A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| |

China |

New Zealand |

|---|---|

| Diplomatic mission | |

| Chinese Embassy, Wellington | New Zealand Embassy, Beijing |

| Envoy | |

| Ambassador Wang Xiaolong[1] | Ambassador Clare Fearnley[2] |

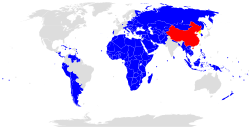

The China–New Zealand relations, sometimes known as Sino–New Zealand relations, are the relations between China and New Zealand. New Zealand recognised the Republic of China after it lost the Chinese Civil War and retreated to Taiwan in 1949, but switched recognition to the People's Republic of China on 22 December 1972.[3][4] Since then, economic, cultural, and political relations between the two countries have grown over the past four decades. China is New Zealand's largest trading partner in goods and second largest trading partner in services. In 2008, New Zealand became the first developed country to enter into a free trade agreement with China.[5] In recent years, New Zealand's extensive economic relations with China have been complicated by its security ties to the United States.

In addition to formal diplomatic and economic relations, there has been significant people–to–people contact between China and New Zealand. Chinese immigration to New Zealand dates back to the gold rushes and has substantially increased since the 1980s.[6]

History

Qing dynasty China

New Zealand's contact with China started in the mid 19th century. The first records of ethnic Chinese in New Zealand were migrant workers from Guangdong province, who arrived during the 1860s Otago Gold Rush. Most of the migrant workers were male, with few women migrants. Emigration from China was driven by overpopulation, land shortages, famine, drought, banditry, and peasant revolts, which triggered a wave of Chinese migration to Southeast Asia, Australia, New Zealand, the United States, and Canada.[7]

Early Chinese migrants encountered considerable racial discrimination and prejudice. In 1871, the New Zealand Government imposed a poll tax on Chinese migrants that was not repealed until 1944. Other discriminatory policies included an English literacy test, restrictive immigration measures, denial of old age pensions, and being barred from permanent residency and citizenship (from 1908 to 1952). After the Gold Rush ended in the 1880s, many of the former Chinese miners found work as market gardeners, shopkeepers, and laundry operators. There was some limited intermarriage with White and indigenous Māori women.[8][9]

Republic of China, 1912–1949

In 1903, the Qing dynasty had established a consulate in Wellington to deal with trade, immigration, and local Chinese welfare. Following the Xinhai Revolution in 1912, the Republic of China took over the consulate. The lack of a reciprocal New Zealand mission in China made the Republic of China's mission in Wellington serve as the primary point of contact between both governments until 1972.[10] During the Republican era, New Zealand interests in China were largely represented by British diplomatic and consular missions. However, there were some attempts to establish New Zealand trade commissions in Tianjin and Shanghai.[11]

Between 1912 and 1949, there were over 350 New Zealand expatriates living and working in China, including missionaries for various Christian denominations, medical workers, United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) workers, teachers, and telegraph workers. Some notable expatriates included the missionaries Annie James and James Huston Edgar, and the communist writer, teacher, and activist Rewi Alley.[12]

During the Second World War, New Zealand society developed a more favourable view of China because of its status as a wartime ally against Japan. Chinese market gardeners were viewed as an important contribution to the wartime economy. New Zealand also eased its immigration policy to admit Chinese refugees and grant them permanent residency. In the postwar years, many Chinese migrants, including women and children, settled in New Zealand since the Communist victory in 1949 made it difficult for many to return home.[13]

Cold War tensions, 1949–1972

Following the establishment of the People's Republic of China (PRC) in 1949, New Zealand did not initially recognise the new government. Instead, it joined Australia and the United States in continuing to recognise the Republic of China (ROC) government, which had relocated to Taiwan, as the legitimate government of China. Between 1951 and 1960, New Zealand and Australia consistently supported a US moratorium proposal to block Soviet efforts to seat the PRC as the lawful representatives of China in the United Nations and to expel the ROC representatives. By contrast, the United Kingdom had established diplomatic relations with the PRC in 1949. While the conservative National Party favoured the ROC, the social democratic Labour Party favoured extending diplomatic relations to the PRC. New Zealand and the PRC also fought on opposite sides during the Korean War, with the former supporting the United Nations forces and the latter backing North Korea.[14][15]

The PRC government also expelled many missionaries and foreigners, including most New Zealand expatriates by 1951. One missionary, Annie James of the New Zealand Presbyterian Church's Canton Villages Mission, was imprisoned and interrogated. However, some pro-communist Westerners, including Rewi Alley, were allowed to remain in China. Alley pioneered a working model for secular "cooperative education" in vocational subjects and rural development. Despite the lack of official relations between the two countries, unofficial relations were conducted through the auspices of the Chinese People's Association for Friendship with Foreign Countries and the New Zealand China Friendship Society (NZCFS). In addition, the Communist Party of New Zealand and some trade unions were sympathetic to the PRC rather than the Soviet Union.[16][17]

In 1955 Warren Freer (then an opposition Labour MP) was the first Western politician to visit China, against the wishes of Labour leader Walter Nash but with the encouragement of Prime Minister Sidney Holland.[18]

New Zealand photographer Brian Brake was given irregular access to China in 1957 and 1959, photographing Nikita Khrushchev's visit to the country, members of the PRC government like Chairman Mao Zedong, and scenes of life around the country at the time. Brake was the only Western photojournalist who documented the 10th anniversary of the People's Republic of China.[19]

Prime Minister of New Zealand Keith Holyoake visited ROC President Chiang Kai-shek in 1960. Holyoake had a favourable view of the ROC and permitted the upgrading of the ROC consulate to full embassy status in 1962. However, New Zealand declined to establish any diplomatic or trading mission in Taiwan but opted to conduct its relations with the ROC through trade commissioners based in Tokyo and Hong Kong. As pressure for PRC representation at the United Nations grew, the New Zealand Government came to favour dual representation of both Chinese governments, but that was rejected by both the ROC and the PRC. In 1971, New Zealand and other US allies unsuccessfully opposed United Nations General Assembly Resolution 2758 to recognise the PRC as the "only legitimate representative of China to the UN."[20][21]

People's Republic of China, 1971–present

In 1971, 78 countries invited Chinese table tennis teams to tour, and New Zealand was the sixth nation's invitation accepted, for a tour in July 1972. The Chinese delegation arrived in Auckland, then flew to Wellington on Monday 17 July where they were met by protesters advising them to defect. They played in the Lower Hutt Town Hall. The following day an official afternoon tea reception was attended by the Prime Minister Jack Marshall, half the cabinet, Labour leader Norman Kirk, Wellington Mayor Frank Kitts, and Bryce Harland who was soon to be our first Ambassador to China. A tour followed, to the farm of former All Black Ken Gray at Pauatahanui where they watched sheep shearing and sheep dogs.[22]

On 22 December 1972, the newly elected Third Labour Government formally recognised the People's Republic of China, with both governments signing a Joint Communique to govern bilateral relations. According to former New Zealand diplomat Gerald Hensley, Prime Minister Norman Kirk initially hesitated recognising the PRC until his second term but changed his mind because of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Kirk was influenced by his Australian counterpart Gough Whitlam's decision to recognise the PRC.[23][24][25]

Despite ending diplomatic relations with the ROC, the New Zealand Permanent Representative to the UN negotiated an agreement with his ROC counterpart Huang Hua for both countries to continue maintaining trade and other non-official contacts with Taiwan. The last ROC Ambassador to New Zealand was Konsin Shah, the dean of the diplomatic corps in Wellington.[26][27]

In April 1973, Joe Walding became the first New Zealand government minister to visit China and met Premier Zhou Enlai. In return, Chinese Foreign Trade Minister Bai Xiangguo visited Wellington, seeking to sign a trade agreement in New Zealand. The same year, the PRC established an embassy in Wellington, and Pei Tsien-chang was appointed as the first Chinese ambassador to New Zealand. In September 1973, the New Zealand Embassy was established in Beijing with Bryce Harland serving as the first New Zealand Ambassador to China.[27][28]

Following the 1975 general election, the Third National Government abandoned National's support for the "Two Chinas policy" and expanded upon its Labour predecessors' diplomatic and trade relations with the PRC.[27][29] In April–May 1976, Robert Muldoon became the first New Zealand Prime Minister to visit China. He visited Beijing and met with Premier Hua Guofeng and Mao, being one of the last foreign leaders to meet the Chairman before he passed in July. Muldoon's visit served to strengthen diplomatic and trading ties between the two countries, and to reassure the New Zealand public that China did not pose a threat to New Zealand.[30]

Since the end of the Cold War, bilateral relations between New Zealand and China have grown particularly in the areas of trade, education, tourism, climate change, and public sector co-operation. Bilateral relations has been characterized by trade and economic co-operation. In August 1997, New Zealand became the first Western country to support China's accession to the World Trade Organization by concluding a bilateral agreement. In April 2004, New Zealand became the first country to recognise China as a market economy during a second round of trade negotiations. In November 2004, New Zealand and China launched negotiations towards a free trade agreement in November 2004, with an agreement being signed in April 2008. In November 2016, both countries entered into negotiations to upgrade their free trade agreement.[5][31]

Cultural relations

China and New Zealand have a long history of people–to–people contacts. During the 19th century, migrants migrated to New Zealand to work as miners. Despite racial prejudice and anti-immigrant legislation, a small number still settled down to work as market gardeners, businessmen, and shopkeepers. Following World War II, official and public attitudes and policies towards Chinese migrants were relaxed and more Chinese women and children were allowed to settle. During the post-war years, the Chinese population in New Zealand increased with many becoming middle-class professionals and businessmen.[6]

In 1987, the New Zealand Government abandoned its long-standing preference for British and Irish immigrants in favour for a skills-based immigration policy. By 2013, the Chinese New Zealander population had increased to 171,411, comprising 4% of the country's population. Within this group, three-quarters were foreign-born and only one-quarter were locally-born. Of the foreign-born population, 51% came from China, 5% from Taiwan, and 4% from Hong Kong.[32]

In addition, several New Zealand missionaries, businessmen, aid workers, and telegraph workers have lived and worked in China as long-term residents.[12] One notable New Zealand expatriate in China was Rewi Alley, a New Zealand-born writer, educator, social reformer, potter, and member of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). He lived and worked in China for 60 years until his death in 1987. He came to symbolise the important role of people to people contacts in building good relations and accentuating common ground between countries as different as New Zealand and China. In 1997, the 100th anniversary of Alley's birth was marked by celebrations in Beijing and New Zealand.[33][34][35][36]

In an effort to build cultural relations between Maori and Chinese, New Zealand has increasingly utilised a "taniwha and dragon" framework. In 2013, the Taniwha and Dragon Festival, organized in part by the minister of Māori affairs, Pita Sharples, was held at Orakei Marae in Auckland to commemorate historical interactions between Māori and Chinese migrants in New Zealand.[37] Later, it was used to connect iwi businesses with Chinese counterparts, such as the 'Taniwha Dragon’ economic summit that was held in the city of Hastings in 2017. More recently, it has been used by New Zealand's foreign minister, Nanaia Mahuta, to conceptutalise Sino-New Zealand relations more broadly.[38]

Economic relations

Trade

In 1972, New Zealand's trade relations with mainland China were paltry with NZ exports to China estimated to being less than NZ$2 million per annum. Early New Zealand exports to China included timber, pulp and paper while early Chinese exports to NZ were high-quality printing paper and chemicals.[39][40] Over the successive decades, trade between the two countries grew. In terms of the Chinese share of New Zealand trade, New Zealand's exports to China rose from about 2% in 1981 to about 4.9% in 1988. In 1990, it dropped to 1% due to the fallout from the Tiananmen Square massacre. By 2001, NZ exports to China accounted for 7% of China's New Zealand's overseas trade. Meanwhile, New Zealand imports to China rose from below 1% of New Zealand's trade volume in 1981 to 7% by 2001.[41]

Mainland China (i.e. excluding Hong Kong and Macau) is New Zealand's largest trading partner, with bilateral trade between the two countries in 2017-18 valued at NZ$27.75 billion. Hong Kong SAR is New Zealand's 13th-largest trading partner, with bilateral trade of NZ$2.1 billion.[42]

New Zealand's main exports to China are dairy products, travel and tourism, wood and wood products, meat, fish and seafood, and fruit. China's main exports to New Zealand are electronics, machinery, textiles, furniture, and plastics.[43][42]

Free trade agreement

A free trade agreement (FTA) between China and New Zealand was signed on 7 April 2008 by Premier of the People's Republic of China Wen Jiabao and Prime Minister of New Zealand Helen Clark in Beijing.[44] Under the agreement, about one third of New Zealand exports to China will be free of tariffs from 1 October 2008, with another third becoming tariff free by 2013, and all but 4% by 2019.[44] In return, 60% of China's exports to New Zealand will become tariff free by 2016 or earlier; more than a third are already duty-free.[45] Investment, migration, and trade in services will also be facilitated.[46]

The free trade agreement with China is New Zealand's most significant since the Closer Economic Relations agreement with Australia was signed in 1983. It was also the first time China has entered into a comprehensive free trade agreement with a developed country.[47]

The agreement took more than three years to negotiate. On 19 November 2004 Helen Clark and President of the People's Republic of China, Hu Jintao announced the commencement of negotiations towards an FTA at the APEC Leaders meeting in Santiago, Chile. The first round of negotiations was held in December 2004. Fifteen rounds took place before the FTA was signed in April 2008.[48]

While the FTA enjoys the support of New Zealand's two largest political parties, Labour and National, other parties such as the Green Party and the Māori Party opposed the agreement at the time.[49] Winston Peters was also a vocal opponent of the agreement, but agreed not to criticise it while acting as Minister of Foreign Affairs overseas (a position he held from 2005 to 2008).[50]

In early November 2019, New Zealand and China agreed to upgrade their free trade agreement. China has eased restrictions on New Zealand exports and given New Zealand preferential access to the wood and paper trade with China. In return, New Zealand agree to lessen visa restrictions for Chinese tour guides and Chinese language teachers.[51][52]

On 26 January 2021, New Zealand and China signed a deal to upgrade their free trade agreement to give New Zealand exports greater access to the Chinese market, eliminating or reducing tariffs on New Zealand exports such as dairy, timber, and seafood as well as compliance costs.[53]

On 1 January 2024, China lifted all tariffs on New Zealand dairy imports including milk powder as part of the NZ-China free trade agreement. This development was welcomed by Minister of Trade and Agriculture Todd McClay, who said that it would bring NZ$330 million worth of revenue to the New Zealand economy.[54]

Film cooperation

In May 2015, The Hollywood Reporter reported that several Chinese, New Zealand, and Canadian film companies including the China Film Group, the Qi Tai Culture Development Group, New Zealand's Huhu Studios, and the Canadian Stratagem Entertainment had entered into a US$800 million agreement to produce 17 live-action and animated films over the next six to eight years. As part of the agreement, the China Film Group's animation division China Film Animation would be working with Huhu Studios to produce an animated film called Beast of Burden with a US$20 million budget.[55] This partnership between Huhu Studios and China Film Animation was the first official New Zealand–Chinese film co-production agreement. The film was subsequently released as Mosley on 10 October 2019.[56][57]

Education relations

China and New Zealand have a history of education links and exchanges, including bilateral scholarship programmes and academic cooperation. There was a dramatic expansion in student flows and other engagement in the late 1990s. During the 1990s, the number of Chinese nationals studying at public tertiary institutions in New Zealand rose from 49 in 1994, 89 in 1998, 457 in 1999, 1,696 in 2000, 5,236 in 2001, and 11,700 in 2002. The percentage of full fee paying Asian students from China at public tertiary institutions also rose from 1.5% in 1994 to 56.3% by 2002. The increase in Chinese international students in New Zealand accompanied the increase in the percentage of international students at New Zealand universities and polytechnics.[58]

Between 2003 and 2011, the number of Chinese students studying in New Zealand dropped from 56,000 to about 30,000 by 2011. In 2003, Chinese students accounted for 46% of all international students in New Zealand. By 2011, this figure had dropped to 25%.[59] As of 2017, China was the largest source of international students in New Zealand. In 2017, there were over 40,000 Chinese student enrollments in New Zealand.[5]

In 2019 Chinese Vice Consul General Xiao Yewen intervened at Auckland University of Technology in relation to an event marking the 30th Anniversary of the Tiananmen Square massacre. AUT cancelled the booking for the event and it went ahead at a council-owned facility.[60]

Diplomatic relations

People's Republic of China

New Zealand is represented in China through the New Zealand Embassy in Beijing, with consulates in Shanghai, Guangzhou, Hong Kong and Chengdu.[61] The Chengdu Consulate-General was opened by New Zealand Prime Minister John Key in November 2014.[62][63] China is represented in New Zealand through the Embassy of the People's Republic of China in Wellington, with consulates in Auckland and Christchurch.[64][65][66]

Hong Kong

In addition to its diplomatic relations with mainland of China, New Zealand also maintains diplomatic and economic relations with the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. In March 2010, New Zealand and Hong Kong entered into a bilateral economic partnership agreement. New Zealand maintains a Consulate-General in Hong Kong, which is also accredited to the Macau SAR. Hong Kong's interests in New Zealand are represented by the Chinese Embassy in Wellington and the Hong Kong Economic and Trade Office in Sydney.[67][68]

Republic of China (Taiwan)

Though New Zealand no longer has diplomatic relations with Taiwan, New Zealand still maintains trade, economic, and cultural relations with Taiwan. Taiwan has two Economic and Cultural offices in Auckland and Wellington. New Zealand also has a Commerce and Industry Office in Taipei.[69][70]

State visits

Chinese tours by New Zealand delegates and ministers

New Zealand Ministerial Visits to the People's Republic of China:[5]

| Dates | Minister/Delegate | Cities visited | Reason |

|---|---|---|---|

| April 2008[71] | Prime Minister of New Zealand, Rt Hon Helen Clark | Beijing | Official visit |

| November 2007 | Minister of Foreign Affairs, Winston Peters | Official visit | |

| September 2007 | Deputy Prime Minister, Dr Michael Cullen | Official visit | |

| August 2007 | Minister of Customs and Youth Affairs, Nanaia Mahuta | Official visit | |

| July 2007 | Minister of State, Dover Samuels | Official visit | |

| May 2007 | Minister of Foreign Affairs, Winston Peters | Official visit | |

| April 2007 | Minister of Civil Aviation; Minister of Police, Annette King | Official visit | |

| March 2007 | Minister of Communications & IT, David Cunliffe | Official visit | |

| December 2006 | Minister of Food Safety & Minister of Police, Annette King | Official visit | |

| November 2006 | Minister for Trade Negotiations & Minister of Defence, Phil Goff | Official visit | |

| November 2006 | Minister of Tourism, Damien O'Connor | Official visit | |

| April 2006 | Minister of State, Jim Sutton | Beijing | Official visit |

| July 2005 | Minister for Trade Negotiations, Jim Sutton | Beijing | Official visit |

| June 2005 | Minister for Trade Negotiations, Jim Sutton | Beijing | Official visit |

| May 2005 | Prime Minister of New Zealand, Rt Hon Helen Clark | Beijing | Official visit |

| February 2005 | Minister of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Phil Goff | Beijing | Official visit |

| September 2004 | Minister of Health, Annette King | Beijing | Official visit |

| August 2004 | Minister for Research, Science and Technology, Pete Hodgson | Various | Official visit |

| February 2004 | Minister for Trade Negotiations, Minister of Agriculture, Minister of Forestry, Jim Sutton | Various | Official visit |

| September 2003 | Speaker of the House of Representatives, Jonathan Hunt | Beijing | Led a parliamentary delegation to China |

| September 2003 | Minister of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Phil Goff | Beijing | Official visit |

| September 2003 | Minister of Education, Trevor Mallard | Various | Official visit |

| December 2002 | Minister for Trade Negotiations, Minister of Agriculture, Minister of Forestry, Jim Sutton | Various | Official visit |

| May 2002 | Minister of Education, Trevor Mallard | Various | Official visit |

| April 2002 | Graham Kelly and four other MPs | Tibet | Official visit |

| March 2002 | Minister for Trade Negotiations, Minister of Agriculture, Minister of Forestry, Jim Sutton | Various | Official visit |

| October 2001 | Prime Minister of New Zealand, Rt Hon Helen Clark | Beijing | Official visit |

| April 2001 | Prime Minister of New Zealand, Rt Hon Helen Clark | Beijing | Official visit |

| November–December 2000 | Governor-General of New Zealand, Sir Michael Hardie Boys | Beijing | Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=China–New_Zealand_relations