A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| |

| Composition | Elementary particle |

|---|---|

| Statistics | Bosonic |

| Symbol | H0 |

| Theorised | R. Brout, F. Englert, P. Higgs, G. S. Guralnik, C. R. Hagen, and T. W. B. Kibble (1964) |

| Discovered | Large Hadron Collider (2011–2013) |

| Mass | 125.11 ± 0.11 GeV/c2[1] |

| Mean lifetime | 1.56×10−22 s[b] (predicted) 1.2 ~ 4.6 × 10−22 s (tentatively measured at 3.2 sigma (1 in 1000) significance)[3][4] |

| Decays into |

|

| Electric charge | 0 e |

| Colour charge | 0 |

| Spin | 0 ħ[7][8] |

| Weak isospin | −1/2 |

| Weak hypercharge | +1 |

| Parity | +1[7][8] |

The Higgs boson, sometimes called the Higgs particle,[9][10] is an elementary particle in the Standard Model of particle physics produced by the quantum excitation of the Higgs field,[11][12] one of the fields in particle physics theory.[12] In the Standard Model, the Higgs particle is a massive scalar boson with zero spin, even (positive) parity, no electric charge, and no colour charge that couples to (interacts with) mass.[13] It is also very unstable, decaying into other particles almost immediately upon generation.

The Higgs field is a scalar field with two neutral and two electrically charged components that form a complex doublet of the weak isospin SU(2) symmetry. Its "Sombrero potential" leads it to take a nonzero value everywhere (including otherwise empty space), which breaks the weak isospin symmetry of the electroweak interaction and, via the Higgs mechanism, gives a rest mass to all massive elementary particles of the Standard Model, including the Higgs boson itself.

Both the field and the boson are named after physicist Peter Higgs, who in 1964, along with five other scientists in three teams, proposed the Higgs mechanism, a way for some particles to acquire mass. (All fundamental particles known at the time[c] should be massless at very high energies, but fully explaining how some particles gain mass at lower energies had been extremely difficult.) If these ideas were correct, a particle known as a scalar boson should also exist (with certain properties). This particle was called the Higgs boson and could be used to test whether the Higgs field was the correct explanation.

After a 40-year search, a subatomic particle with the expected properties was discovered in 2012 by the ATLAS and CMS experiments at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN near Geneva, Switzerland. The new particle was subsequently confirmed to match the expected properties of a Higgs boson. Physicists from two of the three teams, Peter Higgs and François Englert, were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2013 for their theoretical predictions. Although Higgs's name has come to be associated with this theory, several researchers between about 1960 and 1972 independently developed different parts of it.

In the media, the Higgs boson is sometimes called the "God particle" after the 1993 book The God Particle by Nobel Laureate Leon Lederman.[14] The name has been criticised by physicists,[15][16] including Higgs.[17]

Introduction

| Standard Model of particle physics |

|---|

|

Standard Model

Physicists explain the fundamental particles and forces of our universe in terms of the Standard Model – a widely accepted framework based on quantum field theory that predicts almost all known particles and forces aside from gravity with great accuracy. (A separate theory, general relativity, is used for gravity.) In the Standard Model, the particles and forces in nature (aside from gravity) arise from properties of quantum fields known as gauge invariance and symmetries. Forces in the Standard Model are transmitted by particles known as gauge bosons.[18][19]

Gauge invariant theories and symmetries

- "It is only slightly overstating the case to say that physics is the study of symmetry" – Philip Anderson, Nobel Prize Physics[20]

Gauge invariant theories are theories which have a useful feature; some kinds of changes to the value of certain items do not make any difference to the outcomes or the measurements we make. An example: changing voltages in an electromagnet by +100 volts does not cause any change to the magnetic field it produces. Similarly, measuring the speed of light in vacuum seems to give the identical result, whatever the location in time and space, and whatever the local gravitational field.

In these kinds of theories, the gauge is an item whose value we can change. The fact that some changes leave the results we measure unchanged means it is a gauge invariant theory, and symmetries are the specific kinds of changes to the gauge which have the effect of leaving measurements unchanged. Symmetries of this kind are powerful tools for a deep understanding of the fundamental forces and particles of our physical world. Gauge invariance is therefore an important property within particle physics theory. They are closely connected to conservation laws and are described mathematically using group theory. Quantum field theory and the Standard Model are both gauge invariant theories – meaning they focus on properties of our universe, demonstrating this property of gauge invariance and the symmetries which are involved.

Gauge boson (rest) mass problem

Quantum field theories based on gauge invariance had been used with great success in understanding the electromagnetic and strong forces, but by around 1960, all attempts to create a gauge invariant theory for the weak force (and its combination with the electromagnetic force, known together as the electroweak interaction) had consistently failed. As a result of these failures, gauge theories began to fall into disrepute. The problem was symmetry requirements for these two forces incorrectly predicted the weak force's gauge bosons (W and Z) would have "zero mass" (in the specialized terminology of particle physics, "mass" refers specifically to a particle's rest mass). But experiments showed the W and Z gauge bosons had non-zero (rest) mass.[21]

Further, many promising solutions seemed to require the existence of extra particles known as Goldstone bosons. But evidence suggested these did not exist either. This meant either gauge invariance was an incorrect approach, or something unknown was giving the weak force's W and Z bosons their mass, and doing it in a way that did not create Goldstone bosons. By the late 1950s and early 1960s, physicists were at a loss as to how to resolve these issues, or how to create a comprehensive theory for particle physics.

Symmetry breaking

In the late 1950s, Yoichiro Nambu recognised that spontaneous symmetry breaking, a process where a symmetric system becomes asymmetric, could occur under certain conditions.[d] Symmetry breaking is when some variable that previously didn't affect the measured results (it was originally a "symmetry") now does affect the measured results (it's now "broken" and no longer a symmetry). In 1962 physicist Philip Anderson, an expert in condensed matter physics, observed that symmetry breaking played a role in superconductivity, and suggested it could also be part of the answer to the problem of gauge invariance in particle physics.

Specifically, Anderson suggested that the Goldstone bosons that would result from symmetry breaking might instead, in some circumstances, be "absorbed"[e] by the massless W and Z bosons. If so, perhaps the Goldstone bosons would not exist, and the W and Z bosons could gain mass, solving both problems at once. Similar behaviour was already theorised in superconductivity.[22] In 1964, this was shown to be theoretically possible by physicists Abraham Klein and Benjamin Lee, at least for some limited (non-relativistic) cases.[23]

Higgs mechanism

Following the 1963[24] and early 1964[23] papers, three groups of researchers independently developed these theories more completely, in what became known as the 1964 PRL symmetry breaking papers. All three groups reached similar conclusions and for all cases, not just some limited cases. They showed that the conditions for electroweak symmetry would be "broken" if an unusual type of field existed throughout the universe, and indeed, there would be no Goldstone bosons and some existing bosons would acquire mass.

The field required for this to happen (which was purely hypothetical at the time) became known as the Higgs field (after Peter Higgs, one of the researchers) and the mechanism by which it led to symmetry breaking, known as the Higgs mechanism. A key feature of the necessary field is that it would take less energy for the field to have a non-zero value than a zero value, unlike all other known fields, therefore, the Higgs field has a non-zero value (or vacuum expectation) everywhere. This non-zero value could in theory break electroweak symmetry. It was the first proposal capable of showing how the weak force gauge bosons could have mass despite their governing symmetry, within a gauge invariant theory.

Although these ideas did not gain much initial support or attention, by 1972 they had been developed into a comprehensive theory and proved capable of giving "sensible" results that accurately described particles known at the time, and which, with exceptional accuracy, predicted several other particles discovered during the following years.[f] During the 1970s these theories rapidly became the Standard Model of particle physics.

Higgs field

To allow symmetry breaking, the Standard Model includes a field of the kind needed to "break" electroweak symmetry and give particles their correct mass. This field, which became known as the "Higgs Field", was hypothesized to exist throughout space, and to break some symmetry laws of the electroweak interaction, triggering the Higgs mechanism. It, therefore, would cause the W and Z gauge bosons of the weak force to be massive at all temperatures below an extremely high value.[g] When the weak force bosons acquire mass, this affects the distance they can freely travel, which becomes very small, also matching experimental findings.[h] Furthermore, it was later realised that the same field would also explain, in a different way, why other fundamental constituents of matter (including electrons and quarks) have mass.

Unlike all other known fields, such as the electromagnetic field, the Higgs field is a scalar field, and has a non-zero average value in vacuum.

The "central problem"

There was not yet any direct evidence that the Higgs field existed, but even without direct proof, the accuracy of its predictions led scientists to believe the theory might be true. By the 1980s, the question of whether the Higgs field existed, and therefore whether the entire Standard Model was correct, had come to be regarded as one of the most important unanswered questions in particle physics.

For many decades, scientists had no way to determine whether the Higgs field existed because the technology needed for its detection did not exist at that time. If the Higgs field did exist, then it would be unlike any other known fundamental field, but it also was possible that these key ideas, or even the entire Standard Model, were somehow incorrect.[i]

The existence of the Higgs field became the last unverified part of the Standard Model of particle physics, and for several decades was considered "the central problem in particle physics".[26][27]

The hypothesised Higgs theory made several key predictions.[f][28]: 22 One crucial prediction was that a matching particle, called the "Higgs boson", should also exist. Proving the existence of the Higgs boson would prove whether the Higgs field existed, and therefore finally prove whether the Standard Model's explanation was correct. Therefore, there was an extensive search for the Higgs boson, as a way to prove the Higgs field itself existed.[11][12]

Search and discovery

Although the Higgs field would exist everywhere, proving its existence was far from easy. In principle, it can be proved to exist by detecting its excitations, which manifest as Higgs particles (the Higgs boson), but these are extremely difficult to produce and detect due to the energy required to produce them and their very rare production even if the energy is sufficient. It was, therefore, several decades before the first evidence of the Higgs boson could be found. Particle colliders, detectors, and computers capable of looking for Higgs bosons took more than 30 years (c. 1980~2010) to develop.

The importance of this fundamental question led to a 40-year search, and the construction of one of the world's most expensive and complex experimental facilities to date, CERN's Large Hadron Collider,[29] in an attempt to create Higgs bosons and other particles for observation and study. On 4 July 2012, the discovery of a new particle with a mass between 125 and 127 GeV/c2 was announced; physicists suspected that it was the Higgs boson.[30][j] [31][32]

Since then, the particle has been shown to behave, interact, and decay in many of the ways predicted for Higgs particles by the Standard Model, as well as having even parity and zero spin,[7][8] two fundamental attributes of a Higgs boson. This also means it is the first elementary scalar particle discovered in nature.[33]

By March 2013, the existence of the Higgs boson was confirmed, and therefore, the concept of some type of Higgs field throughout space is strongly supported.[30][32][7]

The presence of the field, now confirmed by experimental investigation, explains why some fundamental particles have (a rest) mass, despite the symmetries controlling their interactions, implying that they should be "massless." It also resolves several other long-standing puzzles, such as the reason for the extremely short distance travelled by the weak force bosons, and, therefore, the weak force's extremely short range.

As of 2018, in-depth research shows the particle continuing to behave in line with predictions for the Standard Model Higgs boson. More studies are needed to verify with higher precision that the discovered particle has all of the properties predicted or whether, as described by some theories, multiple Higgs bosons exist.[34]

The nature and properties of this field are now being investigated further, using more data collected at the LHC.[35]

Interpretation

Various analogies have been used to describe the Higgs field and boson, including analogies with well-known symmetry-breaking effects such as the rainbow and prism, electric fields, and ripples on the surface of water.

Other analogies based on the resistance of macro objects moving through media (such as people moving through crowds, or some objects moving through syrup or molasses) are commonly used but misleading, since the Higgs field does not actually resist particles, and the effect of mass is not caused by resistance.

Overview of Higgs boson and field properties

In the Standard Model, the Higgs boson is a massive scalar boson whose mass must be found experimentally. Its mass has been determined to be 125.35±0.15 GeV/c2 by CMS (2022)[36] and 125.11±0.11 GeV/c2 by ATLAS (2023). It is the only particle that remains massive even at very high energies. It has zero spin, even (positive) parity, no electric charge, and no colour charge, and it couples to (interacts with) mass.[13] It is also very unstable, decaying into other particles almost immediately via several possible pathways.

The Higgs field is a scalar field, with two neutral and two electrically charged components that form a complex doublet of the weak isospin SU(2) symmetry. Unlike any other known quantum field, it has a Sombrero potential. This shape means that below extremely high energies of about 159.5±1.5 GeV[37] such as those seen during the first picosecond (10−12 s) of the Big Bang, the Higgs field in its ground state takes less energy to have a nonzero vacuum expectation (value) than a zero value. Therefore in today's universe the Higgs field has a nonzero value everywhere (including otherwise empty space). This nonzero value in turn breaks the weak isospin SU(2) symmetry of the electroweak interaction everywhere. (Technically the non-zero expectation value converts the Lagrangian's Yukawa coupling terms into mass terms.) When this happens, three components of the Higgs field are "absorbed" by the SU(2) and U(1) gauge bosons (the "Higgs mechanism") to become the longitudinal components of the now-massive W and Z bosons of the weak force. The remaining electrically neutral component either manifests as a Higgs boson, or may couple separately to other particles known as fermions (via Yukawa couplings), causing these to acquire mass as well.[38]

Significance

Evidence of the Higgs field and its properties has been extremely significant for many reasons. The importance of the Higgs boson largely is that it is able to be examined using existing knowledge and experimental technology, as a way to confirm and study the entire Higgs field theory.[11][12] Conversely, proof that the Higgs field and boson did not exist would have also been significant.

Particle physics

Validation of the Standard Model

The Higgs boson validates the Standard Model through the mechanism of mass generation. As more precise measurements of its properties are made, more advanced extensions may be suggested or excluded. As experimental means to measure the field's behaviours and interactions are developed, this fundamental field may be better understood. If the Higgs field had not been discovered, the Standard Model would have needed to be modified or superseded.

Related to this, a belief generally exists among physicists that there is likely to be "new" physics beyond the Standard Model, and the Standard Model will at some point be extended or superseded. The Higgs discovery, as well as the many measured collisions occurring at the LHC, provide physicists a sensitive tool to search their data for any evidence that the Standard Model seems to fail, and could provide considerable evidence guiding researchers into future theoretical developments.

Symmetry breaking of the electroweak interaction

Below an extremely high temperature, electroweak symmetry breaking causes the electroweak interaction to manifest in part as the short-ranged weak force, which is carried by massive gauge bosons. In the history of the universe, electroweak symmetry breaking is believed to have happened at about 1 picosecond (10−12 s) after the Big Bang, when the universe was at a temperature 159.5±1.5 GeV/kB.[39] This symmetry breaking is required for atoms and other structures to form, as well as for nuclear reactions in stars, such as the Sun. The Higgs field is responsible for this symmetry breaking.

Particle mass acquisition

The Higgs field is pivotal in generating the masses of quarks and charged leptons (through Yukawa coupling) and the W and Z gauge bosons (through the Higgs mechanism).

It is worth noting that the Higgs field does not "create" mass out of nothing (which would violate the law of conservation of energy), nor is the Higgs field responsible for the mass of all particles. For example, approximately 99% of the mass of baryons (composite particles such as the proton and neutron), is due instead to quantum chromodynamic binding energy, which is the sum of the kinetic energies of quarks and the energies of the massless gluons mediating the strong interaction inside the baryons.[40] In Higgs-based theories, the property of "mass" is a manifestation of potential energy transferred to fundamental particles when they interact ("couple") with the Higgs field, which had contained that mass in the form of energy.[41]

Scalar fields and extension of the Standard Model

The Higgs field is the only scalar (spin-0) field to be detected; all the other fundamental fields in the Standard Model are spin- 1 /2 fermions or spin-1 bosons.[k] According to Rolf-Dieter Heuer, director general of CERN when the Higgs boson was discovered, this existence proof of a scalar field is almost as important as the Higgs's role in determining the mass of other particles. It suggests that other hypothetical scalar fields suggested by other theories, from the inflaton to quintessence, could perhaps exist as well.[42][43]

Cosmology

Inflaton

There has been considerable scientific research on possible links between the Higgs field and the inflaton – a hypothetical field suggested as the explanation for the expansion of space during the first fraction of a second of the universe (known as the "inflationary epoch"). Some theories suggest that a fundamental scalar field might be responsible for this phenomenon; the Higgs field is such a field, and its existence has led to papers analysing whether it could also be the inflaton responsible for this exponential expansion of the universe during the Big Bang. Such theories are highly tentative and face significant problems related to unitarity, but may be viable if combined with additional features such as large non-minimal coupling, a Brans–Dicke scalar, or other "new" physics, and they have received treatments suggesting that Higgs inflation models are still of interest theoretically.

Nature of the universe, and its possible fates

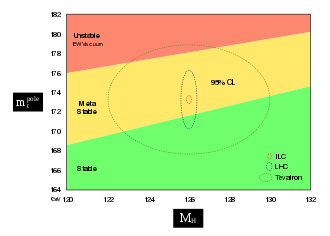

In the Standard Model, there exists the possibility that the underlying state of our universe – known as the "vacuum" – is long-lived, but not completely stable. In this scenario, the universe as we know it could effectively be destroyed by collapsing into a more stable vacuum state.[45][46][47][48][49] This was sometimes misreported as the Higgs boson "ending" the universe.[l] If the masses of the Higgs boson and top quark are known more precisely, and the Standard Model provides an accurate description of particle physics up to extreme energies of the Planck scale, then it is possible to calculate whether the vacuum is stable or merely long-lived.[52][53][54] A Higgs mass of 125–127 GeV/c2 seems to be extremely close to the boundary for stability, but a definitive answer requires much more precise measurements of the pole mass of the top quark.[44] New physics can change this picture.[55]

If measurements of the Higgs boson suggest that our universe lies within a false vacuum of this kind, then it would imply – more than likely in many billions of years[56][m] – that the universe's forces, particles, and structures could cease to exist as we know them (and be replaced by different ones), if a true vacuum happened to nucleate.[56][n] It also suggests that the Higgs self-coupling λ and its βλ function could be very close to zero at the Planck scale, with "intriguing" implications, including theories of gravity and Higgs-based inflation.[44]: 218 [58][59] A future electron–positron collider would be able to provide the precise measurements of the top quark needed for such calculations.[44]

Vacuum energy and the cosmological constant

More speculatively, the Higgs field has also been proposed as the energy of the vacuum, which at the extreme energies of the first moments of the Big Bang caused the universe to be a kind of featureless symmetry of undifferentiated, extremely high energy. In this kind of speculation, the single unified field of a Grand Unified Theory is identified as (or modelled upon) the Higgs field, and it is through successive symmetry breakings of the Higgs field, or some similar field, at phase transitions that the presently known forces and fields of the universe arise.[60]

The relationship (if any) between the Higgs field and the presently observed vacuum energy density of the universe has also come under scientific study. As observed, the present vacuum energy density is extremely close to zero, but the energy densities predicted from the Higgs field, supersymmetry, and other current theories are typically many orders of magnitude larger. It is unclear how these should be reconciled. This cosmological constant problem remains a major unanswered problem in physics.

History

Theorisation

The six authors of the 1964 PRL papers, who received the 2010 J. J. Sakurai Prize for their work; from left to right: Kibble, Guralnik, Hagen, Englert, Brout; right image: Higgs. |

Particle physicists study matter made from fundamental particles whose interactions are mediated by exchange particles – gauge bosons – acting as force carriers. At the beginning of the 1960s a number of these particles had been discovered or proposed, along with theories suggesting how they relate to each other, some of which had already been reformulated as field theories in which the objects of study are not particles and forces, but quantum fields and their symmetries.[61]: 150 However, attempts to produce quantum field models for two of the four known fundamental forces – the electromagnetic force and the weak nuclear force – and then to unify these interactions, were still unsuccessful.

One known problem was that gauge invariant approaches, including non-abelian models such as Yang–Mills theory (1954), which held great promise for unified theories, also seemed to predict known massive particles as massless.[22] Goldstone's theorem, relating to continuous symmetries within some theories, also appeared to rule out many obvious solutions,[62] since it appeared to show that zero-mass particles known as Goldstone bosons would also have to exist that simply were "not seen".[63] According to Guralnik, physicists had "no understanding" how these problems could be overcome.[63]

Particle physicist and mathematician Peter Woit summarised the state of research at the time:

Yang and Mills work on non-abelian gauge theory had one huge problem: in perturbation theory it has massless particles which don't correspond to anything we see. One way of getting rid of this problem is now fairly well understood, the phenomenon of confinement realized in QCD, where the strong interactions get rid of the massless "gluon" states at long distances. By the very early sixties, people had begun to understand another source of massless particles: spontaneous symmetry breaking of a continuous symmetry. What Philip Anderson realized and worked out in the summer of 1962 was that, when you have both gauge symmetry and spontaneous symmetry breaking, the massless Nambu–Goldstone mode which gives rise to Goldstone bosons can combine with the massless gauge field modes which give rise to massless gauge bosons to produce a physical massive vector field gauge bosons with mass. This is what happens in superconductivity, a subject about which Anderson was (and is) one of the leading experts.[22] text condensed

The Higgs mechanism is a process by which vector bosons can acquire rest mass without explicitly breaking gauge invariance, as a byproduct of spontaneous symmetry breaking.[64][65] Initially, the mathematical theory behind spontaneous symmetry breaking was conceived and published within particle physics by Yoichiro Nambu in 1960[66] (and somewhat anticipated by Ernst Stueckelberg in 1938[67]), and the concept that such a mechanism could offer a possible solution for the "mass problem" was originally suggested in 1962 by Philip Anderson, who had previously written papers on broken symmetry and its outcomes in superconductivity.[68] Anderson concluded in his 1963 paper on the Yang–Mills theory, that "considering the superconducting analog ... these two types of bosons seem capable of canceling each other out ... leaving finite mass bosons"),[69][24] and in March 1964, Abraham Klein and Benjamin Lee showed that Goldstone's theorem could be avoided this way in at least some non-relativistic cases, and speculated it might be possible in truly relativistic cases.[23]

These approaches were quickly developed into a full relativistic model, independently and almost simultaneously, by three groups of physicists: by François Englert and Robert Brout in August 1964;[70] by Peter Higgs in October 1964;[71] and by Gerald Guralnik, Carl Hagen, and Tom Kibble (GHK) in November 1964.[72] Higgs also wrote a short, but important,[64] response published in September 1964 to an objection by Gilbert,[73] which showed that if calculating within the radiation gauge, Goldstone's theorem and Gilbert's objection would become inapplicable.[o] Higgs later described Gilbert's objection as prompting his own paper.[74] Properties of the model were further considered by Guralnik in 1965,[75] by Higgs in 1966,[76] by Kibble in 1967,[77] and further by GHK in 1967.[78] The original three 1964 papers demonstrated that when a gauge theory is combined with an additional charged scalar field that spontaneously breaks the symmetry, the gauge bosons may consistently acquire a finite mass.[64][65][79] In 1967, Steven Weinberg[80] and Abdus Salam[81] independently showed how a Higgs mechanism could be used to break the electroweak symmetry of Sheldon Glashow's unified model for the weak and electromagnetic interactions,[82] (itself an extension of work by Schwinger), forming what became the Standard Model of particle physics. Weinberg was the first to observe that this would also provide mass terms for the fermions.[83][p]

At first, these seminal papers on spontaneous breaking of gauge symmetries were largely ignored, because it was widely believed that the (non-Abelian gauge) theories in question were a dead-end, and in particular that they could not be renormalised. In 1971–72, Martinus Veltman and Gerard 't Hooft proved renormalisation of Yang–Mills was possible in two papers covering massless, and then massive, fields.[83] Their contribution, and the work of others on the renormalisation group – including "substantial" theoretical work by Russian physicists Ludvig Faddeev, Andrei Slavnov, Efim Fradkin, and Igor Tyutin[84] – was eventually "enormously profound and influential",[85] but even with all key elements of the eventual theory published there was still almost no wider interest. For example, Coleman found in a study that "essentially no-one paid any attention" to Weinberg's paper prior to 1971[86] and discussed by David Politzer in his 2004 Nobel speech.[85] – now the most cited in particle physics[87] – and even in 1970 according to Politzer, Glashow's teaching of the weak interaction contained no mention of Weinberg's, Salam's, or Glashow's own work.[85] In practice, Politzer states, almost everyone learned of the theory due to physicist Benjamin Lee, who combined the work of Veltman and 't Hooft with insights by others, and popularised the completed theory.[85] In this way, from 1971, interest and acceptance "exploded"[85] and the ideas were quickly absorbed in the mainstream.[83][85]

The resulting electroweak theory and Standard Model have accurately predicted (among other things) weak neutral currents, three bosons, the top and charm quarks, and with great precision, the mass and other properties of some of these.[f] Many of those involved eventually won Nobel Prizes or other renowned awards. A 1974 paper and comprehensive review in Reviews of Modern Physics commented that "while no one doubted the mathematical correctness of these arguments, no one quite believed that nature was diabolically clever enough to take advantage of them",[88] adding that the theory had so far produced accurate answers that accorded with experiment, but it was unknown whether the theory was fundamentally correct.[89] By 1986 and again in the 1990s it became possible to write that understanding and proving the Higgs sector of the Standard Model was "the central problem today in particle physics".[26][27]

Summary and impact of the PRL papersedit

The three papers written in 1964 were each recognised as milestone papers during Physical Review Letters's 50th anniversary celebration.[79] Their six authors were also awarded the 2010 J. J. Sakurai Prize for Theoretical Particle Physics for this work.[90] (A controversy also arose the same year, because in the event of a Nobel Prize only up to three scientists could be recognised, with six being credited for the papers.[91]) Two of the three PRL papers (by Higgs and by GHK) contained equations for the hypothetical field that eventually would become known as the Higgs field and its hypothetical quantum, the Higgs boson.[71][72] Higgs' subsequent 1966 paper showed the decay mechanism of the boson; only a massive boson can decay and the decays can prove the mechanism.[citation needed]

In the paper by Higgs the boson is massive, and in a closing sentence Higgs writes that "an essential feature" of the theory "is the prediction of incomplete multiplets of scalar and vector bosons".[71] (Frank Close comments that 1960s gauge theorists were focused on the problem of massless vector bosons, and the implied existence of a massive scalar boson was not seen as important; only Higgs directly addressed it.[92]: 154, 166, 175 ) In the paper by GHK the boson is massless and decoupled from the massive states.[72] In reviews dated 2009 and 2011, Guralnik states that in the GHK model the boson is massless only in a lowest-order approximation, but it is not subject to any constraint and acquires mass at higher orders, and adds that the GHK paper was the only one to show that there are no massless Goldstone bosons in the model and to give a complete analysis of the general Higgs mechanism.[63][93] All three reached similar conclusions, despite their very different approaches: Higgs' paper essentially used classical techniques, Englert and Brout's involved calculating vacuum polarisation in perturbation theory around an assumed symmetry-breaking vacuum state, and GHK used operator formalism and conservation laws to explore in depth the ways in which Goldstone's theorem may be worked around.[64] Some versions of the theory predicted more than one kind of Higgs fields and bosons, and alternative "Higgsless" models were considered until the discovery of the Higgs boson.

Experimental searchedit

To produce Higgs bosons, two beams of particles are accelerated to very high energies and allowed to collide within a particle detector. Occasionally, although rarely, a Higgs boson will be created fleetingly as part of the collision byproducts. Because the Higgs boson decays very quickly, particle detectors cannot detect it directly. Instead the detectors register all the decay products (the decay signature) and from the data the decay process is reconstructed. If the observed decay products match a possible decay process (known as a decay channel) of a Higgs boson, this indicates that a Higgs boson may have been created. In practice, many processes may produce similar decay signatures. Fortunately, the Standard Model precisely predicts the likelihood of each of these, and each known process, occurring. So, if the detector detects more decay signatures consistently matching a Higgs boson than would otherwise be expected if Higgs bosons did not exist, then this would be strong evidence that the Higgs boson exists.

Because Higgs boson production in a particle collision is likely to be very rare (1 in 10 billion at the LHC),[q] and many other possible collision events can have similar decay signatures, the data of hundreds of trillions of collisions needs to be analysed and must "show the same picture" before a conclusion about the existence of the Higgs boson can be reached. To conclude that a new particle has been found, particle physicists require that the statistical analysis of two independent particle detectors each indicate that there is less than a one-in-a-million chance that the observed decay signatures are due to just background random Standard Model events – i.e., that the observed number of events is more than five standard deviations (sigma) different from that expected if there was no new particle. More collision data allows better confirmation of the physical properties of any new particle observed, and allows physicists to decide whether it is indeed a Higgs boson as described by the Standard Model or some other hypothetical new particle.

To find the Higgs boson, a powerful particle accelerator was needed, because Higgs bosons might not be seen in lower-energy experiments. The collider needed to have a high luminosity in order to ensure enough collisions were seen for conclusions to be drawn. Finally, advanced computing facilities were needed to process the vast amount of data (25 petabytes per year as of 2012) produced by the collisions.[96] For the announcement of 4 July 2012, a new collider known as the Large Hadron Collider was constructed at CERN with a planned eventual collision energy of 14 TeV – over seven times any previous collider – and over 300 trillion (3×10+14) LHC proton–proton collisions were analysed by the LHC Computing Grid, the world's largest computing grid (as of 2012), comprising over 170 computing facilities in a worldwide network across 36 countries.[96][97][98]

Search before 4 July 2012edit

The first extensive search for the Higgs boson was conducted at the Large Electron–Positron Collider (LEP) at CERN in the 1990s. At the end of its service in 2000, LEP had found no conclusive evidence for the Higgs.[r] This implied that if the Higgs boson were to exist it would have to be heavier than 114.4 GeV/c2.[99]

The search continued at Fermilab in the United States, where the Tevatron – the collider that discovered the top quark in 1995 – had been upgraded for this purpose. There was no guarantee that the Tevatron would be able to find the Higgs, but it was the only supercollider that was operational since the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) was still under construction and the planned Superconducting Super Collider had been cancelled in 1993 and never completed. The Tevatron was only able to exclude further ranges for the Higgs mass, and was shut down on 30 September 2011 because it no longer could keep up with the LHC. The final analysis of the data excluded the possibility of a Higgs boson with a mass between 147 GeV/c2 and 180 GeV/c2. In addition, there was a small (but not significant) excess of events possibly indicating a Higgs boson with a mass between 115 GeV/c2 and 140 GeV/c2.[100]

The Large Hadron Collider at CERN in Switzerland, was designed specifically to be able to either confirm or exclude the existence of the Higgs boson. Built in a 27 km tunnel under the ground near Geneva originally inhabited by LEP, it was designed to collide two beams of protons, initially at energies of 3.5 TeV per beam (7 TeV total), or almost 3.6 times that of the Tevatron, and upgradeable to 2 × 7 TeV (14 TeV total) in future. Theory suggested if the Higgs boson existed, collisions at these energy levels should be able to reveal it. As one of the most complicated scientific instruments ever built, its operational readiness was delayed for 14 months by a magnet quench event nine days after its inaugural tests, caused by a faulty electrical connection that damaged over 50 superconducting magnets and contaminated the vacuum system.[101][102][103]

Data collection at the LHC finally commenced in March 2010.[104] By December 2011 the two main particle detectors at the LHC, ATLAS and CMS, had narrowed down the mass range where the Higgs could exist to around 116–130 GeV/c2 (ATLAS) and 115–127 GeV/c2 (CMS).[105][106] There had also already been a number of promising event excesses that had "evaporated" and proven to be nothing but random fluctuations. However, from around May 2011,[107] both experiments had seen among their results, the slow emergence of a small yet consistent excess of gamma and 4-lepton decay signatures and several other particle decays, all hinting at a new particle at a mass around 125 GeV/c2.[107] By around November 2011, the anomalous data at 125 GeV/c2 was becoming "too large to ignore" (although still far from conclusive), and the team leaders at both ATLAS and CMS each privately suspected they might have found the Higgs.[107] On 28 November 2011, at an internal meeting of the two team leaders and the director general of CERN, the latest analyses were discussed outside their teams for the first time, suggesting both ATLAS and CMS might be converging on a possible shared result at 125 GeV/c2, and initial preparations commenced in case of a successful finding.[107] While this information was not known publicly at the time, the narrowing of the possible Higgs range to around 115–130 GeV/2 and the repeated observation of small but consistent event excesses across multiple channels at both ATLAS and CMS in the 124–126 GeV/c2 region (described as "tantalising hints" of around 2–3 sigma) were public knowledge with "a lot of interest".[108] It was therefore widely anticipated around the end of 2011, that the LHC would provide sufficient data to either exclude or confirm the finding of a Higgs boson by the end of 2012, when their 2012 collision data (with slightly higher 8 TeV collision energy) had been examined.[108][109]

Discovery of candidate boson at CERNedit

|

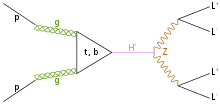

| Feynman diagrams showing the cleanest channels associated with the low-mass (~125 GeV/c2) Higgs boson candidate observed by ATLAS and CMS at the LHC. The dominant production mechanism at this mass involves two gluons from each proton fusing to a Top-quark Loop, which couples strongly to the Higgs field to produce a Higgs boson. Experimental analysis of these channels reached a significance of more than five standard deviations (sigma) in both experiments.[110][111][112]

|

On 22 June 2012 CERN announced an upcoming seminar covering tentative findings for 2012,[113][114] and shortly afterwards (from around 1 July 2012 according to an analysis of the spreading rumour in social media[115]) rumours began to spread in the media that this would include a major announcement, but it was unclear whether this would be a stronger signal or a formal discovery.[116][117] Speculation escalated to a "fevered" pitch when reports emerged that Peter Higgs, who proposed the particle, was to be attending the seminar,[118][119] and that "five leading physicists" had been invited – generally believed to signify the five living 1964 authors – with Higgs, Englert, Guralnik, Hagen attending and Kibble confirming his invitation (Brout having died in 2011).[120]

On 4 July 2012 both of the CERN experiments announced they had independently made the same discovery:[121] CMS of a previously unknown boson with mass 125.3±0.6 GeV/c2[122][123] and ATLAS of a boson with mass 126.0±0.6 GeV/c2.[124][125] Using the combined analysis of two interaction types (known as 'channels'), both experiments independently reached a local significance of 5 sigma – implying that the probability of getting at least as strong a result by chance alone is less than one in three million. When additional channels were taken into account, the CMS significance was reduced to 4.9 sigma.[123]

The two teams had been working 'blinded' from each other from around late 2011 or early 2012,[107] meaning they did not discuss their results with each other, providing additional certainty that any common finding was genuine validation of a particle.[96] This level of evidence, confirmed independently by two separate teams and experiments, meets the formal level of proof required to announce a confirmed discovery.

On 31 July 2012, the ATLAS collaboration presented additional data analysis on the "observation of a new particle", including data from a third channel, which improved the significance to 5.9 sigma (1 in 588 million chance of obtaining at least as strong evidence by random background effects alone) and mass 126.0 ± 0.4 (stat) ± 0.4 (sys) GeV/c2,[125] and CMS improved the significance to 5-sigma and mass 125.3 ± 0.4 (stat) ± 0.5 (sys) GeV/c2.[122]

New particle tested as a possible Higgs bosonedit

Following the 2012 discovery, it was still unconfirmed whether the 125 GeV/c2 particle was a Higgs boson. On one hand, observations remained consistent with the observed particle being the Standard Model Higgs boson, and the particle decayed into at least some of the predicted channels. Moreover, the production rates and branching ratios for the observed channels broadly matched the predictions by the Standard Model within the experimental uncertainties. However, the experimental uncertainties currently still left room for alternative explanations, meaning an announcement of the discovery of a Higgs boson would have been premature.[126] To allow more opportunity for data collection, the LHC's proposed 2012 shutdown and 2013–14 upgrade were postponed by seven weeks into 2013.[127]

In November 2012, in a conference in Kyoto researchers said evidence gathered since July was falling into line with the basic Standard Model more than its alternatives, with a range of results for several interactions matching that theory's predictions.[128] Physicist Matt Strassler highlighted "considerable" evidence that the new particle is not a pseudoscalar negative parity particle (consistent with this required finding for a Higgs boson), "evaporation" or lack of increased significance for previous hints of non-Standard Model findings, expected Standard Model interactions with W and Z bosons, absence of "significant new implications" for or against supersymmetry, and in general no significant deviations to date from the results expected of a Standard Model Higgs boson.[s] However some kinds of extensions to the Standard Model would also show very similar results;[130] so commentators noted that based on other particles that are still being understood long after their discovery, it may take years to be sure, and decades to fully understand the particle that has been found.[128][s]

These findings meant that as of January 2013, scientists were very sure they had found an unknown particle of mass ~125 GeV/c2, and had not been misled by experimental error or a chance result. They were also sure, from initial observations, that the new particle was some kind of boson. The behaviours and properties of the particle, so far as examined since July 2012, also seemed quite close to the behaviours expected of a Higgs boson. Even so, it could still have been a Higgs boson or some other unknown boson, since future tests could show behaviours that do not match a Higgs boson, so as of December 2012 CERN still only stated that the new particle was "consistent with" the Higgs boson,[30][32] and scientists did not yet positively say it was the Higgs boson.[131] Despite this, in late 2012, widespread media reports announced (incorrectly) that a Higgs boson had been confirmed during the year.[137]

In January 2013, CERN director-general Rolf-Dieter Heuer stated that based on data analysis to date, an answer could be possible 'towards' mid-2013,[138] and the deputy chair of physics at Brookhaven National Laboratory stated in February 2013 that a "definitive" answer might require "another few years" after the collider's 2015 restart.[139] In early March 2013, CERN Research Director Sergio Bertolucci stated that confirming spin-0 was the major remaining requirement to determine whether the particle is at least some kind of Higgs boson.[140]

Confirmation of existence and current statusedit

On 14 March 2013 CERN confirmed the following:

CMS and ATLAS have compared a number of options for the spin-parity of this particle, and these all prefer no spin and even parity two fundamental criteria of a Higgs boson consistent with the Standard Model. This, coupled with the measured interactions of the new particle with other particles, strongly indicates that it is a Higgs boson.[7]

This also makes the particle the first elementary scalar particle to be discovered in nature.[33]

The following are examples of tests used to confirm that the discovered particle is the Higgs boson:[s][13]

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Higgs_boson

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk