A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Old Church Slavonic | |

|---|---|

| Old Church Slavic | |

| Ⱌⱃⱐⰽⱏⰲⱐⱀⱁⱄⰾⱁⰲⱑⱀⱐⱄⰽⱏ ⱗⰸⱏⰺⰽⱏ Црькъвьнословѣ́ньскъ ѩꙁꙑ́къ | |

| |

| Native to | Formerly in Slavic areas under the influence of Byzantium (both Catholic and Orthodox) |

| Region | |

| Era | 9th–11th centuries; then evolved into several variants of Church Slavonic including Middle Bulgarian |

Indo-European

| |

| Glagolitic, Cyrillic | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | cu |

| ISO 639-2 | chu |

| ISO 639-3 | chu (includes Church Slavonic) |

| Glottolog | chur1257 Church Slavic |

| Linguasphere | 53-AAA-a |

Old Church Slavonic[1] or Old Slavonic (/sləˈvɒnɪk, slæˈvɒn-/ slə-VON-ik, slav-ON-)[a] is the first Slavic literary language.

Historians credit the 9th-century Byzantine missionaries Saints Cyril and Methodius with standardizing the language and undertaking the task of translating the Gospels and necessary liturgical books into it[9] as part of the Christianization of the Slavs.[10][11] It is thought to have been based primarily on the dialect of the 9th-century Byzantine Slavs living in the Province of Thessalonica (in present-day Greece).

Old Church Slavonic played an important role in the history of the Slavic languages and served as a basis and model for later Church Slavonic traditions, and some Eastern Orthodox and Eastern Catholic churches use this later Church Slavonic as a liturgical language to this day.

As the oldest attested Slavic language, OCS provides important evidence for the features of Proto-Slavic, the reconstructed common ancestor of all Slavic languages.

Nomenclature

The name of the language in Old Church Slavonic texts was simply Slavic (словѣ́ньскъ ѩꙁꙑ́къ, slověnĭskŭ językŭ),[12] derived from the word for Slavs (словѣ́нє, slověne), the self-designation of the compilers of the texts. This name is preserved in the modern native names of the Slovak and Slovene languages. The language is sometimes called Old Slavic, which may be confused with the distinct Proto-Slavic language. Different strains of nationalists have tried to 'claim' Old Church Slavonic; thus OCS has also been variously called Old Bulgarian, Old Croatian, Old Macedonian or Old Serbian, or even Old Slovak, Old Slovenian.[13] The commonly accepted terms in modern English-language Slavic studies are Old Church Slavonic and Old Church Slavic.

The term Old Bulgarian[14] (Bulgarian: старобългарски, German: Altbulgarisch) is the designation used by most Bulgarian-language writers. It was used in numerous 19th-century sources, e.g. by August Schleicher, Martin Hattala, Leopold Geitler and August Leskien,[15][16][17] who noted similarities between the first literary Slavic works and the modern Bulgarian language. For similar reasons, Russian linguist Aleksandr Vostokov used the term Slav-Bulgarian. The term is still used by some writers but nowadays normally avoided in favor of Old Church Slavonic.

The term Old Macedonian[18][19][20][21][22][23][24] is occasionally used by Western scholars in a regional context.

The obsolete[25] term Old Slovenian[25][26][27][28] was used by early 19th-century scholars who conjectured that the language was based on the dialect of Pannonia.

History

It is generally held that the language was standardized by two Byzantine missionaries, Cyril and his brother Methodius, for a mission to Great Moravia (the territory of today's eastern Czech Republic and western Slovakia; for details, see Glagolitic alphabet).[29] The mission took place in response to a request by Great Moravia's ruler, Duke Rastislav for the development of Slavonic liturgy.[30]

As part of preparations for the mission, in 862/863, the missionaries developed the Glagolitic alphabet and translated the most important prayers and liturgical books, including the Aprakos Evangeliar, the Psalter, and the Acts of the Apostles, allegedly basing the language on the Slavic dialect spoken in the hinterland of their hometown, Thessaloniki,[b] in present-day Greece.

Based on a number of archaicisms preserved until the early 20th century (the articulation of yat as /æ/ in Boboshticë, Drenovë, around Thessaloniki, Razlog, the Rhodopes and Thrace and of yery as /ɨ/ around Castoria and the Rhodopes, the presence of decomposed nasalisms around Castoria and Thessaloniki, etc.), the dialect is posited to have been part of a macrodialect extending from the Adriatic to the Black sea, and covering southern Albania, northern Greece and the southernmost parts of Bulgaria.[32]

Because of the very short time between Rastislav's request and the actual mission, it has been widely suggested that both the Glagolitic alphabet and the translations had been "in the works" for some time, probably for a planned mission to the Bulgaria.[33][34][35]

The language and the Glagolitic alphabet, as taught at the Great Moravian Academy (Slovak: Veľkomoravské učilište), were used for government and religious documents and books in Great Moravia between 863 and 885. The texts written during this phase contain characteristics of the West Slavic vernaculars in Great Moravia.

In 885 Pope Stephen V prohibited the use of Old Church Slavonic in Great Moravia in favour of Latin.[36] King Svatopluk I of Great Moravia expelled the Byzantine missionary contingent in 886.

Exiled students of the two apostles then brought the Glagolitic alphabet to the Bulgarian Empire, being at least some of them Bulgarians themselves.[37][38][39] Boris I of Bulgaria (r. 852–889) received and officially accepted them; he established the Preslav Literary School and the Ohrid Literary School.[40][41][42] Both schools originally used the Glagolitic alphabet, though the Cyrillic script developed early on at the Preslav Literary School, where it superseded Glagolitic as official in Bulgaria in 893.[43][44][45][46]

The texts written during this era exhibit certain linguistic features of the vernaculars of the First Bulgarian Empire. Old Church Slavonic spread to other South-Eastern, Central, and Eastern European Slavic territories, most notably Croatia, Serbia, Bohemia, Lesser Poland, and principalities of the Kievan Rus' – while retaining characteristically Eastern South Slavic linguistic features.

Later texts written in each of those territories began to take on characteristics of the local Slavic vernaculars, and by the mid-11th century Old Church Slavonic had diversified into a number of regional varieties (known as recensions). These local varieties are collectively known as the Church Slavonic language.[47]

Apart from use in the Slavic countries, Old Church Slavonic served as a liturgical language in the Romanian Orthodox Church, and also as a literary and official language of the princedoms of Wallachia and Moldavia (see Old Church Slavonic in Romania), before gradually being replaced by Romanian during the 16th to 17th centuries.

Church Slavonic maintained a prestigious status, particularly in Russia, for many centuries – among Slavs in the East it had a status analogous to that of Latin in Western Europe, but had the advantage of being substantially less divergent from the vernacular tongues of average parishioners.

Some Orthodox churches, such as the Bulgarian Orthodox Church, Russian Orthodox Church, Serbian Orthodox Church, Ukrainian Orthodox Church and Macedonian Orthodox Church – Ohrid Archbishopric, as well as several Eastern Catholic Churches[which?], still use Church Slavonic in their services and chants.[49]

Scripts

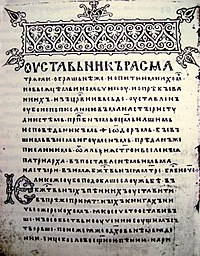

Initially Old Church Slavonic was written with the Glagolitic alphabet, but later Glagolitic was replaced by Cyrillic,[50] which was developed in the First Bulgarian Empire by a decree of Boris I of Bulgaria in the 9th century. Of the Old Church Slavonic canon, about two-thirds is written in Glagolitic.

The local Bosnian Cyrillic alphabet, known as Bosančica, was preserved in Bosnia and parts of Croatia, while a variant of the angular Glagolitic alphabet was preserved in Croatia. See Early Cyrillic alphabet for a detailed description of the script and information about the sounds it originally expressed.

Phonology

For Old Church Slavonic, the following segments are reconstructible.[51] A few sounds are given in Slavic transliterated form rather than in IPA, as the exact realisation is uncertain and often differs depending on the area that a text originated from.

Consonants

For English equivalents and narrow transcriptions of sounds, see Old Church Slavonic Pronunciation on Wiktionary.

| Labial | Dental | Palatal | Velar | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | nʲc | ||

| Plosive | voiceless | p | t | t'a | k |

| voiced | b | d | d'a | ɡ | |

| Affricate | voiceless | t͡s | t͡ʃ | ||

| voiced | d͡zb | ||||

| Fricative | voiceless | s | ʃ | x | |

| voiced | z | ʒ | |||

| Lateral | l | lʲc | |||

| Trill | r | rʲc | |||

| Approximant | v | j | |||

- ^a These phonemes were written and articulated differently in different recensions: as ⟨Ⱌ⟩ (/t͡s/) and ⟨Ⰷ⟩ (/d͡z/) in the Moravian recension, ⟨Ⱌ⟩ (/t͡s/) and ⟨Ⰸ⟩ (/z/) in the Bohemian recension, ⟨Ⱋ⟩/⟨щ⟩ () and ⟨ⰆⰄ⟩/⟨жд⟩ () in the Bulgarian recension(s). In Serbia, ⟨Ꙉ⟩ was used to denote both sounds. The abundance of Middle Ages toponyms featuring and in North Macedonia, Kosovo and the Torlak-speaking parts of Serbia indicates that at the time, the clusters were articulated as & as well, even though current reflexes are different.[52]

- ^b /dz/ appears mostly in early texts, becoming /z/ later on.

- ^c The distinction between /l/, /n/ and /r/, on one hand, and palatal /lʲ/, /nʲ/ and /rʲ/, on the other, is not always indicated in writing. When it is, it is shown by a palatization diacritic over the letter: ⟨ л҄ ⟩ ⟨ н҄ ⟩ ⟨ р҄ ⟩.

Vowels

For English equivalents and narrow transcriptions of sounds, see Old Church Slavonic Pronunciation on Wiktionary.

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Accent is not indicated in writing and must be inferred from later languages and from reconstructions of Proto-Slavic.

- ^a All front vowels were iotated word-initially and succeeding other vowels. The same sometimes applied for *a and *ǫ. In the Bulgarian region, an epinthetic *v was inserted before *ǫ in the place of iotation.

- ^b The distinction between /i/, /ji/ and /jɪ/ is rarely indicated in writing and must be inferred from reconstructions of Proto-Slavic. In Glagolitic, the three are written as <ⰻ>, <ⰹ>, and <ⰺ> respectively. In Cyrillic, /jɪ/ may sometimes be written as ı, and /ji/ as ї, although this is rarely the case.

- ^c Yers preceding *j became tense, this was inconsistently reflected in writing in the case of *ь (ex: чаꙗньѥ or чаꙗние, both pronounced ), but never with *ъ (which was always written as a yery).

- ^d Yery was the descendant of Proto-Blato-Slavic long *ū and was a high back unrounded vowel. Tense *ъ merged with *y, which gave rise to yery's spelling as <ъи> (later <ꙑ>, modern <ы>).

- ^e The yer vowels ь and ъ (ĭ and ŭ) are often called "ultrashort" and were lower, more centralised and shorter than their tense counterparts *i and *y. Both yers had a strong and a weak variant, with a yer always being strong if the next vowel is another yer. Weak yers disappeared in most positions in the word, already sporadically in the earliest texts but more frequently later on. Strong yers, on the other hand, merged with other vowels, particularly ĭ with e and ŭ with o, but differently in different areas.

- ^f The pronunciation of yat (ѣ/ě) differed by area. In Bulgaria it was a relatively open vowel, commonly reconstructed as /æ/, but further north its pronunciation was more closed and it eventually became a diphthong /je/ (e.g. in modern standard Bosnian, Croatian and Montenegrin, or modern standard Serbian spoken in Bosnia and Herzegovina, as well as in Czech — the source of the grapheme ě) or even /i/ in many areas (e.g. in Chakavian Croatian, Shtokavian Ikavian Croatian and Bosnian dialects or Ukrainian) or /e/ (modern standard Serbian spoken in Serbia).

- ^g *a was the descendant of Proto-Slavic long *o and was a low back unrounded vowel. Its iotated variant was often confused with *ě (in Glagolitic they are even the same letter: Ⱑ), so *a was probably fronted to *ě when it followed palatal consonants (this is still the case in Rhodopean dialects).

- ^h The exact articulation of the nasal vowels is unclear because different areas tend to merge them with different vowels. ę /ɛ̃/ is occasionally seen to merge with e or ě in South Slavic, but becomes ja early on in East Slavic. ǫ /ɔ̃/ generally merges with u or o, but in Bulgaria, ǫ was apparently unrounded and eventually merged with ъ.

Phonotactics

Several notable constraints on the distribution of the phonemes can be identified, mostly resulting from the tendencies occurring within the Common Slavic period, such as intrasyllabic synharmony and the law of open syllables. For consonant and vowel clusters and sequences of a consonant and a vowel, the following constraints can be ascertained:[53]

- Two adjacent consonants tend not to share identical features of manner of articulation

- No syllable ends in a consonant

- Every obstruent agrees in voicing with the following obstruent

- Velars do not occur before front vowels

- Phonetically palatalized consonants do not occur before certain back vowels

- The back vowels /y/ and /ъ/ as well as front vowels other than /i/ do not occur word-initially: the two back vowels take prothetic /v/ and the front vowels prothetic /j/. Initial /a/ may take either prothetic consonant or none at all.

- Vowel sequences are attested in only one lexeme (paǫčina 'spider's web') and in the suffixes /aa/ and /ěa/ of the imperfect

- At morpheme boundaries, the following vowel sequences occur: /ai/, /au/, /ao/, /oi/, /ou/, /oo/, /ěi/, /ěo/

Morphophonemic alternations

As a result of the first and the second Slavic palatalizations, velars alternate with dentals and palatals. In addition, as a result of a process usually termed iotation (or iodization), velars and dentals alternate with palatals in various inflected forms and in word formation.

| original | /k/ | /g/ | /x/ | /sk/ | /zg/ | /sx/ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| first palatalization and iotation | /č/ | /ž/ | /š/ | /št/ | /žd/ | /š/ |

| second palatalization | /c/ | /dz/ | /s/ | /sc/, /st/ | /zd/ | /sc/ |

| original | /b/ | /p/ | /sp/ | /d/ | /zd/ | /t/ | /st/ | /z/ | /s/ | /l/ | /sl/ | /m/ | /n/ | /sn/ | /zn/ | /r/ | /tr/ | /dr/ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| iotation | /bl'/ | /pl'/ | /žd/ | /žd/ | /št/ | /št/ | /ž/ | /š/ | /l'/ | /šl'/ | /ml'/ | /n'/ | /šn'/ | /žn'/ | /r'/ | /štr'/ | /ždr'/ |

In some forms the alternations of /c/ with /č/ and of /dz/ with /ž/ occur, in which the corresponding velar is missing. The dental alternants of velars occur regularly before /ě/ and /i/ in the declension and in the imperative, and somewhat less regularly in various forms after /i/, /ę/, /ь/ and /rь/.[54] The palatal alternants of velars occur before front vowels in all other environments, where dental alternants do not occur, as well as in various places in inflection and word formation described below.[55]

As a result of earlier alternations between short and long vowels in roots in Proto-Indo-European, Proto-Balto-Slavic and Proto-Slavic times, and of the fronting of vowels after palatalized consonants, the following vowel alternations are attested in OCS: /ь/ : /i/; /ъ/ : /y/ : /u/; /e/ : /ě/ : /i/; /o/ : /a/; /o/ : /e/; /ě/ : /a/; /ъ/ : /ь/; /y/ : /i/; /ě/ : /i/; /y/ : /ę/.[55]

Vowel:∅ alternations sometimes occurred as a result of sporadic loss of weak yer, which later occurred in almost all Slavic dialects. The phonetic value of the corresponding vocalized strong jer is dialect-specific.

Grammar

As an ancient Indo-European language, OCS has a highly inflective morphology. Inflected forms are divided in two groups, nominals and verbs. Nominals are further divided into nouns, adjectives and pronouns. Numerals inflect either as nouns or pronouns, with 1–4 showing gender agreement as well.

Nominals can be declined in three grammatical genders (masculine, feminine, neuter), three numbers (singular, plural, dual) and seven cases: nominative, vocative, accusative, instrumental, dative, genitive, and locative. There are five basic inflectional classes for nouns: o/jo-stems, a/ja-stems, i-stems, u-stems and consonant stems. Forms throughout the inflectional paradigm usually exhibit morphophonemic alternations.

Fronting of vowels after palatals and j yielded dual inflectional class o : jo and a : ja, whereas palatalizations affected stem as a synchronic process (N sg. vlьkъ, V sg. vlьče; L sg. vlьcě). Productive classes are o/jo-, a/ja- and i-stems. Sample paradigms are given in the table below:

| Singular | Dual | Plural | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gloss | Stem type | Nom | Voc | Acc | Gen | Loc | Dat | Instr | Nom/Voc/Acc | Gen/Loc | Dat/Instr | Nom/Voc | Acc | Gen | Loc | Dat | Instr |

| "city" | o m. | gradъ | grade | gradъ | grada | gradě | gradu | gradomь | grada | gradu | gradoma | gradi | grady | gradъ | graděxъ | gradomъ | grady |

| "knife" | Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Old_Slavonic_language|||||||||||||||||