A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

In urban planning, the grid plan, grid street plan, or gridiron plan is a type of city plan in which streets run at right angles to each other, forming a grid.

Two inherent characteristics of the grid plan, frequent intersections and orthogonal geometry, facilitate movement. The geometry helps with orientation and wayfinding and its frequent intersections with the choice and directness of route to desired destinations.

In ancient Rome, the grid plan method of land measurement was called centuriation. The grid plan dates from antiquity and originated in multiple cultures; some of the earliest planned cities were built using grid plans in the Indian subcontinent.

History

Ancient grid plans

By 2600 BC, Mohenjo-daro and Harappa, major cities of the Indus Valley civilization, were built with blocks divided by a grid of straight streets, running north–south and east–west. Each block was subdivided by small lanes.[1] The cities and monasteries of Sirkap, Taxila and Thimi (in the Indus and Kathmandu Valleys), dating from the 1st millennium BC to the 11th century AD, also had grid-based designs.[2]

A workers' village (2570–2500 BC) at Giza, Egypt, housed a rotating labor force and was laid out in blocks of long galleries separated by streets in a formal grid. Many pyramid-cult cities used a common orientation: a north–south axis from the royal palace and an east–west axis from the temple, meeting at a central plaza where King and God merged and crossed.

Hammurabi king of the Babylonian Empire in the 18th century BC, ordered the rebuilding of Babylon: constructing and restoring temples, city walls, public buildings, and irrigation canals. The streets of Babylon were wide and straight, intersected approximately at right angles, and were paved with bricks and bitumen.

The tradition of grid plans is continuous in China from the 15th century BC onward in the traditional urban planning of various ancient Chinese states. Guidelines put into written form in the Kaogongji during the Spring and Autumn period (770-476 BC) stated: "a capital city should be square on plan. Three gates on each side of the perimeter lead into the nine main streets that crisscross the city and define its grid-pattern. And for its layout the city should have the Royal Court situated in the south, the Marketplace in the north, the Imperial Ancestral Temple in the east and the Altar to the Gods of Land and Grain in the west."

Teotihuacan, near modern-day Mexico City, is the largest ancient grid-plan site in the Americas. The city's grid covered 21 square kilometres (8 square miles).

Perhaps the most well-known grid system is that spread through the colonies of the Roman Empire. The archetypal Roman Grid was introduced to Italy first by the Greeks, with such information transferred by way of trade and conquest.[3]

Ancient Greece

Although the idea of the grid was present in Hellenic societal and city planning, it was not pervasive prior to the 5th century BC. However, it slowly gained primacy through the work of Hippodamus of Miletus (498 – 408 BC), who planned and replanned many Greek cities in accordance with this form.[4] The concept of a grid as the ideal method of town planning had become widely accepted by the time of Alexander the Great. His conquests were a step in the propagation of the grid plan throughout colonies, some as far-flung as Taxila in Pakistan,[4] that would later be mirrored by the expansion of the Roman Empire. The Greek grid had its streets aligned roughly in relation to the cardinal points[4] and generally looked to take advantage of visual cues based on the hilly landscape typical of Greece and Asia Minor.[5] The street grid consisted of plateiai and stenophoi (equivalent to Roman decumani and cardines). This was probably best exemplified in Priene, in present-day western Turkey, where the orthogonal city grid was based on the cardinal points, on sloping terrain that struck views out[clarification needed] towards a river and the city of Miletus.[6]

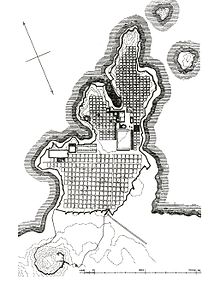

Ancient Rome

1.- Decumano; 2.- Cardo ; 3.- Foro de Caesaraugusta ; 4.- Puerto fluvial; 5.- Termas públicas; 6.- Teatro; 7.- Muralla

The Etruscan people, whose territories in Italy encompassed what would eventually become Rome, founded what is now the city of Marzabotto at the end of the 6th century BC. Its layout was based on Greek Ionic ideas, and it was here that the main east–west and north–south axes of a town (the decumanus maximus and cardo maximus respectively) could first be seen in Italy. According to Stanislawski (1946), the Romans did use grids until the time of the late Republic or early Empire, when they introduced centuriation, a system which they spread around the Mediterranean and into northern Europe later on.[3]

The military expansion of this period facilitated the adoption of the grid form as standard: the Romans established castra (forts or camps) first as military centres; some of them developed into administrative hubs. The Roman grid was similar in form to the Greek version of a grid but allowed for practical considerations. For example, Roman castra were often sited on flat land, especially close to or on important nodes like river crossings or intersections of trade routes.[5] The dimensions of the castra were often standard, with each of its four walls generally having a length of 660 metres (2,150 ft). Familiarity was the aim of such standardisation: soldiers could be stationed anywhere around the Empire, and orientation would be easy within established towns if they had a standard layout. Each would have the aforementioned decumanus maximus and cardo maximus at its heart, and their intersection would form the forum, around which would be sited important public buildings. Indeed, such was the degree of similarity between towns that Higgins states that soldiers "would be housed at the same address as they moved from castra to castra".[5] Pompeii has been cited by both Higgins[5] and Laurence[7][failed verification] as the best-preserved example of the Roman grid.

Outside of the castra, large tracts of land were also divided in accordance with the grid within the walls. These were typically 730 metres (2,400 ft) per side (called centuria) and contained 100 parcels of land (each called heredium).[8] The decumanus maximus and cardo maximus extended from the town gates out towards neighbouring settlements. These were lined up to be as straight as possible, only deviating from their path due to natural obstacles that prevented a direct route.[8]

While the imposition of only one town form regardless of region could be seen as an imposition of imperial authority, there is no doubting the practical reasoning behind the formation of the Roman grid. Under Roman guidance, the grid was designed for efficiency and interchangeability, both facilitated by and aiding the expansion of their empire.

Asia from the first millennium AD

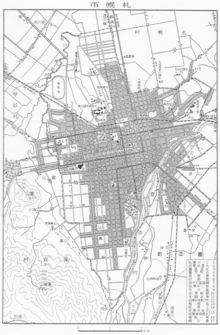

As Japan and the Korean peninsula became politically centralized in the 7th century AD, those societies adopted Chinese grid-planning principles in numerous locations. In Korea, Gyeongju, the capital of Unified Silla, and Sanggyeong, the capital of Balhae, adapted the Tang dynasty Chinese model. The ancient capitals of Japan, such as Fujiwara-Kyô (AD 694–710), Nara (Heijô-Kyô, AD 710–784), and Kyoto (Heian-Kyô, AD 794–1868) also adapted from Tang's capital, Chang'an. However, for reasons of defense, the planners of Tokyo eschewed the grid, opting instead for an irregular network of streets surrounding the Edo Castle grounds. In later periods, some parts of Tokyo were grid-planned, but grid plans are generally rare in Japan, and the Japanese addressing system is accordingly based on increasingly fine subdivisions, rather than a grid.

The grid-planning tradition in Asia continued through the beginning of the 20th century, with Sapporo, Japan (est. 1868) following a grid plan under American influence.

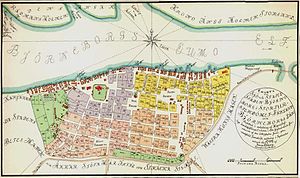

Europe and its colonies (12th-17th centuries)

New European towns were planned using grids beginning in the 12th century, most prodigiously in the bastides of southern France that were built during the 13th and 14th centuries. Medieval European new towns using grid plans were widespread, ranging from Wales to the Florentine region. Many were built on ancient grids originally established as Roman colonial outposts. In the British Isles, the planned new town system involving a grid street layout was part of the system of burgage. An example of a medieval planned city in The Netherlands is Elburg. Bury St Edmunds is an example of a town planned on a grid system in the late 11th century.[9]

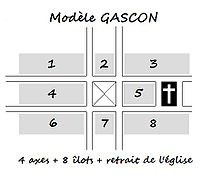

The Roman model was also used in Spanish settlements during the Reconquista of Ferdinand and Isabella. It was subsequently applied in the new cities established during the Spanish colonization of the Americas, after the founding of San Cristóbal de La Laguna (Canary Islands) in 1496. In 1573, King Philip II of Spain compiled the Laws of the Indies to guide the construction and administration of colonial communities. The Laws specified a square or rectangular central plaza with eight principal streets running from the plaza's corners. Hundreds of grid-plan communities throughout the Americas were established according to this pattern, echoing the practices of earlier Indian civilizations.

The baroque capital city of Malta, Valletta, dating back to the 16th century, was built following a rigid grid plan of uniformly designed houses, dotted with palaces, churches and squares.

The grid plan became popular with the start of the Renaissance in Northern Europe. In 1606, the newly founded city of Mannheim in Germany was the first Renaissance city laid out on the grid plan. Later came the New Town in Edinburgh and almost the entire city centre of Glasgow, and many planned communities and cities in Australia, Canada and the United States.

Derry, constructed in 1613–1618, was the first planned city in Ireland. The central diamond within a walled city with four gates was considered a good design for defence. The grid pattern was widely copied in the colonies of British North America.

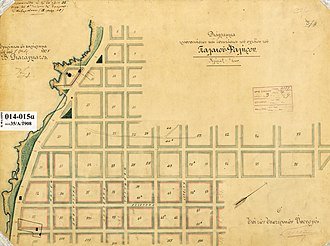

Russia (18th century)

In Russia the first planned city was St. Petersburg founded in 1703 by Peter I. Being aware of the modern European construction experience which he examined in the years of his Grand Embassy to Europe, the Czar ordered Domenico Trezzini to elaborate the first general plan of the city. The project of this architect for Vasilyevsky Island was a typical rectangular grid of streets (originally intended to be canals, like in Amsterdam), with three lengthwise thoroughfares, rectangularly crossed with about 30 crosswise streets.

The shape of street blocks on Vasilyevsky Island are the same, as was later implemented in the Commissioners' Plan of 1811 for Manhattan: elongated rectangles. The longest side of each block faces the relatively narrow street with a numeric name (in Petersburg they are called Liniya (Line)) while the shortest side faces wide avenues. To denote avenues in Petersburg, a special term prospekt was introduced. Inside the grid of Vasilyevsky Island there are three prospekts, named Bolshoi (Big), Sredniy (Middle) and Maly (Small) while the far ends of each line cross with the embankments of Bolshaya Neva and Smolenka rivers in the delta of the Neva River.

The peculiarity of 'lines' (streets) naming in this grid is that are each side of street has its own number, so one 'line' is a side of a street, not the whole street. The numbering is latently zero-based, however the supposed "zero line" has its proper name Kadetskaya liniya, while the opposite side of this street is called the '1-st Line'. Next street is named the '2-nd Line' on the eastern side, and the '3-rd Line' on the western side. After the reorganization of house numbering in 1834 and 1858 the even house numbers are used on the odd-numbered lines, and respectively odd house numbers are used for the even-numbered lines. The maximum numbers for 'lines' in Petersburg are 28-29th lines.

Later in the middle of the 18th century another grid of rectangular blocks with the numbered streets appeared in the continental part of the city: 13 streets named from the '1-st Rota' up to the '13-th Rota', where the companies (German: Rotte, Russian: рота) of the Izmaylovsky Regiment were located.

Early United States (17th-19th centuries)

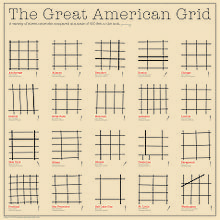

Many of the earliest cities in the United States, such as Boston, did not start with a grid system.[10] However, even in pre-revolutionary days some cities saw the benefits of such a layout. New Haven Colony, one of the earliest colonies in America, was designed with a tiny 9-square grid at its founding in 1638. On a grander scale, Philadelphia was designed on a rectilinear street grid in 1682, one of the first cities in North America to use a grid system.[11][12] At the urging of city founder William Penn, surveyor Thomas Holme designed a system of wide streets intersecting at right angles between the Schuylkill River to the west and the Delaware River to the east, including five squares of dedicated parkland. Penn advertised this orderly design as a safeguard against overcrowding, fire, and disease, which plagued European cities. Holme drafted an ideal version of the grid,[13] but alleyways sprouted within and between larger blocks as the city took shape. As the United States expanded westward, grid-based city planning modeled on Philadelphia's layout would become popular among frontier cities, making grids ubiquitous across the country.[14]

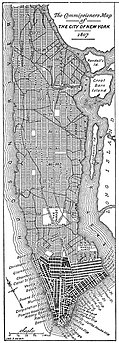

Another well-known grid plan is the plan for New York City formulated in the Commissioners' Plan of 1811, a proposal by the state legislature of New York for the development of most of Manhattan[15] above Houston Street.

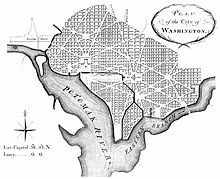

Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States, was planned under French-American architect Pierre Charles L'Enfant. Under the L'Enfant plan, the original District of Columbia was developed using a grid plan that is interrupted by diagonal avenues, most famously Pennsylvania Avenue. These diagonals are often connected by traffic circles, such as Dupont Circle and Washington Circle. As the city grew, the plan was duplicated to cover most of the remainder of the capital. Meanwhile, the core of the city faced disarray and the McMillan Plan, led by Senator James McMillan, was adopted to build a National Mall and a parks system that is still today a jewel of the city.

Often, some of the streets in a grid are numbered (First, Second, etc.), lettered, or arranged in alphabetical order. Downtown San Diego uses all three schemes: north–south streets are numbered from west to east, and east–west streets are split between a lettered series running southward from A through L and a series of streets named after trees or plants, running northward alphabetically from Ash to Walnut. As in many cities, some of these streets have been given new names violating the system (the former D Street is now Broadway, the former 12th Avenue is now Park Boulevard, etc.); this has meant that 2nd, not 1st, is the most common street name in the United States.[16]

An exception to the typical, uniform grid is the plan of Savannah, Georgia (1733), known as the Oglethorpe Plan. It is a composite, cellular city block consisting of four large corner blocks, four small blocks in between and a public square in the centre; the entire composition of approximately ten acres (four hectares) is known as a ward.[17] Its cellular structure includes all the primary land uses of a neighborhood and has for that reason been called fractal.[18] Its street configuration presages modern traffic calming techniques applied to uniform grids where certain selected streets become discontinuous or narrow, thus discouraging through traffic. The configuration also represents an example of functional shared space, where pedestrian and vehicular traffic can safely and comfortably coexist.[19]

In the westward development of the United States, the use of the grid plan was nearly universal in the construction of new settlements, such as in Salt Lake City (1870), Dodge City (1872) and Oklahoma City (1890). In these western cities the streets were numbered even more carefully than in the east to suggest future prosperity and metropolitan status.[11]

One of the main advantages of the grid plan was that it allowed the rapid subdivision and auction of a large parcel of land. For example, when the legislature of the Republic of Texas decided in 1839 to move the capital to a new site along the Colorado River, the functioning of the government required the rapid population of the town, which was named Austin. Charged with the task, Edwin Waller designed a fourteen-block grid that fronted the river on 640 acres (exactly 1 square mile; about 2.6 km2). After surveying the land, Waller organized the almost immediate sale of 306 lots, and by the end of the year the entire Texas government had arrived by oxcart at the new site. Apart from the speed of surveying advantage, the rationale at the time of the grid's adoption in this and other cities remains obscure.

Early 19th century – Australasia

In 1836 William Light drew up his plans for Adelaide, South Australia, spanning the River Torrens. Two areas south (the city centre) and north (North Adelaide) of the river were laid out in grid pattern, with the city surrounded by the Adelaide Park Lands.[20][21][22]

Hoddle Grid is the name given to the layout of Melbourne, Victoria, named after the surveyor Robert Hoddle, who marked it out in 1837 establishing the first formal town plan. This grid of streets, laid out when there were only a few hundred settlers, became the nucleus for what is now a city of over 5 million people, the city of Melbourne. The unusual dimensions of the allotments and the incorporation of narrow 'little' streets were the result of compromise between Hoddle's desire to employ the regulations established in 1829 by previous New South Wales Governor Ralph Darling, requiring square blocks and wide, spacious streets and Bourke's desire for rear access ways (now the 'little' streets, for example Little Collins Street).[23]

The city of Christchurch, New Zealand, was planned by Edward Jollie in 1850.[24]

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Gridiron_plan

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk