A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Quran | |

|---|---|

| Arabic: ٱلْقُرْآن, romanized: al-Qurʾān | |

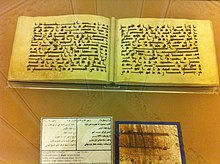

Two folios of the Birmingham Quran manuscript, an early manuscript written in Hijazi script likely dated within Muhammad's lifetime between c. 568–645 | |

| Information | |

| Religion | Islam |

| Language | Classical Arabic |

| Period | 610–632 CE |

| Chapters | 114 (list) See Surah |

| Verses | 6,348 (including the basmala) 6,236 (excluding the basmala) See Āyah |

| Full text | |

The Quran,[c] also romanized Qur'an or Koran,[d] is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation directly from God (All-h). It is organized in 114 chapters (surah, pl. suwer) which consist of individual verses (ayat). Besides its religious significance, it is widely regarded as the finest work in Arabic literature,[11][12][13] and has significantly influenced the Arabic language. It is also the object of a modern field of academic research known as Quranic studies.

Muslims believe the Quran was orally revealed by God to the final Islamic prophet Muhammad through the angel Gabriel incrementally over a period of some 23 years, beginning on the Night of Power, when Muhammad was 40, and concluding in 632, the year of his death. Muslims regard the Quran as Muhammad's most important miracle, a proof of his prophethood, and the culmination of a series of divine messages starting with those revealed to the first Islamic prophet Adam, including the Islamic holy books of the Torah, Psalms, and Gospel.

The Quran is believed by Muslims to be God's own divine speech providing a complete code of conduct across all facets of life. This has led Muslim theologians to fiercely debate whether the Quran was "created or uncreated." According to tradition, several of Muhammad's companions served as scribes, recording the revelations. Shortly after the prophet's death, the Quran was compiled on the order of the first caliph Abu Bakr (r. 632–634) by the companions, who had written down or memorized parts of it. Caliph Uthman (r. 644–656) established a standard version, now known as the Uthmanic codex, which is generally considered the archetype of the Quran known today. There are, however, variant readings, with mostly minor differences in meaning.

The Quran assumes the reader's familiarity with major narratives recounted in the Biblical and apocryphal texts. It summarizes some, dwells at length on others and, in some cases, presents alternative accounts and interpretations of events. The Quran describes itself as a book of guidance for humankind (2:185). It sometimes offers detailed accounts of specific historical events, and it often emphasizes the moral significance of an event over its narrative sequence.

Supplementing the Quran with explanations for some cryptic Quranic narratives, and rulings that also provide the basis for Islamic law in most denominations of Islam, are hadiths—oral and written traditions believed to describe words and actions of Muhammad. During prayers, the Quran is recited only in Arabic. Someone who has memorized the entire Quran is called a hafiz. Ideally, verses are recited with a special kind of prosody reserved for this purpose, called tajwid. During the month of Ramadan, Muslims typically complete the recitation of the whole Quran during tarawih prayers. In order to extrapolate the meaning of a particular Quranic verse, Muslims rely on exegesis, or commentary rather than a direct translation of the text.

| Quran |

|---|

Etymology and meaning

The word qur'ān appears about 70 times in the Quran itself,[14] assuming various meanings. It is a verbal noun (maṣdar) of the Arabic verb qara'a (قرأ) meaning 'he read' or 'he recited'. The Syriac equivalent is qeryānā (ܩܪܝܢܐ), which refers to 'scripture reading' or 'lesson'.[15] While some Western scholars consider the word to be derived from the Syriac, the majority of Muslim authorities hold the origin of the word is qara'a itself.[16] Regardless, it had become an Arabic term by Muhammad's lifetime.[16] An important meaning of the word is the 'act of reciting', as reflected in an early Quranic passage: "It is for Us to collect it and to recite it (qur'ānahu)."[17]

In other verses, the word refers to 'an individual passage recited '. Its liturgical context is seen in a number of passages, for example: "So when al-qur'ān is recited, listen to it and keep silent."[18] The word may also assume the meaning of a codified scripture when mentioned with other scriptures such as the Torah and Gospel.[19]

The term also has closely related synonyms that are employed throughout the Quran. Each synonym possesses its own distinct meaning, but its use may converge with that of qur'ān in certain contexts. Such terms include kitāb ('book'), āyah ('sign'), and sūrah ('scripture'); the latter two terms also denote units of revelation. In the large majority of contexts, usually with a definite article (al-), the word is referred to as the waḥy ('revelation'), that which has been "sent down" (tanzīl) at intervals.[20][21] Other related words include: dhikr ('remembrance'), used to refer to the Quran in the sense of a reminder and warning; and ḥikmah ('wisdom'), sometimes referring to the revelation or part of it.[16][e]

The Quran describes itself as 'the discernment' (al-furqān), 'the mother book' (umm al-kitāb), 'the guide' (huda), 'the wisdom' (hikmah), 'the remembrance' (dhikr), and 'the revelation' (tanzīl; 'something sent down', signifying the descent of an object from a higher place to lower place).[22] Another term is al-kitāb ('The Book'), though it is also used in the Arabic language for other scriptures, such as the Torah and the Gospels. The term mus'haf ('written work') is often used to refer to particular Quranic manuscripts but is also used in the Quran to identify earlier revealed books.[16]

History

Prophetic era

Islamic tradition relates that Muhammad received his first revelation in 610 CE in the Cave of Hira on the Night of Power[23] during one of his isolated retreats to the mountains. Thereafter, he received revelations over a period of 23 years. According to hadith (traditions ascribed to Muhammad)[f][24] and Muslim history, after Muhammad immigrated to Medina and formed an independent Muslim community, he ordered many of his companions to recite the Quran and to learn and teach the laws, which were revealed daily. It is related that some of the Quraysh who were taken prisoners at the Battle of Badr regained their freedom after they had taught some of the Muslims the simple writing of the time. Thus a group of Muslims gradually became literate. As it was initially spoken, the Quran was recorded on tablets, bones, and the wide, flat ends of date palm fronds. Most suras were in use amongst early Muslims since they are mentioned in numerous sayings by both Sunni and Shia sources, relating Muhammad's use of the Quran as a call to Islam, the making of prayer and the manner of recitation. However, the Quran did not exist in book form at the time of Muhammad's death in 632 at age 61–62.[16][25][26][27][28][29] There is agreement among scholars that Muhammad himself did not write down the revelation.[30]

Sahih al-Bukhari narrates Muhammad describing the revelations as, "Sometimes it is (revealed) like the ringing of a bell" and A'isha reported, "I saw the Prophet being inspired Divinely on a very cold day and noticed the sweat dropping from his forehead (as the Inspiration was over)."[g] Muhammad's first revelation, according to the Quran, was accompanied with a vision. The agent of revelation is mentioned as the "one mighty in power,"[32] the one who "grew clear to view when he was on the uppermost horizon. Then he drew nigh and came down till he was (distant) two bows' length or even nearer."[28][33] The Islamic studies scholar Welch states in the Encyclopaedia of Islam that he believes the graphic descriptions of Muhammad's condition at these moments may be regarded as genuine, because he was severely disturbed after these revelations. According to Welch, these seizures would have been seen by those around him as convincing evidence for the superhuman origin of Muhammad's inspirations. However, Muhammad's critics accused him of being a possessed man, a soothsayer or a magician since his experiences were similar to those claimed by such figures well known in ancient Arabia. Welch additionally states that it remains uncertain whether these experiences occurred before or after Muhammad's initial claim of prophethood.[34]

The Quran describes Muhammad as "ummi",[35] which is traditionally interpreted as 'illiterate', but the meaning is rather more complex. Medieval commentators such as al-Tabari (d. 923) maintained that the term induced two meanings: first, the inability to read or write in general; second, the inexperience or ignorance of the previous books or scriptures (but they gave priority to the first meaning). Muhammad's illiteracy was taken as a sign of the genuineness of his prophethood. For example, according to Fakhr al-Din al-Razi, if Muhammad had mastered writing and reading he possibly would have been suspected of having studied the books of the ancestors. Some scholars such as W. Montgomery Watt prefer the second meaning of ummi—they take it to indicate unfamiliarity with earlier sacred texts.[28][36]

The final verse of the Quran was revealed on the 18th of the Islamic month of Dhu al-Hijja in the year 10 A.H., a date that roughly corresponds to February or March 632. The verse was revealed after the Prophet finished delivering his sermon at Ghadir Khumm.

Compilation and preservation

Following Muhammad's death in 632, a number of his companions who memorized the Quran were killed in the Battle of al-Yamama by Musaylima. The first caliph, Abu Bakr (r. 632–634), subsequently decided to collect the book in one volume so that it could be preserved.[37] Zayd ibn Thabit (d. 655) was the person to collect the Quran since "he used to write the Divine Inspiration for Allah's Apostle".[38] Thus, a group of scribes, most importantly Zayd, collected the verses and produced a hand-written manuscript of the complete book. The manuscript according to Zayd remained with Abu Bakr until he died. Zayd's reaction to the task and the difficulties in collecting the Quranic material from parchments, palm-leaf stalks, thin stones (collectively known as suhuf, any written work containing divine teachings)[39] and from men who knew it by heart is recorded in earlier narratives. In 644, Muhammad's widow Hafsa bint Umar was entrusted with the manuscript until the third caliph, Uthman (r. 644–656),[38] requested the standard copy from her.[40] (According to historian Michael Cook, early Muslim narratives about the collection and compilation of the Quran sometimes contradict themselves. "Most ... make Uthman little more than an editor, but there are some in which he appears very much a collector, appealing to people to bring him any bit of the Quran they happen to possess." Some accounts also "suggest that in fact the material" Abu Bakr worked with "had already been assembled", which since he was the first caliph, would mean they were collected when Muhammad was still alive.)[41]

In about 650, Uthman began noticing slight differences in pronunciation of the Quran as Islam expanded beyond the Arabian Peninsula into Persia, the Levant, and North Africa. In order to preserve the sanctity of the text, he ordered a committee headed by Zayd to use Abu Bakr's copy and prepare a standard text of the Quran.[42][43] Thus, within 20 years of Muhammad's death (around 650 CE),[44] the complete Quran was committed to written form, a codex. That text became the model from which copies were made and promulgated throughout the urban centers of the Muslim world, and other versions are believed to have been destroyed.[42][45][46][47] The present form of the Quran text is accepted by Muslim scholars to be the original version compiled by Abu Bakr.[28][29][h][i]

This preservation of the Quran is considered one of the miracles of the Quran among the Islamic faithful.[j]

The Shia recite the Qur'an according to the qira'at of Hafs on authority of ‘Asim, which is the prevalent Qira’at in the Islamic world[53] and believe that the Quran was gathered and compiled by Muhammad during his lifetime.[54][55] It is claimed that the Shia had more than 1,000 hadiths ascribed to the Shia Imams which indicate the distortion of the Quran[56] and according to Etan Kohlberg, this belief about Quran was common among Shiites in the early centuries of Islam.[57] In his view, Ibn Babawayh was the first major Twelver author "to adopt a position identical to that of the Sunnis" and the change was a result of the "rise to power of the Sunni 'Abbasid caliphate," whence belief in the corruption of the Quran became untenable vis-a-vis the position of Sunni “orthodoxy”.[58] Alleged distortions to have been carried out to remove any references to the rights of Ali, the Imams and their supporters and the disapproval of enemies, such as Umayyads and Abbasids.[59]

Other personal copies of the Quran might have existed including Ibn Mas'ud's and Ubay ibn Ka'b's codex, none of which exist today.[16][42][60]

Academic research

Since Muslims could regard criticism of the Qur'an as a crime of apostasy punishable by death under sharia, it seemed impossible to conduct studies on the Qur'an that went beyond textual criticism.[61][62] Until the early 1970s,[63] non-Muslim scholars of Islam —while not accepting traditional explanations for divine intervention— accepted the above-mentioned traditional origin story in most details.[37]

Rasm: "ٮسم الله الرحمں الرحىم"

University of Chicago professor Fred Donner states that:[64]

here was a very early attempt to establish a uniform consonantal text of the Qurʾān from what was probably a wider and more varied group of related texts in early transmission.… After the creation of this standardized canonical text, earlier authoritative texts were suppressed, and all extant manuscripts—despite their numerous variants—seem to date to a time after this standard consonantal text was established.

Although most variant readings of the text of the Quran have ceased to be transmitted, some still are.[65][66] There has been no critical text produced on which a scholarly reconstruction of the Quranic text could be based.[k]

In 1972, in a mosque in the city of Sana'a, Yemen, manuscripts "consisting of 12,000 pieces" were discovered that were later proven to be the oldest Quranic text known to exist at the time. The Sana'a manuscripts contain palimpsests, manuscript pages from which the text has been washed off to make the parchment reusable again—a practice which was common in ancient times due to the scarcity of writing material. However, the faint washed-off underlying text (scriptio inferior) is still barely visible.[68] Studies using radiocarbon dating indicate that the parchments are dated to the period before 671 CE with a 99 percent probability.[69][70] The German scholar Gerd R. Puin has been investigating these Quran fragments for years. His research team made 35,000 microfilm photographs of the manuscripts, which he dated to the early part of the 8th century. Puin has noted unconventional verse orderings, minor textual variations, and rare styles of orthography, and suggested that some of the parchments were palimpsests which had been reused. Puin believed that this implied an evolving text as opposed to a fixed one.[71]

In 2015, a single folio of a very early Quran, dating back to 1370 years earlier, was discovered in the library of the University of Birmingham, England. According to the tests carried out by the Oxford University Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit, "with a probability of more than 95%, the parchment was from between 568 and 645". The manuscript is written in Hijazi script, an early form of written Arabic.[72] This possibly was one of the earliest extant exemplars of the Quran, but as the tests allow a range of possible dates, it cannot be said with certainty which of the existing versions is the oldest.[72] Saudi scholar Saud al-Sarhan has expressed doubt over the age of the fragments as they contain dots and chapter separators that are believed to have originated later.[73] The Birmingham manuscript holds significance amongst scholarship because of its early dating and potential overlap with the dominant tradition over the lifetime of Muhammad c. 570 to 632 CE[74] and used as evidence to support conventional wisdom and to refute the revisionists' views on the history of the writing of the Quran.[75]

Contents

The Quranic content is concerned with basic Islamic beliefs including the existence of God and the resurrection. Narratives of the early prophets, ethical and legal subjects, historical events of Muhammad's time, charity and prayer also appear in the Quran. The Quranic verses contain general exhortations regarding right and wrong and historical events are related to outline general moral lessons. Verses pertaining to natural phenomena have been interpreted by Muslims as an indication of the authenticity of the Quranic message.[76] The style of the Quran has been called "allusive", with commentaries needed to explain what is being referred to—"events are referred to, but not narrated; disagreements are debated without being explained; people and places are mentioned, but rarely named."[77]

Persian miniature (c. 1595), tinted drawing on paper

Many places, subjects and mythological figures in the culture of Arabs and many nations in their historical neighbourhoods, especially Judeo-Christian stories,[78] are included in the Quran with small allusions, references or sometimes small narratives such as firdaws, Seven sleepers, Queen of Sheba etc. However, some philosophers and scholars such as Mohammed Arkoun, who emphasize the mythological character of the language and content of the Quran, are met with rejectionist attitudes in Islamic circles.[79]

The stories of Yusuf and Zulaikha, Moses, Family of Amram (parents of Mary according to Quran) and mysterious hero[80][81][82][83] Dhul-Qarnayn ("the man with two horns") who built a barrier against Gog and Magog that will remain until the end of time are more detailed and longer stories. Apart from semi-historical events and characters such as King Solomon and David, about Jewish history as well as the exodus of the Israelites from Egypt, tales of the hebrew prophets accepted in Islam, such as Creation, the Flood, struggle of Abraham with Nimrod, sacrifice of his son occupy a wide place in the Quran.

The Quran assumes the reader's familiarity with major narratives recounted in the Biblical and apocryphal scriptures. It summarizes some, dwells at length on others and, in some cases, presents alternative accounts and interpretations of events.[84][85] The Quran describes itself as a book of guidance for humankind (2:185). It sometimes offers detailed accounts of specific historical events, and it often emphasizes the moral significance of an event over its narrative sequence.[86] Supplementing the Quran with explanations for some cryptic Quranic narratives, and rulings that also provide the basis for Islamic law in most denominations of Islam,[24][l]

Creation and God

The Quran uses cosmological and contingency arguments in various verses without referring to the terms to prove the existence of God. Therefore, the universe is originated and needs an originator, and whatever exists must have a sufficient cause for its existence. Besides, the design of the universe is frequently referred to as a point of contemplation: "It is He who has created seven heavens in harmony. You cannot see any fault in God's creation; then look again: Can you see any flaw?"[87][88]

The central theme of the Quran is monotheism. God is depicted as living, eternal, omniscient and omnipotent (see, e.g., Quran 2:20, 2:29, 2:255). God's omnipotence appears above all in his power to create. He is the creator of everything, of the heavens and the earth and what is between them (see, e.g., Quran 13:16, 2:253, 50:38, etc.). All human beings are equal in their utter dependence upon God, and their well-being depends upon their acknowledging that fact and living accordingly.[28][76]

Even though Muslims do not doubt about the existence and unity of God, they may have adopted different attitudes that have changed and developed throughout history regarding his nature (attributes), names and relationship with creation.

Prophets

In Islam, God speaks to people called prophets through a kind of revelation called wahy or through angels.(42:51) Although poetry (Shu'ara: 224) and prophecy (claiming to know the unseen or the future) are seen as despicable behavior in Islam, (7:188, 27:65) nubuwwah (Arabic: نبوة "prophethood") is seen as a duty imposed by God on individuals who have some characteristics such as intelligence, honesty, fortitude and justice. (See:Ismah) "Nothing is said to you that was not said to the messengers before you, that your lord has at his Command forgiveness as well as a most Grievous Penalty."[89]

Islam regards Abraham as a link in the chain of prophets that begins with Adam and culminates in Muhammad via Ishmael[90] and mentioned in 35 chapters of the Quran, more often than any other biblical personage apart from Moses.[91] Muslims regard him as an idol smasher, hanif,[92] an archetype of the perfect Muslim, and revered prophet and builder of the Kaaba in Mecca.[93] The Quran consistently refers to Islam as "the Religion of Abraham" (millat Ibrahim).[94] Besides Ishaq and Yaqub, Abraham is among the most honorable, excellent role model father for Muslims.[95][96][97]

In Islam, Eid-al-Adha is celebrated to commemorate Abraham's attempt to sacrifice his son by surrendering in line with his dream,(As-Saaffat; 100–107) which he accepted as the will of GOD.[98] In Judaism the story is perceived as a narrative designed to replace child sacrifice with animal sacrifice in general[99] or as a metaphor describing "sacrific animalistic nature",[100][101] Orthodox Islamic understanding considers animal sacrifice as a mandatory or strong sunnah for Muslims who meet certain conditions, on a certain date determined by the Hijri calendar every year.

Mūsā is a prominent prophet and messenger of God and is the most frequently mentioned individual in the Quran, with his name being mentioned 136 times and his life being narrated and recounted more than that of any other prophet.[102][103]

Ethico-religious concepts

Faith is a fundamental aspect of morality in the Quran, and scholars have tried to determine the semantic contents of "belief" and "believer" in the Quran.[104] The ethico-legal concepts and exhortations dealing with righteous conduct are linked to a profound awareness of God, thereby emphasizing the importance of faith, accountability, and the belief in each human's ultimate encounter with God. People are invited to perform acts of charity, especially for the needy. Believers who "spend of their wealth by night and by day, in secret and in public" are promised that they "shall have their reward with their Lord; on them shall be no fear, nor shall they grieve."[105]

It also affirms family life by legislating on matters of marriage, divorce, and inheritance. A number of practices, such as usury and gambling, are prohibited. The Quran is one of the fundamental sources of Islamic law (sharia). Some formal religious practices receive significant attention in the Quran including the salat and fasting in the month of Ramadan. As for the manner in which the prayer is to be conducted, the Quran refers to prostration.[37][106] The term chosen for charity, zakat, literally means purification implies that it is a self-purification.[107][108] In fiqh, the term fard is used for clear imperative provisions based on the Quran. However, it is not possible to say that the relevant verses are understood in the same way by all segments of Islamic commentators; For example, Hanafis accept 5 daily prayers as fard. However, some religious groups such as Quranists and Shiites, who do not doubt that the Quran existing today is a religious source, infer from the same verses that it is clearly ordered to pray 2 or 3 times,[109][110][111][112] not 5 times.

Although it is believed in Islam that the pre-Islamic prophets provided general guidance and that some books were sent down to them, their stories such as Lot and story with his daughters in the Bible conveyed from any source are called Israʼiliyyat and are met with suspicion.[113] The provisions that might arise from them, (such as the consumption of wine) could only be "abrogated provisions" (naskh).[114] The guidance of the Quran and Muhammad is considered absolute, universal and will continue until the end of time. However, today, this understanding is questioned in certain circles, it is claimed that the provisions and contents in sources such as the Quran and hadith, apart from general purposes,[115] are contents that reflect the general understanding and practices of that period,[116] and it is brought up to replace the sharia practices that pose problems in terms of today's ethic values[117][118] with new interpretations.

Eschatology

The doctrine of the last day and eschatology (the final fate of the universe) may be considered the second great doctrine of the Quran.[28] It is estimated that approximately one-third of the Quran is eschatological, dealing with the afterlife in the next world and with the day of judgment at the end of time.[119] The Quran does not assert a natural immortality of the human soul, since man's existence is dependent on the will of God: when he wills, he causes man to die; and when he wills, he raises him to life again in a bodily resurrection.[106]

In the Quran belief in the afterlife is often referred in conjunction with belief in God: "Believe in God and the last day"[120] emphasizing what is considered impossible is easy in the sight of God. A number of suras such as 44, 56, 75, 78, 81 and 101 are directly related to the afterlife and warn people to be prepared for the "imminent" day referred to in various ways. It is 'the Day of Judgment,' 'the Last Day,' 'the Day of Resurrection,' or simply 'the Hour.' Less frequently it is 'the Day of Distinction', 'the Day of the Gathering' or 'the Day of the Meeting'.[28]

"Signs of the hour" in the Quran are a "Beast of the Earth" will arise (27:82); the nations Gog and Magog will break through their ancient barrier wall and sweep down to scourge the earth (21:96-97); and Jesus is "a sign of the hour." Despite the uncertainty of the time is emphasized with the statement that it is only in the presence of God,(43:61) there is a rich eschatological literature in the Islamic world and doomsday prophecies in the Islamic world are heavily associated with "round" numbers.[121] Said Nursi interpreted the expressions in the Quran and hadiths as metaphorical or allegorical symbolizations[122] and benefited from numerological methods applied to some ayah/hadith fragments in his own prophecies.[123]

In the apocalyptic scenes, clues are included regarding the nature, structure and dimensions of the celestial bodies as perceived in the Quran: While the stars are lamps illuminating the sky in ordinary cases, turns into stones (Al-Mulk 1-5) or (shahap; meteor, burning fire) (al-Jinn 9) thrown at demons that illegally ascend to the sky; When the time of judgment comes, they spill onto the earth, but this does not mean that life on earth ends; People run left and right in fear.(At-Takwir 1-7) Then a square is set up and the king or lord of the day;(māliki yawmi-d-dīn)[i] comes and shows his shin;[127][128] looks are fearful, are invited to prostration; but those invited in the past but stayed away, cannot do this.(Al-Qalam 42-43)

Some researchers have no hesitation that many doomsday concepts, some of which are also used in the Quran, such as firdaws, kawthar, jahannam, maalik have come from foreign cultures through historical evolution.[129]

Science and the Quran

According to M. Shamsher Ali, there are around 750 verses in the Quran dealing with natural phenomena and many verses of the Quran ask mankind to study nature, and this has been interpreted to mean an encouragement for scientific inquiry,[130] and of the truth. Some include, “Travel throughout the earth and see how He brings life into being” (Q29:20), “Behold in the creation of the heavens and the earth, and the alternation of night and day, there are indeed signs for men of understanding ...” (Q3:190) The astrophysicist Nidhal Guessoum writes: "The Qur'an draws attention to the danger of conjecturing without evidence (And follow not that of which you have not the knowledge of... 17:36) and in several different verses asks Muslims to require proofs (Say: Bring your proof if you are truthful 2:111)." He associates some scientific contradictions that can be seen in the Quran with a superficial reading of the Quran.[131]

Ismail al-Faruqi and Taha Jabir Alalwani are of the view that any reawakening of the Muslim civilization must start with the Quran; however, the biggest obstacle on this route is the "centuries old heritage of tafseer and other disciplines which inhibit a "universal conception" of the Quran's message.[132] Author Rodney Stark argues that Islam's lag behind the West in scientific advancement after (roughly) 1500 AD was due to opposition by traditional ulema to efforts to formulate systematic explanation of natural phenomenon with "natural laws." He claims that they believed such laws were blasphemous because they limit "God's freedom to act" as He wishes.[133]

Taner Edis wrote many Muslims appreciate technology and respect the role that science plays in its creation. As a result, he says there is a great deal of Islamic pseudoscience attempting to reconcile this respect with religious beliefs.[134] This is because, according to Edis, true criticism of the Quran is almost non-existent in the Muslim world. While Christianity is less prone to see its Holy Book as the direct word of God, fewer Muslims will compromise on this idea – causing them to believe that scientific truths must appear in the Quran.[134]

Starting in the 1970s and 80s, the idea of presence of scientific evidence in the Quran became popularized as ijaz (miracle) literature, also called "Bucailleism", and began to be distributed through Muslim bookstores and websites.[135][136] The movement contends that the Quran abounds with "scientific facts" that appeared centuries before their discovery and promotes Islamic creationism. According to author Ziauddin Sardar, the ijaz movement has created a "global craze in Muslim societies", and has developed into an industry that is "widespread and well-funded".[135][136][137] Individuals connected with the movement include Abdul Majeed al-Zindani, who established the Commission on Scientific Signs in the Quran and Sunnah; Zakir Naik, the Indian televangelist; and Adnan Oktar, the Turkish creationist.[135]

Enthusiasts of the movement argue that among the miracles found in the Quran are "everything, from relativity, quantum mechanics, Big Bang theory, black holes and pulsars, genetics, embryology, modern geology, thermodynamics, even the laser and hydrogen fuel cells".[135] Zafar Ishaq Ansari terms the modern trend of claiming the identification of "scientific truths" in the Quran as the "scientific exegesis" of the holy book.[138] In 1983, Keith L. Moore, had a special edition published of his widely used textbook on Embryology (The Developing Human: Clinically Oriented Embryology), co-authored by Abdul Majeed al-Zindani with Islamic Additions,[139] interspersed pages of "embryology-related Quranic verse and hadith" by al-Zindani into Moore's original work.[140] Ali A. Rizvi studying the textbook of Moore and al-Zindani found himself "confused" by "why Moore was so 'astonished by'" the Quranic references, which Rizvi found "vague", and insofar as they were specific, preceded by the observations of Aristotle and the Ayr-veda,[141] or easily explained by "common sense".[140][142]

Critics argue, verses that proponents say explain modern scientific facts, about subjects such as biology, the origin and history of the Earth, and the evolution of human life, contain fallacies and are unscientific.[136][143] As of 2008, both Muslims and non-Muslims have disputed whether there actually are "scientific miracles" in the Quran. Muslim critics of the movement include Indian Islamic theologian Maulana Ashraf ‘Ali Thanvi, Muslim historian Syed Nomanul Haq, Muzaffar Iqbal, president of Center for Islam and Science in Alberta, Canada, and Egyptian Muslim scholar Khaled Montaser.[144]

Text and arrangement

The Quran consists of 114 chapters of varying lengths, known as a sūrah. Chapters are classified as Meccan or Medinan, depending on whether the verses were revealed before or after the migration of Muhammad to the city of Medina. However, a sūrah classified as Medinan may contain Meccan verses in it and vice versa. Sūrah names are derived from a name or quality discussed in the text, or from the first letters or words of the sūrah. Chapters are not arranged in chronological order, rather the chapters appear to be arranged roughly in order of decreasing size. Some scholars argue the sūrahs are arranged according to a certain pattern.[145] Each sūrah except the ninth starts with the Bismillah (بِسْمِ ٱللَّٰهِ ٱلرَّحْمَٰنِ ٱلرَّحِيمِ), an Arabic phrase meaning 'In the name of God.' There are, however, still 114 occurrences of the Bismillah in the Quran, due to its presence in Quran 27:30 as the opening of Solomon's letter to the Queen of Sheba.[146][147]

Each sūrah consists of verses, known as āyāt, which originally means a 'sign' or 'evidence' sent by God. The number of verses differs from sūrah to sūrah. An individual verse may be just a few letters or several lines. The total number of verses in the most popular Hafs Quran is 6,236;[m] however, the number varies if the bismillahs are counted separately.

In addition of the division into chapters, there are various ways of dividing Quran into parts of approximately equal length for convenience in reading. The 30 juz' (plural ajzāʼ) can be used to read through the entire Quran in a month. A juz' is sometimes further divided into two ḥizb (plural aḥzāb), and each hizb subdivided into four rubʻ al-ahzab. The Quran is also divided into seven approximately equal parts, manzil (plural manāzil), for it to be recited in a week.[16]

A different structure is provided by semantic units resembling paragraphs and comprising roughly ten āyāt each. Such a section is called a ruku.

The Muqattaʿat (Arabic: حروف مقطعات ḥurūf muqaṭṭaʿāt, 'disjoined letters, disconnected letters';[149] also 'mysterious letters')[150] are combinations of between one and five Arabic letters figuring at the beginning of 29 out of the 114 chapters of the Quran just after the basmala.[150] The letters are also known as fawātih (فواتح), or 'openers', as they form the opening verse of their respective suras. Four surahs are named for their muqatta'at: Ṭāʾ-Hāʾ, Yāʾ-Sīn, Ṣād, and Qāf. The original significance of the letters is unknown. Tafsir (exegesis)[151] has interpreted them as abbreviations for either names or qualities of God or for the names or content of the respective surahs. According to Rashad Khalifa, those letters are Quranic initials for a hypothetical mathematical code in the Quran, namely the Quran code[152] but this has been criticized by Bilal Philips as a hoax based on falsified data, misinterpretations of the Quran's text.[153]

According to one estimate the Quran consists of 77,430 words, 18,994 unique words, 12,183 stems, 3,382 lemmas and 1,685 roots.[154]

Literary style

The Quran's message is conveyed with various literary structures and devices. In the original Arabic, the suras and verses employ phonetic and thematic structures that assist the audience's efforts to recall the message of the text. Muslims[who?] assert (according to the Quran itself) that the Quranic content and style is inimitable.[155]

The language of the Quran has been described as "rhymed prose" as it partakes of both poetry and prose; however, this description runs the risk of failing to convey the rhythmic quality of Quranic language, which is more poetic in some parts and more prose-like in others. Rhyme, while found throughout the Quran, is conspicuous in many of the earlier Meccan suras, in which relatively short verses throw the rhyming words into prominence. The effectiveness of such a form is evident for instance in Sura 81, and there can be no doubt that these passages impressed the conscience of the hearers. Frequently a change of rhyme from one set of verses to another signals a change in the subject of discussion. Later sections also preserve this form but the style is more expository.[156][157]

The Quranic text seems to have no beginning, middle, or end, its nonlinear structure being akin to a web or net.[16] The textual arrangement is sometimes considered to exhibit lack of continuity, absence of any chronological or thematic order and repetitiousness.[n][o] Michael Sells, citing the work of the critic Norman O. Brown, acknowledges Brown's observation that the seeming disorganization of Quranic literary expression—its scattered or fragmented mode of composition in Sells's phrase—is in fact a literary device capable of delivering profound effects as if the intensity of the prophetic message were shattering the vehicle of human language in which it was being communicated.[160][161] Sells also addresses the much-discussed repetitiveness of the Quran, seeing this, too, as a literary device.

A text is self-referential when it speaks about itself and makes reference to itself. According to Stefan Wild, the Quran demonstrates this metatextuality by explaining, classifying, interpreting and justifying the words to be transmitted. Self-referentiality is evident in those passages where the Quran refers to itself as revelation (tanzil), remembrance (dhikr), news (naba'), criterion (furqan) in a self-designating manner (explicitly asserting its Divinity, "And this is a blessed Remembrance that We have sent down; so are you now denying it?"),[162] or in the frequent appearance of the "Say" tags, when Muhammad is commanded to speak (e.g., "Say: 'God's guidance is the true guidance'", "Say: 'Would you then dispute with us concerning God?'"). According to Wild the Quran is highly self-referential. The feature is more evident in early Meccan suras.[163]

Significance in Islam

| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

|