A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

Manila

Maynila | |

|---|---|

| City of Manila | |

|

| |

| Nickname(s): | |

| Motto(s): Manila, God First Welcome Po Kayo sa Maynila (transl. You are welcome in Manila) | |

| Anthem: Awit ng Maynila (Song of Manila) | |

Map of Metro Manila with Manila highlighted[a] | |

Location within the Philippines | |

| Coordinates: 14°35′45″N 120°58′38″E / 14.5958°N 120.9772°E | |

| Country | |

| Region | National Capital Region |

| Legislative district | 1st to 6th district |

| Administrative district | 16 city districts |

| Established | 13th century or earlier |

| Sultanate of Brunei (Rajahnate of Maynila) | 1500s |

| Spanish Manila | June 24, 1571 |

| City charter | July 31, 1901 |

| Highly urbanized city | December 22, 1979 |

| Barangays | 897 (see Barangays and districts) |

| Government | |

| • Type | Sangguniang Panlungsod |

| • Mayor | Honey Lacuna (Aksyon/Asenso Manileño) |

| • Vice Mayor | Yul Servo (Aksyon/Asenso Manileño) |

| • Representatives | |

| • City Council | List |

| • Electorate | 1,133,042 voters (2022) |

| Area | |

| • City | 42.34 km2 (16.35 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 1,873 km2 (723 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 619.57 km2 (239.22 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 7.0 m (23.0 ft) |

| Highest elevation | 108 m (354 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Population | |

| • City | 1,846,513 |

| • Density | 43,611.5/km2 (112,953/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 13,484,482[4] |

| • Urban density | 21,764.3/km2 (56,369/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 24,922,000 |

| • Metro density | 13,305.9/km2 (34,462/sq mi) |

| • Households | 486,293 |

| Demonym(s) | English: Manileño, Manilan; Spanish: manilense,[7] manileño(-a) Filipino: Manileño(-a), Manilenyo(-a), Taga-Maynila |

| Economy | |

| • Income class | special city income class |

| • Poverty incidence | 1.10 |

| • HDI | |

| • Revenue | ₱ 17,923 million (2020) |

| • Assets | ₱ 74,465 million (2020) |

| • Expenditure | ₱ 17,875 million (2020) |

| • Liabilities | ₱ 22,421 million (2020) |

| Utilities | |

| • Electricity | Manila Electric Company (Meralco) |

| • Water | • Maynilad (Majority) • Manila Water (Santa Ana and San Andres) |

| Time zone | UTC+8 (PST) |

| ZIP code | +900 – 1-096 |

| PSGC | |

| IDD : area code | +63 (0)2 |

| Native languages | Tagalog |

| Currency | Philippine peso (₱) |

| Website | manila |

| |

Manila (/məˈnɪlə/ mə-NIL-ə; Filipino: Maynila, pronounced [majˈnilaʔ]), officially the City of Manila (Filipino: Lungsod ng Maynila, [luŋˈsod nɐŋ majˈnilaʔ]), is the capital and second-most-populous city of the Philippines. Located on the eastern shore of Manila Bay on the island of Luzon, it is classified as a highly urbanized city. As of 2019, it is the world's most densely populated city proper. It was the first chartered city in the country, and was designated as such by the Philippine Commission Act No. 183 on July 31, 1901. It became autonomous with the passage of Republic Act No. 409, "The Revised Charter of the City of Manila", on June 18, 1949.[10] Manila is considered to be part of the world's original set of global cities because its commercial networks were the first to extend across the Pacific Ocean and connect Asia with the Spanish Americas through the galleon trade; when this was accomplished, it was the first time an uninterrupted chain of trade routes circling the planet had been established.[11][12]

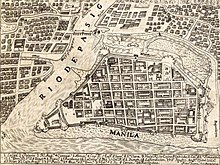

By 1258, a Tagalog-fortified polity called Maynila existed on the site of modern Manila. On June 24, 1571, after the defeat of the polity's last indigenous Rajah Sulayman in the Battle of Bangkusay, Spanish conquistador Miguel López de Legazpi began constructing the walled fortification Intramuros on the ruins of an older settlement from whose name the Spanish-and-English name Manila derives. Manila was used as the capital of the captaincy general of the Spanish East Indies, which included the Marianas, Guam and other islands, and was controlled and administered for the Spanish crown by Mexico City in the Viceroyalty of New Spain.

In modern times, the name "Manila" is commonly used to refer to the whole metropolitan area, the greater metropolitan area, and the city proper. Metro Manila, the officially defined metropolitan area, is the capital region of the Philippines, and includes the much-larger Quezon City and the Makati Central Business District. It is the most-populous region in the country, one of the most-populous urban areas in the world,[13] and one of the wealthiest regions in Southeast Asia. The city proper was home to 1,846,513 people in 2020,[5] and is the historic core of a built-up area that extends well beyond its administrative limits. With 71,263 inhabitants per square kilometer (184,570/sq mi), Manila is the most densely populated city proper in the world.[5][6]

The Pasig River flows through the middle of the city, dividing it into north and south sections. The city comprises 16 administrative districts and is divided into six political districts for the purposes of representation in the Congress of the Philippines and the election of city council members. In 2018, the Globalization and World Cities Research Network listed Manila as an "Alpha-" global city,[14] and ranked it seventh in economic performance globally and second regionally,[15] while the Global Financial Centres Index ranks Manila 79th in the world.[16] Manila is also the world's second-most natural disaster exposed city,[17] yet is also among the fastest developing cities in Southeast Asia.[18]

Etymology

Maynilà, the Filipino name for the city, comes from the phrase may-nilà, meaning "where indigo is found".[19] Nilà is derived from the Sanskrit word nīla (नील), which refers to indigo dye and, by extension, to several plant species from which this natural dye can be extracted.[19][20] The name Maynilà was probably bestowed because of the indigo-yielding plants that grow in the area surrounding the settlement rather than because it was known as a settlement that traded in indigo dye.[19] Indigo dye extraction only became an important economic activity in the area in the 18th century, several hundred years after Maynila settlement was founded and named.[19] Maynilà eventually underwent a process of Hispanicization and adopted the Spanish name Manila.[21]

May-nilad

According to an antiquated, inaccurate, and now debunked etymological theory, the city's name originated from the word may-nilad (meaning "where nilad is found").[19] There are two versions of this false etymology. One popular incorrect notion is that the old word nilad refers to the water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes) that grows on the banks of the Pasig River.[19] This plant species, however, was only recently introduced into the Philippines from South America and therefore could not be the source of the toponym for old Manila.[19]

Another incorrect etymology arose from the observation that, in Tagalog, nilád or nilár refers to a shrub-like tree (Scyphiphora hydrophyllacea; formerly Ixora manila Blanco) that grows in or near mangrove swamps.[19][22][23] Linguistic analysis, however, shows the word Maynilà is unlikely to have developed from this term. It is unlikely native Tagalog speakers would completely drop the final consonant /d/ in nilad to arrive at the present form Maynilà.[19] As an example, nearby Bacoor retains the final consonant of the old Tagalog word bakoód ("elevated piece of land"), even in old Spanish renderings of the placename (e.g., Vacol, Bacor).[24] Historians Ambeth Ocampo[25][26] and Joseph Baumgartner[19] have shown, in every early document, that the place name Maynilà was always written without a final /d/. This documentation shows that the may-nilad etymology is spurious.

Originally, the mistaken identification of nilad as the source of the toponym probably originated in an 1887 essay by Trinidad Pardo de Tavera, in which he mistakenly used the word nila to refer both to Indigofera tinctoria (true indigo) and to Ixora manila, which is actually nilád in Tagalog.[23]).[20][19] Early 20th century writings, such as those of Julio Nakpil,[27] and Blair and Robertson, repeated the claim.[28][26] Today, this erroneous etymology continues to be perpetuated through casual repetition in literature[29][30] and in popular use. Examples of popular adoption of this mistaken etymology include the name of a local utility company Maynilad Water Services and the name of an underpass close to Manila City Hall, Lagusnilad (meaning "Nilad Pass").[25]

On the other hand, in a rather first account of importance on the Philippine flora that appeared in 1704 as an Appendix to Ray's Historia Plantarum which is the Herbarium aliarumque Stirpium in Insula Luzone Philippinarum primaria nascentium... by Fr. Georg Josef Kamel[31], he mentioned that, Nilad arbor mediocris, rarissimi recta, ligno folido, et compacto ut Molavin, ubi abundant Mangle, locum vocant Manglar, ita ubi nilad, Maynilad, unde corrupte Manila (Nilad is an average tree, very rare straight, leafy wood, and compact like Molavin, where Mangle abounds, the place is called Manglar, so where nilad (abounds), Maynilad, whence the corruption Manila)[32], making this an earlier account of the change in this name.

History

Early history

| Battles of Manila |

|---|

| See also |

|

| Around Manila |

|

The earliest evidence of human life around present-day Manila is the nearby Angono Petroglyphs, which are dated to around 3000 BC. Negritos, the aboriginal inhabitants of the Philippines, lived across the island of Luzon, where Manila is located, before Malayo-Polynesians arrived and assimilated them.[33]

Manila was an active trade partner with the Song and Yuan dynasties of China.[34]

The polity of Tondo flourished during the latter half of the Ming dynasty as a result of direct trade relations with China. Tondo district was the traditional capital of the empire and its rulers were sovereign kings rather than chieftains. Tondo was named using traditional Chinese characters in the Hokkien reading, Chinese: 東都; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Tong-to͘; lit. 'Eastern Capital', due to its chief position southeast of China. The kings of Tondo were addressed as panginoón in Tagalog ("lords"); anák banwa ("son of heaven"); or lakandula ("lord of the palace"). The Emperor of China considered the lakans—the rulers of ancient Manila—"王" (kings).[35]

During the 12th century, then-Hindu Brunei called "Pon-i", as reported in the Chinese annals Nanhai zhi, invaded Malilu 麻裏蘆 (present-day Manila) as it also administered Sarawak and Sabah, as well as the Philippine kingdoms Butuan, Sulu, Ma-i (Mindoro), Shahuchong 沙胡重 (present-day Siocon), Yachen 啞陳 (Oton), and 文杜陵 Wenduling (present-day Mindanao). Manila regained independence.[36] In the 13th century, Manila consisted of a fortified settlement and trading quarter on the shore of the Pasig River. It was then settled by the Indianized empire of Majapahit, according to the epic eulogy poem Nagarakretagama, which described the area's conquest by Maharaja Hayam Wuruk. Selurong (षेलुरोङ्), a historical name for Manila, is listed in Canto 14 alongside Sulot – which is now Sulu – and Kalka. Selurong, together with Sulot, was able to regain independence afterward, and Sulu attacked and looted the then-Majapahit-invaded province Po-ni (Brunei) in retribution.[37]

During the reign of the Arab emir, Sultan Bolkiah – Sharif Ali's descendant – from 1485 to 1521, the Sultanate of Brunei which had seceded from Hindu Majapahit and converted to Islam, had invaded the area. The Bruneians wanted to take advantage of Tondo's strategic position in direct trade with China and subsequently attacked the region and established the rajahnate of Maynilà (كوتا سلودوڠ; Kota Seludong). The rajahnate was ruled under Brunei and gave yearly tribute as a satellite state.[38] It created a new dynasty under the local leader, who accepted Islam and became Rajah Salalila or Sulaiman I. He established a trading challenge to the already rich House of Lakan Dula in Tondo. Islam was further strengthened by the arrival of Muslim traders from the Middle East and Southeast Asia.[39]

Spanish colonial era

On June 24, 1571, conquistador Miguel López de Legazpi arrived in Manila and declared it a territory of New Spain (Mexico), establishing a city council in what is now Intramuros district. Inspired by the Reconquista, a war in mainland Spain to re-Christianize and reclaim parts of the country that had been ruled by the Umayyad Caliphate, he took advantage of a territorial conflict between Hindu Tondo and Islamic Manila to justify expelling or converting Bruneian Muslim colonists who supported their Manila vassals while his Mexican grandson Juan de Salcedo had a romantic relationship with Kandarapa, a princess of Tondo.[40] López de Legazpi had the local royalty executed or exiled after the failure of the Conspiracy of the Maharlikas, a plot in which an alliance of datus, rajahs, Japanese merchants, and the Sultanate of Brunei would band together to execute the Spaniards, along with their Latin American recruits and Visayan allies. The victorious Spaniards made Manila the capital of the Spanish East Indies and of the Philippines, which their empire would control for the next three centuries. In 1574, Manila was besieged by the Chinese pirate Lim Hong, who was thwarted by local inhabitants. Upon Spanish settlement, Manila was immediately made, by papal decree, a suffragan of the Archdiocese of Mexico. By royal decree of Philip II of Spain, Manila was put under the spiritual patronage of Saint Pudentiana and Our Lady of Guidance.[a]

Manila became famous for its role in the Manila–Acapulco galleon trade, which lasted for more than two centuries and brought goods from Europe, Africa, and Hispanic America across the Pacific Islands to Southeast Asia, and vice versa. Silver that was mined in Mexico and Peru was exchanged for Chinese silk, Indian gems, and spices from Indonesia and Malaysia. Wine and olives grown in Europe and North Africa were shipped via Mexico to Manila.[41] Because of the Ming ban on trade leveled against the Ashikaga shogunate in 1549, this resulted in the ban of all Japanese people from entering China and of Chinese ships from sailing to Japan. Manila became the only place where the Japanese and Chinese could openly trade.[42] In 1606, upon the Spanish conquest of the Sultanate of Ternate, one of monopolizers of the growing of spice, the Spanish deported the ruler Sultan Said Din Burkat[43] of Ternate, along with his clan and his entourage to Manila, were they were initially enslaved and eventually converted to Christianity.[44] About 200 families of mixed Spanish-Mexican-Filipino and Moluccan-Indonesian-Portuguese descent from Ternate and Tidor followed him there at a later date.[45]

The city attained great wealth due to its location at the confluence of the Silk Road, the Spice Route, and the Silver Way.[46] Significant is the role of Armenians, who acted as merchant intermediaries that made trade between Europe and Asia possible in this area. France was the first nation to try financing its Asian trade with a partnership in Manila through Armenian khojas. The largest trade volume was in iron, and 1,000 iron bars were traded in 1721.[47] In 1762, the city was captured by Great Britain as part of the Seven Years' War, in which Spain had recently become involved.[48] The British occupied the city for twenty months from 1762 to 1764 in their attempt to capture the Spanish East Indies but they were unable to extend their occupation past Manila proper.[49] Frustrated by their inability to take the rest of the archipelago, the British withdrew in accordance with the Treaty of Paris signed in 1763, which brought an end to the war. An unknown number of Indian soldiers known as sepoys, who came with the British, deserted and settled in nearby Cainta, Rizal.[50][51]

The Chinese minority were punished for supporting the British, and the fortress city Intramuros, which was initially populated by 1,200 Spanish families and garrisoned by 400 Spanish troops,[52] kept its cannons pointed at Binondo, the world's oldest Chinatown.[53] The population of native Mexicans was concentrated in the southern part of Manila and in 1787, La Pérouse recorded one regiment of 1,300 Mexicans garrisoned at Manila,[54] and they were also at Cavite, where ships from Spain's American colonies docked at,[55] and at Ermita, which was thus-named because of a Mexican hermit who lived there. The Hermit-Priest's name was Juan Fernandez de Leon who was a Hermit in Mexico before relocating to Manila.[56] Priests weren't usually alone too since they often brought along Lay Brothers and Sisters. The years: 1603, 1636, 1644, 1654, 1655, 1670, and 1672; saw the deployment of 900, 446, 407, 821, 799, 708, and 667 Latin-American soldiers from Mexico at Manila.[57] The Philippines hosts the only Latin-American-established districts in Asia.[58] The Spanish evacuated Ternate and settled Papuan refugees in Ternate, Cavite, which was named after their former homeland.[59]

The rise of Spanish Manila marked the first time all hemispheres and continents were interconnected in a worldwide trade network, making Manila, alongside Mexico City and Madrid, the world's original set of global cities.[60] A Spanish Jesuit priest commented due to the confluence of many foreign languages in Manila, the confessional in Manila was "the most difficult in the world".[61][62] Juan de Cobo, another Spanish missionary of the 1600s, was so astonished by the commerce, cultural complexity, and ethnic diversity in Manila he wrote to his brethren in Mexico:

The diversity here is immense such that I could go on forever trying to differentiate lands and peoples. There are Castilians from all provinces. There are Portuguese and Italians; Dutch, Greeks and Canary Islanders, and Mexican Indians. There are slaves from Africa brought by the Spaniards , and others brought by the Portuguese . There is an African Moor with his turban here. There are Javanese from Java, Japanese and Bengalese from Bengal. Among all these people are the Chinese whose numbers here are untold and who outnumber everyone else. From China there are peoples so different from each other, and from provinces as distant, as Italy is from Spain. Finally, of the mestizos, the mixed-race people here, I cannot even write because in Manila there is no limit to combinations of peoples with peoples. This is in the city where all the buzz is. (Remesal, 1629: 680–1)[63]

After Mexico gained independence from Spain in 1821, the Spanish crown began to directly govern Manila.[64] Under direct Spanish rule, banking, industry, and education flourished more than they had in the previous two centuries.[65] The opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 facilitated direct trade and communications with Spain. The city's growing wealth and education attracted indigenous peoples, Negritos, Malays, Africans, Chinese, Indians, Arabs, Europeans, Latinos and Papuans from the surrounding provinces,[66] and facilitated the rise of an ilustrado class who espoused liberal ideas, which became the ideological foundations of the Philippine Revolution, which sought independence from Spain. A revolt by Andres Novales was inspired by the Latin American wars of independence but the revolt itself was led by demoted Latin-American military officers stationed in the city from the newly independent nations of Mexico, Colombia, Venezuela, Peru, Chile, Argentina, and Costa Rica.[67] Following the Cavite Mutiny and the Propaganda Movement, the Philippine revolution began; Manila was among the first eight provinces to rebel and their role was commemorated on the Philippine Flag, on which Manila was represented by one of the eight rays of the symbolic sun.[68]

American invasion era

After the 1898 Battle of Manila, Spain ceded the city to the United States. The First Philippine Republic based in nearby Bulacan fought against the Americans for control of the city.[69] The Americans defeated the First Philippine Republic and captured its president Emilio Aguinaldo, who pledged allegiance to the U.S. on April 1, 1901.[70] Upon drafting a new charter for Manila in June 1901, the U.S. officially recognized the city of Manila consisted of Intramuros and the surrounding areas. The new charter proclaimed Manila was composed of eleven municipal districts: Binondo, Ermita, Intramuros, Malate, Paco, Pandacan, Sampaloc, San Miguel, Santa Ana, Santa Cruz, and Tondo. The Catholic Church recognized five parishes as parts of Manila; Gagalangin, Trozo, Balic-Balic, Santa Mesa, and Singalong; and Balut and San Andres were later added.[71]

Under U.S. control, a new, civilian-oriented Insular Government headed by Governor-General William Howard Taft invited city planner Daniel Burnham to adapt Manila to modern needs.[72] The Burnham Plan included the development of a road system, the use of waterways for transportation, and the beautification of Manila with waterfront improvements and construction of parks, parkways, and buildings.[73][74] The planned buildings included a government center occupying all of Wallace Field, which extends from Rizal Park to the present Taft Avenue. The Philippine capitol was to rise at the Taft Avenue end of the field, facing the sea. Along with buildings for government bureaus and departments, it would form a quadrangle with a central lagoon and a monument to José Rizal at the other end of the field.[75] Of Burnham's proposed government center, only three units—the Legislative Building, and the buildings of the Finance and Agricultural Departments—were completed before World War II began.

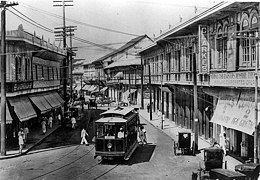

- Gallery of Manila during the American era

-

Plaza Moraga in the early 1900s

-

The Old Legislative Building featuring a Neoclassical style architecture.

-

Aerial view of Manila, 1936

Japanese occupation era

During the Japanese occupation of the Philippines, American soldiers were ordered to withdraw from Manila and all military installations were removed by December 24, 1941. Two days later, General Douglas MacArthur declared Manila an open city to prevent further death and destruction but Japanese warplanes continued bombing the city.[76] Japanese forces occupied Manila on January 2, 1942.[77]

From February 3 to March 3, 1945, Manila was the site of one of the bloodiest battles in the Pacific theater of World War II. Under orders of Japanese Rear Admiral Sanji Iwabuchi, retreating Japanese forces killed about 100,000 Filipino civilians and perpetrated the mass rape of women in February.[78][79] At the end of the war, Manila had suffered from heavy bombardment and became the second-most-destroyed city of World War II.[80][81] Manila was recaptured by American and Philippine troops.

The postwar and independence era

After the war, reconstruction efforts started. Buildings like Manila City Hall, the Legislative Building (now the National Museum of Fine Arts), and Manila Post Office were rebuilt, and roads and other infrastructures were repaired. In 1948, President Elpidio Quirino moved the seat of government of the Philippines to Quezon City, a new capital in the suburbs and fields northeast of Manila, which was created in 1939 during the administration of President Manuel L. Quezon.[82] The move ended any implementation of the Burnham Plan's intent for the government center to be at Luneta. When Arsenio Lacson became the first elected Mayor of Manila in 1952, before which all mayors were appointed, Manila underwent a "Golden Age",[83] regaining its pre-war moniker "Pearl of the Orient". After Lacson's term in the 1950s, Manila was led by Antonio Villegas for most of the 1960s. Ramon Bagatsing was mayor from 1972 until the 1986 People Power Revolution.[84]

During the administration of Ferdinand Marcos, Metro Manila was created as an integrated unit with the enactment of Presidential Decree No. 824 on November 7, 1975. The area encompassed four cities and thirteen adjoining towns as a separate regional unit of government.[85] On June 24, 1976, the 405th anniversary of the city's founding, President Marcos reinstated Manila as the capital of the Philippines for its historical significance as the seat of government since the Spanish Period.[86][87] At the same time, Marcos designated his wife Imelda Marcos as the first governor of Metro Manila. She started the rejuvenation of the city and re-branded Manila the "City of Man".[88]

The Martial Law era

Many of the key events of he historical period from the first major protests against the administration of Ferdinand Marcos in January 1970 until his ouster in February 1986 took place within the city of Manila. The first, the January 26, 1970, State of the Nation Address Protest which kicked off the "First Quarter Storm", took place at the Legislative Building (now the National Museum of Fine Arts) on Padre Burgos Avenue,[89] and the very last saw the Marcos family flee Malacañang Palace into exile in the United States.[90][91][92]

The beginning weeks of Ferdinand Marcos' second term as president was marked by the 1969 balance of payments crisis, which economists trace to his first term tactic of using foreign loans to fund massive government projects in an effort to curry votes.[93][94][95] In protest, protest groups led mostly by students decided to picket Marcos' 1970 State of the Nation Address at the legislative building on January 26. The protesters were initially bickering amongst themselves because both moderate reformist and radical activist groups were present and fighting to gain control of the stage. But all of them, regardless of advocacy, were violently dispersed by the Philippine Constabulary.[96][97] This was followed by six more major protests which were violently dispersed, from the end of January until March 17, 1970.[91]

Instability continued the following year, with the most significant incident being the August 1971 Plaza Miranda bombing caused nine deaths and injured 95 others, including many prominent Liberal Party politicians including incumbent Senators Jovito Salonga, Eddie Ilarde, Eva Estrada-Kalaw, and Liberal Party president Gerardo Roxas, Sergio Osmeña Jr., Manila 2nd District Councilor Ambrosio "King" Lorenzo Jr., and Congressman Ramon Bagatsing who was the party's mayoral candidate for Manila.[97]

Marcos reacted to the bombing by blaming the still nascent Communist Party of the Philippines and then suspending of the writ of Habeas Corpus. The suspension is noted for forcing many members of the moderate opposition, including figures like Edgar Jopson, to join the ranks of the radicals. In the aftermath of the bombing, Marcos lumped all of the opposition together and referred to them as communists, and many former moderates fled to the mountain encampments of the radical opposition to avoid being arrested by Marcos' forces. Those who became disenchanted with the excesses of the Marcos administration and wanted to join the opposition after 1971 often joined the ranks of the radicals, simply because they represented the only group vocally offering opposition to the Marcos government.[98][99]

Marcos' declaration of martial law in September 1972 saw the immediate shutdown of all media not approved by Marcos, including Quezon City media outlets, including the Manila-based Manila Times, Philippines Free Press, The Manila Tribune and the Philippines Herald. At the same time, it saw the arrest of many students, journalists, academics, and politicians who were considered political threats to Marcos, many of them residents of the City of Manila. The first one was Ninoy Aquino who was arrested just before midnight on September 22 while at a hotel on UN Avenue preparing for a senate committee session the following morning.[97]

About 400 prominent critics of the Marcos administration were jailed in the first few hours of September 23 alone, and eventually about 70,000 individuals beame Political detainees under the Marcos dictatorship - most of them arrested without warrants, which is why they were called detainees rather than prisoners.[100][101] At least 11,103 of them have since been officially recognized by the Philippine government as having been extensively tortured and abused.[102][103] and in April 1973 Pamantasan ng Lungsod ng Maynila student journalist Liliosa Hilao became the first of these detainees to be killed while in prison[104] - one of 3,257 known extrajudicial killings during the last 14 years of Marcos' presidency.[105]

In 1975, Marcos formalized the creation of a region called Metropolitan Manila, incorporating the four cities of Manila, Quezon City, Caloocan, Pasay, and the thirteen municipalities of Las Piñas, Makati, Malabon, Mandaluyong, Marikina, Muntinlupa, Navotas, Parañaque, Pasig, Pateros, San Juan, Taguig, and Valenzuela. And then he appointed his wife Imelda Marcos, who had been angered by the revelation of his dalliances during the Dovie Beams scandal, Governor of Metro Manila.[106]

Despite Marcos' declaration of martial law, poverty and other social issues persisted, so even with the military in his control, Marcos could not hold back the unrest. A major turning point was reached in Tondo in the form of the 1975 La Tondeña Distillery strike which was one of the first major open acts of resistance against the Marcos dictatorship which paved the way for similar protest actions elsewhere in the country.[107] From then, Manila continued to be a center of resistance activity; youth and student demonstrators repeatedly clashed with the police and military.[108]

Another major protest was the September 1984 Welcome Rotonda protest dispersal at the border of Manila and Quezon City, which came in the wake of the Aquino assassination the year before in 1983. International pressure had forced Marcos to give the press more freedom, so coverage exposed Filipinos to how opposition figures including 80-year-old former Senator Lorenzo Tañada and 71-year old Manila Times founder Chino Roces were waterhosed despite their frailty and how student leader Fidel Nemenzo (later Chancellor of the University of the Philippines Diliman) was shot nearly to death.[109][110][111]

The People Power revolution

In late 1985, in the face of escalating public discontent and under pressure from foreign allies, Marcos called a snap election with more than a year left in his term, selecting Arturo Tolentino as his running mate. The opposition to Marcos united behind Ninoy's widow Corazon Aquino and her running mate, Salvador Laurel.[112][113] The elections were held on February 7, 1986, an exercise marred by widespread reports of violence and tampering of election results.[114]

On February 16, 1986, Corazon Aquino held the "Tagumpay ng Bayan" (People's Victory) rally at Luneta Park, announcing a civil disobedience campaign and calling for her supporters to boycott publications and companies which were associated with Marcos or any of his cronies.[115] The event was attended by a crowd of about two million people.[116] Aquino's camp began making preparations for more rallies, and Aquino herself went to Cebu to rally more people to their cause.[117]

In the aftermath of the election and the revelations of irregularities, Juan Ponce Enrile and the Reform the Armed Forces Movement (RAM) - a cabal of disgruntled officers of the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP)[118] - set into motion a coup attempt against the Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos.[119] Enrile and RAM's coup was quickly uncovered, and which prompted Enrile to ask for the support of Philippine Constabulary chief Fidel Ramos. Ramos agreed to Join Enrile but even so, their combined forces were trapped in Camp Crame and Camp Aguinaldo, and about to be overrun by Marcos loyalist forces.[120][121][122] Discovering what was happening, the forces which had been organizing Aquino's civil disobedience campaign went to the stretch of Efipanio De Los Santos Avenue (EDSA) between the two camps, beginning to form a human barricade to keep Marcos loyalist forces from attacking. The crowd grew even larger when Ramos telephoned Manila Cardinal Jaime Sin for help, and Sin went on Radyo Veritas to invite Catholics to join in protecting Enrile and Ramos.[123] Seeing what was happening, multiple units of the Armed Forces of the Philippines defected Marcos, with air units under the command of General Antonio Sotelo and Colonel Charles Hotchkiss even performed calculated operations which included strafing the grounds of Malacañang palace with bullets, and disabling gunships at nearby Villamor Airbase.[120]

The Reagan administration eventually decided to offer Marcos a chance to flee into exile. Shortly after midnight on February 26, 1986, the Marcos Family fled Malacañang and were taken to Clark Airbase, after which they went into exile in Honolulu along with some select followers including Fabian Ver and Danding Cojuangco.[90] Because the victory had been won by the civilians on the streets rather than the military, the event was dubbed the People Power revolution. Ferdinand Marcos' 21 years as President - and his 14 years as authoritarian leader - of the Philippines was over.[90][121]

Contemporary

From 1986 to 1992, Mel Lopez was mayor of Manila, first due to presidential designation, before being elected in 1988.[124] In 1992, Alfredo Lim was elected mayor, the first Chinese-Filipino to hold the office. He was known for his anti-crime crusades. Lim was succeeded by Lito Atienza, who served as his vice mayor, and was known for his campaign and slogun "Buhayin ang Maynila" (Revive Manila), which saw the establishment of several parks, and the repair and rehabilitation of the city's deteriorating facilities. He was the city's mayor for nine years before being termed out of office. Lim once again ran for mayor and defeated Atienza's son Ali in the 2007 city election, and immediately reversed all of Atienza's projects,[125] which he said made little contribution to the improvements of the city. The relationship of both parties turned bitter, with them both contesting the 2010 city elections, which Lim won. Lim was sued by councilor Dennis Alcoreza on 2008 over human rights,[126] he was charged with graft over the rehabilitation of public schools.[127]

In 2012, DMCI Homes began constructing Torre de Manila, which became controversial for ruining the sight line of Rizal Park.[128] The tower became known as "Terror de Manila" and the "national photobomber",[129] and became a sensationalized heritage issue. In 2017, the National Historical Commission of the Philippines erected a "comfort woman" statue on Roxas Boulevard, causing Japan to express regret about the statue's erection despite the healthy relationship between Japan and the Philippines.[130][131]

In the 2013 election, former President Joseph Estrada succeeded Lim as the city's mayor. During his term, Estrada allegedly paid ₱5 billion in city debts and increased the city's revenues. In 2015, in line with President Noynoy Aquino's administration progress, the city became the most-competitive city in the Philippines. In the 2016 elections, Estrada narrowly won over Lim.[132] Throughout Estrada's term, numerous Filipino heritage sites were demolished, gutted, or approved for demolition; these include the post-war Santa Cruz Building, Capitol Theater, El Hogar, Magnolia Ice Cream Plant, and Rizal Memorial Stadium.[133][134][135] Some of these sites were saved after the intervention of governmental cultural agencies and heritage advocate groups.[136] In May 2019, Estrada said Manila was debt-free;[137] two months later, however, the Commission on Audit said Manila was ₱4.4 billion in debt.[138]

Estrada, who was seeking for re-election for his third and final term, lost to Isko Moreno in the 2019 local elections.[139][140] Moreno has served as the vice mayor under both Lim and Estrada. Estrada's defeat was seen as the end of their reign as a political clan, whose other family members run for national and local positions.[141] After assuming office, Moreno initiated a city-wide cleanup of illegal vendors, signed an executive order promoting open governance, and vowed to stop bribery and corruption in the city.[142] Under his administration, several ordinances were signed, giving additional perks and privileges to Manila's elderly people,[143] and monthly allowances for Grade 12 Manileño students in all public schools in the city, including students of Universidad de Manila and the University of the City of Manila.[144][145]

In 2022, Time Out ranked Manila in 34th position in its list of the 53 best cities in the world, citing it as "an underrated hub for art and culture, with unique customs and cuisine to boot". Manila was also voted the third-most-resilient and least-rude city for the year's index.[146][147] In 2023, the search site Crossword Solm utilizing internet geotagging, showed that Manila is the world's most loving capital city.[148]

In August 2023, President Bongbong Marcos suspended all reclamation projects in Manila Bay, including those in the City of Manila.[149] However, the city has no objections and is willing to pursue the suspended reclamation projects.[150]

Geography

The City of Manila is situated on the eastern shore of Manila Bay, on the western coast of Luzon, 1,300 km (810 mi) from mainland Asia.[151] The protected harbor on which Manila lies is regarded as the finest in Asia.[152] The Pasig River flows through the middle of city, dividing it into north and south.[153][154] The overall grade of the city's central, built-up areas is relatively consistent with the natural flatness of the natural geography, generally exhibiting only slight differentiation.[155]

Almost all of Manila sits on top prehistoric alluvial deposits built by the waters of the Pasig River and on land reclaimed from Manila Bay. Manila's land has been substantially altered by human intervention; there has been considerable land reclamation along the waterfronts since the early-to-mid twentieth century. Some of the city's natural variations in topography have been leveled. As of 2013[update], Manila had a total area of 42.88 square kilometres (16.56 sq mi).[153][154]

In 2017, the City Government approved five reclamation projects; the New Manila Bay–City of Pearl (New Manila Bay International Community) (407.43 hectares (1,006.8 acres)), Solar City (148 hectares (370 acres)), Manila Harbour Center expansion (50 hectares (120 acres)), Manila Waterfront City (318 hectares (790 acres)),[156] and Horizon Manila (419 hectares (1,040 acres)). Of the five planned projects, only Horizon Manila was approved by the Philippine Reclamation Authority in December 2019 and was scheduled for construction in 2021.[157] Another reclamation project is possible and when built, it will include in-city housing relocation projects.[158] Environmental activists and the Catholic Church have criticized the land reclamation projects, saying they are not sustainable and would put communities at risk of flooding.[159][160] In line of the upcoming reclamation projects, the Philippines and the Netherlands agreed to a cooperation on the ₱250 million Manila Bay Sustainable Development Master Plan to oversee future decisions on projects on Manila Bay.[161]

Barangays and districts

Manila is made up of 897 barangays,[162] which are grouped into 100 zones for statistical convenience. Manila has the most barangays of any metropolis in the Philippines.[163] Due to a failure to hold a plebiscite, attempts at reducing its number have not succeeded despite local legislation—Ordinance 7907, passed on April 23, 1996—reducing the number from 896 to 150 by merging existing barangays.[164]

- District I (2020 population: 441,282)[165] covers the western part of Tondo and is made up of 136 barangays. It is the most-densely populated Congressional District and was also known as Tondo I. The district includes one of the biggest urban-poor communities. Smokey Mountain on Balut Island was once known as the country's largest landfill where thousands of impoverished people lived in slums. After the closure of the landfill in 1995, mid-rise housing was built on the site. This district also contains the Manila North Harbor Center, Manila North Harbor, and Manila International Container Terminal of the Port of Manila. The boundaries of the 1st District are the neighboring cities Navotas and the southern enclave of Caloocan.

- District II (2020 population: 212,938)[165] covers the eastern part of Tondo and contains 122 barangays. It is also referred to as Tondo II. It includes Gagalangin, a prominent place in Tondo, and Divisoria, a popular shopping area and the site of the Main Terminal Station of the Philippine National Railways. The boundary of the 2nd District is the neighboring city Caloocan.

- District III (2020 population: 220,029)[165] covers Binondo, Quiapo, San Nicolas and Santa Cruz. It contains 123 barangays and includes "Downtown Manila", the historic business district of the city, and the oldest Chinatown in the world. The boundary of the 3rd District is the neighboring city Quezon City.

- District IV (2020 population: 277,013)[165] covers Sampaloc and some parts of Santa Mesa. It contains 192 barangays and has numerous colleges and universities, which were located along the city's "University Belt", a de facto sub-district. The University of Santo Tomas, the oldest-existing university in Asia, which was established in 1611. The boundaries of the 4th District are the neighboring cities San Juan and Quezon City. The Institution was home to at least 30 Catholic Saints.[166][167]

- District V (2020 population: 395,065)[165] covers Ermita, Malate, Port Area, Intramuros, San Andres Bukid, and a portion of Paco. It is made up of 184 barangays. The historic Walled City is located here, along with Manila Cathedral and San Agustin Church, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The boundaries of the 5th District are the neighboring cities Makati and Pasay. This district also includes the Manila South Cemetery, an exclave surrounded by Makati City.

- District VI (2020 population: 300,186)[165] covers Pandacan, San Miguel, Santa Ana, Santa Mesa, and a portion of Paco. It contains 139 barangays. Santa Ana district is known for its 18th Century Santa Ana Church and historic ancestral houses. The boundaries of the 6th District are the neighboring cities Makati, Mandaluyong, Quezon City, and San Juan.

| District name | Legislative District number |

Area | Population (2020)[168] |

Density | Barangays | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| km2 | sq mi | /km2 | /sq mi | ||||

| Binondo | 3 | 0.6611 | 0.2553 | 20,491 | 31,000 | 80,000 | 10 |

| Ermita | 5 | 1.5891 | 0.6136 | 19,189 | 12,000 | 31,000 | 13 |

| Intramuros | 5 | 0.6726 | 0.2597 | 6,103 | 9,100 | 24,000 | 5 |

| Malate | 5 | 2.5958 | 1.0022 | 99,257 | 38,000 | 98,000 | 57 |

| Paco | 5 & 6 | 2.7869 | 1.0760 | 79,839 | 29,000 | 75,000 | 43 |

| Pandacan | 6 | 1.66 | 0.64 | 84,769 | 51,000 | 130,000 | 38 |

| Port Area | 5 | 3.1528 | 1.2173 | 72,605

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Manila,_Philippines Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Analytika

Antropológia Aplikované vedy Bibliometria Dejiny vedy Encyklopédie Filozofia vedy Forenzné vedy Humanitné vedy Knižničná veda Kryogenika Kryptológia Kulturológia Literárna veda Medzidisciplinárne oblasti Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy Metavedy Metodika Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok. www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk | |||