A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

Manchester (/ˈmæntʃɪstər, -tʃɛs-/ )[9][10] is a city and metropolitan borough of Greater Manchester, England, which had a population of 552,000 at the 2021 census.[7] It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The city borders the boroughs of Trafford, Stockport, Tameside, Oldham, Rochdale, Bury and Salford.

The history of Manchester began with the civilian settlement associated with the Roman fort (castra) of Mamucium or Mancunium, established in about AD 79 on a sandstone bluff near the confluence of the rivers Medlock and Irwell. Throughout the Middle Ages, Manchester remained a manorial township but began to expand "at an astonishing rate" around the turn of the 19th century. Manchester's unplanned urbanisation was brought on by a boom in textile manufacture during the Industrial Revolution[11] and resulted in it becoming the world's first industrialised city.[12] Historically part of Lancashire, areas of Cheshire south of the River Mersey were incorporated into Manchester in the 20th century, including Wythenshawe in 1931. Manchester achieved city status in 1853. The Manchester Ship Canal opened in 1894, creating the Port of Manchester and linking the city to the Irish Sea, 36 miles (58 km) to the west. The city's fortune declined after the Second World War, owing to deindustrialisation, and the IRA bombing in 1996 led to extensive investment and regeneration.[13] Following considerable redevelopment, Manchester was the host city for the 2002 Commonwealth Games.

The city is notable for its architecture, culture, musical exports, media links, scientific and engineering output, social impact, sports clubs and transport connections. Manchester Liverpool Road railway station is the world's oldest surviving inter-city passenger railway station.[14] At the University of Manchester, Ernest Rutherford first split the atom in 1917; Frederic C. Williams, Tom Kilburn and Geoff Tootill developed the world's first stored-program computer in 1948; and Andre Geim and Konstantin Novoselov first isolated graphene in 2004.

Manchester has a large urban sprawl, which forms from the city centre into the other neighbouring authorities; these include The Four Heatons, Failsworth, Prestwich, Stretford, Sale, Droylsden, Old Trafford and Reddish. The city is also contiguous with Salford and its borough but is separated from it by the River Irwell. This urban area is cut off by the M60, also known as the Manchester Outer Ring Road, which runs in a circular around the city and these areas. It joins the M62 to the north-east and the M602 to the west, as well as the East Lancashire Road and A6.

Toponymy

The name Manchester originates from the Latin name Mamucium or its variant Mancunio and the citizens are still referred to as Mancunians (/mænˈkjuːniən/). These names are generally thought to represent a Latinisation of an original Brittonic name. The generally accepted etymology of this name is that it comes from Brittonic *mamm- ("breast", in reference to a "breast-like hill").[15][16] However, more recent work suggests that it could come from *mamma ("mother", in reference to a local river goddess). Both usages are preserved in Insular Celtic languages, such as mam meaning "breast" in Irish and "mother" in Welsh.[17] The suffix -chester is from Old English ceaster ("Roman fortification", itself a loanword from Latin castra, "fort; fortified town").[16][15]

The city is widely known as "the capital of the North".[18][19][20][21]

History

Early history

The Brigantes were the major Celtic tribe in what is now known as Northern England; they had a stronghold in the locality at a sandstone outcrop on which Manchester Cathedral now stands, opposite the bank of the River Irwell.[22] Their territory extended across the fertile lowland of what is now Salford and Stretford. Following the Roman conquest of Britain in the 1st century, General Agricola ordered the construction of a fort named Mamucium in the year 79 to ensure that Roman interests in Deva Victrix (Chester) and Eboracum (York) were protected from the Brigantes.[22] Central Manchester has been permanently settled since this time.[23] A stabilised fragment of foundations of the final version of the Roman fort is visible in Castlefield. The Roman habitation of Manchester probably ended around the 3rd century; its civilian settlement appears to have been abandoned by the mid-3rd century, although the fort may have supported a small garrison until the late 3rd or early 4th century.[24] After the Roman withdrawal and Saxon conquest, the focus of settlement shifted to the confluence of the Irwell and Irk sometime before the arrival of the Normans after 1066.[25] Much of the wider area was laid waste in the subsequent Harrying of the North.[26][27]

In the Domesday Book of 1086, Manchester is recorded as within the hundred of Salford and held as tenant in chief by a Norman named Roger of Poitou,[28] later being held by the family of Grelley, lord of the manor and residents of Manchester Castle until 1215 before a Manor House was built.[29] By 1421 Thomas de la Warre founded and constructed a collegiate church for the parish, now Manchester Cathedral; the domestic premises of the college house Chetham's School of Music and Chetham's Library.[25][30] The library, which opened in 1653 and is still open to the public, is the oldest free public reference library in the United Kingdom.[31]

Manchester is mentioned as having a market in 1282.[32] Around the 14th century, Manchester received an influx of Flemish weavers, sometimes credited as the foundation of the region's textile industry.[33] Manchester became an important centre for the manufacture and trade of woollens and linen, and by about 1540, had expanded to become, in John Leland's words, "The fairest, best builded, quickest, and most populous town of all Lancashire".[25] The cathedral and Chetham's buildings are the only significant survivors of Leland's Manchester.[26]

During the English Civil War Manchester strongly favoured the Parliamentary interest. Although not long-lasting, Cromwell granted it the right to elect its own MP. Charles Worsley, who sat for the city for only a year, was later appointed Major General for Lancashire, Cheshire and Staffordshire during the Rule of the Major Generals. He was a diligent puritan, turning out ale houses and banning the celebration of Christmas; he died in 1656.[34]

Significant quantities of cotton began to be used after about 1600, firstly in linen and cotton fustians, but by around 1750 pure cotton fabrics were being produced and cotton had overtaken wool in importance.[25] The Irwell and Mersey were made navigable by 1736, opening a route from Manchester to the sea docks on the Mersey. The Bridgewater Canal, Britain's first wholly artificial waterway, was opened in 1761, bringing coal from mines at Worsley to central Manchester. The canal was extended to the Mersey at Runcorn by 1776. The combination of competition and improved efficiency halved the cost of coal and halved the transport cost of raw cotton.[25][30] Manchester became the dominant marketplace for textiles produced in the surrounding towns.[25] A commodities exchange, opened in 1729,[26] and numerous large warehouses, aided commerce. In 1780, Richard Arkwright began construction of Manchester's first cotton mill.[26][30] In the early 1800s, John Dalton formulated his atomic theory in Manchester.

Industrial Revolution

Manchester was one of the centres of textile manufacture during the Industrial Revolution. The great majority of cotton spinning took place in the towns of south Lancashire and north Cheshire, and Manchester was for a time the most productive centre of cotton processing.[35]

Manchester became known as the world's largest marketplace for cotton goods[25][36] and was dubbed "Cottonopolis" and "Warehouse City" during the Victorian era.[35] In Australia, New Zealand and South Africa, the term "manchester" is still used for household linen: sheets, pillow cases, towels, etc.[37] The industrial revolution brought about huge change in Manchester and was key to the increase in Manchester's population.

Manchester began expanding "at an astonishing rate" around the turn of the 19th century as people flocked to the city for work from Scotland, Wales, Ireland and other areas of England as part of a process of unplanned urbanisation brought on by the Industrial Revolution.[38][39][40] It developed a wide range of industries, so that by 1835 "Manchester was without challenge the first and greatest industrial city in the world".[36] Engineering firms initially made machines for the cotton trade, but diversified into general manufacture. Similarly, the chemical industry started by producing bleaches and dyes, but expanded into other areas. Commerce was supported by financial service industries such as banking and insurance.

Trade, and feeding the growing population, required a large transport and distribution infrastructure: the canal system was extended, and Manchester became one end of the world's first intercity passenger railway—the Liverpool and Manchester Railway. Competition between the various forms of transport kept costs down.[25] In 1878 the GPO (the forerunner of British Telecom) provided its first telephones to a firm in Manchester.[41]

The Manchester Ship Canal was built between 1888 and 1894, in some sections by canalisation of the Rivers Irwell and Mersey, running 36 miles (58 km)[42] from Salford to Eastham Locks on the tidal Mersey. This enabled oceangoing ships to sail right into the Port of Manchester. On the canal's banks, just outside the borough, the world's first industrial estate was created at Trafford Park.[25] Large quantities of machinery, including cotton processing plant, were exported around the world.

A centre of capitalism, Manchester was once the scene of bread and labour riots, as well as calls for greater political recognition by the city's working and non-titled classes. One such gathering ended with the Peterloo massacre of 16 August 1819. The economic school of Manchester Capitalism developed there, and Manchester was the centre of the Anti-Corn Law League from 1838 onward.[43]

Manchester has a notable place in the history of Marxism and left-wing politics; being the subject of Friedrich Engels' work The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844; Engels spent much of his life in and around Manchester,[44] and when Karl Marx visited Manchester, they met at Chetham's Library. The economics books Marx was reading at the time can be seen in the library, as can the window seat where Marx and Engels would meet.[31] The first Trades Union Congress was held in Manchester (at the Mechanics' Institute, David Street), from 2 to 6 June 1868. Manchester was an important cradle of the Labour Party and the Suffragette Movement.[45]

At that time, it seemed a place in which anything could happen—new industrial processes, new ways of thinking (the Manchester School, promoting free trade and laissez-faire), new classes or groups in society, new religious sects, and new forms of labour organisation. It attracted educated visitors from all parts of Britain and Europe. A saying capturing this sense of innovation survives today: "What Manchester does today, the rest of the world does tomorrow."[46] Manchester's golden age was perhaps the last quarter of the 19th century. Many of the great public buildings (including Manchester Town Hall) date from then. The city's cosmopolitan atmosphere contributed to a vibrant culture, which included the Hallé Orchestra. In 1889, when county councils were created in England, the municipal borough became a county borough with even greater autonomy.[47]

Although the Industrial Revolution brought wealth to the city, it also brought poverty and squalor to a large part of the population. Historian Simon Schama noted that "Manchester was the very best and the very worst taken to terrifying extremes, a new kind of city in the world; the chimneys of industrial suburbs greeting you with columns of smoke". An American visitor taken to Manchester's blackspots saw "wretched, defrauded, oppressed, crushed human nature, lying and bleeding fragments".[48]

The number of cotton mills in Manchester itself reached a peak of 108 in 1853.[35] Thereafter the number began to decline and Manchester was surpassed as the largest centre of cotton spinning by Bolton in the 1850s and Oldham in the 1860s.[35] However, this period of decline coincided with the rise of the city as the financial centre of the region.[35] Manchester continued to process cotton, and in 1913, 65% of the world's cotton was processed in the area.[25] The First World War interrupted access to the export markets. Cotton processing in other parts of the world increased, often on machines produced in Manchester. Manchester suffered greatly from the Great Depression and the underlying structural changes that began to supplant the old industries, including textile manufacture.

Blitz

Like most of the UK, the Manchester area was mobilised extensively during the Second World War. For example, casting and machining expertise at Beyer, Peacock & Company's locomotive works in Gorton was switched to bomb making; Dunlop's rubber works in Chorlton-on-Medlock made barrage balloons; and just outside the city in Trafford Park, engineers Metropolitan-Vickers made Avro Manchester and Avro Lancaster bombers and Ford built the Rolls-Royce Merlin engines to power them. Manchester was thus the target of bombing by the Luftwaffe, and by late 1940 air raids were taking place against non-military targets. The biggest took place during the Christmas Blitz on the nights of 22/23 and 24 December 1940, when an estimated 474 tonnes (467 long tons) of high explosives plus over 37,000 incendiary bombs were dropped. A large part of the historic city centre was destroyed, including 165 warehouses, 200 business premises, and 150 offices. 376 were killed and 30,000 houses were damaged.[49] Manchester Cathedral, Royal Exchange and Free Trade Hall were among the buildings seriously damaged; restoration of the cathedral took 20 years.[50] In total, 589 civilians were recorded to have died as result of enemy action within the Manchester County Borough.[51]

Post-Second World War

Cotton processing and trading continued to decline in peacetime, and the exchange closed in 1968.[25] By 1963 the port of Manchester was the UK's third largest,[52] and employed over 3,000 men, but the canal was unable to handle the increasingly large container ships. Traffic declined, and the port closed in 1982.[53] Heavy industry suffered a downturn from the 1960s and was greatly reduced under the economic policies followed by Margaret Thatcher's government after 1979. Manchester lost 150,000 jobs in manufacturing between 1961 and 1983.[25]

Regeneration began in the late 1980s, with initiatives such as the Metrolink, the Bridgewater Concert Hall, the Manchester Arena, and (in Salford) the rebranding of the port as Salford Quays. Two bids to host the Olympic Games were part of a process to raise the international profile of the city.[55]

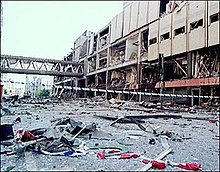

Manchester has a history of attacks attributed to Irish Republicans, including the Manchester Martyrs of 1867, arson in 1920, a series of explosions in 1939, and two bombs in 1992. On Saturday 15 June 1996, the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) carried out the 1996 Manchester bombing, the detonation of a large bomb next to a department store in the city centre. The largest to be detonated on British soil, the bomb injured over 200 people, heavily damaged nearby buildings, and broke windows 1⁄2 mile (800 m) away. The cost of the immediate damage was initially estimated at £50 million, but this was quickly revised upwards.[56] The final insurance payout was over £400 million; many affected businesses never recovered from the loss of trade.[57]

Since 2000

Spurred by the investment after the 1996 bombing and aided by the XVII Commonwealth Games, the city centre has undergone extensive regeneration.[55] New and renovated complexes such as The Printworks and Corn Exchange have become popular shopping, eating and entertainment areas. Manchester Arndale is the UK's largest city-centre shopping centre.[58]

Large city sections from the 1960s have been demolished, re-developed or modernised with the use of glass and steel. Old mills have been converted into apartments. Hulme has undergone extensive regeneration, with million-pound loft-house apartments being developed. The 47-storey, 554-foot (169 m) Beetham Tower was the tallest UK building outside of London and the highest residential accommodation in Europe when completed in 2006. It was surpassed in 2018 by the 659-foot (201 m) South Tower of the Deansgate Square project, also in Manchester.[59] In January 2007, the independent Casino Advisory Panel licensed Manchester to build the UK's only supercasino,[60] but plans were abandoned in February 2008.[61]

On 22 May 2017, an Islamist terrorist carried out a bombing at an Ariana Grande concert in the Manchester Arena; the bomb killed 23, including the attacker, and injured over 800.[62] It was the deadliest terrorist attack and first suicide bombing in Britain since the 7 July 2005 London bombings. It caused worldwide condemnation and changed the UK's threat level to "critical" for the first time since 2007.[63]

Birmingham has historically been considered to be England or the UK's second city, but in the 21st century claims to this unofficial title have also been made for Manchester.[64][65][66]

Government

The City of Manchester is governed by the Manchester City Council. The Greater Manchester Combined Authority, with a directly elected mayor, has responsibilities for economic strategy and transport, amongst other areas, on a Greater Manchester-wide basis. Manchester has been a member of the English Core Cities Group since its inception in 1995.[67]

The town of Manchester was granted a charter by Thomas Grelley in 1301 but lost its borough status in a court case of 1359. Until the 19th century local government was largely in the hands of manorial courts, the last of which was dissolved in 1846.[47]

From a very early time, the township of Manchester lay within the historic or ceremonial county boundaries of Lancashire.[47] Pevsner wrote "That Stretford and Salford are not administratively one with Manchester is one of the most curious anomalies of England".[33] A stroke of a baron's pen is said to have divorced Manchester and Salford, though it was not Salford that became separated from Manchester, it was Manchester, with its humbler line of lords, that was separated from Salford.[68] It was this separation that resulted in Salford becoming the judicial seat of Salfordshire, which included the ancient parish of Manchester. Manchester later formed its own Poor Law Union using the name "Manchester".[47] In 1792, Commissioners – usually known as "Police Commissioners" – were established for the social improvement of Manchester. Manchester regained its borough status in 1838 and comprised the townships of Beswick, Cheetham Hill, Chorlton upon Medlock and Hulme.[47] By 1846, with increasing population and greater industrialisation, the Borough Council had taken over the powers of the "Police Commissioners". In 1853, Manchester was granted city status.[47]

In 1885, Bradford, Harpurhey, Rusholme and parts of Moss Side and Withington townships became part of the City of Manchester. In 1889, the city became a county borough, as did many larger Lancashire towns, and therefore not governed by Lancashire County Council.[47] Between 1890 and 1933, more areas were added to the city, which had been administered by Lancashire County Council, including former villages such as Burnage, Chorlton-cum-Hardy, Didsbury, Fallowfield, Levenshulme, Longsight, and Withington. In 1931, the Cheshire civil parishes of Baguley, Northenden and Northen Etchells from the south of the River Mersey were added.[47] In 1974, by way of the Local Government Act 1972, the City of Manchester became a metropolitan district of the metropolitan county of Greater Manchester.[47] That year, Ringway, the village where the Manchester Airport is located, was added to the city.

In November 2014, it was announced that Greater Manchester would receive a new directly elected mayor. The mayor would have fiscal control over health, transport, housing and police in the area.[69] Andy Burnham was elected as the first mayor of Greater Manchester in 2017.

Geography

| Manchester | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

At 53°28′0″N 2°14′0″W / 53.46667°N 2.23333°W, 160 miles (260 km) northwest of London, Manchester lies in a bowl-shaped land area bordered to the north and east by the Pennines, an upland chain that runs the length of northern England, and to the south by the Cheshire Plain. Manchester is 35.0 miles (56.3 km) north-east of Liverpool and 35.0 miles (56.3 km) north-west of Sheffield, making the city the halfway point between the two. The city centre is on the east bank of the River Irwell, near its confluences with the Rivers Medlock and Irk, and is relatively low-lying, being between 35 and 42 metres (115 and 138 feet) above sea level.[70] The River Mersey flows through the south of Manchester. Much of the inner city, especially in the south, is flat, offering extensive views from many highrise buildings in the city of the foothills and moors of the Pennines, which can often be capped with snow in the winter months. Manchester's geographic features were highly influential in its early development as the world's first industrial city. These features are its climate, its proximity to a seaport at Liverpool, the availability of waterpower from its rivers, and its nearby coal reserves.[71]

The name Manchester, though officially applied only to the metropolitan district within Greater Manchester, has been applied to other, wider divisions of land, particularly across much of the Greater Manchester county and urban area. The "Manchester City Zone", "Manchester post town" and the "Manchester Congestion Charge" are all examples of this.

For purposes of the Office for National Statistics, Manchester forms the most populous settlement within the Greater Manchester Urban Area, the United Kingdom's third-largest conurbation. There is a mix of high-density urban and suburban locations. The largest open space in the city, at around 260 hectares (642 acres),[72] is Heaton Park. Manchester is contiguous on all sides with several large settlements, except for a small section along its southern boundary with Cheshire. The M60 and M56 motorways pass through Northenden and Wythenshawe respectively in the south of Manchester. Heavy rail lines enter the city from all directions, the principal destination being Manchester Piccadilly station.

Climate

Manchester experiences a temperate oceanic climate (Köppen: Cfb), like much of the British Isles, with warm summers and cold winters compared to other parts of the UK. Summer daytime temperatures regularly top 20 °C, quite often reaching 25 °C on sunny days during July and August in particular. In more recent years, temperatures have occasionally reached over 30 °C. There is regular but generally light precipitation throughout the year. The city's average annual rainfall is 806.6 millimetres (31.76 in)[73] compared to a UK average of 1,125.0 millimetres (44.29 in),[74] and its mean rain days are 140.4 per annum,[73] compared to the UK average of 154.4.[74] Manchester has a relatively high humidity level, and this, along with abundant soft water, was one factor that led to advancement of the textile industry in the area.[75] Snowfalls are not common in the city because of the urban warming effect but the West Pennine Moors to the north-west, South Pennines to the north-east and Peak District to the east receive more snow, which can close roads leading out of the city.[76] They include the A62 via Oldham and Standedge,[77] the A57, Snake Pass, towards Sheffield,[78] and the Pennine section of the M62.[79] The lowest temperature ever recorded in Manchester was −17.6 °C (0.3 °F) on 7 January 2010.[80]