened snout, a pronounced development of the temporalis muscle, and robust premolars. It is proposed that these features were specialized adaptations for the processing of carcass and bone associated with the hunting and scavenging of Pleistocene megafauna. Compared with modern wolves, some Pleistocene wolves showed an increase in tooth breakage similar to that seen in the extinct dire wolf. This suggests they either often processed carcasses, or that they competed with other carnivores and needed to consume their prey quickly. Compared with those found in the modern spotted hyena, the frequency and location of tooth fractures in these wolves indicates they were habitual bone crackers.[16]

Genomic studies suggest modern wolves and dogs descend from a common ancestral wolf population[17][18][19] that existed 20,000 years ago.[17] A 2021 study found that the Himalayan wolf and the Indian plains wolf are part of a lineage that is basal to other wolves and split from them 200,000 years ago.[20] Other wolves appear to have originated in Beringia in an expansion that was driven by the huge ecological changes during the close of the Late Pleistocene.[21] A study in 2016 indicates that a population bottleneck was followed by a rapid radiation from an ancestral population at a time during, or just after, the Last Glacial Maximum. This implies the original morphologically diverse wolf populations were out-competed and replaced by more modern wolves.[22]

A 2016 genomic study suggests that Old World and New World wolves split around 12,500 years ago followed by the divergence of the lineage that led to dogs from other Old World wolves around 11,100–12,300 years ago.[19] An extinct Late Pleistocene wolf may have been the ancestor of the dog,[23][16] with the dog's similarity to the extant wolf being the result of genetic admixture between the two.[16] The dingo, Basenji, Tibetan Mastiff and Chinese indigenous breeds are basal members of the domestic dog clade. The divergence time for wolves in Europe, the Middle East, and Asia is estimated to be fairly recent at around 1,600 years ago. Among New World wolves, the Mexican wolf diverged around 5,400 years ago.[19]

Admixture with other canids

In the distant past, there was gene flow between African wolves, golden jackals, and gray wolves. The African wolf is a descendant of a genetically admixed canid of 72% wolf and 28% Ethiopian wolf ancestry. One African wolf from the Egyptian Sinai Peninsula showed admixture with Middle Eastern gray wolves and dogs.[24] There is evidence of gene flow between golden jackals and Middle Eastern wolves, less so with European and Asian wolves, and least with North American wolves. This indicates the golden jackal ancestry found in North American wolves may have occurred before the divergence of the Eurasian and North American wolves.[25]

The common ancestor of the coyote and the wolf admixed with a ghost population of an extinct unidentified canid. This canid was genetically close to the dhole and evolved after the divergence of the African hunting dog from the other canid species. The basal position of the coyote compared to the wolf is proposed to be due to the coyote retaining more of the mitochondrial genome of this unidentified canid.[24] Similarly, a museum specimen of a wolf from southern China collected in 1963 showed a genome that was 12–14% admixed from this unknown canid.[26] In North America, some coyotes and wolves show varying degrees of past genetic admixture.[25]

In more recent times, some male Italian wolves originated from dog ancestry, which indicates female wolves will breed with male dogs in the wild.[27] In the Caucasus Mountains, ten percent of dogs including livestock guardian dogs, are first generation hybrids.[28] Although mating between golden jackals and wolves has never been observed, evidence of jackal-wolf hybridization was discovered through mitochondrial DNA analysis of jackals living in the Caucasus Mountains[28] and in Bulgaria.[29] In 2021, a genetic study found that the dog's similarity to the extant gray wolf was the result of substantial dog-into-wolf gene flow, with little evidence of the reverse.[30]

Description

The wolf is the largest extant member of the Canidae family,[31] and is further distinguished from coyotes and jackals by a broader snout, shorter ears, a shorter torso and a longer tail.[32][31] It is slender and powerfully built, with a large, deeply descending rib cage, a sloping back, and a heavily muscled neck.[33] The wolf's legs are moderately longer than those of other canids, which enables the animal to move swiftly, and to overcome the deep snow that covers most of its geographical range in winter.[34] The ears are relatively small and triangular.[33] The wolf's head is large and heavy, with a wide forehead, strong jaws and a long, blunt muzzle.[35] The skull is 230–280 mm (9–11 in) in length and 130–150 mm (5–6 in) in width.[36] The teeth are heavy and large, making them better suited to crushing bone than those of other canids, though they are not as specialized as those found in hyenas.[37][38] Its molars have a flat chewing surface, but not to the same extent as the coyote, whose diet contains more vegetable matter.[39] Females tend to have narrower muzzles and foreheads, thinner necks, slightly shorter legs, and less massive shoulders than males.[40]

Adult wolves measure 105–160 cm (41–63 in) in length and 80–85 cm (31–33 in) at shoulder height.[35] The tail measures 29–50 cm (11–20 in) in length, the ears 90–110 mm (3+1⁄2–4+3⁄8 in) in height, and the hind feet are 220–250 mm (8+5⁄8–9+7⁄8 in).[41] The size and weight of the modern wolf increases proportionally with latitude in accordance with Bergmann's rule.[42] The mean body mass of the wolf is 40 kg (88 lb), the smallest specimen recorded at 12 kg (26 lb) and the largest at 79.4 kg (175 lb).[43][35] On average, European wolves weigh 38.5 kg (85 lb), North American wolves 36 kg (79 lb), and Indian and Arabian wolves 25 kg (55 lb).[44] Females in any given wolf population typically weigh 2.3–4.5 kg (5–10 lb) less than males. Wolves weighing over 54 kg (119 lb) are uncommon, though exceptionally large individuals have been recorded in Alaska and Canada.[45] In central Russia, exceptionally large males can reach a weight of 69–79 kg (152–174 lb).[41]

Pelage

The wolf has very dense and fluffy winter fur, with a short undercoat and long, coarse guard hairs.[35] Most of the undercoat and some guard hairs are shed in spring and grow back in autumn.[44] The longest hairs occur on the back, particularly on the front quarters and neck. Especially long hairs grow on the shoulders and almost form a crest on the upper part of the neck. The hairs on the cheeks are elongated and form tufts. The ears are covered in short hairs and project from the fur. Short, elastic and closely adjacent hairs are present on the limbs from the elbows down to the calcaneal tendons.[35] The winter fur is highly resistant to the cold. Wolves in northern climates can rest comfortably in open areas at −40 °C (−40 °F) by placing their muzzles between the rear legs and covering their faces with their tail. Wolf fur provides better insulation than dog fur and does not collect ice when warm breath is condensed against it.[44]

In cold climates, the wolf can reduce the flow of blood near its skin to conserve body heat. The warmth of the foot pads is regulated independently from the rest of the body and is maintained at just above tissue-freezing point where the pads come in contact with ice and snow.[46] In warm climates, the fur is coarser and scarcer than in northern wolves.[35] Female wolves tend to have smoother furred limbs than males and generally develop the smoothest overall coats as they age. Older wolves generally have more white hairs on the tip of the tail, along the nose, and on the forehead. Winter fur is retained longest by lactating females, although with some hair loss around their teats.[40] Hair length on the middle of the back is 60–70 mm (2+3⁄8–2+3⁄4 in), and the guard hairs on the shoulders generally do not exceed 90 mm (3+1⁄2 in), but can reach 110–130 mm (4+3⁄8–5+1⁄8 in).[35]

A wolf's coat colour is determined by its guard hairs. Wolves usually have some hairs that are white, brown, gray and black.[47] The coat of the Eurasian wolf is a mixture of ochreous (yellow to orange) and rusty ochreous (orange/red/brown) colours with light gray. The muzzle is pale ochreous gray, and the area of the lips, cheeks, chin, and throat is white. The top of the head, forehead, under and between the eyes, and between the eyes and ears is gray with a reddish film. The neck is ochreous. Long, black tips on the hairs along the back form a broad stripe, with black hair tips on the shoulders, upper chest and rear of the body. The sides of the body, tail, and outer limbs are a pale dirty ochreous colour, while the inner sides of the limbs, belly, and groin are white. Apart from those wolves which are pure white or black, these tones vary little across geographical areas, although the patterns of these colours vary between individuals.[48]

In North America, the coat colours of wolves follow Gloger's rule, wolves in the Canadian arctic being white and those in southern Canada, the U.S., and Mexico being predominantly gray. In some areas of the Rocky Mountains of Alberta and British Columbia, the coat colour is predominantly black, some being blue-gray and some with silver and black.[47] Differences in coat colour between sexes is absent in Eurasia;[49] females tend to have redder tones in North America.[50] Black-coloured wolves in North America acquired their colour from wolf-dog admixture after the first arrival of dogs across the Bering Strait 12,000 to 14,000 years ago.[51] Research into the inheritance of white colour from dogs into wolves has yet to be undertaken.[52]

Ecology

Distribution and habitat

Wolves occur across Eurasia and North America. However, deliberate human persecution because of livestock predation and fear of attacks on humans has reduced the wolf's range to about one-third of its historic range; the wolf is now extirpated (locally extinct) from much of its range in Western Europe, the United States and Mexico, and completely in the British Isles and Japan. In modern times, the wolf occurs mostly in wilderness and remote areas. The wolf can be found between sea level and 3,000 m (9,800 ft). Wolves live in forests, inland wetlands, shrublands, grasslands (including Arctic tundra), pastures, deserts, and rocky peaks on mountains.[2] Habitat use by wolves depends on the abundance of prey, snow conditions, livestock densities, road densities, human presence and topography.[39]

Diet

Like all land mammals that are pack hunters, the wolf feeds predominantly on ungulates that can be divided into large size 240–650 kg (530–1,430 lb) and medium size 23–130 kg (51–287 lb), and have a body mass similar to that of the combined mass of the pack members.[53][54] The wolf specializes in preying on the vulnerable individuals of large prey,[39] with a pack of 15 able to bring down an adult moose.[55] The variation in diet between wolves living on different continents is based on the variety of hoofed mammals and of available smaller and domesticated prey.[56]

In North America, the wolf's diet is dominated by wild large hoofed mammals (ungulates) and medium-sized mammals. In Asia and Europe, their diet is dominated by wild medium-sized hoofed mammals and domestic species. The wolf depends on wild species, and if these are not readily available, as in Asia, the wolf is more reliant on domestic species.[56] Across Eurasia, wolves prey mostly on moose, red deer, roe deer and wild boar.[57] In North America, important range-wide prey are elk, moose, caribou, white-tailed deer and mule deer.[58] Prior to their extirpation from North America, wild horses were among the most frequently consumed prey of North American wolves.[59] Wolves can digest their meal in a few hours and can feed several times in one day, making quick use of large quantities of meat.[60] A well-fed wolf stores fat under the skin, around the heart, intestines, kidneys, and bone marrow, particularly during the autumn and winter.[61]

Nonetheless, wolves are not fussy eaters. Smaller-sized animals that may supplement their diet include rodents, hares, insectivores and smaller carnivores. They frequently eat waterfowl and their eggs. When such foods are insufficient, they prey on lizards, snakes, frogs, and large insects when available.[62] Wolves in some areas may consume fish and even marine life.[63][64][65] Wolves also consume some plant material. In Europe, they eat apples, pears, figs, melons, berries and cherries. In North America, wolves eat blueberries and raspberries. They also eat grass, which may provide some vitamins, but is most likely used mainly to induce vomiting to rid themselves of intestinal parasites or long guard hairs.[66] They are known to eat the berries of mountain-ash, lily of the valley, bilberries, cowberries, European black nightshade, grain crops, and the shoots of reeds.[62]

In times of scarcity, wolves will readily eat carrion.[62] In Eurasian areas with dense human activity, many wolf populations are forced to subsist largely on livestock and garbage.[57] As prey in North America continue to occupy suitable habitats with low human density, North American wolves eat livestock and garbage only in dire circumstances.[67] Cannibalism is not uncommon in wolves during harsh winters, when packs often attack weak or injured wolves and may eat the bodies of dead pack members.[62][68][69]

Interactions with other predators

Wolves typically dominate other canid species in areas where they both occur. In North America, incidents of wolves killing coyotes are common, particularly in winter, when coyotes feed on wolf kills. Wolves may attack coyote den sites, digging out and killing their pups, though rarely eating them. There are no records of coyotes killing wolves, though coyotes may chase wolves if they outnumber them.[70] According to a press release by the U.S. Department of Agriculture in 1921, the infamous Custer Wolf relied on coyotes to accompany him and warn him of danger. Though they fed from his kills, he never allowed them to approach him.[71] Interactions have been observed in Eurasia between wolves and golden jackals, the latter's numbers being comparatively small in areas with high wolf densities.[35][70][72] Wolves also kill red, Arctic and corsac foxes, usually in disputes over carcasses, sometimes eating them.[35][73]

Brown bears typically dominate wolf packs in disputes over carcasses, while wolf packs mostly prevail against bears when defending their den sites. Both species kill each other's young. Wolves eat the brown bears they kill, while brown bears seem to eat only young wolves.[74] Wolf interactions with American black bears are much rarer because of differences in habitat preferences. Wolves have been recorded on numerous occasions actively seeking out American black bears in their dens and killing them without eating them. Unlike brown bears, American black bears frequently lose against wolves in disputes over kills.[75] Wolves also dominate and sometimes kill wolverines, and will chase off those that attempt to scavenge from their kills. Wolverines escape from wolves in caves or up trees.[76]

Wolves may interact and compete with felids, such as the Eurasian lynx, which may feed on smaller prey where wolves are present[77] and may be suppressed by large wolf populations.[78] Wolves encounter cougars along portions of the Rocky Mountains and adjacent mountain ranges. Wolves and cougars typically avoid encountering each other by hunting at different elevations for different prey (niche partitioning). This is more difficult during winter. Wolves in packs usually dominate cougars and can steal their kills or even kill them,[79] while one-to-one encounters tend to be dominated by the cat, who likewise will kill wolves.[80] Wolves more broadly affect cougar population dynamics and distribution by dominating territory and prey opportunities and disrupting the feline's behaviour.[81] Wolf and Siberian tiger interactions are well-documented in the Russian Far East, where tigers significantly depress wolf numbers, sometimes to the point of localized extinction.[82][77]

In Israel, Palestine, Central Asia and India wolves may encounter striped hyenas, usually in disputes over carcasses. Striped hyenas feed extensively on wolf-killed carcasses in areas where the two species interact. One-to-one, hyenas dominate wolves, and may prey on them,[83] but wolf packs can drive off single or outnumbered hyenas.[84][85] There is at least one case in Israel of a hyena associating and cooperating with a wolf pack.[86]

Infections

Viral diseases carried by wolves include: rabies, canine distemper, canine parvovirus, infectious canine hepatitis, papillomatosis, and canine coronavirus. In wolves, the incubation period for rabies is eight to 21 days, and results in the host becoming agitated, deserting its pack, and travelling up to 80 km (50 mi) a day, thus increasing the risk of infecting other wolves. Although canine distemper is lethal in dogs, it has not been recorded to kill wolves, except in Canada and Alaska. The canine parvovirus, which causes death by dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, and endotoxic shock or sepsis, is largely survivable in wolves, but can be lethal to pups.[87] Bacterial diseases carried by wolves include: brucellosis, Lyme disease, leptospirosis, tularemia, bovine tuberculosis,[88] listeriosis and anthrax.[89] Although lyme disease can debilitate individual wolves, it does not appear to significantly affect wolf populations. Leptospirosis can be contracted through contact with infected prey or urine, and can cause fever, anorexia, vomiting, anemia, hematuria, icterus, and death.[88]

Wolves are often infested with a variety of arthropod exoparasites, including fleas, ticks, lice, and mites. The most harmful to wolves, particularly pups, is the mange mite (Sarcoptes scabiei),[90] though they rarely develop full-blown mange, unlike foxes.[35] Endoparasites known to infect wolves include: protozoans and helminths (flukes, tapeworms, roundworms and thorny-headed worms). Most fluke species reside in the wolf's intestines. Tapeworms are commonly found in wolves, which they get though their prey, and generally cause little harm in wolves, though this depends on the number and size of the parasites, and the sensitivity of the host. Symptoms often include constipation, toxic and allergic reactions, irritation of the intestinal mucosa, and malnutrition. Wolves can carry over 30 roundworm species, though most roundworm infections appear benign, depending on the number of worms and the age of the host.[90]

Behaviour

Social structure

The wolf is a social animal.[35] Its populations consist of packs and lone wolves, most lone wolves being temporarily alone while they disperse from packs to form their own or join another one.[91] The wolf's basic social unit is the nuclear family consisting of a mated pair accompanied by their offspring.[35] The average pack size in North America is eight wolves and in Europe 5.5 wolves.[42] The average pack across Eurasia consists of a family of eight wolves (two adults, juveniles, and yearlings),[35] or sometimes two or three such families,[39] with examples of exceptionally large packs consisting of up to 42 wolves being known.[92] Cortisol levels in wolves rise significantly when a pack member dies, indicating the presence of stress.[93] During times of prey abundance caused by calving or migration, different wolf packs may join together temporarily.[35]

Offspring typically stay in the pack for 10–54 months before dispersing.[94] Triggers for dispersal include the onset of sexual maturity and competition within the pack for food.[95] The distance travelled by dispersing wolves varies widely; some stay in the vicinity of the parental group, while other individuals may travel great distances of upwards of 206 km (128 mi), 390 km (240 mi), and 670 km (420 mi) from their natal (birth) packs.[96] A new pack is usually founded by an unrelated dispersing male and female, travelling together in search of an area devoid of other hostile packs.[97] Wolf packs rarely adopt other wolves into their fold and typically kill them. In the rare cases where other wolves are adopted, the adoptee is almost invariably an immature animal of one to three years old, and unlikely to compete for breeding rights with the mated pair. This usually occurs between the months of February and May. Adoptee males may mate with an available pack female and then form their own pack. In some cases, a lone wolf is adopted into a pack to replace a deceased breeder.[92]

Wolves are territorial and generally establish territories far larger than they require to survive assuring a steady supply of prey. Territory size depends largely on the amount of prey available and the age of the pack's pups. They tend to increase in size in areas with low prey populations,[98] or when the pups reach the age of six months when they have the same nutritional needs as adults.[99] Wolf packs travel constantly in search of prey, covering roughly 9% of their territory per day, on average 25 km/d (16 mi/d). The core of their territory is on average 35 km2 (14 sq mi) where they spend 50% of their time.[98] Prey density tends to be much higher on the territory's periphery. Wolves tend to avoid hunting on the fringes of their range to avoid fatal confrontations with neighbouring packs.[100] The smallest territory on record was held by a pack of six wolves in northeastern Minnesota, which occupied an estimated 33 km2 (13 sq mi), while the largest was held by an Alaskan pack of ten wolves encompassing 6,272 km2 (2,422 sq mi).[99] Wolf packs are typically settled, and usually leave their accustomed ranges only during severe food shortages.[35] Territorial fights are among the principal causes of wolf mortality, one study concluding that 14–65% of wolf deaths in Minnesota and the Denali National Park and Preserve were due to other wolves.[101]

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Grey_wolf

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk