A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

This article needs to be updated. (October 2022) |

Software for COVID-19 pandemic mitigation takes many forms. It includes mobile apps for contact tracing and notifications about infection risks, vaccine passports, software for enabling – or improving the effectiveness of – lockdowns and social distancing, Web software for the creation of related information services, and research and development software. A common issue is that few apps interoperate, reducing their effectiveness.

Contact tracing

COVID-19 apps include mobile-software applications for digital contact-tracing—i.e. the process of identifying persons ("contacts") who may have been in contact with an infected individual—deployed during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Numerous tracing applications have been developed or proposed, with official government support in some territories and jurisdictions. Several frameworks for building contact-tracing apps have been developed. Privacy concerns have been raised, especially about systems that are based on tracking the geographical location of app users.

Less overtly intrusive alternatives include the co-option of Bluetooth signals to log a user's proximity to other cellphones. (Bluetooth technology has form in tracking cell-phones' locations.)) On 10 April 2020, Google and Apple jointly announced that they would integrate functionality to support such Bluetooth-based apps directly into their Android and iOS operating systems. India's COVID-19 tracking app Aarogya Setu became the world's fastest growing application—beating Pokémon Go—with 50 million users in the first 13 days of its release. (Full article...)

Design

Design decisions relate to issues such as privacy, data-storage and security. Apps are generally not interoperable.[1][2]

Use

Voluntary use by the public was ineffective.[3][4][5] A lack of features and bugs further reduced usefulness.[6]

Some apps include "check-ins" that enable exposure notifications when entering public venues such as fitness centres.[7] One such example is the We-Care project that used anonymity and crowdsourced information about which check-ins are essential, to alert exposed users.[8][9][10]

Digital vaccination certificates

Digital vaccine passports and vaccination certificates use software for verifying vaccination status.[4]

Such certificates were used to regulate access to events, buildings and services such as airplanes, concert venues and health clubs[4] and travel across borders.[11]

Hurdles

Given the uneven distribution of vaccines across jurisdictions, granting privileges based on vaccination status certification means that those with easier vaccine access have unfair access to those privileges.[12] If vaccination status is only verifiable using digital technology, those without that technology may also lose access even if they are vaccinated. Such privileging mechanisms may exacerbate inequality,[13] increase risks of deliberate infections or transmission,[11][14] Public health justifications for restricting behavior based on vaccine status have become less frequent over the course of the pandemic as vaccines do not stop transmission.

Design

Some teams are developing interoperable solutions, but this is not common.[4][15] Governments express concerns over data sovereignty.[16]

WHO established a "working group focused on establishing standards for a common architecture for a digital smart vaccination certificate to support vaccine(s) against COVID-19 and other immunizations".[13][17]

The COVID-19 Credentials Initiative hosted by Linux Foundation Public Health (LFPH) is a global initiative working to develop and deploy privacy-preserving, tamper-evident and verifiable credential certification projects based on the open standard Verifiable Credentials (VCs).[18][19][14]

Laurin Weissinger argued that it is important for such software to be fully free and open source, to clarify concepts and designs, to have it tested by security experts and to describe data that is collected and how it is used to build trust.[20] Jenny Wanger contended that it is essential for such software to be open source.[21] Jay Stanley affirmed this notion and warned that an "architecture that is not good for transparency, privacy, or user control" could set a "bad standard" for future credentialing systems.[22]

Websites

Web dashboards[23][24] are widely used for tracking the status of the pandemic.[citation needed]

The Wikimedia project Scholia provides a graphical interface around data in Wikidata – such as literature about a specific coronavirus protein – to help with research, research-analysis, data interoperability, applications, updates, and data-mining.[25][26]

A group of online archivists used open access PHP- and Linux-based shadow library Sci-Hub to create an archive of over 5000 articles about coronaviruses. Making the archive openly accessible is currently illegal.[27] Sci-Hub provides free full access for most scientific pandemic publications.[citation needed]

Multiple scientific publishers created open access portals, including the Cambridge University Press,[28] the Europe branch of the Scholarly Publishing and Academic Resources Coalition,[29] The Lancet,[30] John Wiley and Sons,[31] and Springer Nature.[32]

Physician and open access advocate Josh Farkas has added a chapter on COVID-19 treatment to his e-book on intensive care medicine, hosted by EMCrit.[33]

Medical software

This section needs expansion with: Content regarding apps for citizen science from its respective article, and the article on the pandemic's impacts on STEM, particularly bulleted lists. You can help by adding to it. (September 2021) |

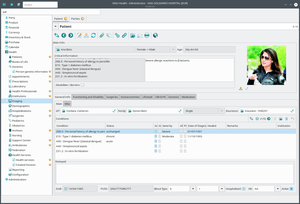

GNU Health

The open source, Qt-[34][35] and GTK-based GNU Health offer a variety of default features for use during pandemics.[24] It allows parties to pool efforts on a single, integrated program – instead of individual, programs for specific purposes. Existing features include a way for making clinical information available and update it in any health institution via a globally unique "Person Universal ID". It includes lab test templates and functionalities, digital signing and encryption.[36]

Vaccination management

Software helps manage vaccine distribution, including verifying the cold chain, and to record vaccination events.[37]

Screening

In China, Web-technologies were used to direct individuals to appropriate resources. Infrared thermal cameras are used to detect individuals with fever.[38] Machine learning has been used for diagnosis and risk prediction.[38]

Quarantining

Electronic monitoring has been used to manage quarantine adherence.Furthermore, various software designs may threaten civil liberties and infringe on privacy.[38] China informs individuals about whether and how long they must quarantine via a phone app and informs authorities about their compliance.[39]

Genomic data

Nextstrain is an open source platform for pathogen genomic data such as about viral evolution and was used for research about novel variants.

Vaccine production

Software has been used in leaks and industrial espionage of vaccine-related data.[40] Machine learning has been applied to improve vaccine manufacturing productivity.[41]

Modelling

Software models and simulations for SARS-CoV-2, including spread,[42] functional mechanisms and properties,[43][44][42] efficacy of potential treatments,[44][42] transmission risks, vaccination modelling/monitoring, (computational fluid dynamics, computational epidemiology, computational biology/computational systems biology were developed by governments, universities, and companies.

Modelling software and related software is also used to evaluate impacts on the environment and the economy.

Distributed computing

The volunteer distributed computing project Folding@home simulates protein folding. It was used for medical research. In March 2020 it became the world's first system to reach one exaFLOPS[45][46][47] and reached approximately 2.43 x86 exaFLOPS by 13 April 2020 – many times faster than Summit, the fastest supercomputer of that time.[48]

That month Rosetta@home joined the effort. Researchers announced that Rosetta@home allowed them to "accurately predict the atomic-scale structure of an important coronavirus protein weeks before it could be measured in the lab."[49]

In May 2020, the OpenPandemics—COVID-19 partnership was launched between Scripps Research and IBM's World Community Grid. The partnership is a distributed computing project that "will automatically run a simulated experiment in the background that will help predict the efficacy of a particular chemical compound as a potential treatment for COVID-19."[50]

Drug repurposing research and drug development

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2021) |

Supercomputers – including Summit and Fugaku – have been used to explore potential treatments by running simulations with data on already-approved medications.[51][52][53][42][44] Two early examples of supercomputer consortia are:

- The United States Department of Energy, National Science Foundation, NASA, industry, and nine universities pooled resources to access supercomputers from IBM, combined with cloud computing resources from Hewlett Packard Enterprise, Amazon, Microsoft, and Google, for drug discovery.[54][55] The COVID-19 High Performance Computing Consortium attempted to forecast disease spread, model vaccines, and screen thousands of chemical compounds.[54][55] The Consortium had used 437 petaFLOPS of computing power by May 2020.[56]

- The C3.ai Digital Transformation Institute, an additional consortium of Microsoft, six universities (including MIT), and the National Center for Supercomputer Applications in Illinois, working under the auspices of artificial intelligence software company C3.ai pooled supercomputer resources toward drug discovery, medical protocol development and public health strategy improvement, as well as awarding grants for similar purposes.[57][58]

See also

- Timeline of computing 2020–present

- Pandemic prevention § Surveillance and mapping

- COVID-19 surveillance

- Teamwork

- Information management

- Open-source ventilator

- Bioinformatics

- Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on science and technology#Computing and machine learning research and citizen science

- Public health mitigation of COVID-19 § Information technology

- Technology policy