A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Part of a series on Shia Islam |

| Twelver Shi'ism |

|---|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Conservatism in Iran |

|---|

|

The Guardianship of the Islamic Jurist (Persian: ولایت فقیه, romanized: Velâyat-e Faqih, also Velayat-e Faghih; Arabic: وِلاَيَةُ ٱلْفَقِيهِ, romanized: Wilāyat al-Faqīh) is a concept in Twelver Shia Islamic law which holds that until the reappearance of the "infallible Imam" (sometime before Judgement Day), at least some of the "religious and social affairs" of the Muslim world should be administered by righteous Shi'i jurists (Faqīh).[1] Shia disagree over whose "religious and social affairs" are to be administered and what those affairs are.[2]

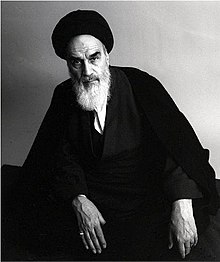

Wilāyat al-Faqīh is associated in particular with Ruhollah Khomeini[3] and the Islamic Republic of Iran. In a series of lectures in 1970, Khomeini advanced the idea of guardianship in its "absolute" form as rule of the state and society. This version of guardianship now forms the basis of the Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran, which calls for a Guardian Jurist (Vali-ye Faqih, Arabic: وَلِيُّةُ فَقِيهٌ, romanized: Waliy Faqīh), to serve as the Supreme Leader of that country.[4][5]

Under the "absolute authority of the jurist" (Velayat-e Motlaqaye Faqih), the jurist/faqih has control over all public matters including governance of states, all religious affairs including the temporary suspension of religious obligations such as the salat prayer or hajj pilgrimage.[6][3] Obedience to him is more important (according to proponents) than performing those religious obligations.[7]

Other Shi'i Islamic scholars disagree, with some limiting guardianship to a much narrower scope[2]—things like mediating disputes,[8] and providing guardianship for orphaned children, the mentally incapable, and others lacking someone to protect their interests.[9]

There is also disagreement over how widely supported Khomeini's doctrine is; that is, whether "the absolute authority and guardianship" of a high-ranking Islamic jurist is "universally accepted amongst all Shi’a theories of governance" and forms "a central pillar of Imami political thought" (Ahmed Vaezi, Mohammad-Taqi Mesbah-Yazdi),[10] or whether there is no consensus in favor of the model of the Islamic Republic of Iran, neither among the public in Iran (Alireza Nader, David E Thaler, S. R. Bohandy),[11] nor among most religious leaders[12] in the leading centers of Shia thought (i.e. Qom and Najaf), (Ali Mamouri).[13]

Terminology

Arabic and Persian

Arabic language phrases associated with Guardianship of the Jurist, such as Wilāyat al-Faqīh, Wali al-Faqīh, are widely used, Arabic being the original language of Islamic sources such as the Quran, hadith, and much other literature. However, the Persian language translation, Velayat-e Faqih, Vali-e-faqih are also commonly used in discussion about the concept and practice in Iran, which is both the largest Shi'i majority country, and as the Islamic Republic of Iran, is also the one country in the world where Wilāyat al-Faqīh is part of the structure of government.

Meaning, definitions

Wilāyat al-Faqīh/velayat-e faqih is often used to mean Ayatollah Khomeini's vision of velayat-e faqih as essential to Islamic government, giving no further qualification, with those supporting limited non-governmental guardianship of faqih, being described as "rejecting" velayat-e faqih.[14][note 1] This is common particularly outside of scholarly and religious discussion, and among supporters (e.g. Muhammad Taqi Misbah Yazdi).[15] In more religious, scholarly, and precise discussion, terminology becomes more involved.

Wilayat conveys several meanings which are involved in Twelver Islamic history. Morphologically, Wilāyat is derived from the Arabic verbal root "w-l-y", Wilaya, meaning not only "to be in charge", but “to be near or close to someone or something",[10] to be a friend, etc.[16]

Meanings of Wilayat include: rule, supremacy or sovereignty, "guardianship" or "authority",[17] "guardianship, mandate, governance and rulership" [note 2] or "governorship" or "province".[25] In another sense, Wilayat means friendship, loyalty, or guardianship (see Wali).[26][note 3]

In Islam, jurists or experts in Islamic jurisprudence are Faqīh, (plural Fuquaha).[1]

For those who support a government based on rule of a faqih, Wilāyat al-Faqīh has been translated as "rule of the jurisconsult," "mandate of the jurist," "governance of the jurist", "the discretionary authority of the jurist".[29] More ambiguous translations are "guardianship of the jurist", "trusteeship of the jurist".[30] (Shaykh Murtadha al-Ansari and Abu al-Qasim al-Khoei, for example, would talk of the "guardianship of the jurisprudent", not "the mandate of the jurisprudent".)[29]

Some definitions of uses of the term “Wilayat” (not necessarily involving jurists) in Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh) terminology (or at least Twelver terminology) are:

- Wilayat al-Qaraba—authority (Wilayat) given to a father or paternal grandfather over minors and the mentally ill.[10]

- Wilayat al-Qada’—authority given to a just and capable faqih during the absence of the Imam to judge "amongst the people based upon God's law and revelation", and collect Islamic taxes/tithes (zakat, sadaqa, kharaj).[10]

- Wilayat al-Hakim—the guardian of those who have no guardian; authority given to a regular administrator of justice (hakim), to supervise the interests of a person who does not have a natural guardian and who is unable to take care of his own affairs; such as a mentally ill or mentally disabled person.[10]

- Wilayat al-Usuba—authority over administration of inheritance, and rights of inheritors in Sunni fiqh. (This authority is "not accepted by Imami scholars".)

Regarding jurist involvement in governance, definitions include:

- Wilayat al-Mutlaqa (absolute rule/authority, الولایه المطلقه) of the supreme faqih/jurisprudent, also transliterated as Velayat-e motlagh-e faghih, Velayat-e motlaqeh-ye faqıh,[31] also called Wilayat al- Mutlaqa al-Elahiya,[10]

- has been defined as discretionary authority bestowed on the prophet Muhammad and on the Imams (Ahmed Vaezi);[10]

- has been defined (by the Ayatollah Khomeini circa 1988), to mean that the Islamic state has the religious mandate to suspend, if not revoke, substantive divine ordinances (ahkam-e far‘ıyeh-ye elahıyeh) such as hajj or fasting if sees the need to;[31]

- it has also been used (by Iranian conservatives circa 2010) to mean that at least in the case of the Islamic Republic of Iran, the head faqih has "the absolute right to make decisions for the state", notwithstanding the desires of any elected office holders or institutions or the general public.[32] It is a "new term", applied by Khomeini "publicly", in 1990 when it "was enshrined in the constitution of Islamic Iran".[33]

- Wilayat al-Muqayada ("conditional" authority" of the faqih/jurisprudent) "restricts the right of the faqih for issuing governmental orders" to "permissibility cases" (mubahat), which must not be "in opposition" to "obligatory Islamic laws.[33]

- Wilayat al-Amma ("universal authority" of the faqih/jurisprudent). Supporters of this concept believe orders given by a jurist holder of "wilayat al-amma" are not restricted "to merely the administration of justice". They "may issue orders" which are "incumbent upon all Muslims, even other fuqaha, to obey".[33] They have the "right and duty to lead the Shi’a community and undertake the full function and responsibilities of an infallible Imam".[10] This is "the highest form of authority (Wilayat) bestowed upon the faqih" according to at least one cleric (Ahmed Vaezi).[note 4]

- Wilayat al-Siyasiyya—political authority, is one of the elements included in Wilayat al-amma.[10]

- Wilayat at-Takwiniyyah (ontological guardianship). According to Muhammad Taqi Misbah Yazdi, ontological guardianship is "having authority over the entire universe and the rules governing it is basically related to God". This great power was granted by God "to the Prophet of Islam (S) and the infallible Imams (‘a)" and explains why they and certain other "saints" can perform miracles.[34]

- Wilayat at-Tashri‘iyyah (legislative guardianship) Also a term used by Muhammad Taqi Misbah Yazdi, is guardianship involving the "management of society", "which concerns the Prophet (S) and the infallible Imams (‘a)" and with Khomeini's system the ruling guardian jurist.[34]

The term "mullahocracy" (rule by mullahs, i.e. by Islamic clerics) has been used as a pejorative term to describe Wilāyat al-Faqīh as government and specifically the Islamic Republic of Iran.[35][36]

History

Early Islam

A foundational belief of Twelver Shi'ism is that the spiritual and political successors of (the Islamic prophet) Muhammad are not caliphs (as Sunni Muslims believe), but the "Imams"—a line starting with Muhammad's cousin, son-in-law and companion, Ali (died 661 CE), and continuing with his male descendants. Imams were almost never in a position to rule territory, but did have the loyalty of their followers and delegated some of their functions, to "qualified members" of their community, "particularly in the judicial sphere".[3] In the late 9th century (873-874 CE) the Twelfth Imam, a boy at the time, is reported to have mysteriously disappeared. Historians believe that Shi'i jurists "responded by developing the idea" of the "occultation",[37] whereby the 12th Imam was still alive but had "been withdrawn by God from the eyes of people" to protect his life until conditions were ripe for his reappearance.[37]

As the centuries have gone by and the wait continues (the Hidden Imam's "life has been miraculously prolonged"),[38] the Shi'i community (ummah), has had to determine who, if anyone, has his authority (wilayah) for what functions during the Imam's absence.[17] The delegation of some functions—for example, the collection and disbursement of religiously mandated tithes (zakat and khums) — continued during occultation,[3] but others were limited. Shi'i jurists, and especially al-Sharif al-Murtada (d. 1044 CE), forbade[17] "waging of offensive jihad or (according to some jurists) the holding of Friday prayers",[3] as this power was in abeyance (saqit) until the return of the Imam.[17] Al-Murtada also excluded implementing the penal code (hudud), leading the community in jihad, and giving allegiance to any leader.[17]

For many centuries, according to at least two historians (Moojan Momen, Ervand Abrahamian), Shia jurists have tended to stick to one of three approaches to the state: cooperated with it, trying to influence policies by becoming active in politics, or most commonly, remaining aloof from it.[39][note 5]

One firm supporter of governance by jurist -- Mohammad-Taqi Mesbah-Yazdi—describes the arrival of rule of jurist in Iran as a "revolution" after fourteen centuries of "lamentable" governance in the Islamic world.[41] Other supporters (Ahmed Vaezi) insist that the idea that the governance by jurist is "new", is erroneous. Vaezi maintains it is the logical conclusion of arguments made by high-level Shia faqih of medieval times who argued that high-level Shia faqih be given authority, although their use of Taqiya (precautionary dissimulation) prevents this from being obvious to us.[42]

A significant event in Islamic and especially Shia history was the rise of the Safavid dynasty (1501–1702), which at its height ruled a vast area including modern day Iran and beyond.[note 6] The Safavids forcibly converting Iran's population to the state religion of Twelver Shi'ism,[47][48][49][50] (which continues to be the religion of a large majority of its population). According to Hamid Algar, (a convert to Islam and supporter of Ruhollah Khomeini), under the Safavids, the general deputyship "occasionally was interpreted to include all the prerogatives of rule that in principle had belonged to the imams, but no special emphasis was placed on this." And in the nineteenth century, velayat-e faqih began "to be discussed as a distinct legal topic".[3]

There are other theories by supporters of absolute Wilāyat al-Faqīh of when the doctrine was first advocated or practiced, or at least early examples of it. One argument is that was probably first introduced in the fiqh of Ja'far al-Sadiq (d.765) in the famous textbook Javaher-ol-Kalaam (جواهر الکلام).[citation needed]

The issue was reportedly mentioned by the earliest Shi'i mujtahids such as al-Shaykh Al-Mufid (948–1022), and enforced for a while by Muhaqqiq Karaki during the era of Tahmasp I (1524–1576).[citation needed]

Iranian cleric Mohammad Mahdee Naraqi, or at least his son Molla Ahmad Naraqi (1771-1829 C.E.), are said to have argued that "the scope of wilayat al-faqıh extends to political authority",[29] more than a century earlier than Khomeini,[29] and over all aspects of a believer's personal life, but never tried to establish or preach for the establishment of a state based on wilayat al-faqıh al-siyasıyah (the divine mandate of the jurisprudent to rule).[51][note 7][note 8] Ahmad Naraqi insisted on the absolute guardianship of the jurist over all aspects of a believer's personal life, but he did not claim jurist's authority over public affairs nor present Islam as a modern political or state system. Nor did he pose any challenge to Fath Ali Shah Qajar, obediently declaring jihad against Russia for the Russo-Persian War (1826–1828), which Iran lost.[52] According to Moojan Momen, "the most" that Naraqi or any Shi'i prior to Khomeini "have claimed is that kings and rulers should be guided in their actions and politics by the Shi'i faqih ..."[54] Naraqi's concept was not passed on by his most famous student, the great Shi'ite jurist Ayatullah Shaykh Murtaza Ansari, who argued against absolute authority of the jurist over all affairs of a believer's life.[52]

However, according to John Esposito in The Oxford Dictionary of Islam, the first Islamic scholar to advance the theory of the Guardianship of the Islamic Jurist (and who "developed a notion of 'rule of the jurist'") came much later -- Morteza Ansari (~1781–1864).[55] Mohamad Bazzi dates "the concept of wilayat al-faqih" as a model "of political rule" from "the early nineteenth century".[56]

A doctrinal change in most of Twelver Shiism (and particularly Iran) in the late 18th century that gave Shi'i ulama the power to use of ijtihad (i.e., reasoning) in the creation of new rules of fiqh, exclude hadith they considered unreliable, and declaring it obligatory to for non-faqih Muslims (i.e. almost all Muslims) to obey a mujtahid when seeking to determine Islamically correct behavior; was the triumph of the Usuli school of doctrine over the Akhbari school.[57]: 127 [note 9] But along with this doctrinal power came political, economic and social power -- control by the ulama over activities left to the government in modern states — the clergy "directly collected and dispersed" the zakat and khums taxes, had "huge" waqf mortmains (religious foundations) as well as personal properties, "controlled most of the dispensing of justice", were "the primary educators, oversaw social welfare, and were frequently courted and even paid by rulers"[59][60] — but meant that as the nineteenth century progressed "important ulama" and their allies in the bazaar (the traditional commercial and banking sector) came into conflict with the secular authorities, specifically the shah.

Colonial and post-colonial era

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, there were two major instances of jurist involvement in politics in Iran, (which continued to be the largest Shia-majority state and went on to be a major petroleum exporter).[61]

- A fatwa in 1891 by Mirza Shirazi declaring tobacco forbidden, successfully undermining the overly generous 1890 tobacco concession granted to British imperialists by the monarch of Persia;[note 10] and

- the support by Marja' Muhammad Kazim Khurasani (see below), for the democratic Persian Constitutional Revolution of 1905–1911.[note 11]

The Tobacco Protest and Constitutional Revolution (and not the Islamic revolution), have been described both as

- exceptions to apolitical stance of leading Shia jurists (Ervand Abrahamian); and as

- the beginning of the end of a 1000 years of quietism among Shi'i, a "real shift in Shiite political thought", "when Shiites began to see the possibility of freely experimenting with politics", (Khalid bin Sulieman Addadh).[63]

Ayatollah Sheikh Fazlollah Nouri who fought against a democratic law-making parliament in the 1905-1911 Iranian Constitutional Revolution (انقلاب مشروطه), predating Khomeini in supporting rule by sharia and opposing Western ideas in Iran.

Khomeini and Guardianship of the Islamic jurist as Islamic government

In the 1960s, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini was the leading cleric fighting the monarch (Shah) of the secularist Pahlavi dynasty. In early 1970, when he was exiled to the holy Shia city of Najaf, he gave a series of lectures on how "Islamic Government" required Wilayat Al Faqih. Leading up to the revolution, a book based on the lectures (The Jurist's Guardianship, Islamic Government) was spread widely among his network of followers in Iran.[64]

As a faqih, Khomeini was an expert on Islamic jurisprudence, and had originally supported an interpretation of Velayat-e faqih limited to "legal rulings, religious judgments, and intervention to protect the property of minors and the weak", even when "rulers are oppressive". In his 1941/1943 book Secrets Revealed;[65] he specifically stated "we do not say that government must be in the hands of the faqih".[66]

But in his 1970 book he argued that Faqih should get involved in politics not just in special situations, but that they must rule the state and society, and that monarchy or any other sort of non-Faqih government are "systems of unbelief ... all traces" of which it is the duty of Muslims to "destroy".[67] In a true Islamic state (he maintained) only those who have knowledge of Sharia should hold government posts, and the country's ruler should be the faqih (a guardian jurist, Vali-ye faqih), of the top rank—known as a Marjaʿ—who "surpasses all others in knowledge" of Islamic law and justice[68] — as well as having intelligence and administrative ability. Not only is the rule of Islamic jurists and obedience toward them an obligation of Islam, it is as important a religious obligation as any a Muslim has. "Our obeying holders of authority", like Islamic jurists, "is actually an expression of obedience to God."[69] Preserving Islam — for which Wilāyat al-Faqīh is necessary — "is more necessary even than prayer and fasting".[70]

The necessity of a Jurist leader to serve the people as "a vigilant trustee", enforcing "law and order", is not an ideal to strive for, but a matter of survival for Islam and Muslims. Without him, Islam will fall victim "to obsolescence and decay", as heretics, "atheists and unbelievers" add and subtract rites, institutions, and ordinances from the religion;[71] Muslim society will stay divided "into two groups: oppressors and oppressed";[72] Muslim government(s) will continue to be infested with corruption, "constant embezzlement";[73] not just lacking in competence and virtue, but actively serving as agents of imperialist Western powers.

"Foreign experts have studied our country and have discovered all our mineral reserves -- gold, copper, petroleum, and so on. They have also made an assessment of our people's intelligence and come to the conclusion that the only barrier blocking their way are Islam and the religious leadership."[74]

Their goal is

"to keep us backward, to keep us in our present miserable state so they can exploit our riches, our underground wealth, our lands and our human resources. They want us to remain afflicted and wretched, and our poor to be trapped in their misery ... they and their agents wish to go on living in huge palaces and enjoying lives of abominable luxury".[75]

Khomeini, Islamic Government, 1981: p.34</ref>

Guardianship of the Islamic jurist and the revolution

Though in exile, Khomeini, had an extensive network of capable loyalists operating in Iran. As the monarch of Iran lost popularity and revolutionary fervour spread, Khomeini became not only the undisputed leader of the Revolution that overthrew the Shah,[76][77] but one treated with great reverence, even awe.[note 12] However, while he often emphasized that Iran would become an 'Islamic state', he "never specified precisely what he meant by that term".[79] Those within his network may have been learning about the necessity of rule by Jurists, but "in his interview, speeches, messages and fatvas" to the public during this period, there is "not a single reference to velayat-e faqih."[79][80] When asked, Khomeini repeatedly denied Islamic clerics "want to rule" (August 18, 1979), "administer the state" (October 25, 1978), "hold power in the government" (26 October 1978), or that he himself would "occupy a post in the new government" (7 November 1978). [note 13] In fact, he could become indignant at the suggestion -- "those who pretend that religious dignitaries should not rule, poison the atmosphere and combat against Iran's interests" (August 18, 1979).[85] [note 14] As his supporters finalized a new post-revolutionary constitution and it became clear religious dignitaries (and specifically Khomeini) very much were going to rule, it came as shock to moderate and secular Muslims who had been within the fold of his broad movement, but by then he had solidified his hold on power.[80][3]

Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran

Following the overthrow of the Shah by the Iranian Revolution, a modified form of Khomeini's doctrine was incorporated into the Constitution of Islamic Republic of Iran,[87] adopted by referendum on 2 and 3 December 1979. It established the first country (and so far only) in history to apply the principal of velayat-e faqih to government. The jurist who surpassed all others in learning and justice as well as having intelligence and administrative ability, was Khomeini himself.

"The plan of the Islamic government" is "based upon wilayat al-faqih, as proposed by Imam Khumaynî ",[88] according to the constitution, which was drafted by an assembly made up primarily by disciples of Khomeini.[89]

While the constitution made concessions to popular sovereignty—including an elected president and parliament—"the Leader" was given "authority to dismiss the president, appoint the main military commanders, declare war and peace, and name senior clerics to the Guardian Council", (a powerful body which can veto legislation and disqualify candidates for office).[90][note 15]

Hezbollah of Lebanon

Khomeini's concept of wilayat al-faqih was to be universal and not to be limited to Iran. In one of his speeches, he declared:

We shall export our revolution to the whole world. Until the cry 'There is no god but Allah' resounds over the whole world, there will be struggle.[93][94][95][96]: 66

In the early 1980s, Ayatollah Khomeini sent some of his followers, including 1500 Iranian Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (pasdaran) instructors,[97] to Lebanon to form Hezbollah, a Shia Islamist political party and militant group, committed to bringing Islamic revolution[98] and rule of wilayat al-faqih in Lebanon.[99][100][101] A large fraction of Lebanon's population was Shia, and they had grown to become the largest confessional group in Lebanon, but had traditionally been subservient to Lebanese Christians and Sunni Muslims. Over time Hezbollah's para-military wing grew to be considered stronger than the Lebanese army,[102] and Hezbollah to become described as a "state within a state".[103] However, as of 2008, the goal of transforming Lebanon into "an Iranian-style" state" has been abandoned in favor of "a more inclusive approach".[104]

Under the Islamic Republic

The establishment of the Islamic Republic and Wilayat al-faqih rule was not without conflict. In his manifesto Islamic Government, Khomeini had warned sternly about measures that Islam will take with "troublesome" groups that damage "Islam and the Islamic state", and noted that the Prophet Muhammad had "eliminated" one "troublesome group" (i.e. the tribe Bani Qurayza whose men were all executed and women and children enslaved after the tribe collaborated with Muhammad's enemies and later refuse to convert to Islam).[105][note 16]

In revolutionary Iran, more than 7900 political prisoners were executed between 1981 and 1985, (according to historian Ervand Abrahamian, this compares with the "less than 100" killed by the monarchy during the eight years leading up to the revolution). In addition, the prison system was "drastically expanded" and prison conditions made "drastically worse" under the Islamic Republic.[107][108][109] Press freedom was also tightened, with the international group the Reporters Without Borders declaring Iran one of the world's most repressive countries for journalists" for the first 40 years after the revolution (1980-2020).[110]

In the world of Shi'i Islam, inside and outside of Iran, "the velayat-e faqih thesis was rejected by almost the entire dozen grand ayatollahs living" in the first years of the revolution.[111]

In 1988 and 89, shortly before and after Khomeini's death, significant changes were made to the constitution and the concept of Wilāyat al-Faqīh,[90] increasing the power of the Supreme Leader but reducing the scholarly qualifications needed for any new one.

In January–February 1988 Khomeini publicly propounded the theory of velayat-e motlaqaye faqih ("the absolute authority of the jurist"), whereby obedience to the ruling jurist is to "be as incumbent on the believer as the performance of prayer", and the guardian jurist's powers "extend even to the temporary suspension of such essential rites of Islam as the hajj",[6][112][note 17] (despite the fact that his 1970 book insists that "in Islam the legislative power and competence to establish laws belongs exclusively to God Almighty").[114] The new theory was instigated by the need "to break the stalemate" within the Islamic Government on "controversial items of social and economic legislation".[3][7]

In March 1989 Khomeini declared that all his successors as ruler should only be clerics knowledgeable about "the problems of the day" — the contemporary world and economic, social and political matters — not "religious" clerics,[115] despite the fact that he had spent decades preaching that only application of sharia law would solve the problems of this world.[115]

In the same month, Khomeini's officially designated successor, Hussein-Ali Montazeri, was ousted,[116] after he called for "an open assessment of failures" of the Revolution and an end to efforts to export it.[117] The Iranian constitution called for the Leader/Wali Al Faqih to be a marja', and Montazeri was the only marjaʿ al-taqlid beside Khomeini who had been part of Khomeini's movement, and the only senior cleric (formerly) trusted by Khomeini's network.[90] Consequently, after Khomeini died, the Assembly of Experts amended the constitution to remove scholarly seniority from the qualifications of the leader, accommodating the appointment of a "mid-ranking" but loyal cleric (Ali Khamenei), to be the new Faqih/Leader.[90] Lacking religious credentials, Khamenei has used "other means, such as patronage, media propaganda, and the security apparatus" to establish his power.[118]

In the 21st century, many have noted a severe loss of prestige in Iran for the fuqaha (Islamic jurists)[119] and for the concept of Wilayat al-faqih. "In the early 1980s, clerics were generally treated with elaborate courtesy." 20 years later, "clerics are sometimes insulted by school children and taxi drivers and they quite often put on normal clothes when venturing outside Qom."[120] Chants of ‘Death to the dictator’ (Marg Bar Diktator, dictator a reference to the Supreme Leader),[121] and “Death to velayat-e faqih”,[122] have been heard during protests in Iran, which have become serious enough to see as many as 1,500 protesters killed by security forces (in one series of protests in late 2019 and early 2020).[123][124][125] In Iraq, another Shia-majority country that is smaller and less stable than Iran and shares a border with it, sentiment against Iranian influence in 2019 led to demonstrations and attacks with Molotov cocktails against the Iranian Consulate in Karbala. Political forces alleged to be under the control of Iran there have sometimes been disparagingly referred to as "the arms of Wilayat al-Faqih."[126]

The current Supreme Leader, Ali Khamenei (age 84),[127] is thought to have taken some pain "to ensure that after his death Iran maintains an anti-American line and regime clerics continues to have "control of important state institutions". To this end, he has initiated a "massive purge" of "all but the most reliable and obedient members" of the political class, and worked to eliminate the government's generous consumer subsidies that while very popular drain the treasury.[128] According to Ray Takeyh of the Council on Foreign Relations, the choice of the next Supreme Leader will likely not be deliberated by the body designed to do that—the Assembly of Experts—but be made in a

behind-the-scenes selection process include the leadership of the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps, who wield both military and economic clout, and a number of conservative clerics, such as the current head of the assembly, Ahmad Khatami.[128]

Possible candidates to succeed Khamenei include current President Ebrahim Raisi and Khamenei's son, Mojtaba Khamenei.[128]

Velayat-e Faqih in the Iranian constitution

According to the constitution of Iran, Islamic republic is defined as a state ruled by Islamic jurists (Fuqaha). Article Five reads

"During the Occultation of the Walial-'Asr (may God hasten his reappearance), the wilayah and leadership of the Ummah devolve upon the just and pious faqih, who is fully aware of the circumstances of his age; courageous, resourceful, and possessed of administrative ability, will assume the responsibilities of this office in accordance with Article 107.[129]

(Other articles—107 to 112—specify the procedure for selecting the leader and list his constitutional functions.)

Articles 57 and 110 delineate the power of the ruling jurist. Article 57 states that there are other bodies/branches in the government but they are all under the control/supervision of the Leader.

The power of government in the Islamic Republic are vested in the legislature, the judiciary, and the executive powers, functioning under the supervision of the absolute religious leader and the leadership of the ummah.[33]

According to article 110, the supervisory powers of the Supreme Leader as a Vali-e-faqih are:

- appointing the jurists to the guardian council;

- appointing the highest judicial authority in the country;

- supreme command over the armed forces and Islamic Revolution Guards Corps;

- signing the certificate of appointment allowing the president to take office;

- dismissal of the president if he feels it is in the national interest;

- granting amnesty on the recommendation of the supreme court.[130]

The constitution quotes many verses of the Quran (21:92, 7:157, 21:105, 3:28, 28:5)[131] in support of its aims and goals. In support of "the continuation of the Revolution at home and abroad. ... other Islamic and popular movements to prepare the way for the formation of a single world community", and "to assure the continuation of the struggle for the liberation of all deprived and oppressed peoples in the world."[131] it quotes Q.21:92:

- "This your community is a single community, and I am your Lord, so worship Me".[131]

In support of "the righteous" assuming "the responsibility of governing and administering the country" it quotes Quranic verse Q.21:105:

- "Verily My righteous servants shall inherit the earth".[131]

On the basis of the principles of the trusteeship and the permanent Imamate, rule is counted as a function of jurists. Ruling jurists must hold the religious office of "source of imitation" [note 18] and be considered qualified to deliver independent judgments on religious general principles (fatwas). Furthermore, they must be upright, pious, committed experts on Islam, informed about the issues of the times, and known as God-fearing, brave and qualified for leadership.[132]

In chapter one of the constitution, where fundamental principles are expressed, article 2, section 6a, states that "continuous ijtihad of the fuqaha possessing necessary qualifications, exercised on the basis of the Qur'an and the Sunnah" is a principle in Islamic government.[133]

Varieties of viewpoints

There is a wide spectrum of viewpoints among Ja'fari (the Twelver Shia school of law) scholars about how much power wilāyat al-faqīh should have. At the minimal end, scholars

- restrict the scope of the doctrine to non-litigious matters (al-omour al-hesbiah),[2] people or things in Islamic society that lack a guardian over their interests (الامور الحسبیه), including unattended children, religious endowments (waqf),[9] and property for which no specific person is responsible, as well as judicial matters,[134] such as mediating disputes;

At the other extreme of the jurisprudence spectrum, is

- the "absolute authority of the jurist" (velayat-e motlaqaye faqih), over all public matters, where the mandate of the ruling jurisprudent/jurist/faqih is "among the primary ordinances of Islam".[135] Here the ruling faqih has control over all public matters including governance of states; has such power over religious affairs that he can (temporary) suspend religious obligations, such as the salat prayer or hajj;[6][3] and is owed such deference that the obligation of Muslims to obey him is as important as the obligation to perform those religious obligations he has the power to suspend.[7]

As of 2011, (at least according to authors Alireza Nader, David E. Thaler and S. R. Bohandy), those in Iran who believe in velayat-e faqih tend to fall into one of three categories listed below (the first and last roughly matching the two categories above, plus a middle view between the other two):

- those who believe faqih should not be involved in politics ("the "quietist" or "traditional concept") and question the need for a Supreme Leader — a view that while accepted in much of the Shi'i world, is outside the "red lines" of the Islamic Republic;[136]

- those (such as the late Ayatollah Hussein-Ali Montazeri) who believe that the leader exercising velayat-e-faqih should be a "religious-ideological guardian", not chief executive, and subject to democratic constraints such as direct elections, term limits, etc.;[137] and

- those (such as conservatives like Mohammad-Taqi Mesbah-Yazdi and vigilantes who attack reformers), who believe in "absolute" velayat-e faqih, and think those who do not are "betraying Khomeini and the Islamic Revolution".[138]

Limited role for Guardianship

Traditionally Shi'i jurists have tended to this interpretation, and for most Muslims wilayat al-faqih "meant no more than legal guardianship of senior clerics over those deemed incapable of looking after their own interests — minors, widows, and the insane"[139] (known as ‘mawla alayh’, one who is need of a guardian).[10] Political power was to be left to Shi'i monarchs called "Sultans", who should defend the territory against the non-Shi'a. For example, according to Iranian historian Ervand Abrahamian, in centuries of debate among Shi'i scholars, none have "ever explicitly contended that monarchies per se were illegitimate or that the senior clergy had the authority to control the state."[139] Other main responsibilities (i.e. guardianship) the 'ulama's were:

- to study the law based on the Qur'an, Sunnah and the teachings of the Twelve Imams.

- to use reason

- to update these laws;

- issue pronouncements on new problems;

- adjudicate in legal disputes; and

- distribute the khums contributions to worthy widows, orphans, seminary students, and indigent male descendants of the Prophet.[139]

Ahmed Vaezi (a supporter of the rule of the Islamic jurist) lists the "traditional roles and functions that qualified jurists undertake as deputies of the Imam", and that "in the history of Imami Shi’ism, marja’aiyya (authoritative reference) has largely been restricted to":[10]

- providing fatwas ("legal and juridical decrees") as a “Marja’a taqleed”, for those who "lack sufficient knowledge of Islamic law and the legal system (Shari’ah)" (which Vaezi insists is not part of guardianship/Wilayat al-Faqih);[10]

- mediating disputes and judging in legal cases. (which Vaezi insists Imami Twelver Shi'i Muslims believe is a "function of wilayat al-qada or al-hukuma);[10]

- Hisbiya Affairs (Al-Umur al-Hisbiya), i.e. providing a guardian for those who need one (for example, when the father of a minor or an insane person dies. Also religious endowments, inheritance and funerals). Imami jurists disagree (according to Vaezi) over whether this role is "appointed by the Shari’ah" or just a good idea because jurists are "naturally the best suited for the role".[10]

This view "dominated Shi’a discourse on issues of religion and governance for centuries before the Islamic Revolution", and still dominates it both in Najaf[140] and Karbala -- "Shi’a centers of thought" outside of the Islamic Republic of Iran[136]—and even within the IRI is still influential in the holy city of Qom.[136]

Supporters of keeping wilayat out of politics and governance argue universal wilayat puts sane adults in the same category as those who are impotent in their affairs, and need a guardian to protect their interests.[10]

This is not to say that sane, adult Shi'i do not seek and follow religious guidance from faqih. A long-standing doctrine in Shi'i Islam is that (Shi'i) Muslims should have a faqih "source to follow" or "religious reference", known as a Marjaʿ al-taqlid.[141] Marjaʿ receive tithes from their followers and issue fatwa to them, but unlike Wali al-Faqih, it is the individual Muslim who chooses the marjaʿ, and the marja' do not have the power of the state or of militias to enforce their commands.

A minority view was that senior faqih had the right to enter political disputes "but only temporarily and when the monarch endangered the whole community".[142] (An example being the December 1891 fatwa by Mirza Shirazi declaring tobacco forbidden, a successful effort to undermine the 1890 tobacco concession granted to the United Kingdom by Nasir al-Din Shah of Persia, giving British control over growth, sale and export of tobacco.)

Scriptural basisedit

The basis of wilayah/guardianship over mentally sound people (not just minors and mentally disabled) by God, the Prophet Muhammad, and the Imams, which appears in principles of faith and kalam can be interpreted from verse 5:55 in the Quran.

According to Ahmed Vaezi, "Imami Twelver Shi'i theologians refer to the Qur’an (especially Chapter 5, Verse 55) and prophetic traditions to support the exclusive authority (i.e. exclusive Wilayat) of the Imams".[10]

إِنَّمَا وَلِيُّكُمُ ٱللَّهُ وَرَسُولُهُۥ وَٱلَّذِينَ ءَامَنُوا۟ ٱلَّذِينَ يُقِيمُونَ ٱلصَّلَوٰةَ وَيُؤْتُونَ ٱلزَّكَوٰةَ وَهُمْ رَٰكِعُونَ

Your ally is none but Allah and therefore His Messenger and those who have believed - those who establish prayer and give zakah, and they bow in worship. (Q.5:55)[143][144]

In Q.5:55, "those who believe”, may sound like it refers to Muslim believers in general, but (according to Ahmed Vaezi) Shi’a commentators have interpreted "those who believe” to mean the Shi'i Imams.[10] (Sunni Muslims do not believe "those who believe" refers to the Imams.)

Role of ruler for Guardianedit

Khomeiniedit

Evolution of viewsedit

In an early work, Kashf al-Asrar, (Secrets Revealed, published in the 1940s), Khomeini had made ambiguous statements, arguing that “the state must be administered with the divine law, which defines the interests of the country and the people, and this cannot be achieved without clerical supervision (nezarat-e rouhanı)”,[145] but had not called for Jurists to rule or for them to replace monarchs -- "we do not say that government must be in the hands of the faqih".[146][66] He had also asserted that the practical "power of the mujtaheds" (i.e. faqih who have sufficient learning to conduct independent reasoning, known as Ijtihad),

excludes the government and includes only simple matters such as legal rulings, religious judgments, and intervention to protect the property of minors and the weak. Even when rulers are oppressive and against the people, they the mujtaheds will not try to destroy the rulers.[65]

Khomeini preached that God had created sharia to guide the Islamic community (ummah), the state to implement sharia, and faqih to understand and implement sharia.[147]

In dispensing with the traditional limited idea of wilayat al-faqih in his later work Islamic Government, Khomeini explains that there is little difference between guardianship over the nation and guardianship over a young person:

"Wilayat al-faqih is among the rational, extrinsic (ʿaqla' tibari) matters and has no reality apart from appointment (jaCI), like the appointment of a guardian for a young person. Guardianship over the nation and guardianship over a young person are no different from each other in regard to duty and position. It is like the Imam appointing someone to be the guardian of a young person, or appointing someone to govern, or appointing him to some post. In such instances, it is not reasonable to suggest that the Prophet and the Imam would differ from the faqih.[148][failed verification]

Shortly before he died, Khomeini gave perhaps his strongest statement about the power of the wilayat al-faqih in a letter to Ayatollah Ali Khamenei (later the second Supreme Leader of Iran:

The government or the absolute guardianship (al-wilayat al-mutlaqa) that is delegated to the noblest messenger of Allah is the most important divine law and has priority over all other ordinances of the divine law. If the powers of the government were restricted to the framework of ordinances of the law then the delegation of the authority to the Prophet would be a senseless phenomenon. I have to say that government is a branch of the Prophet's absolute Wilayat and one of the primary (first order) rules of Islam that has priority over all ordinances of the law even praying, fasting and Hajj…The Islamic State could prevent implementation of everything – devotional and non- devotional – that so long as it seems against Islam's interests.[149]

Scriptural basis for guardian being ruleredit

Khomeini's argumentsedit

While there are no sacred texts of Shia (or Sunni) Islam that include a straightforward statement that the Muslim community should or must be ruled over by Islamic jurists, Khomeini maintained there were "numerous traditions hadith that indicate the scholars of Islam are to exercise rule during the Occultation".[150] The first one he offered as proof was a saying addressed to a corrupt, but well-connected judge in early Islam, attributed to the first Imam, 'Ali --

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Velayat-e-faqihText je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk