A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Part of a series on the |

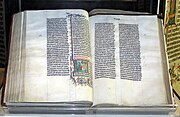

| Bible |

|---|

|

|

Outline of Bible-related topics |

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity and gender |

|---|

|

Women in the Bible are wives, mothers and daughters, servants, slaves and prostitutes. As both victors and victims, some women in the Bible change the course of important events while others are powerless to affect even their own destinies. The majority of women in the Bible are anonymous and unnamed. Individual portraits of various women in the Bible show women in a variety of roles. The New Testament refers to a number of women in Jesus' inner circle, and he is generally seen by scholars as dealing with women with respect and even equality.

Ancient Near Eastern societies have traditionally been described as patriarchal, and the Bible, as a document written by men, has traditionally been interpreted as patriarchal in its overall views of women.[1]: 9 [2]: 166–167 [3] Marital and inheritance laws in the Bible favor men, and women in the Bible exist under much stricter laws of sexual behavior than men. A woman in ancient biblical times was always subject to strict purity laws, both ritual and moral.

Recent scholarship accepts the presence of patriarchy in the Bible, but shows that heterarchy is also present: heterarchy acknowledges that different power structures between people can exist at the same time, that each power structure has its own hierarchical arrangements, and that women had some spheres of power of their own separate from men.[1]: 27 There is evidence of gender balance in the Bible, and there is no attempt in the Bible to portray women as deserving of less because of their "naturally evil" natures.

While women are not generally in the forefront of public life in the Bible, those women who are named are usually prominent for reasons outside the ordinary. For example, they are often involved in the overturning of human power structures in a common biblical literary device called "reversal". Abigail, David's wife, Esther the Queen, and Jael who drove a tent peg into the enemy commander's temple while he slept, are a few examples of women who turned the tables on men with power. The founding matriarchs are mentioned by name, as are some prophetesses, judges, heroines, and queens, while the common woman is largely, though not completely, unseen. The slave Hagar's story is told, and the prostitute Rahab's story is also told, among a few others.

The New Testament names women in positions of leadership in the early church as well. Views of women in the Bible have changed throughout history and those changes are reflected in art and culture. There are controversies within the contemporary Christian church concerning women and their role in the church.

Women, sex, and law in surrounding cultures

Almost all Near Eastern societies of the Bronze Age (3000–1200 BCE) and Axial Age (800 to 300 BCE) were established as patriarchal societies by 3000 BCE.[4]: xxxii Eastern societies such as the Akkadians, Hittites, Assyrians and Persians relegated women to an inferior and subordinate position. There are very few exceptions, but one can be found in the third millennium B.C. with the Sumerians who accorded women a position which was almost equal to that of men. However, by the second millennium, the rights and status of women were reduced.[5]: 42 [6]: 4–5

In the West, the status of Egyptian women was high, and their legal rights approached equality with men throughout the last three millennia BCE.[7]: 5–6 A few women even ruled as pharaohs.[7]: 7 However, historian Sarah Pomeroy explains that even in those ancient patriarchal societies where a woman could occasionally become queen, her position did not empower her female subjects.[8]: x

Classics scholar Bonnie MacLachlan writes that Greece and Rome were patriarchal cultures.[9]: vi

The roles women were expected to fill in all these ancient societies were predominantly domestic with a few exceptions such as Sparta, who fed women equally with men, and trained them to fight in the belief women would thereby produce stronger children. The predominant views of Ancient and Classical Greece were patriarchal; however, there is also a misogynistic strain present in Greek literature from its beginnings.[10]: 15 A polarized view of women allowed some classics authors, such as Thales, Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, Aristophanes and Philo, and others, to write about women as "twice as bad as men", a "pernicious race", "never to be trusted on any account", and as an inherently inferior race of beings separate from the race of men.[11]: 41, 42 [10]: 15–20 [8]: 18

Rome was heavily influenced by Greek thought.[12]: 248 Sarah Pomeroy says "never did Roman society encourage women to engage in the same activities as men of the same social class."[8]: xv In The World of Odysseus, classical scholar Moses Finley says: "There is no mistaking the fact that Homer fully reveals what remained true for the whole of antiquity: that women were held to be naturally inferior..."[10]: 16

Pomeroy also states that women played a vital role in classical Greek and Roman religion, sometimes attaining a freedom in religious activities denied to them elsewhere.[13] Wayne Meeks writes that there is no evidence this went beyond the internal practices of the religion itself. The mysteries created no alternative in larger society to the established patterns, but there is some evidence of a disruption of traditional women's roles within some of the mystery cults.[14]: 6 Priestesses in charge of official cults such as that of Athena Polias in ancient Athens were paid well, were looked upon as role models, and wielded considerable social and political power.[15] In the important Eleusinian Mysteries in ancient Greece, men, women, children and slaves were admitted and initiated into its secrets on a basis of complete equality.[16] In Rome, priestesses of state cults, such as the Vestal Virgins, were able to achieve positions of status and power. They were able to live independently from men, made ceremonial appearances at public events and could accrue considerable wealth.[17] Both ancient Greece and Rome celebrated important women-only religious festivals during which women were able to socialize and build bonds with each other.[18][19] Although the "ideal woman" in the writings and sayings of male philosophers and leaders was one who would stay out of the public view and attend to the running of her household and the upbringing of her children, in practice some women in both ancient Greece and Rome were able to attain considerable influence outside the purely domestic sphere.[20]

Laws in patriarchal societies regulated three sorts of sexual infractions involving women: rape, fornication (which includes adultery and prostitution), and incest.[21] There is a homogeneity to these codes across time, and across borders, which implies the aspects of life that these laws enforced were established practices within the norms and values of the populations.[4]: 48 The prominent use of corporal punishment, capital punishment, corporal mutilation, 'eye-for-an-eye' talion punishments, and vicarious punishments (children for their fathers) were standard across Mesopotamian Law.[5]: 72 Ur-Nammu, who founded the Sumerian Third Dynasty of Ur in southern Mesopotamia, sponsored the oldest surviving codes of law dating from approximately 2200 BCE.[5]: 10, 40 Most other codes of law date from the second millennium BCE including the famous Babylonian Laws of Hammurabi which dates to about 1750 BCE.[5]: 53 Ancient laws favored men, protecting the procreative rights of men as a common value in all the laws pertaining to women and sex.[21]: 14

In all these codes, rape is punished differently depending upon whether it occurs in the city where a woman's calls for help could be heard or the country where they could not be (as in Deuteronomy 22:23–27).[5]: 12 The Hittite laws also condemn a woman raped in her house presuming the man could not have entered without her permission.[22]: 198, 199 Fornication is a broad term for a variety of inappropriate sexual behaviors including adultery and prostitution. In the code of Hammurabi, and in the Assyrian code, both the adulterous woman and her lover are to be bound and drowned, but forgiveness could supply a reprieve.[23] In the Biblical law, (Leviticus 20:10; Deuteronomy 22:22) forgiveness is not an option: the lovers must die (Deuteronomy 22:21,24). No mention is made of an adulterous man in any code. In Hammurabi, a woman can apply for a divorce but must prove her moral worthiness or be drowned for asking. It is enough in all codes for two unmarried individuals engaged in a sexual relationship to marry. However, if a husband later accuses his wife of not having been a virgin when they married, she will be stoned to death.[24]: 94, 104

Until the codes introduced in the Hebrew Bible, most codes of law allowed prostitution. Classics scholars Allison Glazebrook and Madeleine M. Henry say attitudes concerning prostitution "cut to the core of societal attitude towards gender and to social constructions of sexuality."[25]: 3 Many women in a variety of ancient cultures were forced into prostitution.[21]: 413 Many were children and adolescents. According to the 5th century BCE historian Herodotus, the sacred prostitution of the Babylonians was "a shameful custom" requiring every woman in the country to go to the precinct of Venus, and consort with a stranger.[26]: 211 Some waited years for release while being used without say or pay. The initiation rituals of devdasi of pre-pubescent girls included a deflowering ceremony which gave Priests the right to have intercourse with every girl in the temple. In Greece, slaves were required to work as prostitutes and had no right to decline.[25]: 3 The Hebrew Bible code is the only one of these codes that condemns prostitution.[21]: 399–418

In the code of Hammurabi, as in Leviticus, incest is condemned and punishable by death, however, punishment is dependent upon whether the honor of another man has been compromised.[5]: 61 Genesis glosses over incest repeatedly, and in 2 Samuel and the time of King David, Tamar is still able to offer marriage to her half brother as an alternative to rape. Exodus, Leviticus, and Numbers condemn all sexual relations between relatives.[21]: 268–274

Hebrew Bible (Old Testament)

According to traditional Jewish enumeration, the Hebrew canon is composed of 24 books written by various authors, using primarily Hebrew and some Aramaic, which came into being over a span of almost a millennium.[27]: 17 [28]: 41 The Hebrew Bible's earliest texts reflect a Late Bronze Age Near Eastern civilization, while its last text, thought by most scholars to be the Book of Daniel, comes from a second century BCE Hellenistic world.[27]: 17

Compared to the number of men, few women are mentioned in the Bible by name. The exact number of named and unnamed women in the Bible is somewhat uncertain because of a number of difficulties involved in calculating the total. For example, the Bible sometimes uses different names for the same woman, names in different languages can be translated differently, and some names can be used for either men or women. Professor Karla Bombach says one study produced a total of 3000–3100 names, 2900 of which are men with 170 of the total being women. However, the possibility of duplication produced the recalculation of a total of 1700 distinct personal names in the Bible with 137 of them being women. In yet another study of the Hebrew Bible only, there were a total of 1426 names with 1315 belonging to men and 111 to women. Seventy percent of the named and unnamed women in the Bible come from the Hebrew Bible.[29]: 33, 34 "Despite the disparities among these different calculations, ... women or women's names represent between 5.5 and 8 percent of the total , a stunning reflection of the androcentric character of the Bible."[29]: 34 A study of women whose spoken words are recorded found 93, of which 49 women are named.[30]

The common, ordinary, everyday Hebrew woman is "largely unseen" in the pages of the Bible, and the women that are seen, are the unusual who rose to prominence.[31]: 5 These prominent women include the Matriarchs Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel, and Leah, Miriam the prophetess, Deborah the Judge, Huldah the prophetess, Abigail (who married David), Rahab, and Esther. A common phenomenon in the Bible is the pivotal role that women take in subverting man-made power structures. The result is often a more just outcome than what would have taken place under ordinary circumstances.[32]: 68 Law professor Geoffrey Miller explains that these women did not receive opposition for the roles they played, but were honored instead.[33]: 127

Views on gender

There has been substantial agreement for over one hundred years, among a wide variety of scholars, that the Hebrew Bible is a predominantly patriarchal document from a patriarchal age. New Testament scholar Ben Witherington III says it "limited women's roles and functions to the home, and severely restricted: (1) their rights of inheritance, (2) their choice of relationship, (3) their ability to pursue a religious education or fully participate in a synagogue, and (4) limited their freedom of movement."[34] Recent scholarship is calling some aspects of this into question.

the validity and appropriateness of to designate both families and society have recently been challenged in several disciplines: in classical scholarship, by using sources other than legal texts; in research on the Hebrew Bible and ancient Israel, also by using multiple sources; and in the work of third-wave feminists, both social theorists and feminist archaeologists. Taken together, these challenges provide compelling reasons for abandoning the patriarchy model as an adequate or accurate descriptor of ancient Israel.[1]: 9

Meyers argues for heterarchy over patriarchy as the appropriate term to describe ancient Israelite attitudes toward gender. Heterarchy acknowledges that different "power structures can exist simultaneously in any given society, with each structure having its own hierarchical arrangements that may cross-cut each other laterally".[1]: 27 Meyers says male dominance was real but fragmentary, with women also having spheres of influence of their own.[1]: 27 Women were responsible for "maintenance activities" including economic, social, political and religious life in both the household and the community.[1]: 20 The Old Testament lists twenty different professional-type positions that women held in ancient Israel.[1]: 22, 23 Meyers references Tikva Frymer-Kensky as saying that Deuteronomic laws were fair to women except in matters of sexuality.[3]

Frymer-Kensky says there is evidence of "gender blindness" in the Hebrew Bible.[2]: 166–167 Unlike other ancient literature, the Hebrew Bible does not explain or justify cultural subordination by portraying women as deserving of less because of their "naturally evil" natures. The Biblical depiction of early Bronze Age culture up through the Axial Age, depicts the "essence" of women, (that is the Bible's metaphysical view of being and nature), of both male and female as "created in the image of God" with neither one inherently inferior in nature.[11]: 41, 42 Discussions of the nature of women are conspicuously absent from the Hebrew Bible.[35] Biblical narratives do not show women as having different goals, desires, or strategies or as using methods that vary from those used by men not in authority.[35]: xv Judaic studies scholar David R. Blumenthal explains these strategies made use of "informal power" which was different from that of men with authority.[11]: 41, 42 There are no personality traits described as being unique to women in the Hebrew Bible.[35]: 166–167 Most theologians agree the Hebrew Bible does not depict the slave, the poor, or women, as different metaphysically in the manner other societies of the same eras did.[35]: 166–167 [11]: 41, 42 [10]: 15–20 [8]: 18

Theologians Evelyn Stagg and Frank Stagg say the Ten Commandments of Exodus 20 contain aspects of both male priority and gender balance.[36]: 21 In the tenth commandment against coveting, a wife is depicted in the examples of things, possessions, belonging to a man that are not to be coveted: house, wife, male or female slave, ox or donkey, or 'anything that belongs to your neighbour.' On the other hand, the fifth commandment to honor parents does not make any distinction in the honor to be shown between one parent and another.[37]: 11, 12

The Hebrew Bible often portrays women as victors, leaders, and heroines with qualities Israel should emulate. Women such as Hagar, Tamar, Miriam, Rahab, Deborah, Esther, and Yael/Jael, are among many female "saviors" of Israel. Tykva Frymer-Kensky says "victor stories follow the paradigm of Israel's central sacred story: the lowly are raised, the marginal come to the center, the poor boy makes good."[38]: 333–337 She goes on to say these women conquered the enemy "by their wits and daring, were symbolic representations of their people, and pointed to the salvation of Israel."[2]: 333–337

The Hebrew Bible portrays women as victims as well as victors.[2]: 166–167 For example, in Numbers 31, the Israelites slay the people of Midian, except for 32,000 virgin women who are kept as spoils of war.[39][40] Phyllis Trible, in her now famous work Texts of Terror, tells four Bible stories of suffering in ancient Israel where women are the victims. Tribble describes the Bible as "a mirror" that reflects humans, and human life, in all its "holiness and horror".[41] Frymer-Kensky says the Bible's authors use vulnerable women symbolically as "images of the Israel that is small and vulnerable..."[38]: 333–337 For Frymer-Kensky, "this is not misogynist story-telling but something far more complex in which the treatment of women becomes the clue to the morality of the social order."[2]: 174 Professor of Religion J. David Pleins says these tales are included by the Deuteronomic historian to demonstrate the evils of life without a centralized shrine and single political authority.[42]

Women did have some role in the ritual life of religion as represented in the Bible though they could not be priests; but then neither could just any man. Only male Levites could be priests. Women (as well as men) were required to make a pilgrimage to the Temple in Jerusalem once a year (men each of the three main festivals if they could) and offer the Passover sacrifice.[28]: 41 They would also do so on special occasions in their lives such as giving a todah ("thanksgiving") offering after childbirth. Hence, they participated in many of the major public religious roles that non-Levitical men could, albeit less often and on a somewhat smaller and generally more discreet scale.[43]: 167–169 Old Testament scholar Christine Roy Yoder says that in the Book of Proverbs, the divine attribute of Holy Wisdom is presented as female. She points out that "on the one hand" such a reference elevates women, and "on the other hand" the "strange" woman also in Proverbs "perpetuates the stereotype of woman as either wholly good or wholly evil."[44]

Economics

In traditional agrarian societies, a woman's role in the economic well-being of the household was an essential one. Ancient Israel had no developed market economy for most of the Iron Age, so a woman's role in commodity production was essential for survival.[1]: 22 Meyer's says that "women were largely responsible for food processing, textile production, and the fashioning of various household implements and containers (grinding tools, stone, and ceramic vessels, baskets, weaving implements, and sewing tools). Many of these tasks were not only time-consuming and physically demanding but also technologically sophisticated. ... As anthropologist Jack Goody noted, because women could transform the raw into the cooked and produce other essential commodities, they were seen as having the ability to "work ... wonders."[1]: 22

This translated into a share of power in the household. According to Meyer, women had a say in activities related to production and consumption, the allocation of household spaces and implements, supervision and assignment of tasks, and the use of resources in their own households and sometimes across households.[1]: 22 Meyers adds that "in traditional societies comparable to ancient Israel, when women and men both make significant economic contributions to household life, female–male relationships are marked by interdependence or mutual dependence. Thus, for many—but not all—household processes in ancient Israel, the marital union would have been a partnership. The different gendered components of household life cannot be lumped together; men dominated some aspects, women others.[1]: 20–22

A number of biblical texts, even with their androcentric perspective, support this conclusion. Women's managerial agency can be identified in some legal stipulations of the Covenant Code, in several narratives, and in Proverbs".[1]: 22 This assessment relies on "ethnographic evidence from traditional societies, not on how those tasks are viewed today in industrialized societies".[1]: 20

Sex, marriage and family

Talmudic scholar Judith Hauptman says marriage and family law in the Bible favored men over women. For example, a husband could divorce a wife if he chose to, but a wife could not divorce a husband without his consent. The law said a woman could not make a binding vow without the consent of her male authority, so she could not legally marry without male approval. The practice of levirate marriage applied to widows of childless deceased husbands, not to widowers of childless deceased wives. If either he or she did not consent to the marriage, a different ceremony called chalitza was done instead; this involves the widow removing her brother-in-law's shoe, spitting in front of him, and proclaiming, "This is what happens to someone who will not build his brother's house!".[43]: 163

Laws concerning the loss of female virginity have no male equivalent. Women in biblical times depended on men economically. Women had the right to own property jointly with their husbands, except in the rare case of inheriting land from a father who did not bear sons. Even "in such cases, women would be required to remarry within the tribe so as not to reduce its land holdings."[43]: 171 Property was transferred through the male line and women could not inherit unless there were no male heirs (Numbers 27:1–11; 36:1–12).[45]: 3 These and other gender-based differences found in the Torah suggest that women were seen as subordinate to men; however, they also suggest that biblical society viewed continuity, property, and family unity as more important than any individual.[43]

Philosopher Michael Berger says, the rural family was the backbone of biblical society. Women did tasks as important as those of men, managed their households, and were equals in daily life, but all public decisions were made by men. Men had specific obligations they were required to perform for their wives including the provision of clothing, food, and sexual relations.[46] Ancient Israel was a frontier and life was "tough". Everyone was a "small holder" and had to work hard to survive. A large percentage of children died early, and those that survived, learned to share the burdens and responsibilities of family life as they grew. The marginal environment required a strict authority structure: parents had to not just be honored but not be challenged. Ungovernable children, especially adult children, had to be kept in line or eliminated. Respect for the dead was obligatory, and sexual lines were rigidly drawn. Virginity was expected, adultery the worst of crimes, and even suspicion of adultery led to trial by ordeal.[47]: 1, 2

Adultery was defined differently for men than for women: a woman was an adulteress if she had sexual relations outside her marriage, but if a man had sexual relations outside his marriage with an unmarried woman, a concubine or a prostitute, it was not considered adultery on his part.[45]: 3 A woman was considered "owned by a master".[11]: 20, 21 A woman was always under the authority of a man: her father, her brothers, her husband, and since she did not inherit, eventually her eldest son.[47]: 1, 2 She was subject to strict purity laws, both ritual and moral, and non-conforming sex—homosexuality, bestiality, cross-dressing and masturbation—was punished. Stringent protection of the marital bond and loyalty to kin was very strong.[47]: 20

The zonah of the Hebrew Bible is a woman who is not under the authority of a man; she may be a paid prostitute, but not necessarily. In the Bible, for a woman or girl who was under the protection of a man to be called a "zonah" was a grave insult to her and her family. The zonah is shown as lacking protection, making each zonah vulnerable and available to other men; the lack of a specific man governing her meant that she was free to act in ways that other women were not. According to David Blumenthal, the Bible depicts the zonah as "dangerous, fearsome and threatening by her freedom, and yet appealing and attractive at the same time."[11]: 42 Her freedom is recognized by biblical law and her sexual activity is not punishable.[11]: 42 She is the source of extra-institutional sex. Therefore, she is seen as a threat to patriarchy and the family structure it supports.[11]: 43 Over time, the term "zonah" came to be applied to a married woman who committed adultery, and that sense of the term was used as a metaphor for the Jewish people being unfaithful to Yahweh, especially in the Book of Hosea and the Book of Ezekiel, where the descriptions of sexual acts and punishments are both brutal and pornographic.[11]: 43

Hagar and Sarah

Abraham is an important figure in the Bible, yet "his story pivots on two women."[48][49]: 9 Sarah was Abraham's wife and Hagar was Sarah's personal slave who became Abraham's concubine. Sarah is introduced in the Bible with only her name and that she is "barren" and without child. She had borne no children though God had promised them a child. Sarah is the first of barren women introduced, and the theme of infertility remains present throughout the matriarch narratives (Genesis 11:30, 25:21; 30:1–2).[50]

Later in the story Sarah overhears God's promise that she is to bear a child, and she does not believe it. "Abraham and Sarah were already very old, and Sarah was past the age of childbearing. Sarah laughed to herself as she thought, "After I am worn out and my lord is old, will I now have this pleasure?" (Genesis 18:10–15). Sarah's response to God's promise could imply different interpretations including the lack of Abraham's sexual response to Sarah, Sarah's emotional numbness due to infertility has put her in disbelief, or more traditionally, Sarah is relieved, and God has brought "joy out of sorrow through the birth of Issac".[50] Later on, Sarah relies on her beauty and gives her slave Hagar to Abraham as a concubine. Abraham then has sexual relations with her and Hagar becomes pregnant.[51]

Sarah hopes to build a family through Hagar, but Hagar "began to despise her mistress" (Genesis 16:4). Then Sarah mistreated Hagar, who fled. God spoke to the slave Hagar in the desert, sent her home, and she bore Abraham a son, Ishmael, "a wild donkey of a man" (Genesis 16:12). The text suggests that Sarah had made a mistake which could have been avoided if there had been a strong maternal-type presence to guide her.[51]

When Ishmael was 13, Abraham received the covenant practice of circumcision, and circumcised every male of his household. Sarah became pregnant and bore a son that they named Isaac when Abraham was a hundred years old. When Isaac was eight days old, Abraham circumcised him as well. Hagar and Ishmael are sent away again, and this time they do not return (Genesis 21:1–5). Frymer-Kensky says "This story starkly illuminates the relations between women in a patriarchy." She adds that it demonstrates the problems associated with gender intersecting with the disadvantages of class: Sarah has the power, her actions are legal, not compassionate, but her motives are clear: "she is vulnerable, making her incapable of compassion toward her social inferior."[52]: 98

Lot's daughters

Genesis 19 narrates that Lot and his two daughters live in Sodom, and are visited by two angels. A mob gathers, and Lot offers them his daughters to protect the angels, but the angels intervene. Sodom is destroyed, and the family goes to live in a cave. Since there are no men around except Lot, the daughters decide to make him drink wine and have him unknowingly impregnate them. They each have a son, Moab and Ben-Ammi.[53]

Additional women in Genesis and Exodus

Potiphar's Wife, whose false accusations of Joseph leads to his imprisonment. Pharaoh's Daughter, who rescues and cares for the infant Moses. Shiphrah and Puah, two Hebrew midwives who disobey Pharaoh's command to kill all newborn Hebrew boys. God favors them for this. Moses' wife Zipporah, who saves his life when God intends to kill him. Miriam, Moses' sister, a prophetess. Cozbi, a woman slain by Phinehas shortly before the Midian war.

Rahab

The book of Joshua tells the story of Rahab the prostitute (zonah), a resident of Jericho, who houses two spies sent by Joshua to prepare for an attack on the city. The king of Jericho knew the spies were there and sent soldiers to her house to capture them, but she hid them, sent the soldiers off in misdirection, and lied to the King on their behalf. She said to the spies, "I know that the Lord has given you this land and that a great fear of you has fallen on us, so that all who live in this country are melting in fear because of you. We have heard how the Lord dried up the water of the Red Sea for you when you came out of Egypt, and what you did to Sihon and Og, the two kings of the Amorites east of the Jordan, whom you completely destroyed. When we heard of it, our hearts melted in fear and everyone's courage failed because of you, for the Lord your God is God in heaven above and on the earth below. Now then, please swear to me by the Lord that you will show kindness to my family, because I have shown kindness to you. Give me a sure sign that you will spare the lives of my father and mother, my brothers and sisters, and all who belong to them—and that you will save us from death." (Joshua 2:9–13) She was told to tie a scarlet cord in the same window through which she helped the spies escape, and to have all her family in the house with her and not to go into the streets, and if she did not comply, their blood would be on their own heads. She did comply, and she and her whole family were saved before the city was captured and burned (Joshua 6).

Delilah

Judges chapters 13 to 16 tell the story of Samson who meets Delilah and his end in chapter 16. Samson was a Nazarite, a specially dedicated individual, from birth, yet his story indicates he violated every requirement of the Nazarite vow.[54] Long hair was only one of the symbolic representations of his special relationship with God, and it was the last one that Samson violated. Nathan MacDonald explains that touching the carcass of the lion and Samson's celebration of his wedding to a Philistine can be seen as the initial steps that led to his end.[55] Samson travels to Gaza and "fell in love with a woman in the Valley of Sorek whose name was Delilah. The rulers of the Philistines went to her and said, "See if you can lure him into showing you the secret of his great strength and how we can overpower him so we may tie him up and subdue him. Each one of us will give you eleven hundred shekels of silver." Samson lies to her a couple of times then tells her the truth. "Then the Philistines seized him, gouged out his eyes and took him down to Gaza. Binding him with bronze shackles, they set him to grinding grain in the prison. But the hair on his head began to grow again after it had been shaved."

"Now the rulers of the Philistines assembled to offer a great sacrifice to Dagon their god and to celebrate, saying, "Our god has delivered Samson, our enemy, into our hands." And they brought Samson out to entertain each other. But Samson prayed, "O Lord, remember me" and he pushed the columns holding up the Temple and killed everyone there.

The story does not call Delilah a Philistine. The valley of Sorek was Danite territory that had been overrun by Philistines, so the population there would have been mixed. Delilah was likely an Israelite or the story would have said otherwise. The Philistines offered Delilah an enormous sum of money to betray Samson. Art has generally portrayed Delilah as a type of femme fatale, but the biblical term used (pattî) means to persuade with words. Delilah uses emotional blackmail and Samson's genuine love for her to betray him. No other Hebrew biblical hero is ever defeated by an Israelite woman. Samson does not suspect, perhaps because he cannot think of a woman as dangerous, but Delilah is determined, bold and very dangerous indeed. The entire Philistine army could not bring him down. Delilah did, but it was Samson himself who made that possible.[35]: 79–85

The Levite's concubine

The Levite's concubine in the book of Judges is "vulnerable as she is only a minor wife, a concubine".[2]: 173 She is one of the biblical nameless. Frymer-Kensky says this story is also an example of class intersecting with gender and power: when she is unhappy she runs home, only to have her father give her to another, the Levite. The Levite and his concubine travel to a strange town where they are vulnerable because they travel alone without extended family to rescue them; strangers attack. To protect the Levite, his host offers his daughter to the mob and the Levite sends out his concubine. Trible says "The story makes us realize that in those days men had ultimate powers of disposal over their women."[49]: 65–89 Frymer-Kensky says the scene is similar to one in the Sodom and Gomorrah story when Lot sent his daughters to the mob, but in Genesis the angels save them, and in the book of Judges God is no longer intervening. The concubine is raped to death.[2]: 173

The Levite butchers her body and uses it to rouse Israel against the tribe of Benjamin. Civil war follows nearly wiping out an entire tribe. To resuscitate it, hundreds of women are captured and forced into marriage. Fryman-Kensky says, "Horror follows horror."[2] The narrator caps off the story with "in those days there was no king in Israel and every man did as he pleased." The decline of Israel is reflected in the violence against women that takes place when government fails and social upheaval occurs.[56]: 14

According to Old Testament scholar Jerome Creach, some feminist critiques of Judges say the Bible gives tacit approval to violence against women by not speaking out against these acts.[56]: 14 Frymer-Kensky says leaving moral conclusions to the reader is a recognized method of writing called gapping used in many Bible stories.[2]: 395 Biblical scholar Michael Patrick O'Connor attributed acts of violence against women described in the Book of Judges to a period of crisis in the society of ancient Israel before the institution of kingship.[57] Yet others have alleged such problems are innate to patriarchy.[48]

Tamar, daughter-in-Law of Judah

In the Book of Genesis, Tamar is Judah's daughter-in-law. She was married to Judah's son Er, but Er died, leaving Tamar childless. Under levirate law, Judah's next son, Onan, was told to have sex with Tamar and give her a child, but when Onan slept with her, he "spilled his seed on the ground" rather than give her a child that would belong to his brother. Then Onan died too. "Judah then said to his daughter-in-law Tamar, 'Live as a widow in your father's household until my son Shelah grows up.' For he thought, 'He may die too, just like his brothers'." (Genesis 38:11) But when Shelah grew up, she was not given to him as his wife. One day Judah travels to town (Timnah) to shear his sheep. Tamar "took off her widow's clothes, covered herself with a veil to disguise herself, and then sat down at the entrance to Enaim, which is on the road to Timnah. When Judah saw her, he thought she was a prostitute, for she had covered her face. Not realizing that she was his daughter-in-law, he went over to her by the roadside and said, 'Come now, let me sleep with you'."(Genesis 38:14) He said he would give her something in return and she asked for a pledge, accepting his staff and his seal with its cord as earnest of later payment. So Judah slept with her and she became pregnant. Then she went home and put on her widow's weeds again. Months later when it was discovered she was pregnant, she was accused of prostitution (zonah), and was set to be burned. Instead, she sent Judah's pledge offerings to him saying "I am pregnant by the man who owns these." Judah recognized them and said, "She is more righteous than I, since I wouldn't give her to my son Shelah."

Jephthah's daughter

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Women_in_the_BibleText je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk