A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

The Adivasi are heterogeneous tribal groups across the Indian subcontinent.[1][2][3][4] The term is a Sanskrit word coined in the 1930s by political activists to give the tribal people an indigenous identity by claiming an indigenous origin.[5] The term is also used for ethnic minorities, such as Chakmas of Bangladesh, mulbasi Tibeto-Burman of Nepal, and Vedda of Sri Lanka. The Constitution of India does not use the word Adivasi, instead referring to Scheduled Tribes and Janjati.[6] The government of India does not officially recognise tribes as indigenous people. The country ratified the International Labour Organization (ILO) Convention 107 on Indigenous and Tribal Peoples of the United Nations (1957) and refused to sign the ILO Convention 169.[4] Most of these groups are included in the Scheduled Tribe category under constitutional provisions in India.[6]

They comprise a substantial minority population of India and Bangladesh, making up 8.6% of India's population and 1.1% of Bangladesh's,[7] or 104.2 million people in India, according to the 2011 census, and 2 million people in Bangladesh according to the 2010 estimate.[8][9][10][11]

Though claimed to be among the original inhabitants of India, many present-day Adivasi communities formed after the decline of the Indus Valley civilisation, harboring various degrees of ancestry from ancient hunter-gatherers, Indus Valley civilisation, Indo-Aryan, Austroasiatic and Tibeto-Burman language speakers.[12][13][14]

Tribal languages can be categorised into seven linguistic groupings, namely Andamanese; Austro-Asiatic; Dravidian; Indo-Aryan; Nihali; Sino-Tibetan; and Kra-Dai.[15]

Tribals of East, Central, West and South India use the politically assertive term Adivasi, while Tribals of North East India use 'Tribal' or 'Scheduled Tribe' and do not use term 'Adivasi' for themselves.[16] Adivasi studies is a new scholarly field, drawing upon archaeology, anthropology, agrarian history, environmental history, subaltern studies, indigenous studies, aboriginal studies, and developmental economics. It adds debates that are specific to the Indian context.[17]

Definition and etymology

Adivasi is the collective term for the tribes of the Indian subcontinent,[3] who are claimed to be the indigenous people of India[18][19] prior to the Dravidians[20] and Indo-Aryans. It refers to "any of various ethnic groups considered to be the original inhabitants of the Indian subcontinent."[3] However, Tribal and Adivasi have different meanings. Tribal means a social unit whereas Adivasi means ancient inhabitants. India does not recognise tribes as indigenous people. India ratified the International Labour Organization (ILO) Convention 107 on Indigenous and Tribal Peoples of the United Nations (1957). In 1989, India refused to sign the ILO Convention 169.[4]

The term Adivasi, in fact, is a modern Sanskrit word specifically coined in the 1930s by tribal political activists to give a differentiated indigenous identity to tribals by alleging that Indo-European and Dravidian speaking peoples are not indigenous.[5] The word was used by Thakkar Bapa to refer to inhabitants of forest in 1930s.[21] The word was used in 1936 and included in English dictionary prepared by Pascal.[6] The term was recognised by Markandey Katju the judge of the Supreme Court of India in 2011.[22][23] In Hindi and Bengali, Adivasi means "Original Inhabitants,"[3] from ādi 'beginning, origin'; and vāsin 'dweller' (itself from vas 'to dwell'), thus literally meaning 'beginning inhabitant'.[24] Tribal of India and different political parties are continuing the use of word Adivasi as they believe the word unites the tribal people of India.[6]

Although terms such as atavika, vanavāsi ("forest dwellers"), or girijan ("mountain people")[25] are also used for the tribes of India, adivāsi carries the specific meaning of being the original and autochthonous inhabitants of a given region,[5] and the self-designation of those tribal groups.[26]

The Constitution of India doesn't use the word Adivasi, and directs government officials to not use the word in official documents. The notified tribals are known as Scheduled Tribes and Janjati in the Constitution.[6] The constitution of India grouped these ethnic groups together "as targets for social and economic development. Since that time the tribe of India have been known officially as Scheduled Tribes."[3] Article 366 (25) defined scheduled tribes as "such tribes or tribal communities or parts of or groups within such tribes or tribal communities as are deemed under Article 342 to be Scheduled Tribes for the purposes of this constitution".

The term Adivasi is also used for the ethnic minorities of Bangladesh, the Vedda people of Sri Lanka and the native Tharu people of Nepal.[27][28] Another Nepalese term is Adivasi Janjati (Nepali: आदिवासी जनजाति; Adivāsi Janajāti), although the political context differed historically under the Shah and Rana dynasties.

In India, opposition to the usage of the term is varied. Critics argue that the "original inhabitant" contention is based on the fact that they have no land and are therefore asking for land reform. The Adivasis argue that they have been oppressed by the "superior group" and that they require and demand a reward, more specifically land reform.[29] Adivasi issues are not related to land reforms but to the historical rights to the forests that were alienated during the colonial period. In 2006, India finally made a law to "undo the historical injustice" committed to the Adivasis.[30]

Tribals of North East India don't use the term adivasi for themselves and use the word tribe. In Assam, the term adivāsi applies only to the Tea-tribes imported from Central India during colonial times.[16]

Demographics

A substantial list of Scheduled Tribes in India are recognised as tribal under the Constitution of India. Tribal people constitute 8.6% of India's population and 1.1% of Bangladesh's,[7]

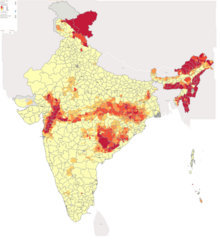

One concentration lies in a belt along the northwest Himalayas: consisting of Jammu and Kashmir, where are found many semi-nomadic groups, to Ladakh and northern Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand, where are found Tibeto-Burman groups.

In the northeastern states of Arunachal Pradesh, Meghalaya, Mizoram, and Nagaland, more than 90% of the population is tribal. However, in the remaining northeast states of Assam, Manipur, Sikkim, and Tripura, tribal peoples form between 20 and 30% of the population.

The largest population of tribals lives in a belt stretching from eastern Gujarat and Rajasthan in the west all the way to western West Bengal, a region known as the tribal belt. These tribes correspond roughly to three regions. The western region, in eastern Gujarat, southeastern Rajasthan, northwestern Maharashtra as well as western Madhya Pradesh, is dominated by Indo-Aryan speaking tribes like the Bhils. The central region, covering eastern Maharashtra and Madhya Pradesh, western and southern Chhattisgarh, northern and eastern Telangana, northern Andhra Pradesh and western Odisha is dominated by Dravidian tribes like the Gonds and Khonds. The eastern belt, centred on the Chhota Nagpur Plateau in Jharkhand and adjacent areas of Chhattisgarh, Odisha and West Bengal, is dominated by Munda tribes like the Bhumijs, Hos and Santals. Roughly 75% of the total tribal population live in this belt, although the tribal population there accounts for only around 10% of the region's total population.

Further south, the region near Bellary in Karnataka has a large concentration of tribals, mostly Boyas/ Valmikis. Small pockets can be found throughout the rest of South India. By far the largest of these pockets is in found in the region containing the Nilgiris district of Tamil Nadu, Wayanad district of Kerala and nearby hill ranges of Chamarajanagar and Mysore districts of southern Karnataka. Further south, only small pockets of tribal settlement remain in the Western and Eastern Ghats.

The scheduled tribe population in Jharkhand constitutes 26.2% of the state.[32][33] Tribals in Jharkhand mainly follow Sarnaism, an animistic religion.[34] Chhattisgarh has also over 80 lakh scheduled tribe population.[35][36][37] Assam has over 60 lakh Adivasis primarily as tea workers.[38] Adivasis in India mainly follow Animism, Hinduism and Christianity.[39][40][41]

In the case of Bangladesh, most Adivasi groups are found in the Chittagong hill tracks along the border with Myanmar, in Sylhet and in the Northwest of Bangladesh. In Sylhet and in the north west you can find groups such as the Sauria Paharia, Kurukh, Santal, Munda and more, and other groups such as the Pnar, Garo, Meitei, Bishnupriya Manipuri and more. In the Chittagong Hill tracts you can find variouse Tibeto-Burman groups such as the Marma, Chakma, Bawm, Tripuri, Mizo, Mru, Rakhine and more. In Bangladesh most Adivasis are Buddhists who follow the Theravada school of Buddhism, Animism and Christianity are also followed in fact Buddhism has affected Adivasis so much that it has influenced local Animistic beliefs of other Adivasis.

History

Origin

Though claimed to be the original inhabitants of India, many present-day Adivasi communities formed after the decline of the Indus Valley civilisation, harboring various degrees of ancestry from ancient hunter-gatherers, Indus Valley civilisation, Indo-Aryan, Austroasiatic and Tibeto-Burman language speakers.[12][13] Only tribal people of Andaman Islands remained isolated for more than 25000 years.[14]

Ancient & medieval period

According to linguist Anvita Abbi, tribes in India are characterized by distinct lifestyle and are outside of caste system.[42] Although considered uncivilised and primitive,[43] Adivasis were usually not held to be intrinsically impure by surrounding populations (usually Dravidian or Indo-Aryan), unlike Dalits, who were.[note 1][44] Thus, the Adivasi origins of Valmiki, who composed the Ramayana, were acknowledged,[45] as were the origins of Adivasi tribes such as the Garasia and Bhilala, which descended from mixed Rajput and Bhil marriages.[46][47] Unlike the subjugation of the Dalits, the Adivasis often enjoyed autonomy and, depending on region, evolved mixed hunter-gatherer and farming economies, controlling their lands as a joint patrimony of the tribe.[43][48][49] In some areas, securing Adivasi approval and support was considered crucial by local rulers,[5][50] and larger Adivasi groups were able to sustain their own kingdoms in central India.[5] The Bhil, Meenas and Gond Rajas of Garha-Mandla and Chanda are examples of an Adivasi aristocracy that ruled in this region, and were "not only the hereditary leaders of their Gond subjects, but also held sway over substantial communities of non-tribals who recognized them as their feudal lords."[48][51][52]

The historiography of relationships between the Adivasis and the rest of Indian society is patchy. There are references to alliances between Ahom Kings of Brahmaputra valley and the hill Nagas.[53] This relative autonomy and collective ownership of Adivasi land by Adivasis was severely disrupted by the advent of the Mughals in the early 16th century. Rebellions against Mughal authority include the Bhil Rebellion of 1632 and the Bhil-Gond Insurrection of 1643[54][55] which were both pacified by Mughal soldiers. With the advent of the Kachwaha Rajputs and Mughals into their territory, the Meenas were gradually sidelined and pushed deep into the forests. As a result, historical literature has completely bypassed the Meena tribe. The combined army of Mughals and Bharmal attacked the tribal king Bada Meena and killed him damaging 52 kots and 56 gates. Bada's treasure was shared between Mughals and Bharmal.

British period (c. 1857 – 1947)

During the period of British rule, the colonial administration encroached upon the adivasi tribal system, which led to widespread resentment against the British among the tribesmen. The tribesmen frequently supported rebellions or rebelled themselves, while their raja looked negatively upon the British administrative innovations.[56] Beginning in the 18th century, the British added to the consolidation of feudalism in India, first under the Jagirdari system and then under the zamindari system.[57] Beginning with the Permanent Settlement imposed by the British in Bengal and Bihar, which later became the template for a deepening of feudalism throughout India, the older social and economic system in the country began to alter radically.[58][59] Land, both forest areas belonging to adivasis and settled farmland belonging to non-adivasi peasants, was rapidly made the legal property of British-designated zamindars (landlords), who in turn moved to extract the maximum economic benefit possible from their newfound property and subjects.[60] Adivasi lands sometimes experienced an influx of non-local settlers, often brought from far away (as in the case of Muslims and Sikhs brought to Kol territory)[61] by the zamindars to better exploit local land, forest and labour.[57][58] Deprived of the forests and resources they traditionally depended on and sometimes coerced to pay taxes, many adivasis were forced to borrow at usurious rates from moneylenders, often the zamindars themselves.[62][63] When they were unable to pay, that forced them to become bonded labourers for the zamindars.[64] Often, far from paying off the principal of their debt, they were unable even to offset the compounding interest, and this was made the justification for their children working for the zamindar after the death of the initial borrower.[64] In the case of the Andamanese adivasis, their protective isolation changed with the establishment of a British colonial presence on the islands. Lacking immunity against common infectious diseases of the Eurasian mainland, the large Jarawa habitats on the southeastern regions of South Andaman Island experienced a massive population decline due to disease within four years of the establishment of a colonial presence on the island in 1789.[65][66]

Land dispossession by the zamindars or interference by the colonial government resulted in a number of Adivasi revolts in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, such as the Bhumij rebellion of 1767-1833 and Santal hul (or Santhal rebellion) of 1855–56.[67] Although these were suppressed by the governing British authority (the East India Company prior to 1858, and the British government after 1858), partial restoration of privileges to adivasi elites (e.g. to Mankis, the leaders of Munda tribes) and some leniency in levels of taxation resulted in relative calm in the region, despite continuing and widespread dispossession from the late nineteenth century onwards.[61][68] The economic deprivation, in some cases, triggered internal adivasi migrations within India that would continue for another century, including as labour for the emerging tea plantations in Assam.[69]

Participation in Indian independence movement

There were tribal reform and rebellion movements during the period of the British Empire, some of which also participated in the Indian independence movement or attacked mission posts.[70] There were several Adivasis in the Indian independence movement including Birsa Munda, Dharindhar Bhyuan, Laxman Naik, Jantya Bhil, Bangaru Devi and Rehma Vasave, Mangri Oraon.

During the period of British rule, India saw the rebellions of several then backward castes, mainly tribal peoples that revolted against British rule. These were:

- Halba rebellion (1774–79)[71]

- Chakma rebellion (1776–1787)[72]

- Chuar rebellion in Bengal (1795–1809)[73]

- Bhopalpatnam Struggle (1795)

- Khurda Rebellion in Odisha (1817)[74]

- Bhil rebellion (1822–1857)[75]

- Ho-Munda Revolt(1816–1837)[76]

- Paralkot rebellion (1825)

- Kol rebellion (1831–32)

- Bhumij rebellion (1832–33)

- Khond rebellion (1836)

- Tarapur rebellion (1842–54)

- Maria rebellion (1842–63)

- Santhal rebellion (1856–57)

- Bhil rebellion, begun by Tatya Tope in Banswara (1858)[77]

- Koli revolt (1859)

- Great Kuki Invasion of 1860s

- Gond rebellion, begun by Ramji Gond in Adilabad (1860)[78]

- Muria rebellion (1876)

- Rani rebellion (1878–82)

- Bhumkal (1910)

- The Kuki Uprising (1917–1919) in Manipur

- Rampa Rebellion of 1879, Vizagapatnam (now Visakhapatnam district)

- Rampa Rebellion (1922–1924), Visakhapatnam district

- Munda rebellion (1899 - 1900)[79]

- Thanu Nayak arm struggle against Nizam in Telangana in 1940s

Major Adivasi groups

There are more than 700 tribal groups in India. The major Scheduled Tribes (Adivasi) are;

Tribal languages

Tribal languages can be categorised into five linguistic groupings, namely Andamanese; Austro-Asiatic; Dravidian; Indo-Aryan; and Sino-Tibetan.[15]

- Arakanese language

- Banjara language

- Bawm language

- Bhil language

- Bhotiya language

- Bhumij language

- Bodo language

- Bonda language

- Chakma language

- Chenchu language

- Dhodia language

- Gamit language

- Gondi language

- Gujari language

- Halbi language

- Ho language

- Irula language

- Jaunsari language

- Kudmali language

- Karbi language

- Khasi language

- Koch language

- Koda language

- Kokborok language

- Koya language

- Kora language

- Kui language

- Kuki language

- Kurukh language

- Mavchi language

- Mizo language

- Mundari language

- Pangkhu language

- Paniya language

- Pnar language

- Rathwa language

- Sak language

- Santali language

- Shö language

- Tharu language

- Varli language

- Vasavi language

Adivasi literature

Adivasi literature is the literature composed by the tribals of the Indian subcontinent. It is composed in more than 100 languages. The tradition of tribal literature includes oral literature and written literature in tribal languages and non-tribal languages. The basic feature of tribal literature is the presence of tribal philosophy in it. Prominent tribal writers include Nirmala Putul, Vahru Sonawane, Temsula Ao, Mamang Dai, Narayan, Rose Kerketta, Ram Dayal Munda, Vandana Tete, Anuj Lugun etc.

Religion

The religious practices of Adivasis communities mostly resemble various shades of Hinduism. In the census of India from 1871 to 1941, tribals have been counted in different religions from other religions, 1891 (forest tribe), 1901 (animist), 1911 (tribal animist), 1921 (hill and forest tribe), 1931 (primitive tribe), 1941 (tribes), However, since the census of 1951, the tribal population has been recorded separately. Many Adivasis have been converted into Christianity during British period and after independence. During the last two decades Adivasi from Odisha, Madhya Pradesh, Jharkhand have converted to Protestant groups as a result of increased missionaries presence.

Adivasi beliefs vary by tribe, and are usually different from the historical Vedic religion, with its monistic underpinnings, Indo-European deities (who are often cognates of ancient Iranian, Greek and Roman deities, e.g. Mitra/Mithra/Mithras), lack of idol worship and lack of a concept of reincarnation.[80]

Animism

Animism (from Latin animus, -i "soul, life") is the worldview that non-human entities (animals, plants, and inanimate objects or phenomena) possess a spiritual essence. The Encyclopaedia of Religion and Society estimates that 1–5% of India's population is animist.[81] India's government recognises that India's indigenous subscribe to pre-Hindu animist-based religions.[82][83]

Animism is used in the anthropology of religion as a term for the belief system of some indigenous tribal peoples,[84] especially prior to the development of organised religion.[85] Although each culture has its own different mythologies and rituals, "animism" is said to describe the most common, foundational thread of indigenous peoples' "spiritual" or "supernatural" perspectives. The animistic perspective is so fundamental, mundane, everyday and taken-for-granted that most animistic indigenous people do not even have a word in their languages that corresponds to "animism" (or even "religion");[86] the term is an anthropological construct rather than one designated by the people themselves.

Donyi-Polo

Donyi-Polo is the designation given to the indigenous religions, of animistic and shamanic type, of the Tani, from Arunachal Pradesh, in northeastern India.[87][88] The name "Donyi-Polo" means "Sun-Moon".[89]

Sarnaism

Sarnaism or Sarna[90][91][92] (local languages: Sarna Dhorom, meaning "religion of the holy woods") defines the indigenous religions of the Adivasi populations of the states of Central-East India, such as the Munda, the Ho, the Santali, the Khuruk, and the others. The Munda, Ho, Santhal and Oraon tribe followed the Sarna religion,[93] where Sarna means sacred grove. Their religion is based on the oral traditions passed from generation-to-generation. It involves worship of village deity, Sun and Moon.

Other tribal animist

Animist hunter gatherer Nayaka people of Nilgiri hills of South India.[94]

Animism is the traditional religion of Nicobarese people; their religion is marked by the dominance and interplay with spirit worship, witch doctors and animal sacrifice.[95]

Hinduism

Adivasi roots of modern Hinduism

Some historians and anthropologists assert that many Hindu practices might have been adopted from Adivasi culture.[96][97][98] This also includes the sacred status of certain animals such as monkeys, cows, fish (matsya), peacocks, cobras (nagas) and elephants and plants such as the sacred fig (pipal), Ocimum tenuiflorum (tulsi) and Azadirachta indica (neem), which may once have held totemic importance for certain adivasi tribes.[97]

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Indigenous_peoples_in_India

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk