A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Quran | |

|---|---|

| Arabic: ٱلْقُرْآن, romanized: al-Qurʾān | |

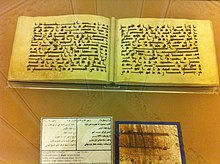

Two folios of the Birmingham Quran manuscript, an early manuscript written in Hijazi script likely dated within Muhammad's lifetime between c. 568–645 | |

| Information | |

| Religion | Islam |

| Language | Classical Arabic |

| Period | 610–632 CE |

| Chapters | 114 (list) See Surah |

| Verses | 6,348 (including the basmala) 6,236 (excluding the basmala) See Āyah |

| Full text | |

The Quran,[c] also romanized Qur'an or Koran,[d] is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (surah) which consist of individual verses (ayat). Besides its religious significance, it is widely regarded as the finest work in Arabic literature,[11][12][13] and has significantly influenced the Arabic language.

Muslims believe that the Quran was orally revealed by God to the final Islamic prophet Muhammad through the archangel Gabriel incrementally over a period of some 23 years, beginning on the Night of Power, when Muhammad was 40, and concluding in 632, the year of his death at age 61–62. Muslims regard the Quran as Muhammad's most important miracle, a proof of his prophethood, and the culmination of a series of divine messages starting with those revealed to the first Islamic prophet Adam, including the Islamic holy books of the Torah, Psalms, and Gospel.

The Quran is believed by Muslims to be not simply divinely inspired, but the literal words of God, and provides a complete code of conduct that offers guidance in every walk of their life. This divine character attributed to the Quran led Muslim theologians to fiercely debate whether the Quran was either "created or uncreated." According to tradition, several of Muhammad's companions served as scribes, recording the revelations. Shortly after the prophet's death, the Quran was compiled on the order of the first caliph Abu Bakr (r. 632–634) by the companions, who had written down or memorized parts of it. Caliph Uthman (r. 644–656) established a standard version, now known as the Uthmanic codex, which is generally considered the archetype of the Quran known today. There are, however, variant readings, with mostly minor differences in meaning. Controversy over the Quran's content integrity has rarely become an issue among Muslim history despite some hadiths stating that the textual integrity of the Quran was not preserved.

The Quran assumes the reader's familiarity with major narratives recounted in the Biblical and apocryphal scriptures. It summarizes some, dwells at length on others and, in some cases, presents alternative accounts and interpretations of events. The Quran describes itself as a book of guidance for humankind (2:185). It sometimes offers detailed accounts of specific historical events, and it often emphasizes the moral significance of an event over its narrative sequence. Supplementing the Quran with explanations for some cryptic Quranic narratives, and rulings that also provide the basis for Islamic law in most denominations of Islam, are hadiths—oral and written traditions believed to describe words and actions of Muhammad. During prayers, the Quran is recited only in Arabic. Someone who has memorized the entire Quran is called a hafiz. Ideally, verses are recited with a special kind of prosody reserved for this purpose, called tajwid. During the month of Ramadan, Muslims typically complete the recitation of the whole Quran during tarawih prayers. In order to extrapolate the meaning of a particular Quranic verse, Muslims rely on exegesis, or commentary rather than a direct translation of the text.

| Quran |

|---|

Etymology and meaning

The word qur'ān appears about 70 times in the Quran itself,[14] assuming various meanings. It is a verbal noun (maṣdar) of the Arabic verb qara'a (قرأ) meaning 'he read' or 'he recited'. The Syriac equivalent is qeryānā (ܩܪܝܢܐ), which refers to 'scripture reading' or 'lesson'.[15] While some Western scholars consider the word to be derived from the Syriac, the majority of Muslim authorities hold the origin of the word is qara'a itself.[16] Regardless, it had become an Arabic term by Muhammad's lifetime.[16] An important meaning of the word is the 'act of reciting', as reflected in an early Quranic passage: "It is for Us to collect it and to recite it (qur'ānahu)."[17]

In other verses, the word refers to 'an individual passage recited '. Its liturgical context is seen in a number of passages, for example: "So when al-qur'ān is recited, listen to it and keep silent."[18] The word may also assume the meaning of a codified scripture when mentioned with other scriptures such as the Torah and Gospel.[19]

The term also has closely related synonyms that are employed throughout the Quran. Each synonym possesses its own distinct meaning, but its use may converge with that of qur'ān in certain contexts. Such terms include kitāb ('book'), āyah ('sign'), and sūrah ('scripture'); the latter two terms also denote units of revelation. In the large majority of contexts, usually with a definite article (al-), the word is referred to as the waḥy ('revelation'), that which has been "sent down" (tanzīl) at intervals.[20][21] Other related words include: dhikr ('remembrance'), used to refer to the Quran in the sense of a reminder and warning; and ḥikmah ('wisdom'), sometimes referring to the revelation or part of it.[16][e]

The Quran describes itself as 'the discernment' (al-furqān), 'the mother book' (umm al-kitāb), 'the guide' (huda), 'the wisdom' (hikmah), 'the remembrance' (dhikr), and 'the revelation' (tanzīl; 'something sent down', signifying the descent of an object from a higher place to lower place).[22] Another term is al-kitāb ('The Book'), though it is also used in the Arabic language for other scriptures, such as the Torah and the Gospels. The term mus'haf ('written work') is often used to refer to particular Quranic manuscripts but is also used in the Quran to identify earlier revealed books.[16]

History

Prophetic era

Islamic tradition relates that Muhammad received his first revelation in 610 CE in the Cave of Hira on the Night of Power[23] during one of his isolated retreats to the mountains. Thereafter, he received revelations over a period of 23 years. According to hadith (traditions ascribed to Muhammad)[f][24] and Muslim history, after Muhammad immigrated to Medina and formed an independent Muslim community, he ordered many of his companions to recite the Quran and to learn and teach the laws, which were revealed daily. It is related that some of the Quraysh who were taken prisoners at the Battle of Badr regained their freedom after they had taught some of the Muslims the simple writing of the time. Thus a group of Muslims gradually became literate. As it was initially spoken, the Quran was recorded on tablets, bones, and the wide, flat ends of date palm fronds. Most suras were in use amongst early Muslims since they are mentioned in numerous sayings by both Sunni and Shia sources, relating Muhammad's use of the Quran as a call to Islam, the making of prayer and the manner of recitation. However, the Quran did not exist in book form at the time of Muhammad's death in 632 at age 61–62.[16][25][26][27][28][29] There is agreement among scholars that Muhammad himself did not write down the revelation.[30]

Sahih al-Bukhari narrates Muhammad describing the revelations as, "Sometimes it is (revealed) like the ringing of a bell" and A'isha reported, "I saw the Prophet being inspired Divinely on a very cold day and noticed the sweat dropping from his forehead (as the Inspiration was over)."[g] Muhammad's first revelation, according to the Quran, was accompanied with a vision. The agent of revelation is mentioned as the "one mighty in power,"[32] the one who "grew clear to view when he was on the uppermost horizon. Then he drew nigh and came down till he was (distant) two bows' length or even nearer."[28][33] The Islamic studies scholar Welch states in the Encyclopaedia of Islam that he believes the graphic descriptions of Muhammad's condition at these moments may be regarded as genuine, because he was severely disturbed after these revelations. According to Welch, these seizures would have been seen by those around him as convincing evidence for the superhuman origin of Muhammad's inspirations. However, Muhammad's critics accused him of being a possessed man, a soothsayer or a magician since his experiences were similar to those claimed by such figures well known in ancient Arabia. Welch additionally states that it remains uncertain whether these experiences occurred before or after Muhammad's initial claim of prophethood.[34]

The Quran describes Muhammad as "ummi",[35] which is traditionally interpreted as 'illiterate', but the meaning is rather more complex. Medieval commentators such as al-Tabari (d. 923) maintained that the term induced two meanings: first, the inability to read or write in general; second, the inexperience or ignorance of the previous books or scriptures (but they gave priority to the first meaning). Muhammad's illiteracy was taken as a sign of the genuineness of his prophethood. For example, according to Fakhr al-Din al-Razi, if Muhammad had mastered writing and reading he possibly would have been suspected of having studied the books of the ancestors. Some scholars such as W. Montgomery Watt prefer the second meaning of ummi—they take it to indicate unfamiliarity with earlier sacred texts.[28][36]

The final verse of the Quran was revealed on the 18th of the Islamic month of Dhu al-Hijja in the year 10 A.H., a date that roughly corresponds to February or March 632. The verse was revealed after the Prophet finished delivering his sermon at Ghadir Khumm.

Compilation and preservation

Following Muhammad's death in 632, a number of his companions who memorized the Quran were killed in the Battle of al-Yamama by Musaylima. The first caliph, Abu Bakr (r. 632–634), subsequently decided to collect the book in one volume so that it could be preserved.[37] Zayd ibn Thabit (d. 655) was the person to collect the Quran since "he used to write the Divine Inspiration for Allah's Apostle".[38] Thus, a group of scribes, most importantly Zayd, collected the verses and produced a hand-written manuscript of the complete book. The manuscript according to Zayd remained with Abu Bakr until he died. Zayd's reaction to the task and the difficulties in collecting the Quranic material from parchments, palm-leaf stalks, thin stones (collectively known as suhuf, any written work containing divine teachings)[39] and from men who knew it by heart is recorded in earlier narratives. In 644, Muhammad's widow Hafsa bint Umar was entrusted with the manuscript until the third caliph, Uthman (r. 644–656),[38] requested the standard copy from her.[40] (According to historian Michael Cook, early Muslim narratives about the collection and compilation of the Quran sometimes contradict themselves. "Most ... make Uthman little more than an editor, but there are some in which he appears very much a collector, appealing to people to bring him any bit of the Quran they happen to possess." Some accounts also "suggest that in fact the material" Abu Bakr worked with "had already been assembled", which since he was the first caliph, would mean they were collected when Muhammad was still alive.)[41]

In about 650, Uthman began noticing slight differences in pronunciation of the Quran as Islam expanded beyond the Arabian Peninsula into Persia, the Levant, and North Africa. In order to preserve the sanctity of the text, he ordered a committee headed by Zayd to use Abu Bakr's copy and prepare a standard text of the Quran.[42][43] Thus, within 20 years of Muhammad's death (around 650 CE),[44] the complete Quran was committed to written form, a codex. That text became the model from which copies were made and promulgated throughout the urban centers of the Muslim world, and other versions are believed to have been destroyed.[42][45][46][47] The present form of the Quran text is accepted by Muslim scholars to be the original version compiled by Abu Bakr.[28][29][h][i]

This preservation of the Quran is considered one of the miracles of the Quran among the Islamic faithful.[j]

The Shia recite the Qur'an according to the qira'at of Hafs on authority of ‘Asim, which is the prevalent Qira’at in the Islamic world[53] and believe that the Quran was gathered and compiled by Muhammad during his lifetime.[54][55] It is claimed that the Shia had more than 1,000 hadiths ascribed to the Shia Imams which indicate the distortion of the Quran[56] and according to Etan Kohlberg, this belief about Quran was common among Shiites in the early centuries of Islam.[57] In his view, Ibn Babawayh was the first major Twelver author "to adopt a position identical to that of the Sunnis" and the change was a result of the "rise to power of the Sunni 'Abbasid caliphate," whence belief in the corruption of the Quran became untenable vis-a-vis the position of Sunni “orthodoxy”.[58] Alleged distortions to have been carried out to remove any references to the rights of Ali, the Imams and their supporters and the disapproval of enemies, such as Umayyads and Abbasids.[59]

Other personal copies of the Quran might have existed including Ibn Mas'ud's and Ubay ibn Ka'b's codex, none of which exist today.[16][42][60]

Academic research

The Quran assumes the reader's familiarity with major narratives recounted in the Biblical and apocryphal scriptures. It summarizes some, dwells at length on others and, in some cases, presents alternative accounts and interpretations of events.[61][62] The Quran describes itself as a book of guidance for humankind (2:185). It sometimes offers detailed accounts of specific historical events, and it often emphasizes the moral significance of an event over its narrative sequence.[63] Supplementing the Quran with explanations for some cryptic Quranic narratives, and rulings that also provide the basis for Islamic law in most denominations of Islam,[24][k]

Since Muslims could regard criticism of the Qur'an as a crime of apostasy punishable by death under sharia, it seemed impossible to conduct studies on the Qur'an that went beyond textual criticism.[64][65] Until the early 1970s,[66] non-Muslim scholars of Islam —while not accepting traditional explanations for divine intervention— accepted the above-mentioned traditional origin story in most details.[37]

Rasm: "ٮسم الله الرحمں الرحىم"

University of Chicago professor Fred Donner states that:[67]

here was a very early attempt to establish a uniform consonantal text of the Qurʾān from what was probably a wider and more varied group of related texts in early transmission.… After the creation of this standardized canonical text, earlier authoritative texts were suppressed, and all extant manuscripts—despite their numerous variants—seem to date to a time after this standard consonantal text was established.

Although most variant readings of the text of the Quran have ceased to be transmitted, some still are.[68][69] There has been no critical text produced on which a scholarly reconstruction of the Quranic text could be based.[l]

In 1972, in a mosque in the city of Sana'a, Yemen, manuscripts "consisting of 12,000 pieces" were discovered that were later proven to be the oldest Quranic text known to exist at the time. The Sana'a manuscripts contain palimpsests, manuscript pages from which the text has been washed off to make the parchment reusable again—a practice which was common in ancient times due to the scarcity of writing material. However, the faint washed-off underlying text (scriptio inferior) is still barely visible.[71] Studies using radiocarbon dating indicate that the parchments are dated to the period before 671 CE with a 99 percent probability.[72][73] The German scholar Gerd R. Puin has been investigating these Quran fragments for years. His research team made 35,000 microfilm photographs of the manuscripts, which he dated to the early part of the 8th century. Puin has noted unconventional verse orderings, minor textual variations, and rare styles of orthography, and suggested that some of the parchments were palimpsests which had been reused. Puin believed that this implied an evolving text as opposed to a fixed one.[74]

In 2015, a single folio of a very early Quran, dating back to 1370 years earlier, was discovered in the library of the University of Birmingham, England. According to the tests carried out by the Oxford University Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit, "with a probability of more than 95%, the parchment was from between 568 and 645". The manuscript is written in Hijazi script, an early form of written Arabic.[75] This possibly was one of the earliest extant exemplars of the Quran, but as the tests allow a range of possible dates, it cannot be said with certainty which of the existing versions is the oldest.[75] Saudi scholar Saud al-Sarhan has expressed doubt over the age of the fragments as they contain dots and chapter separators that are believed to have originated later.[76] The Birmingham manuscript holds significance amongst scholarship because of its early dating and potential overlap with the dominant tradition over the lifetime of Muhammad c. 570 to 632 CE[77] and used as evidence to support conventional wisdom and to refute the revisionists' views on the history of the writing of the Quran.[78]

Significance in Islam

| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

|

Muslims believe the Quran to be God's literal words,[16] a complete code of life,[79] the final revelation to humanity, a work of divine guidance revealed to Muhammad through the angel Gabriel.[25][80][81][82] Quran says, "With the truth we (God) have sent it down and with the truth it has come down"[83] and frequently asserts in its text that it is divinely ordained.[84] The Quran speaks of a written pre-text that records God's speech before it is sent down, the "preserved tablet" that is the basis of the belief in fate also, and Muslims believe that the Quran was sent down or started to be sent down on the Laylat al-Qadr. [85][86] Due to the belief in revelation and divine writing, the word used by Islamic literature to express the context of the Qur'anic verses is "Asbab al-Nuzul".

Revered by pious Muslims as "the holy of holies",[87] whose sound moves some to "tears and ecstasy",[88] it is the physical symbol of the faith, the text often used as a charm on occasions of birth, death, marriage. Traditionally, before starting to read the Quran, ablution is performed, one seeks refuge in Allah from the accursed satan, and the reading begins by mentioning the names of Allah, Rahman and Rahim together known as basmala. Consequently,

It must never rest beneath other books, but always on top of them, one must never drink or smoke when it is being read aloud, and it must be listened to in silence. It is a talisman against disease and disaster.[87][89]

The Quran was the word of God (Kalām Allāh) (again, a word used for Jesus in the Quran (An-Nisa: 171), and its nature and whether it was created became a matter of fierce debate among religious scholars;[90][91] and with the involvement of the political authority in the discussions, some Muslim religious scholars who stood against the political stance faced religious persecution during the caliph al-Ma'mun period and the following years.

Muslims believe that the present Quranic text corresponds to that revealed to Muhammad, and according to their interpretation of Quran 15:9, it is protected from corruption ("Indeed, it is We who sent down the Quran and indeed, We will be its guardians").[92] Muslims consider the Quran to be a sign of the prophethood of Muhammad and the truth of the religion. For this reason, in traditional Islamic societies, great importance was given to children memorizing the Quran, and those who memorized the entire Quran were honored with the title of hafiz. Even today, millions of Muslims frequently refer to the Quran to justify their actions and desires",[m] and see it as the source of scientific knowledge,[94] though some refer to it as weird or pseudoscience.[95]

Inimitability

In Islam, ’i‘jāz (Arabic: اَلْإِعْجَازُ), "inimitability challenge" of the Qur'an in sense of feṣāḥa and belagha (both eloquence and rhetoric) is the doctrine which holds that the Qur’ān has a miraculous quality, both in content and in form, that no human speech can match.[96] According to this, the Qur'an is a miracle and its inimitability is the proof granted to Muhammad in authentication of his prophetic status.[97] The literary quality of the Qur'an has been praised by Muslim scholars and by many non-Muslim scholars.[98] The doctrine of the miraculousness of the Quran is further emphasized by Muhammad's illiteracy since the unlettered prophet could not have been suspected of composing the Quran.[99]

The Quran is widely regarded as the finest work in Arabic literature.[100][101][102] The emergence of the Qur’ān was an oral and aural poetic[103] experience; the aesthetic experience of reciting and hearing the Qur’ān is often regarded as one of the main reasons behind conversion to Islam in the early days.[104] In pre-Islamic Arabs, poetry was an element of challenge, propaganda and warfare,[105] and those who incapacitated their opponents from doing the same in feṣāḥa and belagha socially honored, as could be seen on Mu'allaqat poets. The etymology of the word “shā'ir; (poet)” connotes the meaning of a man of inspirational knowledge, of unseen powers. `To the early Arabs poetry was ṣihr ḥalāl and the poet was a genius who had supernatural communications with the jinn or spirits, the muses who inspired him.’[104] Although pre-Islamic Arabs gave poets status associated with suprahuman beings, soothsayers and prophecies were seen as persons of lower status. Contrary to later hurufic and recent scientific prophecy claims, traditional miracle statements about the Quran hadn't focused on prophecies, with a few exceptions like the Byzantine victory over the Persians[106] in wars that continued for hundreds of years with mutual victories and defeats.

The first works about the ’i‘jāz of the Quran began to appear in the 9th century in the Mu'tazila circles, which emphasized only its literary aspect, and were adopted by other religious groups.[107] According to grammarian Ar-Rummani the eloquence contained in the Quran consisted of tashbīh, istiʿāra, taǧānus, mubālaġa, concision, clarity of speech (bayān), and talāʾum. He also added other features developed by himself; the free variation of themes (taṣrīf al-maʿānī), the implication content (taḍmīn) of the expressions and the rhyming closures (fawāṣil).[108] The most famous works on the doctrine of inimitability are two medieval books by the grammarian Al Jurjani (d. 1078 CE), Dala’il al-i'jaz ('the Arguments of Inimitability') and Asraral-balagha ('the Secrets of Eloquence').[109] Al Jurjani believed that Qur'an's eloquence must be a certain special quality in the manner of its stylistic arrangement and composition or a certain special way of joining words.[99] Angelika Neuwirth lists the factors that led to the emergence of the doctrine of ’i‘jāz: The necessity of explaining some challenging verses in the Quran;[110] In the context of the emergence of the theory of "proofs of prophecy" (dâ'il an-nubuwwa) in Islamic theology, proving that the Quran is a work worthy of the emphasized superior place of Muhammad in the history of the prophets, thus gaining polemical superiority over Jews and Christians; Preservation of Arab national pride in the face of confrontation with the Iranian Shu'ubiyya movement, etc.[111]

In a different line; The miracle claim that the Quran was encrypted using the number 19 was put forward by Rashad Khalifa; The claim attracted criticism because it included claims against the integrity of the text, which is mostly accepted by Muslims,[112][n] and the Khalifa was killed by his own student in an assassination[113] possibly organized by a Sunni radical group.[114]

In worship

Surah Al-Fatiha, the first chapter of the Quran, is recited in full in every rakat of salah and on other occasions. This surah, which consists of seven verses, is the most often recited surah of the Quran:[16]

بِسْمِ ٱللَّهِ ٱلرَّحْمَٰنِ ٱلرَّحِيمِ |

In the Name of Allah the Entirely Merciful, the Especially Merciful. |

| —Quran 1:1-7 | —Sahih International English translation |

Other sections of the Quran of choice are also read in daily prayers. Surah Al-Ikhlāṣ is second in frequency of Qur'an recitation, for according to many early authorities, Muhammad said that Ikhlāṣ is equivalent to one-third of the whole Quran.[115]

قُلۡ هُوَ ٱللَّهُ أَحَدٌ |

Say, ˹O Prophet,˺ “He is God—One ˹and Indivisible˺; |

| —Surah Al-Ikhlāṣ 112:1-4 | —The Clear Quran English translation |

Respect for the written text of the Quran is an important element of religious faith by many Muslims, and the Quran is treated with reverence. Based on tradition and a literal interpretation of Quran 56:79 ("none shall touch but those who are clean"), some Muslims believe that they must perform a ritual cleansing with water (wudu or ghusl) before touching a copy of the Quran, although this view is not universal.[16] Worn-out copies of the Quran are wrapped in a cloth and stored indefinitely in a safe place, buried in a mosque or a Muslim cemetery, or burned and the ashes buried or scattered over water.[116] While praying, the Quran is only recited in Arabic.[117]

In Islam, most intellectual disciplines, including Islamic theology, philosophy, mysticism and jurisprudence, have been concerned with the Quran or have their foundation in its teachings.[16] Muslims believe that the preaching or reading of the Quran is rewarded with divine rewards variously called ajr, thawab, or hasanat.[118]

In Islamic art

The Quran also inspired Islamic arts and specifically the so-called Quranic arts of calligraphy and illumination.[16] The Quran is never decorated with figurative images, but many Qurans have been highly decorated with decorative patterns in the margins of the page, or between the lines or at the start of suras. Islamic verses appear in many other media, on buildings and on objects of all sizes, such as mosque lamps, metal work, pottery and single pages of calligraphy for muraqqas or albums.

-

Calligraphy, 18th century, Brooklyn Museum

-

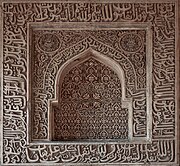

Quranic inscriptions, Bara Gumbad mosque, Delhi, India

-

Quran page decoration art, Ottoman period

-

Quranic verses, Shahizinda mausoleum, Samarkand, Uzbekistan

-

The leaves from Quran written in gold and contoured with brown ink with a horizontal format suited to classical Kufic calligraphy, which became common under the early Abbasid caliphs.

Contents

The Quranic content is concerned with basic Islamic beliefs including the existence of God and the resurrection. Narratives of the early prophets, ethical and legal subjects, historical events of Muhammad's time, charity and prayer also appear in the Quran. The Quranic verses contain general exhortations regarding right and wrong and historical events are related to outline general moral lessons. Verses pertaining to natural phenomena have been interpreted by Muslims as an indication of the authenticity of the Quranic message.[119] The style of the Quran has been called "allusive", with commentaries needed to explain what is being referred to—"events are referred to, but not narrated; disagreements are debated without being explained; people and places are mentioned, but rarely named."[120]

Persian miniature (c. 1595), tinted drawing on paper

Many places, subjects and mythological figures in the culture of Arabs and many nations in their historical neighbourhoods, especially Judeo-Christian stories,[121] are included in the Quran with small allusions, references or sometimes small narratives such as firdaws, Seven sleepers, Queen of Sheba etc. However, some philosophers and scholars such as Mohammed Arkoun, who emphasize the mythological character of the language and content of the Quran, are met with rejectionist attitudes in Islamic circles.[122]

The stories of Yusuf and Zulaikha, Moses, Family of Amram (parents of Mary according to Quran) and mysterious hero[123][124][125][126] Dhul-Qarnayn ("the man with two horns") who built a barrier against Gog and Magog that will remain until the end of time are more detailed and longer stories. Apart from semi-historical events and characters such as King Solomon and David, about Jewish history as well as the exodus of the Israelites from Egypt, tales of the hebrew prophets accepted in Islam, such as Creation, the Flood, struggle of Abraham with Nimrod, sacrifice of his son occupy a wide place in the Quran.

Monotheism

The Quran uses cosmological and contingency arguments in various verses without referring to the terms to prove the existence of God. Therefore, the universe is originated and needs an originator, and whatever exists must have a sufficient cause for its existence. Besides, the design of the universe is frequently referred to as a point of contemplation: "It is He who has created seven heavens in harmony. You cannot see any fault in God's creation; then look again: Can you see any flaw?"[127][128]

The central theme of the Quran is monotheism. God is depicted as living, eternal, omniscient and omnipotent (see, e.g., Quran 2:20, 2:29, 2:255). God's omnipotence appears above all in his power to create. He is the creator of everything, of the heavens and the earth and what is between them (see, e.g., Quran 13:16, 2:253, 50:38, etc.). All human beings are equal in their utter dependence upon God, and their well-being depends upon their acknowledging that fact and living accordingly.[28][119]

Even though Muslims do not doubt about the existence and unity of God, they may have adopted different attitudes that have changed and developed throughout history regarding his nature (attributes), names and relationship with creation.

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Quran

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk