A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Part of a series on the |

| Bible |

|---|

|

|

Outline of Bible-related topics |

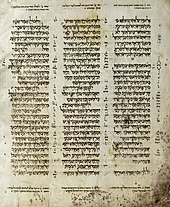

A biblical manuscript is any handwritten copy of a portion of the text of the Bible. Biblical manuscripts vary in size from tiny scrolls containing individual verses of the Jewish scriptures (see Tefillin) to huge polyglot codices (multi-lingual books) containing both the Hebrew Bible (Tanakh) and the New Testament, as well as extracanonical works.

The study of biblical manuscripts is important because handwritten copies of books can contain errors. Textual criticism attempts to reconstruct the original text of books, especially those published prior to the invention of the printing press.

Hebrew Bible (or Tanakh) manuscripts

The Aleppo Codex (c. 920 CE) and Leningrad Codex (c. 1008 CE) were once the oldest known manuscripts of the Tanakh in Hebrew. In 1947, the finding of the Dead Sea scrolls at Qumran pushed the manuscript history of the Tanakh back a millennium from such codices. Before this discovery, the earliest extant manuscripts of the Old Testament were in Greek, in manuscripts such as the Codex Vaticanus and Codex Sinaiticus. Out of the roughly 800 manuscripts found at Qumran, 220 are from the Tanakh. Every book of the Tanakh is represented except for the Book of Esther; however, most are fragmentary. Notably, there are two scrolls of the Book of Isaiah, one complete (1QIsa), and one around 75% complete (1QIsb). These manuscripts generally date between 150 BCE to 70 CE.[1]

Extant Tanakh manuscripts

| Version | Examples | Language | Date of Composition | Oldest Copy | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ketef Hinnom scrolls | Hebrew written in the Paleo-Hebrew alphabet | c. 650–587 BCE | c. 650–587 BCE[2] (amulets with the Priestly Blessing recorded in the Book of Numbers) | |||||||

| Dead Sea Scrolls | Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek | c. 150 BCE – 70 CE | c. 150 BCE – 70 CE (fragments) | |||||||

| Septuagint | Codex Vaticanus, Codex Sinaiticus and other earlier papyri | Greek | 300–100 BCE | 2nd century BCE (fragments) 4th century CE (complete) | ||||||

| Peshitta | Syriac | early 5th century CE | ||||||||

| Vulgate | Codex Amiatinus | Latin | early 5th century CE early 8th century CE (complete) | |||||||

| Masoretic | Aleppo Codex, Leningrad Codex and other, incomplete MSS[a] | Hebrew | c. 100 CE | 10th century CE (complete) | ||||||

| Samaritan Pentateuch | Hebrew | 200–100 BCE | Oldest extant MSS, c. 11th century CE; oldest MSS available to scholars, 16th century CE | |||||||

| Targum | Aramaic | 500–1000 C E | 5th century CE | |||||||

| Coptic | Crosby-Schøyen Codex, British Library MS. Oriental 7594 | Coptic | 3rd or 4th century CE | |||||||

New Testament manuscripts

The New Testament has been preserved in more manuscripts than any other ancient work of literature, with over 5,800 complete or fragmented Greek manuscripts catalogued, 10,000 Latin manuscripts and 9,300 manuscripts in various other ancient languages including Syriac, Slavic, Gothic, Ethiopic, Coptic, Nubian, and Armenian. The dates of these manuscripts range from c. 125 (the 𝔓52 papyrus, oldest copy of John fragment) to the introduction of printing in Germany in the 15th century.[citation needed]

Often, especially in monasteries, a manuscript cache was little more than a former manuscript recycling centre, where imperfect and incomplete copies of manuscripts were stored while the monastery or scriptorium decided what to do with them.[citation needed] There were several options. The first was to simply "wash" the manuscript and reuse it. Such reused manuscripts were called palimpsests and were very common in the ancient world until the Middle Ages. One notable palimpsest is the Archimedes Palimpsest. When washing was no longer an option, the second choice was burning. Since the manuscripts contained the words of Christ, they were thought to have had a level of sanctity;[citation needed] burning them was considered more reverent than simply throwing them into a garbage pit, which occasionally happened (as in the case of Oxyrhynchus 840). The third option was to leave them in what has become known as a manuscript gravesite. When scholars come across manuscript caches, such as at Saint Catherine's Monastery in the Sinai (the source of the Codex Sinaiticus), or Saint Sabbas Monastery outside Bethlehem, they are finding not libraries but storehouses of rejected texts[citation needed] sometimes kept in boxes or back shelves in libraries due to space constraints. The texts were unacceptable because of their scribal errors and contain corrections inside the lines,[3] possibly evidence that monastery scribes compared them to a master text. In addition, texts thought to be complete and correct but that had deteriorated from heavy usage or had missing folios would also be placed in the caches. Once in a cache, insects and humidity would often contribute to the continued deterioration of the documents.[citation needed]

Complete and correctly copied texts would usually be immediately placed in use and so wore out fairly quickly, which required frequent recopying. Manuscript copying was very costly when it required a scribe's attention for extended periods so a manuscript might be made only when it was commissioned. The size of the parchment, script used, any illustrations (thus raising the effective cost) and whether it was one book or a collection of several would be determined by the one commissioning the work. Stocking extra copies would likely have been considered wasteful and unnecessary since the form and the presentation of a manuscript were typically customized to the aesthetic tastes of the buyer.

| New Testament manuscripts | Lectionaries | ||||

| Century | Papyri | Uncials | Minuscules | Uncials | Minuscules |

| 2nd | 2 | - | - | - | - |

| 2nd/3rd | 5 | 1 | - | - | - |

| 3rd | 28 | 2 | - | - | - |

| 3rd/4th | 8 | 2 | - | - | - |

| 4th | 14 | 14 | - | 1 | - |

| 4th/5th | 8 | 8 | - | - | - |

| 5th | 2 | 36 | - | 1 | - |

| 5th/6th | 4 | 10 | - | - | - |

| 6th | 7 | 51 | - | 3 | - |

| 6th/7th | 5 | 5 | - | 1 | - |

| 7th | 8 | 28 | - | 4 | - |

| 7th/8th | 3 | 4 | - | - | - |

| 8th | 2 | 29 | - | 22 | - |

| 8th/9th | - | 4 | - | 5 | - |

| 9th | - | 53 | 13 | 113 | 5 |

| 9th/10th | - | 1 | 4 | - | 1 |

| 10th | - | 17 | 124 | 108 | 38 |

| 10th/11th | - | 3 | 8 | 3 | 4 |

| 11th | - | 1 | 429 | 15 | 227 |

| 11th/12th | - | - | 33 | - | 13 |

| 12th | - | - | 555 | 6 | 486 |

| 12th/13th | - | - | 26 | - | 17 |

| 13th | - | - | 547 | 4 | 394 |

| 13th/14th | - | - | 28 | - | 17 |

| 14th | - | - | 511 | - | 308 |

| 14th/15th | - | - | 8 | - | 2 |

| 15th | - | - | 241 | - | 171 |

| 15th/16th | - | - | 4 | - | 2 |

| 16th | - | - | 136 | - | 194 |

| Total | 94 | 269 | Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Gregory–Aland|||