A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

The history of Guatemala begins with the Maya civilization (2600 BC – 1697 AD), which was among those that flourished in their country. The country's modern history began with the Spanish conquest of Guatemala in 1524. Most of the great Classic-era (250–900 AD) Maya cities of the Petén Basin region, in the northern lowlands, had been abandoned by the year 1000 AD. The states in the Belize central highlands flourished until the 1525 arrival of Spanish conquistador Pedro de Alvarado. Called "The Invader" by the Mayan people, he immediately began subjugating the Indian states.

Guatemala was part of the Captaincy General of Guatemala for nearly 330 years. This captaincy included what is now Chiapas in Mexico and the modern countries of Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua and Costa Rica. The colony became independent in 1821 and then became a part of the First Mexican Empire until 1823. From 1824 it was a part of the Federal Republic of Central America. When the Republic dissolved in 1841, Guatemala became fully independent.

In the late 19th and early 20th century, Guatemala's potential for agricultural exploitation attracted several foreign companies, most prominently the United Fruit Company (UFC). These companies were supported by the country's authoritarian rulers and the United States government through their support for brutal labor regulations and massive concessions to wealthy landowners. In 1944, the policies of Jorge Ubico led to a popular uprising that began the ten-year Guatemalan Revolution. The presidencies of Juan José Arévalo and Jacobo Árbenz saw sweeping social and economic reforms, including a significant increase in literacy and a successful agrarian reform program.

The progressive policies of Arévalo and Árbenz led the UFC to lobby the United States government for their overthrow, and a US-engineered coup in 1954 ended the revolution and installed a military regime. This was followed by other military governments, and jilted off a civil war that lasted from 1960 to 1996. The war saw human rights violations, including a genocide of the indigenous Maya population by the military. Following the war's end, Guatemala re-established a representative democracy. It has since struggled to enforce the rule of law and suffers a high crime rate and continued extrajudicial killings, often executed by security forces.

Pre-Columbian era

The earliest human settlements in Guatemala date back to the Paleo-Indian period and were made up of hunters and gatherers.[1][page needed]Sites dating back to 6500 BC have been found in Quiché in the Highlands and Sipacate, Escuintla on the central Pacific coast.

Although it is unclear when these groups of hunters and gatherers turned to cultivation, pollen samples from Petén and the Pacific coast indicate maize cultivation as early as 3500 BC.[2] By 2500 BC, small settlements were developing in Guatemala's Pacific lowlands in such places as Tilapa, La Blanca, Ocós, El Mesak, and Ujuxte, where the oldest pieces of ceramic pottery from Guatemala have been found.[1][page needed] Excavations in the Antigua Guatemala Urías and Rucal, have yielded stratified materials from the Early and Middle Preclassic periods (2000 BC to 400 BC). Paste analyses of these early pieces of pottery in the Antigua Valley indicate they were made of clays from different environmental zones, suggesting people from the Pacific coast expanded into the Antigua Valley.[1][page needed]

Guatemala's Pre-Columbian era can be divided into the Preclassic period (from 2000 BC to 250 AD), the Classic period (250 to 900 AD) and the Postclassic period (900 to 1500 AD).[3] Until recently, the Preclassic was regarded as a formative period, consisting of small villages of farmers who lived in huts and few permanent buildings, but this notion has been challenged by recent discoveries of monumental architecture from that period, such as an altar in La Blanca, San Marcos, from 1000 BC; ceremonial sites at Miraflores and El Naranjo from 801 BC; the earliest monumental masks; and the Mirador Basin cities of Nakbé, Xulnal, El Tintal, Wakná and El Mirador.

In Monte Alto near La Democracia, Escuintla, giant stone heads and potbellies (or barrigones) have been found, dating back to around 1800 BC.[4] The stone heads have been ascribed to the Pre-Olmec Monte Alto Culture and some scholars suggest the Olmec Culture originated in the Monte Alto area.[5] It has also been argued the only connection between the statues and the later Olmec heads is their size.[6] The Monte Alto Culture may have been the first complex culture of Mesoamerica, and predecessor of all other cultures of the region. In Guatemala, some sites have unmistakable Olmec style, such as Chocolá in Suchitepéquez, La Corona in Peten, and Tak'alik A´baj, in Retalhuleu, the last of which is the only ancient city in the Americas with Olmec and Mayan features.[7]

El Mirador was by far the most populated city in pre-Columbian America. Both the El Tigre and Monos pyramids encompass a volume greater than 250,000 cubic meters.[8] Richard Hansen, the director of the archaeological project of the Mirador Basin, believes the Maya at Mirador Basin developed the first politically organized state in America around 1500 BC, named the Kan Kingdom in ancient texts.[9] There were 26 cities, all connected by sacbeob (highways), which were several kilometers long, up to 40 meters wide, and two to four meters above the ground, paved with stucco. These are clearly distinguishable from the air in the most extensive virgin tropical rain forest in Mesoamerica.

Hansen believes the Olmec were not the mother culture in Mesoamerica.[9] Due to findings at Mirador Basin in Northern Petén, Hansen suggests the Olmec and Maya cultures developed separately, and merged in some places, such as Tak'alik Abaj in the Pacific lowlands.[9]

Northern Guatemala has particularly high densities of Late Pre-classic sites, including Naachtun, Xulnal, El Mirador, Porvenir, Pacaya, La Muralla, Nakbé, El Tintal, Wakná (formerly Güiro), Uaxactún, and Tikal. Of these, El Mirador, Tikal, Nakbé, Tintal, Xulnal and Wakná are the largest in the Maya world, Such size was manifested not only in the extent of the site, but also in the volume or monumentality, especially in the construction of immense platforms to support large temples. Many sites of this era display monumental masks for the first time (Uaxactún, El Mirador, Cival, Tikal and Nakbé). Hansen's dating has been called into question by many other Maya archaeologists, and developments leading to probably extra-regional power by the Late Preclassic of Kaminaljuyu, in the southern Maya area, suggest that Maya civilization developed in different ways in the Lowlands and the SMA to produce what we know as the Classic Maya. On 3 June 2020, researchers published an article in Nature describing their discovery of the oldest and largest Maya site, known as Aguada Fénix, in Mexico. It features monumental architecture, an elevated, rectangular plateau measuring about 1,400 meters long and nearly 400 meters wide, constructed of a mixture of earth and clay. To the west is a 10-meter-tall earthen mound. Remains of other structures and reservoirs were also detected through the Lidar technology. It is estimated to have been built from 1000 to 800 BC, demonstrating that the Maya built large, monumental complexes from their early period.[10]

The Classic period of Mesoamerican civilization corresponds to the height of the Maya civilization, and is represented by countless sites throughout Guatemala. The largest concentration is found in Petén. This period is characterized by expanded city-building, the development of independent city-states, and contact with other Mesoamerican cultures. This lasted until around 900 AD, when the Classic Maya civilization collapsed. The Maya abandoned many of the cities of the central lowlands or died in a drought-induced famine.[11][12][page needed] Scientists debate the cause of the Classic Maya Collapse, but gaining currency is the Drought Theory discovered by physical scientists studying lake beds, ancient pollen, and other tangible evidence.[13][page needed] In 2018, 60,000 uncharted structures were revealed in northern Guatemala by archaeologists with the help of Lidar technology lasers. The project applied Lidar technology on an area of 2,100 square kilometers in the Maya Biosphere Reserve in the Petén region of Guatemala. Thanks to the new findings, archaeologists believe that 7–11 million Maya people inhabited northern Guatemala during the late classical period from 650 to 800 A.D., twice the estimated population of medieval England.[14] Lidar technology digitally removed the tree canopy to reveal ancient remains and showed that Maya cities, such as Tikal, were larger than previously assumed. The use of Lidar revealed numerous houses, palaces, elevated highways, and defensive fortifications. According to archaeologist Stephen Houston, it is one of the most overwhelming findings in over 150 years of Maya archaeology.[15][14][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23]

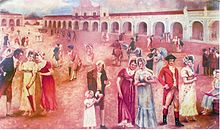

Colonial era

The colonial era of the history of Guatemala comprises the years from 1524 (when the Spaniards conquered the country) to 1821(when it became independent from Spain.[24]

Spanish conquest

Second-in-command to Hernán Cortés, Pedro de Alvarado was sent to the Guatemala highlands with 300 Spanish foot soldiers, 120 Spanish horsemen and several hundred Cholula and Tlascala auxiliaries.[25]

Alvarado entered Guatemala from Soconusco on the Pacific lowlands, headed for Xetulul Humbatz, Zapotitlán. He initially allied himself with the Cakchiquel nation to fight against their traditional rivals the K'iche'. The conquistador started his conquest in Xepau Olintepeque, defeating the K'iché's 72,000 men, led by Tecún Umán (now Guatemala's national hero). Alvarado went to Q'umarkaj, (Utatlán), the K'iche' capital, and burned it on 7 March 1524. He proceeded to Iximche, and made a base near there in Tecpan on 25 July 1524. From there he made several campaigns to other cities, including Chuitinamit, the capital of the Tzutuhils (1524); Mixco Viejo, capital of the Poqomam; and Zaculeu, capital of the Mam (1525). He was named captain general in 1527.

Having secured his position, Alvarado turned against his allies the Cakchiquels, confronting them in several battles until they were subdued in 1530. Battles with other tribes continued up to 1548, when the Q'eqchi' in Nueva Sevilla, Izabal were defeated, leaving the Spanish in complete control of the region.

Not all native tribes were subdued by bloodshed. Bartolomé de las Casas pacified the Kekchí in Alta Verapaz without violence.

After more than a century of colonization, during which mutually independent Spanish authorities in Yucatán and Guatemala made various attempts to subjugate Petén and neighboring parts of what is now Mexico. In 1697, the Spanish finally conquered Nojpetén, capital of the Itza Maya, and Zacpetén, capital of the Kowoj Maya. Due to Guatemala's location in the Pacific American coast, it became a trade node in the commerce between Asia and Latin America when it arose to become a supplementary trade route to the Manila Galleons.[26]

Era of independence from Spain

19th century

Independence and Central America civil war

In 1821, Fernando VII's power in Spain was weakened by French invasions and other conflicts, and Mexico declared the Plan de Iguala; this led Mariano Aycinena y Piñol and other criollos to demand the weak Captain General Gabino Gaínza to declare Guatemala and the rest of Central America as an independent entity. Aycinena y Piñol was one of the signatories of the Declaration of Independence of Central America from the Spanish Empire, and then lobbied strongly for Central America's annexation to the Mexican Empire of Agustín de Iturbide, due to its conservative and ecclesiastical nature.[27] remained in the legislature and was the advisor of the Governors of Guatemala in the next few years.

In October 1826, Central American Federation president Manuel José de Arce y Fagoaga dissolved the Legislature and tried to establish a Unitarian System for the region, switching from the Liberal to the Conservative party, that Aycinena led. [28] The rest of Central America did not want this system; they wanted the Aycinena family out of power altogether, and therefore, the Central American Civil War (1826–1829) started. From this war emerged the dominant figure of the Honduran general Francisco Morazán. Mariano Aycinena y Piñol -leader of the Ayicena family and the conservative power- was appointed as Governor of Guatemala on 1 March 1827 by president Manuel José Arce;[28] Aycinena regime was a dictatorship: he censored free press and any book with liberal ideology was forbidden. He also established Martial Law and the retroactive death penalty. He reinstated mandatory tithing for the secular clergy of the Catholic Church[27]

Invasion of General Morazán in 1829

Morazán and his liberal forces were fighting around San Miguel, in El Salvador beating any conservative federal forces sent by Guatemalan general Manuel Arzú from San Salvador.[29] Then, Arzú decided to take matters in his own hands and left Colonel Montúfar in charge of San Salvador and went after Morazán. After realizing that Arzu was after him, Morazán left for Honduras to look for more volunteers for his army. On 20 September, Manuel Arzá was close to the Lempa River with 500 men, when he was notified that the rest of his army had capitulated in San Salvador. Morazán then went back to El Salvador with a considerable army and General Arzú, feigning a sickness, fled to Guatemala, leaving lieutenant colonel Antonio de Aycinena in command. Aycinena and his 500 troops were going to Honduras when they were intercepted by Morazán troops in San Antonio, forcing Aycinena to concede defeat on 9 October.[30] With Aycinena defeat, there were no more conservative federal troops in El Salvador. On 23 October, general Morazán marched triumphantly in San Salvador. A few days later, he went to Ahuachapán, to organize an army to take down the conservative aristocrats led by Mariano Aycinena y Piñol in Guatemala and establish a regime favorable to the central American Federation that was the dream of the liberal criollos.[31]

Upon learning this, Aycinena y Piñol tried to negotiate with Morazán to no avail: Morazán was willing to take down the aristocrats at all costs.

After his victory in San Miguelito, Morazán's army increased in size given that a lot of voluntaries from Guatemala joined him. On 15 March, when Morazán and his army were on their way to occupy their previous positions, they were intercepted by federal troops in Las Charcas. However, Morazán had a better position and smashed the federal army. The battle field was left full of corpses, while the allies took a lot of prisoners and weaponry. the allies continued to recapture their old positions in San José Pinula and Aceituno, and place Guatemala City under siege once again.[33] General Verveer, ambassador from the King of Netherlands and Belgium before the Central American government and who was in Guatemala to negotiate the construction of a transoceanic Canal in Nicaragua, tried to mediate between the State of Guatemala and Morazán, but did not succeed. Military operations continued, with great success for the allies.

To prepare for the siege from Morazán troops, on 18 March 1829, Aycinena decreed martial law, but he was completely defeated. On 12 April 1829, Aycinena conceded defeat and he and Morazán signed an armistice pact; then, he was sent to prison, along with his Cabinet members and the Aycinena family was secluded in their mansion. Morazán, however, annulled the pact on 20 April, since his real objective was to take power away from the conservatives and the regular clergy of the Catholic Church in Guatemala, whom the Central American leaders despised since they had had the commerce and power monopoly during the Spanish Colony.[34]

Liberal rule

A member of the liberal party, Mariano Gálvez was appointed the chief of state in 1831. This was during a period of turmoil that made governing difficult. After the expulsion of the conservative leader of the Aycinena family and the regular clergy in 1829,[35] Gálvez was appointed by Francisco Morazán as Governor of Guatemala in 1831.[36] According to liberal historians Ramón Rosa[37] and Lorenzo Montúfar y Rivera,[38] Gálvez promoted major innovations in all aspects of the administration to make it less dependent on the influence of the Catholic Church. He also made public education independent of the Church, fostered science and the arts, eliminated religious festivals as holidays, founded the National Library and the National Museum, promoted respect for the laws and the rights of citizens, guaranteed freedom of the press and freedom of thought, established civil marriage and divorce, respected freedom of association, and promulgated the Livingston Code (penal code of Louisiana).[37][38] Gálvez did this against much opposition from the population who were not used to the fast pace of change; he also initiated judicial reform, reorganized municipal government and established a general head tax which severely impacted the native population.[39] However, these were all changes that the liberals wanted to implement to eliminate the political and economic power of the aristocrats and of the Catholic Church—whose regular orders were expelled in 1829 and the secular clergy was weakened by means of abolishing mandatory tithing.[40][39][a]

Among his major errors was a contract made with Michael Bennett—commercial partner of Francisco Morazán in the fine wood business—on 6 August 1834; the contract provided that the territories of Izabal, las Verapaces, Petén and Belize would be colonized within twenty years, but this proved impossible, plus made people irritated by having to deal with "heretics".[41] In February 1835 Gálvez was re-elected for a second term, during which the Asiatic cholera afflicted the country. The secular clergy that was still in the country, persuaded the uneducated people of the interior that the disease was caused by the poisoning of the springs by order of the government and turned the complaints against Gálvez into a religious war. Peasant revolts began in 1837 and under chants of "Hurray for the true religion!" and "Down with the heretics!" started growing and spreading. Gálvez asked the National Assembly to transfer the capital of the Federation from Guatemala City to San Salvador.[42]

His major opponents were Colonel and Juan de Dios Mayorga; also, José Francisco Barrundia and Pedro Molina, who had been his friends and party colleagues, came to oppose him in the later years of his government after he violently tried to repress the peasant revolt using a scorched earth approach against rural communities.[39][43]

In 1838, Antigua Guatemala, Chiquimula and Salamá withdrew recognition of his government, and in February of that year Rafael Carrera's revolutionary forces entered Guatemala City asking for the cathedral to be opened to restore order in the Catholic communities,[b] obliging Gálvez to relinquish power. Gálvez remained in the city after he lost power.

Rise of Rafael Carrera

In 1838, the liberal forces of the Honduran leader Francisco Morazán and Guatemalan José Francisco Barrundia invaded Guatemala and reached San Sur, where they executed Pascual Alvarez, Carrera's father-in-law. They impaled his head on a pike as a warning to all followers of the Guatemalan caudillo.[44] On learning this, Carrera and his wife Petrona—who had come to confront Morazán as soon as they learned of the invasion and were in Mataquescuintla—swore they would never forgive Morazán even in his grave; they felt it impossible to respect anyone who would not avenge family members.[45]

After sending several envoys, whom Carrera would not receive—especially Barrundia whom Carrera did not want to murder in cold blood – Morazán began a scorched earth offensively, destroying villages in his path and stripping them of their few assets. The Carrera forces had to hide in the mountains.[46] Believing that Carrera was totally defeated, Morazán and Barrundia marched on to Guatemala City, where they were welcomed as saviors by the state governor Pedro Valenzuela and members of the conservative Aycinena Clan, who proposed to sponsor one of the liberal battalions, while Valenzuela and Barrundia gave Morazán all the Guatemalan resources needed to solve any financial problem he had.[47] The criollos of both parties celebrated until dawn that they finally had a criollo caudillo like Morazán, who was able to crush the peasant rebellion.[48]

Morazán used the proceeds to support Los Altos and then replaced Valenzuela by Mariano Rivera Paz, member of the Aycinena clan, although he did not return to that clan any property confiscated in 1829; in revenge, Juan José de Aycinena y Piñol voted for the dissolution of the Central American Federation in San Salvador a little later, forcing Morazán to return to El Salvador to fight to save his federal mandate. Along the way, Morazán increased repression in eastern Guatemala, as punishment for helping Carrera.[49] Knowing that Morazán had gone to El Salvador, Carrera tried to take Salamá with the small force that remained but was defeated, losing his brother Laureano in the combat. With just a few men left, he managed to escape, badly wounded, to Sanarate.[50] After recovering to some extent, he attacked a detachment in Jutiapa and managed to get a small amount of booty which he handed to the volunteers who accompanied him and prepared to attack Petapa—near Guatemala City—where he was victorious, though with heavy casualties.[51]

In September of that year, he attempted an assault on the capital of Guatemala, but the liberal general Carlos Salazar Castro defeated him in the fields of Villa Nueva and Carrera had to retreat.[52] After an unsuccessful attempt to take the Quetzaltenango, Carrera was surrounded and wounded, and he had to capitulate to the Mexican General Agustin Guzman, who had been in Quetzaltenango since the time of Vicente Filísola's arrival in 1823. Morazán had the opportunity to shoot Carrera, but did not because he needed the support of the Guatemalan peasants to counter the attacks of Francisco Ferrera in El Salvador; instead, Morazán left Carrera in charge of a small fort in Mita, and without any weapons. Knowing that Morazán was going to attack El Salvador, Francisco Ferrera gave arms and ammunition to Carrera and convinced him to attack Guatemala City.[53]

Meanwhile, despite insistent advice to definitely crush Carrera and his forces, Salazar tried to negotiate with him diplomatically; he even went as far as to show that he neither feared nor distrusted Carrera by removing the fortifications of the Guatemalan capital, in place in since the battle of Villa Nueva.[52] Taking advantage of Salazar's good faith and Ferrera's weapons, Carrera took Guatemala City by surprise on 13 April 1839; Castro Salazar, Mariano Gálvez and Barrundia fled before the arrival of Carrera's militiamen. Salazar, in his nightshirt, vaulted roofs of neighboring houses and sought refuge;[54][55] reaching the border disguised as a peasant.[54][55] With Salazar gone, Carrera reinstated Rivera Paz as head of state of Guatemala.

Invasion and absorption of Los Altos

On 2 April 1838, in the city of Quetzaltenango, a secessionist group founded the independent State of Los Altos which sought independence from Guatemala. The most important members of the Liberal Party of Guatemala and liberal enemies of the conservative regime moved to Los Altos, leaving their exile in El Salvador.[56] The liberals in Los Altos began severely criticizing the Conservative government of Rivera Paz; they had their own newspaper—El Popular—which contributed to the harsh criticism.[56]

Los Altos was the region with the main production and economic activity of the former state of Guatemala. without Los Altos, conservatives lost much of the resources that had given Guatemala hegemony in Central America.[56] Then, the government of Guatemala tried to reach to a peaceful solution, but altenses,[c] protected by the recognition of the Central American Federation Congress, did not accept; Guatemala's government then resorted to force, sending Carrera as commanding general of the Army to subdue Los Altos.

Carrera defeated General Agustin Guzman when the former Mexican officer tried to ambush him and then went on to Quetzaltenango, where he imposed a harsh and hostile conservative regime instead of the liberals. Calling all council members, he told them flatly that he was behaving leniently towards them as it was the first time they had challenged him, but sternly warned them that there would be no mercy if there was a second time.[57] Finally, Guzmán, and the head of state of Los Altos, Marcelo Molina, were sent to the capital of Guatemala, where they were displayed as trophies of war during a triumphant parade on 17 February 1840; in the case of Guzman, shackled, still with bleeding wounds, and riding a mule.[56]

On 18 March 1840, liberal caudillo Morazán invaded Guatemala with 1500 soldiers to avenge the insult done in Los Altos. Fearing that such action would end with liberal efforts to hold together the Central American Federation, Guatemala had a cordon of guards from the border with El Salvador; without a telegraph service, men ran carrying last-minute messages.[58] With the information from these messengers, Carrera hatched a plan of defense leaving his brother Sotero in charge of troops who presented only slight resistance in the city.[59] Carrera pretended to flee and led his ragtag army to the heights of Aceituno, with few men, few rifles and two old cannons. The city was at the mercy of the army of Morazán, with bells of the twenty churches ringing for divine assistance.[58]

Once Morazán reached the capital, he took it very easily and freed Guzman, who immediately left for Quetzaltenango to give the news that Carrera was defeated;[59] Carrera then, taking advantage of what his enemies believed, applied a strategy of concentrating fire on the Central Park of the city and also employed surprise attack tactics which caused heavy casualties to the army of Morazán, finally forcing the survivors to fight for their lives.[d][60] Morazán's soldiers lost the initiative and their previous numerical superiority. Furthermore, in unfamiliar surroundings in the city, they had to fight, carry their dead and care for their wounded while resentful and tired from the long march from El Salvador to Guatemala.[60]

Carrera, by then an experienced military man, was able to defeat Morazán thoroughly. The disaster for the liberal general was complete: aided by Angel Molina—son of Guatemalan Liberal leader Pedro Molina Mazariegos—who knew the streets of the city, had to flee with his favorite men, disguised, shouting "Long live Carrera!" through the ravine of "El Incienso" to El Salvador.[58] In his absence, Morazán had been supplanted as Head of State of his country, and had to embark for exile in Peru.[60] In Guatemala, survivors from his troops were shot without mercy, while Carrera was out in unsuccessful pursuit of Morazán. This engagement sealed the status of Carrera and marked the decline of Morazán,[58] and forced the conservative Aycinena clan criollos to negotiate with Carrera and his peasant revolutionary supporters.[61]

Guzmán, who was freed by Morazán when the latter had seemingly defeated Carrera in Guatemala City, had gone back to Quetzaltenango to bring the good news. The city liberal criollo leaders rapidly reinstated the Los Altos State and celebrated Morazán's victory. However, as soon as Carrera and the newly reinstated Mariano Rivera Paz heard the news, Carrera went back to Quetzaltenango with his volunteer army to regain control of the rebel liberal state once and for all.[62] On 2 April 1840, after entering the city, Carrera told the citizens that he had already warned them after he defeated them earlier that year. Then, he ordered the majority of the liberal city hall officials from Los Altos to be shot. Carrera then forcibly annexed Quetzaltenango and much of Los Altos back into conservative Guatemala.[63]

After the violent and bloody reinstatement of the State of Los Altos by Carrera in April 1840, Luis Batres Juarros—conservative member of the Aycinena Clan, then secretary general of the Guatemalan government of recently reinstated Mariano Rivera Paz—obtained from the vicar Larrazabal authorization to dismantle the regionalist Church. Serving priests of Quetzaltenango—capital of the would-be-state of Los Altos, Urban Ugarte and his coadjutor, José Maria Aguilar, were removed from their parish and likewise the priests of the parishes of San Martin Jilotepeque and San Lucas Tolimán. Larrazabal ordered the priests Fernando Antonio Dávila, Mariano Navarrete and Jose Ignacio Iturrioz to cover the parishes of Quetzaltenango, San Martin Jilotepeque and San Lucas Toliman, respectively.[63]

The liberal criollos' defeat and execution in Quetzaltenango enhanced Carrera's status with the native population of the area, whom he respected and protected.[61]

In 1840, Belgium began to act as an external source of support for Carrera's independence movement, in an effort to exert influence in Central America. The Compagnie belge de colonisation (Belgian Colonization Company), commissioned by Belgian King Leopold I, became the administrator of Santo Tomas de Castilla[64] replacing the failed British Eastern Coast of Central America Commercial and Agricultural Company.[64] Even though the colony eventually crumbled, Belgium continued to support Carrera in the mid-19th century, although Britain continued to be the main business and political partner to Carrera.[65]

Rafael Carrera was elected Guatemalan Governor in 1844. On 21 March 1847, Guatemala declared itself an independent republic and Carrera became its first president.

During the first term as president, Carrera had brought the country back from extreme conservatism to a traditional moderation; in 1848, the liberals were able to drive him from office, after the country had been in turmoil for several months.[66][67] Carrera resigned of his own free will and left for México. The new liberal regime allied itself with the Aycinena family and swiftly passed a law ordering Carrera's execution if he dared to return to Guatemalan soil.[66] The liberal criollos from Quetzaltenango were led by general Agustín Guzmán who occupied the city after Corregidor general Mariano Paredes was called to Guatemala City to take over the Presidential office.[68] They declared on 26 August 1848 that Los Altos was an independent state once again. The new state had the support of Vasconcelos' regime in El Salvador and the rebel guerrilla army of Vicente and Serapio Cruz who were sworn enemies of Carrera.[69] The interim government was led by Guzmán himself and had Florencio Molina and the priest Fernando Davila as his Cabinet members.[70] On 5 September 1848, the criollos altenses chose a formal government led by Fernando Antonio Martínez.

In the meantime, Carrera decided to return to Guatemala and did so entering by Huehuetenango, where he met with the native leaders and told them that they must remain united to prevail; the leaders agreed and slowly the segregated native communities started developing a new Indian identity under Carrera's leadership.[71] In the meantime, in the eastern part of Guatemala, the Jalapa region became increasingly dangerous; former president Mariano Rivera Paz and rebel leader Vicente Cruz were both murdered there after trying to take over the Corregidor office in 1849.[71]

When Carrera arrived to Chiantla in Huehuetenango, he received two altenses emissaries who told him that their soldiers were not going to fight his forces because that would lead to a native revolt, much like that of 1840; their only request from Carrera was to keep the natives under control.[71] The altenses did not comply, and led by Guzmán and his forces, they started chasing Carrera; the caudillo hid helped by his native allies and remained under their protection when the forces of Miguel García Granados—who arrived from Guatemala City were looking for him.[71]

On learning that officer José Víctor Zavala had been appointed as Corregidor in Suchitepéquez Department, Carrera and his hundred jacalteco bodyguards crossed a dangerous jungle infested with jaguars to meet his former friend. When they met, Zavala not only did not capture him, but agreed to serve under his orders, thus sending a strong message to both liberal and conservatives in Guatemala City that they would have to negotiate with Carrera or battle on two fronts—Quetzaltenango and Jalapa.[72] Carrera went back to the Quetzaltenango area, while Zavala remained in Suchitepéquez as a tactical maneuver.[40] Carrera received a visit from a Cabinet member of Paredes and told him that he had control of the native population and that he assured Paredes that he would keep them appeased.[72] When the emissary returned to Guatemala City, he told the president everything Carrera said, and added that the native forces were formidable.[73]

Guzmán went to Antigua Guatemala to meet with another group of Paredes emissaries; they agreed that Los Altos would rejoin Guatemala, and that the latter would help Guzmán defeat his hated enemy and also build a port on the Pacific Ocean.[73] Guzmán was sure of victory this time, but his plan evaporated when, in his absence, Carrera and his native allies had occupied Quetzaltenango; Carrera appointed Ignacio Yrigoyen as Corregidor and convinced him that he should work with the k'iche', mam, q'anjobal and mam leaders to keep the region under control.[74] On his way out, Yrigoyen murmured to a friend: Now he is the King of the Indians, indeed![74]

Guzmán then left for Jalapa, where he struck a deal with the rebels, while Luis Batres Juarros convinced President Paredes to deal with Carrera. Back in Guatemala City within a few months, Carrera was commander-in-chief, backed by military and political support of the Indian communities from the densely populated western highlands.[75] During the first presidency from 1844 to 1848, he brought the country back from excessive conservatism to a moderate regime, and–with the advice of Juan José de Aycinena y Piñol and Pedro de Aycinena—restored relations with the Church in Rome with a Concordat ratified in 1854.[76] He also kept peace between natives and criollos, with the latter fearing a rising like the one that was taking place in Yucatán at the time.[77]

Caste War of Yucatán

In Yucatán, then an independent republic north of Guatemala, a war started between the natives and criollo people; this war seemed rooted in the defense of communal lands against the expansion of private ownership, which was accentuated by the boom in the production of henequen, which was an important industrial fiber used to make rope. After discovering the value of the plant, the wealthier Yucateco criollos started plantations, beginning in 1833, to cultivate it on a large scale; not long after the henequen boom, a boom in sugar production led to more wealth. The sugar and henequen plantations encroached on native communal land, and native workers recruited to work on the plantations were mistreated and underpaid.[77]

However, rebel leaders in their correspondence with British Honduras were more often inclined to cite taxation as the immediate cause of the war; Jacinto Pat, for example, wrote in 1848 that "what we want is liberty and not oppression, because before we were subjugated with the many contributions and taxes that they imposed on us."[78] Pac's companion, Cecilio Chi added in 1849, that promises made by the rebel Santiago Imán, that he was "liberating the Indians from the payment of contributions" as a reason for resisting the central government, but in fact he continued levying them.[79]

In June 1847, Méndez learned that a large force of armed natives and supplies had gathered at the Culumpich, a property owned by Jacinto Pat, the Maya batab (leader), near Valladolid. Fearing revolt, Mendez arrested Manuel Antonio Ay, the principal Maya leader of Chichimilá, accused of planning a revolt, and executed him at the town square of Valladolid. Furthermore, Méndez searching for other insurgents burned the town of Tepich and repressed its residents. In the following months, several Maya towns were sacked and many people arbitrarily killed. In his letter of 1849, Cecilio Chi noted that Santiago Mendez had come to "put every Indian, big and little, to death" but that the Maya had responded to some degree, in kind, writing "it has pleased God and good fortune that a much greater portion of them than of the Indians .[80]

Cecilio Chi, the native leader of Tepich, along with Jacinto Pat attacked Tepich on 30 July 1847, in reaction to the indiscriminate massacre of Mayas, ordered that all the non-Maya population be killed. By spring of 1848, the Maya forces had taken over most of the Yucatán, with the exception of the walled cities of Campeche and Mérida and the south-west coast, with Yucatecan troops holding the road from Mérida to the port of Sisal. The Yucatecan governor Miguel Barbachano had prepared a decree for the evacuation of Mérida, but was apparently delayed in publishing it by the lack of suitable paper in the besieged capital. The decree became unnecessary when the republican troops suddenly broke the siege and took the offensive with major advances.[81]

Governor Barbachano sought allies anywhere he could find them, in Cuba (for Spain), Jamaica (for the United Kingdom) and the United States, but none of these foreign powers would intervene, although the matter was taken seriously enough in the United States to be debated in Congress. Subsequently, therefore, he turned to Mexico, and accepted a return to Mexican authority. Yucatán was officially reunited with Mexico on 17 August 1848. Yucateco forces rallied, aided by fresh guns, money, and troops from Mexico, and pushed back the natives from more than half of the state.[82]

By 1850 the natives occupied two distinct regions in the southeast and they were inspired to continue the struggle by the apparition of the "Talking Cross". This apparition, believed to be a way in which God communicated with the Maya, dictated that the War continue. Chan Santa Cruz, or Small Holy Cross became the religious and political center of the Maya resistance and the rebellion came to be infused with religious significance. Chan Santa Cruz also became the name of the largest of the independent Maya states, as well as the name of the capital city which is now the city of Felipe Carrillo Puerto, Quintana Roo. The followers of the Cross were known as the "Cruzob".

The government of Yucatán first declared the war over in 1855, but hopes for peace were premature. There were regular skirmishes, and occasional deadly major assaults into each other's territory, by both sides. The United Kingdom recognized the Chan Santa Cruz Maya as a "de facto" independent nation, in part because of the major trade between Chan Santa Cruz and British Honduras.{{[83]}}

Battle of La Arada

After Carrera returned from exile in 1849, Vasconcelos granted asylum to the Guatemalan liberals, who harassed the Guatemalan government in several different forms: José Francisco Barrundia did it through a liberal newspaper established with that specific goal; Vasconcelos gave support during a whole year to a rebel faction "La Montaña", in eastern Guatemala, providing and distributing money and weapons. By late 1850, Vasconcelos was getting impatient at the slow progress of the war with Guatemala and decided to plan an open attack. Under that circumstance, the Salvadorean head of state started a campaign against the conservative Guatemalan regime, inviting Honduras and Nicaragua to participate in the alliance; only the Honduran government led by Juan Lindo accepted.[66]

Meanwhile, in Guatemala, where the invasion plans were perfectly well known, President Mariano Paredes started taking precautions to face the situation, while the Guatemalan Archbishop, Francisco de Paula García Peláez, ordered peace prayers in the archdiocese.[e]

On 4 January 1851, Doroteo Vasconcelos and Juan Lindo met in Ocotepeque, Honduras, where they signed an alliance against Guatemala. The Salvadorean army had 4,000 men, properly trained and armed and supported by artillery; the Honduran army numbered 2,000 men. The coalition army was stationed in Metapán, El Salvador, due to its proximity with both the Guatemalan and Honduran borders.[66][84]

On 28 January 1851, Vasconcelos sent a letter to the Guatemalan Ministry of Foreign Relations, in which he demanded that the Guatemalan president relinquish power, so that the alliance could designate a new head of state loyal to the liberals and that Carrera be exiled, escorted to any of the Guatemalan southern ports by a Salvadorean regiment.[85] The Guatemalan government did not accept the terms and the Allied army entered Guatemalan territory at three different places. On 29 January, a 500-man contingent entered through Piñuelas, Agua Blanca and Jutiapa, led by General Vicente Baquero, but the majority of the invading force marched from Metapán. The Allied army was composed of 4,500 men led by Vasconcelos, as Commander in Chief. Other commanders were the generals José Santos Guardiola, Ramón Belloso, José Trinidad Cabañas, and Gerardo Barrios. Guatemala was able to recruit 2,000 men, led by Lieutenant General Carrera as Commander in Chief, with several colonels.

Carrera's strategy was to feign a retreat, forcing the enemy forces to follow the "retreating" troops to a place he had previously chosen; on 1 February 1851, both armies were facing each other with only the San José river between them. Carrera had fortified the foothills of La Arada, its summit about 50 metres (160 ft) above the level of the river. A meadow 300 metres (1,000 ft) deep lay between the hill and the river, and boarding the meadow was a sugar cane plantation. Carrera divided his army in three sections: the left wing was led by Cerna and Solares; the right wing led by Bolaños. He personally led the central battalion, where he placed his artillery. Five hundred men stayed in Chiquimula to defend the city and to aid in a possible retreat, leaving only 1,500 Guatemalans against an enemy of 4,500.

The battle began at 8:30 am, when Allied troops initiated an attack at three different points, with an intense fire opened by both armies. The first Allied attack was repelled by the defenders of the foothill; during the second attack, the Allied troops were able to take the first line of trenches. They were subsequently expelled. During the third attack, the Allied force advanced to a point where it was impossible to distinguish between Guatemalan and Allied troops. Then, the fight became a melée, while the Guatemalan artillery severely punished the invaders. At the height of the battle when the Guatemalans faced an uncertain fate, Carrera ordered that sugar cane plantation around the meadow to be set on fire. The invading army was now surrounded: to the front, they faced the furious Guatemalan firepower, to the flanks, a huge blaze and to the rear, the river, all of which made retreat very difficult. The central division of the Allied force panicked and started a disorderly retreat. Soon, all of the Allied troops started retreating.

The 500 men of the rearguard pursued what was left of the Allied army, which desperately fled for the borders of their respective countries. The final count of the Allied losses were 528 dead, 200 prisoners, 1,000 rifles, 13,000 rounds of ammunition, many pack animals and baggage, 11 drums and seven artillery pieces. Vasconcelos sought refuge in El Salvador, while two Generals mounted on the same horse were seen crossing the Honduran border. Carrera regrouped his army and crossed the Salvadorean border, occupying Santa Ana, before he received orders from the Guatemalan President, Mariano Paredes, to return to Guatemala, since the Allies were requesting a cease-fire and a peace treaty.[86]

Concordat of 1854

The Concordat of 1854 was an international treaty between Carrera and the Holy See, signed in 1852 and ratified by both parties in 1854. Through this, Guatemala gave the education of Guatemalan people to regular orders of the Catholic Church, committed to respect ecclesiastical property and monasteries, imposed mandatory tithing and allowed the bishops to censor what was published in the country; in return, Guatemala received dispensations for the members of the army, allowed those who had acquired the properties that the liberals had expropriated from the Church in 1829 to keep those properties, received the taxes generated by the properties of the Church, and had the right to judge certain crimes committed by clergy under Guatemalan law.[87] The concordat was designed by Juan José de Aycinena y Piñol and not only reestablished but reinforced the relationship between Church and State in Guatemala. It was in force until the fall of the conservative government of Field Marshal Vicente Cerna y Cerna.

In 1854, by initiative of Manuel Francisco Pavón Aycinena, Carrera was declared "supreme and perpetual leader of the nation" for life, with the power to choose his successor. He was in that position until he died on 14 April 1865. While he pursued some measures to set up a foundation for economic prosperity to please the conservative landowners, military challenges at home and in a three-year war with Honduras, El Salvador, and Nicaragua dominated his presidency. His rivalry with Gerardo Barrios, President of El Salvador, resulted in open war in 1863.

At Coatepeque the Guatemalans suffered a severe defeat, which was followed by a truce. Honduras joined with El Salvador, and Nicaragua and Costa Rica with Guatemala. The contest was finally settled in favor of Carrera, who besieged and occupied San Salvador, and dominated Honduras and Nicaragua. He continued to act in concert with the Clerical Party, and tried to maintain friendly relations with the European governments. Before his death, Carrera nominated his friend and loyal soldier, Army Marshall Vicente Cerna y Cerna, as his successor.

Wyke-Aycinena treaty: Limits convention about Belize

The Belize region in the Yucatán Peninsula was never occupied by either Spain or Guatemala. Spain made some exploratory expeditions in the 16th century that served as its basis to claim the area.[88] Guatemala simply inherited that argument to claim the territory, even though it never sent an expedition to the area after independence from Spain, due to the ensuing Central American civil war that lasted until 1860.[88]

The British had had a small settlement there since the middle of the 17th century, mainly as buccaneers' quarters and then for wood production. The settlements were never recognized as British colonies although they were somewhat under the jurisdiction of the British government in Jamaica.[88] In the 18th century, Belize became the main smuggling center for Central America, even though the British accepted Spain's sovereignty over the region via treaties signed in 1783 and 1786, in exchange for a ceasefire and the authorization for British subjects to work in the forests of Belize.[88]

After 1821, Belize became the leading edge of Britain's commercial entrance in the isthmus. British commercial brokers established themselves and began prosperous commercial routes plying the Caribbean harbors of Guatemala, Honduras and Nicaragua.[88]

When Carrera came to power in 1840 he stopped the complaints over Belize and established a Guatemalan consulate in the region to oversee Guatemalan interests.[88] Belize commerce boomed in the region until 1855, when the Colombians built a transoceanic railway that allowed commerce to flow more efficiently between the oceans. Thereafter Belize's commercial importance declined.[88] When the Caste War of Yucatán began in the Yucatán Peninsula the Belize and Guatemala representatives were on high alert; Yucatán refugees fled into both Guatemala and Belize and Belize's superintendent came to fear that Carrera–given his strong alliance with Guatemalan natives–could support the native uprisings.[88]

In the 1850s, the British employed goodwill to settle the territorial differences with Central American countries. They: withdrew from the Mosquito Coast in Nicaragua and began talks that would end by restoring the territory to Nicaragua in 1894: returned the Bay Islands to Honduras and negotiated with the American filibuster William Walker in an effort to prevent him from conducting an invasion of Honduras.[89][90][91] They signed a treaty with Guatemala regarding Belize's borders, which has been referred to by some Guatemalans as the worst mistake made by Rafael Carrera.[89]

Pedro de Aycinena y Piñol, as Foreign Secretary, made an extra effort to keep good relations with the Crown. In 1859, Walker again threatened Central America; in order to get the weapons needed to face the filibuster, Carrera's regime had to come to terms about Belize with the British.[90] On 30 April 1859, the Wyke-Aycinena treaty was signed, between the British and Guatemalan representatives.[92] The treaty had two parts:

- The first six articles clearly defined the Guatemala-Belize border: Guatemala acknowledged Britain's sovereignty over Belize.[89]

- The seventh article was about the construction of a road between Guatemala City and the Caribbean coast, which would be of mutual benefit, as Belize needed a way to communicate with the Pacific coast in order to return to commercial relevance; Guatemala needed a road to improve communication with its Atlantic coast. However, the road was never built; first because Guatemalans and Belizeans could not agree on the exact location for the road, and later because the conservatives lost power in Guatemala in 1871, and the liberal government declared the treaty void.[93]

Among those who signed the treaty was José Milla y Vidaurre, who worked with Aycinena in the Foreign Ministry at the time.[66] Carrera ratified the treaty on 1 May 1859, while Charles Lennox Wyke, British consul in Guatemala, traveled to Great Britain and got royal approval on 26 September 1859.[93] American consul Beverly Clarke objected with some liberal representatives, but the issue was settled.[93]

As of 1850, it was estimated that Guatemala had a population of 600,000.[94][95]

Guatemala's "Liberal Revolution" came in 1871 under the leadership of Justo Rufino Barrios, who worked to modernize the country, improve trade and introduce new crops and manufacturing. During this era coffee became an important crop for Guatemala.[96] Barrios had ambitions of reuniting Central America and took the country to war in an unsuccessful attempt to attain it, losing his life on the battlefield in 1885 to forces in El Salvador.

Justo Rufino Barrios government

The Conservative government in Honduras gave military backing to a group of Guatemalan Conservatives wishing to take back the government, so Barrios declared war on the Honduran government. At the same time, Barrios, together with President Luis Bogran of Honduras, declared an intention to reunify the old United Provinces of Central America.

During his time in office, Barrios continued with the liberal reforms initiated by García Granados, but he was more aggressive implementing them. A summary of his reforms is:[97]

- Definitive separation between Church and State: he expelled the regular clergy such as Morazán had done in 1829 and confiscated their properties.

Regular order Coat of arms Clergy type Confiscated properties Order of Preachers

Regular - Monasteries

- Large extensions of farmland

- Sugar mills

- Indian doctrines[f]

Mercedarians

Regular - Monasteries

- Large extensions of farmland

- Sugar mills

- Indian doctrines

Society of Jesus

Regular The Jesuits had been expelled from the Spanish colonies back in 1765 and did not return to Guatemala until 1852. By 1871, they did not have major possessions. Recoletos

Regular - Monasterires

Conceptionists

Regular - Monasteries

- Large extensions of farmland

Archdiocese of Guatemala Secular School and Trentin Seminar of Nuestra Señora de la Asunción Congregation of the Oratory Secular - Church building and housing in Guatemala City were obliterated by presidential order.[98]

- Forbid mandatory tithing to weaken secular clergy members and the archbishop.

- Established civil marriage as the only official one in the country

- Secular cemeteries

- Civil records superseded religious ones

- Established secular education across the country

- Established free and mandatory elementary schools

- Closed the Pontifical University of San Carlos and in its place created the secular National University.[97]

Barrios had a National Congress totally pledge to his will, and therefore he was able to create a new constitution in 1879, which allowed him to be reelected as president for another six-year term.[97]

He also was intolerant with his political opponents, forcing a lot of them to flee the country and building the infamous Guatemalan Central penitentiary where he had numerous people incarcerated and tortured.[99]

During Barrios' tenure, the "indian land" that the conservative regime of Rafael Carrera had so strongly defended was confiscated and distributed among those officers who had helped him during the Liberal Revolution in 1871.[100] Decree # 170 (a.k.a. Census redemption decree) made it easy to confiscate those lands in favor of the army officers and the German settlers in Verapaz as it allowed to publicly sell those common Indian lots.[101] Therefore, the fundamental characteristic of the productive system during Barrios regime was the accumulation of large extension of land among few owners[102] and a sort of "farmland servitude", based on the exploitation of the native day laborers.[101]

In order to make sure that there was a steady supply of day laborers for the coffee plantations, which required a lot of them, Barrios government decreed the Day Laborer regulations, labor legislation that placed the entire native population at the disposition of the new and traditional Guatemalan landlords, except the regular clergy, who were eventually expelled form the country and saw their properties confiscated.[100] This decree set the following for the native Guatemalans:

- Were forced by law to work on farms when the owners of those required them, without any regard for where the native towns were located.

- Were under control of local authorities, who were in charge to make sure that day laborer batches were sent to all the farms that required them.

- Were subject to habilitation: a type of forced advanced pay, which buried the day laborer in debt and then made it legal for the landlords to keep them in their land for as long as they wanted.

- Created the day laborer booklet: a document that proved that a day laborer had no debts to his employer. Without this document, any day laborer was at the mercy of the local authorities and the landlords.[103]

In 1879, a constitution was ratified for Guatemala (the Republic's first as an independent nation, as the old Conservador regime had ruled by decree). In 1880, Barrios was reelected President for a six-year term. Barrios unsuccessfully attempted to get the United States to mediate the disputed boundary between Guatemala and Mexico.

Government of Manuel Lisandro Barillas

General Manuel Lisandro Barillas Bercián was able to become interim president of Guatemala after the death of President Justo Rufino Barrios in the Batalla of Chalchuapa in El Salvador in April 1885 and after the resignation of first designate Alejandro Manuel Sinibaldi Castro, by means of a clever scam: he went to the General Cemetery when Barrios was being laid to rest and told the Congress president: "please prepare room and board for the 5,000 troops that I have waiting for my orders in Mixco". The congress president was scared of this, and declared Barillas interim president on the spot. By the time he realized that it was all a lie, it was too late to change anything.[66]

Instead of calling for elections, as he should have, Barillas Bercián was able to be declared President on 16 March 1886 and remained in office until 1892.[66]

During the government of general Barillas Bercián, the Carrera theater was remodeled to celebrate the Discovery of America fourth centennial; the Italian community in Guatemala donated a statue of Christopher Columbus -Cristóbal Colón, in Spanish- which was placed next to the theater. Since then, the place was called "Colón Theater".[104]

In 1892, Barillas called for elections as he wanted to take care of his personal business; it was the first election in Guatemala that allowed the candidates to make propaganda in the local newspapers.[105]

Barillas Bercian was unique among liberal presidents of Guatemala between 1871 and 1944: he handed over power to his successor peacefully. When election time approached, he sent for the three Liberal candidates to ask them what their government plan would be.[106] Happy with what he heard from general Reyna Barrios,[106] Barillas made sure that a huge column of Quetzaltenango and Totonicapán Indigenous people came down from the mountains to vote for general Reyna Barrios. Reyna was elected president. [107] As to not to offend the losing candidates, Barillas gave them checks to cover the costs of their presidential campaigns. Reyna Barrios went on to become president on 15 March 1892.[108]

20th century

In the 1890s, the United States began to implement the Monroe Doctrine, pushing out European colonial powers and establishing U.S. hegemony over resources and labor in Latin American nations. The dictators that ruled Guatemala during the late 19th and early 20th century were generally very accommodating to U.S. business and political interests; thus, unlike other Latin American nations such as Haiti, Nicaragua and Cuba the U.S. did not have to use overt military force to maintain dominance in Guatemala. The Guatemalan military/police worked closely with the U.S. military and State Department to secure U.S. interests. The Guatemalan government exempted several U.S. corporations from paying taxes, especially the United Fruit Company, privatized and sold off publicly owned utilities, and gave away huge swaths of public land.[109]

Manuel Estrada Cabrera regime (1898–1920)

After the assassination of general José María Reina Barrios on 8 February 1898, the Guatemalan cabinet called an emergency meeting to appoint a new successor, but declined to invite Estrada Cabrera to the meeting, even though he was the First Designated to the Presidency. There are two versions on how he was able to get the Presidency: r

a) Estrada Cabrera entered "with pistol drawn" to assert his entitlement to the presidency [110] or (b) Estrada Cabrera showed up unarmed to the meeting and demanded to be given the presidency as he was the First Designated".[111]

The first Guatemalan head of state taken from civilian life in over 50 years, Estrada Cabrera overcame resistance to his regime by August 1898 and called for September elections, which he won handily.[112] At that time, Estrada Cabrera was 44 years old; he was stocky, of medium height, dark, and broad-shouldered. The mustache gave him a plebeian appearance. He had dark eyes, a metallic voice and a rather sullen, brooding mien. At the same time, he had already showed courage and character on the night Reina Barrios died, when he stood in front of the ministers meeting in the Government Palace to choose a success.or, and said: Gentlemen, let me please sign this decree. As First Designated, you must hand me the Presidency. "His first decree was a general amnesty, and the second was to reopen all the elementary schools closed by Reyna Barrios,[clarification needed] both administrative and political measures to gain the public support. Estrada Cabrera was almost unknown in the political circles of the capital and the nature of his government and his intentions were unknown.[113]

In 1898, the Legislature convened to elect President Estrada Cabrera, who triumphed thanks to the large number of soldiers and policemen who went to vote in civilian clothing and to the large number of illiterate families that they brought with them to the polls. Also, the effective propaganda that was written in the official newspaper "the Liberal Idea '.[clarification needed] The latter was run by the poet Joaquin Mendez and among the drafters were Enrique Gómez Carrillo, -a famous writer who had just returned to Guatemala from Paris, and who had confidence that Estrada Cabrera was the president that Guatemala needed, Rafael Spinola, Máximo Soto Hall and Juan Manuel Mendoza, who later would be Gómez Carrillo's biographer, and others. Gómez Carrillo received as a reward for his work as political propagandist the appointment as General Consul in Paris, with 250 gold pesos monthly salary and immediately went back to Europe [114]

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=History_of_Guatemala

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk