A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

Mga Pilipino | |

|---|---|

| |

| Total population | |

| c. 115 million[1] (c. 11–12 million in Filipino diaspora)[2][3] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Philippines c. 100 million figures below are for various years | |

| United States | 4,037,564[4] |

| Canada | 957,355 (2021)[5] |

| Saudi Arabia | 938,490[6] |

| United Arab Emirates | 679,819[7] |

| Malaysia | 325,089[8] |

| Japan | 322,046 (2023)[9] |

| Australia | 300,620[10] |

| Kuwait | 241,999[11] (December 31, 2020) |

| Qatar | 236,000[12] |

| Spain | 200,000 (2018)[13] |

| United Kingdom | 200,000 (2017)[14] |

| Singapore | 200,000[15] |

| Italy | 167,859[16] |

| Taiwan | 152,529 (2023)[17] |

| Hong Kong | 130,810[18] |

| Germany | 65,000[19] |

| South Korea | 63,464[20] |

| France | 50,000 (2020)[21] |

| New Zealand | 72,612 (2018)[22] |

| Bahrain | 40,000[23] |

| Israel | 31,000[24] |

| Brazil | 30,368 (2022)[25] |

| Netherlands | 25,365 (2021)[26] |

| Papua New Guinea | 25,000[27] |

| Belgium | 19,772 (2019)[28] |

| Macau | 14,544[29] |

| Sweden | 13,000[30] |

| Ireland | 12,791[31] |

| Austria | 12,474[32] |

| Norway | 12,262[33] |

| China | 12,254[34] |

| Switzerland | 10,000[35] |

| Indonesia | 7,400 (2022)[36] |

| Kazakhstan | 7,000[37] |

| Palau | 7,000[38] |

| Greece | 6,500[39] |

| Finland | 5,665[40] |

| Turkey | 5,500[41] |

| Russia | 5,000[42] |

| Nigeria | 4,500[43] |

| Cayman Islands | 4,119[44] |

| Morocco | 3,000[45] |

| Iceland | 2,900[46] |

| Finland | 2,114[47] |

| Languages | |

| English, Filipino/Tagalog and other indigenous languages | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Roman Catholicism[48] Minority others are: | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Austronesian peoples, Native Indonesian | |

Filipinos (Filipino: Mga Pilipino)[49] are citizens or people identified with the country of the Philippines. The majority of Filipinos today are predominantly Catholic[50] and come from various Austronesian peoples, all typically speaking Filipino, English, or other Philippine languages. Despite formerly being subject to Spanish colonialism, only around 2–4% of Filipinos are fluent in Spanish.[51] Currently, there are more than 185 ethnolinguistic groups in the Philippines each with its own language, identity, culture, tradition, and history.

Names

The name Filipino, as a demonym, was derived from the term las Islas Filipinas 'the Philippine Islands',[52] the name given to the archipelago in 1543 by the Spanish explorer and Dominican priest Ruy López de Villalobos, in honor of Philip II of Spain.[53] During the Spanish colonial period, natives of the Philippine islands were usually known in the Philippines itself by the generic terms indio ("Indian (native of the East Indies)") or indigena 'indigenous',[54] while the generic term chino ("Chinese"),[55][56] short for indio chino was used in Spanish America to differentiate from the Native American indios of the Spanish colonies in the Americas and the West Indies. The term Filipino was sometimes added by Spanish writers to distinguish the indio chino native of the Philippine archipelago from the indio of the Spanish colonies in the Americas, which were free people and legally barred from being used as slaves, unlike those from the Philippines.[55] [57][53] The term Indio Filipino appears as a term of self-identification beginning in the 18th century.[53]

In 1955, Agnes Newton Keith wrote that a 19th century edict prohibited the use of the word "Filipino" to refer to indios. This reflected popular belief, although no such edict has been found.[53] The idea that the term Filipino was not used to refer to indios until the 19th century has also been mentioned by historians such as Salah Jubair[58] and Renato Constantino.[59] However, in a 1994 publication the historian William Henry Scott identified instances in Spanish writing where "Filipino" did refer to "indio" natives.[60] Instances of such usage include the Relación de las Islas Filipinas (1604) of Pedro Chirino, in which he wrote chapters entitled "Of the civilities, terms of courtesy, and good breeding among the Filipinos" (Chapter XVI), "Of the Letters of the Filipinos" (Chapter XVII), "Concerning the false heathen religion, idolatries, and superstitions of the Filipinos" (Chapter XXI), "Of marriages, dowries, and divorces among the Filipinos" (Chapter XXX),[61] while also using the term "Filipino" to refer unequivocally to the non-Spaniard natives of the archipelago like in the following sentence:

The first and last concern of the Filipinos in cases of sickness was, as we have stated, to offer some sacrifice to their anitos or diwatas, which were their gods.[62]

— Pedro Chirino, Relación de las Islas Filipinas

In the Crónicas (1738) of Juan Francisco de San Antonio, the author devoted a chapter to "The Letters, languages and politeness of the Philippinos", while Francisco Antolín argued in 1789 that "the ancient wealth of the Philippinos is much like that which the Igorots have at present".[53] These examples prompted the historian William Henry Scott to conclude that during the Spanish colonial period:

the people of the Philippines were called Filipinos when they were practicing their own culture—or, to put it another way, before they became indios.[53]

— William Henry Scott, Barangay- Sixteenth Century Philippine Culture and Society

While the Philippine-born Spaniards during the 19th century began to be called españoles filipinos, logically contracted to just Filipino, to distinguish them from the Spaniards born in Spain, they themselves resented the term, preferring to identify themselves as "hijo/s del país" ("sons of the country").[53]

In the latter half of the 19th century, ilustrados, an educated class of mestizos (both Spanish mestizos and Sangley Chinese mestizos, especially Chinese mestizos) and indios arose whose writings are credited with building Philippine nationalism. These writings are also credited with transforming the term Filipino to one which refers to everyone born in the Philippines,[63][64] especially during the Philippine Revolution and American Colonial Era and the term shifting from a geographic designation to a national one as a citizenship nationality by law.[63][59] Historian Ambeth Ocampo has suggested that the first documented use of the word Filipino to refer to Indios was the Spanish-language poem A la juventud filipina, published in 1879 by José Rizal.[65] Writer and publisher Nick Joaquin has asserted that Luis Rodríguez Varela was the first to describe himself as Filipino in print.[66] Apolinario Mabini (1896) used the term Filipino to refer to all inhabitants of the Philippines. Father Jose Burgos earlier called all natives of the archipelago as Filipinos.[67] In Wenceslao Retaña's Diccionario de filipinismos, he defined Filipinos as follows,[68]

todos los nacidos en Filipinas sin distincion de origen ni de raza.

All those born in the Philippines without distinction of origin or race.— Wenceslao E. Retaña, Diccionario De Filipinismos: Con La Revisión De Lo Que Al Respecto Lleva Publicado La Real Academia Española

American authorities during the American Colonial Era also started to colloquially use the term Filipino to refer to the native inhabitants of the archipelago,[69] but despite this, it became the official term for all citizens of the sovereign independent Republic of the Philippines, including non-native inhabitants of the country as per the Philippine nationality law.[53] However, the term has been rejected as an identification in some instances by minorities who did not come under Spanish control, such as the Igorot and Muslim Moros.[53][59]

The lack of the letter "F" in the 1940–1987 standardized Tagalog alphabet (Abakada) caused the letter "P" to be substituted for "F", though the alphabets or writing scripts of some non-Tagalog ethnic groups included the letter "F". Upon official adoption of the modern, 28-letter Filipino alphabet in 1987, the term Filipino was preferred over Pilipino.[citation needed] Locally, some still use "Filipino" to refer to the people and "Pilipino" to refer to the language, but in international use "Filipino" is the usual form for both.

A number of Filipinos refer to themselves colloquially as "Pinoy" (feminine: "Pinay"), which is a slang word formed by taking the last four letters of "Filipino" and adding the diminutive suffix "-y". Or the non-gender or gender fluid form Pinxy.

In 2020, the neologism Filipinx appeared; a demonym applied only to those of Filipino heritage in the diaspora and specifically referring to and coined by Filipino Americans[citation needed] imitating Latinx, itself a recently coined gender-inclusive alternative to Latino or Latina. An online dictionary made an entry of the term, applying it to all Filipinos within the Philippines or in the diaspora.[70] In actual practice, however, the term is unknown among and not applied to Filipinos living in the Philippines, and Filipino itself is already treated as gender-neutral. The dictionary entry resulted in confusion, backlash and ridicule from Filipinos residing in the Philippines who never identified themselves with the foreign term.[71][72]

Native Filipinos were also called Manilamen (or Manila men) by English-speaking regions or Tagalas by Spanish-speakers during the colonial era. They were mostly sailors and pearl-divers and established communities in various ports around the world.[73][74] One of the notable settlements of Manilamen is the community of Saint Malo, Louisiana, founded at around 1763 to 1765 by escaped slaves and deserters from the Spanish Navy.[75][76][77][78] There were also significant numbers of Manilamen in Northern Australia and the Torres Strait Islands in the late 1800s who were employed in the pearl hunting industries.[79][80]

In Mexico (especially in the Mexican states of Guerrero and Colima), Filipino immigrants arriving to New Spain during the 16th and 17th centuries via the Manila galleons were called chino, which led to the confusion of early Filipino immigrants with that of the much later Chinese immigrants to Mexico from the 1880s to the 1940s. A genetic study in 2018 has also revealed that around one-third of the population of Guerrero have 10% Filipino ancestry.[81][82]

History

Prehistory

The oldest archaic human remains in the Philippines are the "Callao Man" specimens discovered in 2007 in the Callao Cave in Northern Luzon. They were dated in 2010 through uranium-series dating to the Late Pleistocene, c. 67,000 years old. The remains were initially identified as modern human, but after the discovery of more specimens in 2019, they have been reclassified as being members of a new species – Homo luzonensis.[83][84]

The oldest indisputable modern human (Homo sapiens) remains in the Philippines are the "Tabon Man" fossils discovered in the Tabon Caves in the 1960s by Robert B. Fox, an anthropologist from the National Museum. These were dated to the Paleolithic, at around 26,000 to 24,000 years ago. The Tabon Cave complex also indicates that the caves were inhabited by humans continuously from at least 47,000 ± 11,000 years ago to around 9,000 years ago.[85][86] The caves were also later used as a burial site by unrelated Neolithic and Metal Age cultures in the area.[87]

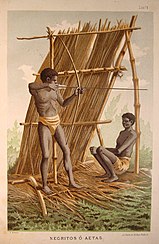

The Tabon Cave remains (along with the Niah Cave remains of Borneo and the Tam Pa Ling remains of Laos) are part of the "First Sundaland People", the earliest branch of anatomically modern humans to reach Island Southeast Asia via the Sundaland land bridge. They entered the Philippines from Borneo via Palawan at around 50,000 to 40,000 years ago. Their descendants are collectively known as the Negrito people, although they are highly genetically divergent from each other. Philippine Negritos show a high degree of Denisovan Admixture, similar to Papuans and Indigenous Australians, in contrast to Malaysian and Andamanese Negritos (the Orang Asli). This indicates that Philippine Negritos, Papuans, and Indigenous Australians share a common ancestor that admixed with Denisovans at around 44,000 years ago.[88] Negritos include ethnic groups like the Aeta (including the Agta, Arta, Dumagat, etc.) of Luzon, the Ati of Western Visayas, the Batak of Palawan, and the Mamanwa of Mindanao. Today they comprise just 0.03% of the total Philippine population.[89]

After the Negritos, were two early Paleolithic migrations from East Asian (basal Austric, an ethnic group which includes Austroasiatics) people, they entered the Philippines at around 15,000 and 12,000 years ago, respectively. Like the Negritos, they entered the Philippines via the Sundaland land bridge in the last ice age. They retain partial genetic signals among the Manobo people and the Sama-Bajau people of Mindanao.[90]

The last wave of prehistoric migrations to reach the Philippines was the Austronesian expansion which started in the Neolithic at around 4,500 to 3,500 years ago, when a branch of Austronesians from Taiwan (the ancestral Malayo-Polynesian-speakers) migrated to the Batanes Islands and Luzon. They spread quickly throughout the rest of the islands of the Philippines and became the dominant ethnolinguistic group. They admixed with the earlier settlers, resulting in the modern Filipinos – which though predominantly genetically Austronesian still show varying genetic admixture with Negritos (and vice versa for Negrito ethnic groups which show significant Austronesian admixture).[91][92] Austronesians possessed advanced sailing technologies and colonized the Philippines via sea-borne migration, in contrast to earlier groups.[93][94]

Austronesians from the Philippines also later settled Guam and the other islands of Maritime Southeast Asia, and parts of Mainland Southeast Asia. From there, they colonized the rest of Austronesia, which in modern times include Micronesia, coastal New Guinea, Island Melanesia, Polynesia, and Madagascar, in addition to Maritime Southeast Asia and Taiwan.[94][95]

The connections between the various Austronesian peoples have also been known since the colonial era due to shared material culture and linguistic similarities of various peoples of the islands of the Indo-Pacific, leading to the designation of Austronesians as the "Malay race" (or the "Brown race") during the age of scientific racism by Johann Friedrich Blumenbach.[96][97][98] Due to the colonial American education system in the early 20th century, the term "Malay race" is still used incorrectly in the Philippines to refer to the Austronesian peoples, leading to confusion with the non-indigenous Melayu people.[99][100][101][102]

Archaic epoch (to 1565)

Since at least the 3rd century, various ethnic groups established several communities. These were formed by the assimilation of various native Philippine kingdoms.[89] South Asian and East Asian people together with the people of the Indonesian archipelago and the Malay Peninsula, traded with Filipinos and introduced Hinduism and Buddhism to the native tribes of the Philippines. Most of these people stayed in the Philippines where they were slowly absorbed into local societies.

Many of the barangay (tribal municipalities) were, to a varying extent, under the de jure jurisprudence of one of several neighboring empires, among them the Malay Srivijaya, Javanese Majapahit, Brunei, Malacca, Tamil Chola, Champa and Khmer empires, although de facto had established their own independent system of rule. Trading links with Sumatra, Borneo, Java, Cambodia, Malay Peninsula, Indochina, China, Japan, India and Arabia. A thalassocracy had thus emerged based on international trade.

Even scattered barangays, through the development of inter-island and international trade, became more culturally homogeneous by the 4th century. Hindu-Buddhist culture and religion flourished among the noblemen in this era.

In the period between the 7th to the beginning of the 15th centuries, numerous prosperous centers of trade had emerged, including the Kingdom of Namayan which flourished alongside Manila Bay,[103][104] Cebu, Iloilo,[105] Butuan, the Kingdom of Sanfotsi situated in Pangasinan, the Kingdom of Luzon now known as Pampanga which specialized in trade with most of what is now known as Southeast Asia and with China, Japan and the Kingdom of Ryukyu in Okinawa.

From the 9th century onwards, a large number of Arab traders from the Middle East settled in the Malay Archipelago and intermarried with the local Malay, Bruneian, Malaysian, Indonesian and Luzon and Visayas indigenous populations.[106]

In the years leading up to 1000 AD, there were already several maritime societies existing in the islands but there was no unifying political state encompassing the entire Philippine archipelago. Instead, the region was dotted by numerous semi-autonomous barangays (settlements ranging in size from villages to city-states) under the sovereignty of competing thalassocracies ruled by datus, rajahs or sultans[107] or by upland agricultural societies ruled by "petty plutocrats". Nations such as the Wangdoms of Pangasinan and Ma-i as well as Ma-i's subordinates, the Barangay states of Pulilu and Sandao; the Kingdoms of Maynila, Namayan, and Tondo; the Kedatuans of Madja-as, Dapitan, and Cainta; the Rajahnates of Cebu, Butuan and Sanmalan; and the Sultanates of Buayan, Maguindanao, Lanao and Sulu; existed alongside the highland societies of the Ifugao and Mangyan.[108][109][110][111] Some of these regions were part of the Malayan empires of Srivijaya, Majapahit and Brunei.[112][113][114]

-

Tagalog maharlika, c.1590 Boxer Codex

-

Tagalog maginoo, c.1590 Boxer Codex

-

Visayan kadatuan, c.1590 Boxer Codex

-

Visayan timawa, c.1590 Boxer Codex

-

Visayan pintados (tattooed), c. 1590 Boxer Codex

-

Visayan uripon (slaves), c. 1590 Boxer Codex

Historic caste systems

Datu – The Tagalog maginoo, the Kapampangan ginu and the Visayan tumao were the nobility social class among various cultures of the pre-colonial Philippines. Among the Visayans, the tumao were further distinguished from the immediate royal families or a ruling class.

Timawa – The timawa class were free commoners of Luzon and the Visayas who could own their own land and who did not have to pay a regular tribute to a maginoo, though they would, from time to time, be obliged to work on a datu's land and help in community projects and events. They were free to change their allegiance to another datu if they married into another community or if they decided to move.

Maharlika – Members of the Tagalog warrior class known as maharlika had the same rights and responsibilities as the timawa, but in times of war they were bound to serve their datu in battle. They had to arm themselves at their own expense, but they did get to keep the loot they took. Although they were partly related to the nobility, the maharlikas were technically less free than the timawas because they could not leave a datu's service without first hosting a large public feast and paying the datu between 6 and 18 pesos in gold – a large sum in those days.

Alipin – Commonly described as "servant" or "slave". However, this is inaccurate. The concept of the alipin relied on a complex system of obligation and repayment through labor in ancient Philippine society, rather than on the actual purchase of a person as in Western and Islamic slavery. Members of the alipin class who owned their own houses were more accurately equivalent to medieval European serfs and commoners.

By the 15th century, Arab and Indian missionaries and traders from Malaysia and Indonesia brought Islam to the Philippines, where it both replaced and was practiced together with indigenous religions. Before that, indigenous tribes of the Philippines practiced a mixture of Animism, Hinduism and Buddhism. Native villages, called barangays were populated by locals called Timawa (Middle Class/freemen) and Alipin (servants and slaves). They were ruled by Rajahs, Datus and Sultans, a class called Maginoo (royals) and defended by the Maharlika (Lesser nobles, royal warriors and aristocrats).[89] These Royals and Nobles are descended from native Filipinos with varying degrees of Indo-Aryan and Dravidian, which is evident in today's DNA analysis among South East Asian Royals. This tradition continued among the Spanish and Portuguese traders who also intermarried with the local populations.[115]

Spanish colonisation and rule (1521–1898)

The first census in the Philippines was in 1591, based on tributes collected. The tributes counted the total founding population of the Spanish-Philippines as 667,612 people.[116]: 177 [117][118] 20,000 were Chinese migrant traders,[119] at different times: around 15,600 individuals were Latino soldier-colonists who were cumulatively sent from Peru and Mexico and they were shipped to the Philippines annually,[120][121] 3,000 were Japanese residents,[122] and 600 were pure Spaniards from Europe.[123] There was a large but unknown number of South Asian Filipinos, as the majority of the slaves imported into the archipelago were from Bengal and Southern India,[124] adding Dravidian speaking South Indians and Indo-European speaking Bengalis into the ethnic mix.

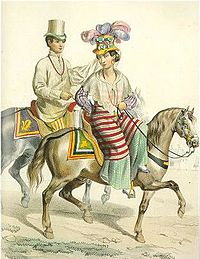

The Philippines was Colonised by the Spanish. The arrival of Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan (Portuguese: Fernão de Magalhães) in 1521 began a period of European colonization. During the period of Spanish colonialism, the Philippines was part of the Viceroyalty of New Spain, which was governed and administered from Mexico City. Early Spanish settlers were mostly explorers, soldiers, government officials and religious missionaries born in Spain and Mexico. Most Spaniards who settled were of Basque ancestry,[125] but there were also settlers of Andalusian, Catalan, and Moorish descent.[126] The Peninsulares (governors born in Spain), mostly of Castilian ancestry, settled in the islands to govern their territory. Most settlers married the daughters of rajahs, datus and sultans to reinforce the colonization of the islands. The Ginoo and Maharlika castes (royals and nobles) in the Philippines prior to the arrival of the Spanish formed the privileged Principalía (nobility) during the early Spanish period.

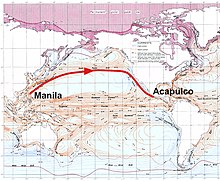

The arrival of the Spaniards to the Philippines, especially through the commencement of the Manila-Acapulco Galleon Trade that connected the Philippines through Manila to Acapulco in Mexico, attracted new waves of immigrants from China, as Manila was already previously connected to the Maritime Silk Road and Maritime Jade Road, as shown in the Selden Map, from Quanzhou and Zhangzhou in Southern Fujian to Manila, maritime trade flourished during the Spanish period, especially as Manila was connected to the ports of Southern Fujian, such as Yuegang (the old port of Haicheng in Zhangzhou, Fujian).[127][128] The Spanish recruited thousands of Chinese migrant workers from "Chinchew" (Quanzhou), "Chiõ Chiu" (Zhangzhou), "Canton" (Guangzhou), and Macau called sangleys (from Hokkien Chinese: 生理; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Sng-lí; lit. 'business') to build the colonial infrastructure in the islands. Many Chinese immigrants converted to Christianity, intermarried with the locals, and adopted Hispanized names and customs and became assimilated, although the children of unions between Filipinos and Chinese that became assimilated continued to be designated in official records as mestizos de sangley. The Chinese mestizos were largely confined to the Binondo area until the 19th century. However, they eventually spread all over the islands and became traders, landowners and moneylenders. Today, their descendants still comprise a significant part of the Philippine population especially its bourgeois,[129] who during the late Spanish Colonial Era in the late 19th century, produced a major part of the ilustrado intelligentsia of the late Spanish Colonial Philippines, that were very influential with the creation of Filipino nationalism and the sparking of the Philippine Revolution as part of the foundation of the First Philippine Republic and subsequent sovereign independent Philippines.[130][131] Today, the bulk of the families in the list of the political families in the Philippines have such family background. Meanwhile, the colonial-era Sangley's pure ethnic Chinese descendants of which, replenished by later migrants in the 20th century, that preserved at least some of their Chinese culture, integrated together with mainstream Filipino culture, are now in the form of the modern Chinese Filipino community, who currently play a leading role in the Philippine business sector and contribute a significant share of the Philippine economy today,[132][133][134][135][136] where most in the current list of the Philippines' richest each year comprise Taipan billionaires of Chinese Filipino background, mostly of Hokkien descent, where most still trace their roots back to mostly Jinjiang or Nan'an within Quanzhou or sometimes Xiamen (Amoy) or Zhangzhou, all within Southern Fujian, the Philippines' historical trade partner with Mainland China.

In the 16th and 17th centuries, thousands of Japanese traders also migrated to the Philippines and assimilated into the local population.[137][failed verification] Many were assimilated throughout the centuries, especially through the tumultuous period of World War II. Today, there is a small growing Nikkei community of Japanese Filipinos in Davao with roots to the old Little Japan in Mintal or Calinan in Davao City during the American colonial period, where many had roots starting out in Abaca plantations or from workers of the Benguet Road (Kennon Road) to Baguio.

British forces occupied Manila between 1762 and 1764 as a part of the Seven Years' War. However, the only part of the Philippines which the British held was the Spanish colonial capital of Manila and the principal naval port of Cavite, both of which are located on Manila Bay. The war was ended by the Treaty of Paris (1763). At the end of the war the treaty signatories were not aware that Manila had been taken by the British and was being administered as a British colony. Consequently, no specific provision was made for the Philippines. Instead they fell under the general provision that all other lands not otherwise provided for be returned to the Spanish Empire.[138] Many Indian Sepoy troops and their British captains mutinied and were left in Manila and some parts of the Ilocos and Cagayan. The Indian Filipinos in Manila settled at Cainta, Rizal and the ones in the north settled in Isabela. Most were assimilated into the local population. Even before the British invasion, there were already also a large but unknown number of Indian Filipinos as majority of the slaves imported into the archipelago were from Bengal or Southern India,[139] adding Dravidian speaking South Indians and Indo-European speaking Bangladeshis into the ethnic mix.

A total of 110 Manila-Acapulco galleons set sail between 1565 and 1815, during the Philippines trade with Mexico. Until 1593, three or more ships would set sail annually from each port bringing with them the riches of the archipelago to Spain. European criollos, mestizos and Portuguese, French and Mexican descent from the Americas, mostly from Latin America came in contact with the Filipinos. Japanese, Indian and Cambodian Christians who fled from religious persecutions and killing fields also settled in the Philippines during the 17th until the 19th centuries. The Mexicans especially were a major source of military migration to the Philippines and during the Spanish period they were referred to as guachinangos[140][141] and they readily intermarried and mixed with native Filipinos. Bernal, the author of the book "Mexico en Filipinas" contends, that they were middlemen, the guachinangos in contrast to the Spanish and criollos, known as Castila, that had positions in power and were isolated, the guachinangos in the meantime, had interacted with the natives of the Philippines, while in contrast, the exchanges between Castila and native were negligent. Following Bernal, these two groups—native Filipinos and the Castila—had been two "mutually unfamiliar castes" that had "no real contact." Between them, he clarifies however, were the Chinese traders and the guachinangos (Mexicans).[140] In the 1600s, Spain deployed thousands of Mexican and Peruvian soldiers across the many cities and presidios of the Philippines.[142]

| Location | 1603 | 1636 | 1642 | 1644 | 1654 | 1655 | 1670 | 1672 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manila[142] | 900 | 446 | — | 407 | 821 | 799 | 708 | 667 |

| Fort Santiago[142] | — | 22 | — | — | 50 | — | 86 | 81 |

| Cavite[142] | — | 70 | — | — | 89 | — | 225 | 211 |

| Cagayan[142] | 46 | 80 | — | — | — | — | 155 | 155 |

| Calamianes[142] | — | — | — | — | — | — | 73 | 73 |

| Caraga[142] | — | 45 | — | — | — | — | 81 | 81 |

| Cebu[142] | 86 | 50 | — | — | — | — | 135 | 135 |

| Formosa[142] | — | 180 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Moluccas[142] | 80 | 480 | 507 | — | 389 | — | — | — |

| Otón[142] | 66 | 50 | — | — | — | — | 169 | 169 |

| Zamboanga[142] | — | 210 | — | — | 184 | — | — | — |

| Other[142] | 255 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| [142] | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Total Reinforcements[142] | 1,533 | 1,633 | 2,067 | 2,085 | n/a | n/a | 1,632 | 1,572 |

With the inauguration of the Suez Canal in 1867, Spain opened the Philippines for international trade. European investors such as British, Dutch, German, Portuguese, Russian, Italian and French were among those who settled in the islands as business increased. More Spaniards and Chinese arrived during the next century. Many of these migrants intermarried with local mestizos and assimilated with the indigenous population.

In the late 1700s to early 1800s, Joaquín Martínez de Zúñiga, an Agustinian Friar, in his Two Volume Book: "Estadismo de las islas Filipinas"[143][144] compiled a census of the Spanish-Philippines based on the tribute counts (Which represented an average family of seven to ten children[145] and two parents, per tribute)[146] and came upon the following statistics:[143]: 539 [144]: 31, 54, 113

| Province | Native Tributes | Spanish Mestizo Tributes | All Tributes[a] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tondo[143]: 539 | 14,437-1/2 | 3,528 | 27,897-7 |

| Cavite[143]: 539 | 5,724-1/2 | 859 | 9,132-4 |

| Laguna[143]: 539 | 14,392-1/2 | 336 | 19,448-6 |

| Batangas[143]: 539 | 15,014 | 451 | 21,579-7 |

| Mindoro[143]: 539 | 3,165 | 3-1/2 | 4,000-8 |

| Bulacan[143]: 539 | 16,586-1/2 | 2,007 | 25,760-5 |

| Pampanga[143]: 539 | 16,604-1/2 | 2,641 | 27,358-1 |

| Bataan[143]: 539 | 3,082 | 619 | 5,433 |

| Zambales[143]: 539 | 1,136 | 73 | 4,389 |

| Ilocos[144]: 31 | 44,852-1/2 | 631 | 68,856 |

| Pangasinan[144]: 31 | 19,836 | 719-1/2 | 25,366 |

| Cagayan[144]: 31 | 9,888 | 0 | 11,244-6 |

| Camarines[144]: 54 | 19,686-1/2 | 154-1/2 | 24,994 |

| Albay[144]: 54 | 12,339 | 146 | 16,093 |

| Tayabas[144]: 54 | 7,396 | 12 | 9,228 |

| Cebu[144]: 113 | 28,112-1/2 | 625 | 28,863 |

| Samar[144]: 113 | 3,042 | 103 | 4,060 |

| Leyte[144]: 113 | 7,678 | 37-1/2 | 10,011 |

| Caraga[144]: 113 | 3,497 | 0 | 4,977 |

| Misamis[144]: 113 | 1,278 | 0 | 1,674 |

| Negros Island[144]: 113 | 5,741 | 0 | 7,176 |

| Iloilo[144]: 113 | 29,723 | 166 | 37,760 |

| Capiz[144]: 113 | 11,459 | 89 | 14,867 |

| Antique[144]: 113 | 9,228 | 0 | 11,620 |

| Calamianes[144]: 113 | 2,289 | 0 | 3,161 |

| TOTAL | 299,049 | 13,201 | 424,992-16 |

The Spanish-Filipino population as a proportion of the provinces widely varied; with as high as 19% of the population of Tondo province [143]: 539 (The most populous province and former name of Manila), to Pampanga 13.7%,[143]: 539 Cavite at 13%,[143]: 539 Laguna 2.28%,[143]: 539 Batangas 3%,[143]: 539 Bulacan 10.79%,[143]: 539 Bataan 16.72%,[143]: 539 Ilocos 1.38%,[144]: 31 Pangasinan 3.49%,[144]: 31 Albay 1.16%,[144]: 54 Cebu 2.17%,[144]: 113 Samar 3.27%,[144]: 113 Iloilo 1%,[144]: 113 Capiz 1%,[144]: 113 Bicol 20%,[147] and Zamboanga 40%.[147] Across the whole Philippines, as estimated, the total ratio of Spanish Filipino tributes amount to 5% of the totality.[143][144]

In the 1860s to 1890s, in the urban areas of the Philippines, especially at Manila, according to burial statistics, as much as 3.3% of the population were pure European Spaniards and the pure Chinese were as high as 9.9%. The Spanish Filipino and Chinese Filipino Mestizo populations also fluctuated. Eventually, many families belonging to the non-native categories from centuries ago beyond the late 19th century diminished because their descendants intermarried enough and were assimilated into and chose to self-identify as Filipinos while forgetting their ancestor's roots[148] since during the Philippine Revolution to modern times, the term "Filipino" was expanded to include everyone born in the Philippines coming from any race, as per the Philippine nationality law.[149][150] That would explain the abrupt drop of otherwise high Chinese, Spanish and mestizo, percentages across the country by the time of the first American census in 1903.[151] By the 20th century, the remaining ethnic Spaniards and ethnic Chinese, replenished by further Chinese migrants in the 20th century, now later came to compose the modern Spanish Filipino community and Chinese Filipino community respectively, where families of such background contribute a significant share of the Philippine economy today,[132][133][3][135][136] where most in the current list of the Philippines' richest each year comprise billionaires of either Chinese Filipino background or the old elite families of Spanish Filipino background.

Late modern

After the defeat of Spain during the Spanish–American War in 1898, Filipino general, Emilio Aguinaldo declared independence on June 12 while General Wesley Merritt became the first American governor of the Philippines. On December 10, 1898, the Treaty of Paris formally ended the war, with Spain ceding the Philippines and other colonies to the United States in exchange for $20 million.[152]

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Manilamen

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk