A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Gothic | |

|---|---|

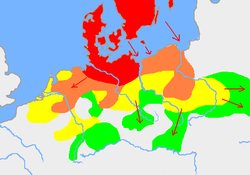

| Region | Oium, Dacia, Pannonia, Dalmatia, Italy, Gallia Narbonensis, Gallia Aquitania, Hispania, Crimea, North Caucasus |

| Era | attested 3rd–10th century; related dialects survived until 18th century in Crimea |

| Dialects |

|

| Gothic alphabet | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | got |

| ISO 639-3 | got |

| Glottolog | goth1244 |

| Linguasphere | 52-ADA |

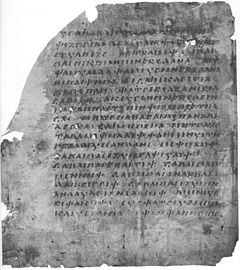

Gothic is an extinct East Germanic language that was spoken by the Goths. It is known primarily from the Codex Argenteus, a 6th-century copy of a 4th-century Bible translation, and is the only East Germanic language with a sizeable text corpus. All others, including Burgundian and Vandalic, are known, if at all, only from proper names that survived in historical accounts, and from loanwords in other, mainly Romance, languages.

As a Germanic language, Gothic is a part of the Indo-European language family. It is the earliest Germanic language that is attested in any sizable texts, but it lacks any modern descendants. The oldest documents in Gothic date back to the fourth century. The language was in decline by the mid-sixth century, partly because of the military defeat of the Goths at the hands of the Franks, the elimination of the Goths in Italy, and geographic isolation (in Spain, the Gothic language lost its last and probably already declining function as a church language when the Visigoths converted from Arianism to Nicene Christianity in 589).[3] The language survived as a domestic language in the Iberian peninsula (modern-day Spain and Portugal) as late as the eighth century. Gothic-seeming terms are found in manuscripts subsequent to this date, but these may or may not belong to the same language.

A language known as Crimean Gothic survived in the lower Danube area and in isolated mountain regions in Crimea as late as the second half of the 18th century. Lacking certain sound changes characteristic of Gothic, however, Crimean Gothic cannot be a lineal descendant of (Bible) Gothic (but possible of another East Germanic language, or alternatively be originally a West Germanic language).[4][5]

The existence of such early attested texts makes it a language of considerable interest in comparative linguistics.

History and evidence

Only a few documents in Gothic have survived – not enough for a complete reconstruction of the language. Most Gothic-language sources are translations or glosses of other languages (namely, Greek), so foreign linguistic elements most certainly influenced the texts. These are the primary sources:

- The largest body of surviving documentation consists of various codices, mostly from the sixth century, copying the Bible translation that was commissioned by the Arian bishop Ulfilas (Wulfila, 311–382), leader of a community of Visigothic Christians in the Roman province of Moesia (modern-day Serbia, Bulgaria/Romania). He commissioned a translation into the Gothic language of the Greek Bible, of which translation roughly three-quarters of the New Testament and some fragments of the Old Testament have survived. The extant translated texts, produced by several scholars, are collected in the following codices and in one inscription:

- Codex Argenteus (Uppsala), including the Speyer fragment: 188 leaves

- The best-preserved Gothic manuscript, dating from the sixth century, it was preserved and transmitted by northern Ostrogoths in modern-day Italy. It contains a large portion of the four gospels. Since it is a translation from Greek, the language of the Codex Argenteus is replete with borrowed Greek words and Greek usages. The syntax in particular is often copied directly from the Greek.

- Codex Ambrosianus (Milan) and the Codex Taurinensis (Turin): Five parts, totaling 193 leaves

- It contains scattered passages from the New Testament (including parts of the gospels and the Epistles), from the Old Testament (Nehemiah), and some commentaries known as Skeireins. The text likely had been somewhat modified by copyists.

- Codex Gissensis (Gießen): One leaf with fragments of Luke 23–24 (apparently a Gothic-Latin diglot) was found in an excavation in Arsinoë in Egypt in 1907 and was destroyed by water damage in 1945, after copies had already been made by researchers.

- Codex Carolinus (Wolfenbüttel): Four leaves, fragments of Romans 11–15 (a Gothic-Latin diglot).

- Codex Vaticanus Latinus 5750 (Vatican City): Three leaves, pages 57–58, 59–60, and 61–62 of the Skeireins. This is a fragment of Codex Ambrosianus E.

- Gothica Bononiensia (also known as the Codex Bononiensis), a palimpsest fragment, discovered in 2009, of two folios with what appears to be a sermon, containing besides non-biblical text a number of direct Bible quotes and allusions, both from previously attested parts of the Gothic Bible (the text is clearly taken from Ulfilas' translation) and from previously unattested ones (e.g., Psalms, Genesis).[6]

- Fragmenta Pannonica (also known as the Hács-Béndekpuszta fragments or Tabella Hungarica), which consist of fragments of a 1 mm thick lead plate with remnants of verses from the Gospels.

- The Mangup Graffiti: five inscriptions written in the Gothic Alphabet discovered in 2015 from the basilica church of Mangup, Crimea. The graffiti all date from the mid-9th century, making this the latest attestation of the Gothic Alphabet and the only one from outside Italy or Pannonia. The five texts include a quotation from the otherwise unattested Psalm 76 and some prayers; the language is not noticeably different from Wulfila's and only contains words known from other parts of the Gothic Bible.[7]

- A scattering of old documents: two deeds (the Naples and Arezzo deeds, on papyri), alphabets (in the Gothica Vindobonensia and the Gothica Parisina), a calendar (in the Codex Ambrosianus A), glosses found in a number of manuscripts and a few runic inscriptions (between three and 13) that are known or suspected to be Gothic: some scholars believe that these inscriptions are not at all Gothic.[8] Krause thought that several names in an Indian inscription were possibly Gothic.[9]

Reports of the discovery of other parts of Ulfilas' Bible have not been substantiated. Heinrich May in 1968 claimed to have found in England twelve leaves of a palimpsest containing parts of the Gospel of Matthew.

Only fragments of the Gothic translation of the Bible have been preserved. The translation was apparently done in the Balkans region by people in close contact with Greek Christian culture. The Gothic Bible apparently was used by the Visigoths in southern France until the loss of Visigothic France at the start of the 6th century,[10] in Visigothic Iberia until about 700, and perhaps for a time in Italy, the Balkans, and Ukraine until at least the mid-9th century. During the extermination of Arianism, Trinitarian Christians probably overwrote many texts in Gothic as palimpsests, or alternatively collected and burned Gothic documents. Apart from biblical texts, the only substantial Gothic document that still exists – and the only lengthy text known to have been composed originally in the Gothic language – is the Skeireins, a few pages of commentary on the Gospel of John.[citation needed]

Very few medieval secondary sources make reference to the Gothic language after about 800. In De incrementis ecclesiae Christianae (840–842), Walafrid Strabo, a Frankish monk who lived in Swabia, writes of a group of monks who reported that even then certain peoples in Scythia (Dobruja), especially around Tomis, spoke a sermo Theotiscus ('Germanic language'), the language of the Gothic translation of the Bible, and that they used such a liturgy.[11]

Many writers of the medieval texts that mention the Goths used the word Goths to mean any Germanic people in eastern Europe (such as the Varangians), many of whom certainly did not use the Gothic language as known from the Gothic Bible. Some writers even referred to Slavic-speaking people as "Goths". However, it is clear from Ulfilas' translation that – despite some puzzles – the Gothic language belongs with the Germanic language-group, not with Slavic.

Generally, the term "Gothic language" refers to the language of Ulfilas, but the attestations themselves date largely from the 6th century, long after Ulfilas had died.[citation needed]

Alphabet and transliteration

This article should specify the language of its non-English content, using {{lang}}, {{transliteration}} for transliterated languages, and {{IPA}} for phonetic transcriptions, with an appropriate ISO 639 code. Wikipedia's multilingual support templates may also be used. (June 2022) |

A few Gothic runic inscriptions were found across Europe, but due to early Christianization of the Goths, the Runic writing was quickly replaced by the newly invented Gothic alphabet.

Ulfilas's Gothic, as well as that of the Skeireins and various other manuscripts, was written using an alphabet that was most likely invented by Ulfilas himself for his translation. Some scholars (such as Braune) claim that it was derived from the Greek alphabet only while others maintain that there are some Gothic letters of Runic or Latin origin.

A standardized system is used for transliterating Gothic words into the Latin script. The system mirrors the conventions of the native alphabet, such as writing long /iː/ as ei. The Goths used their equivalents of e and o alone only for long higher vowels, using the digraphs ai and au (much as in French) for the corresponding short or lower vowels. There are two variant spelling systems: a "raw" one that directly transliterates the original Gothic script and a "normalized" one that adds diacritics (macrons and acute accents) to certain vowels to clarify the pronunciation or, in certain cases, to indicate the Proto-Germanic origin of the vowel in question. The latter system is usually used in the academic literature.

The following table shows the correspondence between spelling and sound for vowels:

| Gothic letter or digraph |

Roman equivalent |

"Normalised" transliteration |

Sound | Normal environment of occurrence (in native words) |

Paradigmatically alternating sound in other environments |

Proto-Germanic origin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 𐌰 | a | a | /a/ | Everywhere | — | /ɑ/ |

| ā | /aː/ | Before /h/, /hʷ/ | Does not occur | /ãː/ (before /h/) | ||

| 𐌰𐌹 | ai | aí | /ɛ/ | Before /h/, /hʷ/, /r/ | i /i/ | /e/, /i/ |

| ai | /ɛː/ | Before vowels | ē /eː/ | /ɛː/, /eː/ | ||

| ái | /ɛː/ | Not before vowels | aj /aj/ | /ɑi/ | ||

| 𐌰𐌿 | au | aú | /ɔ/ | Before /h/, /hʷ/, /r/ | u /u/ | /u/ |

| au | /ɔː/ | Before vowels | ō /oː/ | /ɔː/ | ||

| áu | /ɔː/ | Not before vowels | aw /aw/ | /ɑu/ | ||

| 𐌴 | e | ē | /eː/ | Not before vowels | ai /ɛː/ | /ɛː/, /eː/ |

| 𐌴𐌹 | ei | ei | /iː/ | Everywhere | — | /iː/; /ĩː/ (before /h/) |

| 𐌹 | i | i | /i/ | Everywhere except before /h/, /hʷ/, /r/ | aí /ɛ/ | /e/, /i/ |

| 𐌹𐌿 | iu | iu | /iu/ | Not before vowels | iw /iw/ | /eu/ (and its allophone ) |

| 𐍉 | o | ō | /oː/ | Not before vowels | au /ɔː/ | /ɔː/ |

| 𐌿 | u | u | /u/ | Everywhere except before /h/, /hʷ/, /r/ | aú /ɔ/ | /u/ |

| ū | /uː/ | Everywhere | — | /uː/; /ũː/ (before /h/) |

Notes:

- This "normalised transliteration" system devised by Jacob Grimm is used in some modern editions of Gothic texts and in studies of Common Germanic. It signals distinctions not made by Ulfilas in his alphabet. Rather, they reflect various origins in Proto-Germanic. Thus,

- aí is used for the sound derived from the Proto-Germanic short vowels e and i before /h/ and /r/.

- ái is used for the sound derived from the Proto-Germanic diphthong ai. Some scholars have considered this sound to have remained as a diphthong in Gothic. However, Ulfilas was highly consistent in other spelling inventions, which makes it unlikely that he assigned two different sounds to the same digraph. Furthermore, he consistently used the digraph to represent Greek αι, which was then certainly a monophthong. A monophthongal value is accepted by Eduard Prokosch in his influential A Common Germanic Grammar.[12] It had earlier been accepted by Joseph Wright but only in an appendix to his Grammar of the Gothic Language.[13]

- ai is used for the sound derived from the Common Germanic long vowel ē before a vowel.

- áu is used for the sound derived from Common Germanic diphthong au. It cannot be related to a Greek digraph, since αυ then represented a sequence of a vowel and a spirant (fricative) consonant, which Ulfilas transcribed as aw in representing Greek words. Nevertheless, the argument based on simplicity is accepted by some influential scholars.[12][13]

- The "normal environment of occurrence" refers to native words. In foreign words, these environments are often greatly disturbed. For example, the short sounds /ɛ/ and /i/ alternate in native words in a nearly allophonic way, with /ɛ/ occurring in native words only before the consonants /h/, /hʷ/, /r/ while /i/ occurs everywhere else (nevertheless, there are a few exceptions such as /i/ before /r/ in hiri, /ɛ/ consistently in the reduplicating syllable of certain past-tense verbs regardless of the following consonant, which indicate that these sounds had become phonemicized). In foreign borrowings, however, /ɛ/ and /i/ occur freely in all environments, reflecting the corresponding vowel quality in the source language.

- Paradigmatic alterations can occur either intra-paradigm (between two different forms within a specific paradigm) or cross-paradigm (between the same form in two different paradigms of the same class). Examples of intra-paradigm alternation are gawi /ɡa.wi/ "district (nom.)" vs. gáujis /ɡɔː.jis/ "district (gen.)"; mawi /ma.wi/ "maiden (nom.)" vs. máujōs /mɔː.joːs/ "maiden (gen.)"; þiwi /θi.wi/ "maiden (nom.)" vs. þiujōs /θiu.joːs/ "maiden (gen.)"; taui /tɔː.i/ "deed (nom.)" vs. tōjis /toː.jis/ "deed (gen.)"; náus /nɔːs/ "corpse (nom.)" vs. naweis /na.wiːs/ "corpses (nom.)"; triu /triu/?? "tree (nom.)" vs. triwis /tri.wis/ "tree (gen.)"; táujan /tɔː.jan/ "to do" vs. tawida /ta.wi.ða/ "I/he did"; stōjan /stoː.jan/ "to judge" vs. stauida /stɔː.i.ða/ "I/he judged". Examples of cross-paradigm alternation are Class IV verbs qiman /kʷiman/ "to come" vs. baíran /bɛran/ "to carry, to bear", qumans /kʷumans/ "(having) come" vs. baúrans /bɔrans/ "(having) carried"; Class VIIb verbs lētan /leː.tan/ "to let" vs. saian /sɛː.an/ "to sow" (note similar preterites laílōt /lɛ.loːt/ "I/he let", saísō /sɛ.soː/ "I/he sowed"). A combination of intra- and cross-paradigm alternation occurs in Class V sniwan /sni.wan/ "to hasten" vs. snáu /snɔː/ "I/he hastened" (expected *snaw, compare qiman "to come", qam "I/he came").

- The carefully maintained alternations between iu and iw suggest that iu may have been something other than /iu/. Various possibilities have been suggested (for example, high central or high back unrounded vowels, such as ); under these theories, the spelling of iu is derived from the fact that the sound alternates with iw before a vowel, based on the similar alternations au and aw. The most common theory, however, simply posits /iu/ as the pronunciation of iu.

- Macrons represent long ā and ū (however, long i appears as ei, following the representation used in the native alphabet). Macrons are often also used in the case of ē and ō; however, they are sometimes omitted since these vowels are always long. Long ā occurs only before the consonants /h/, /hʷ/ and represents Proto-Germanic nasalized /ãː(h)/ < earlier /aŋ(h)/; non-nasal /aː/ did not occur in Proto-Germanic. It is possible that the Gothic vowel still preserved the nasalization, or else that the nasalization was lost but the length distinction kept, as has happened with Lithuanian ą. Non-nasal /iː/ and /uː/ occurred in Proto-Germanic, however, and so long ei and ū occur in all contexts. Before /h/ and /hʷ/, long ei and ū could stem from either non-nasal or nasal long vowels in Proto-Germanic; it is possible that the nasalization was still preserved in Gothic but not written.

The following table shows the correspondence between spelling and sound for consonants:

| Gothic Letter | Roman | Sound (phoneme) | Sound (allophone) | Environment of occurrence | Paradigmatically alternating sound, in other environments | Proto-Germanic origin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 𐌱 | b | /b/ | [b] | Word-initially; after a consonant | – | /b/ |

| [β] | After a vowel, before a voiced sound | /ɸ/ (after a vowel, before an unvoiced sound) | ||||

| 𐌳 | d | /d/ | [d] | Word-initially; after a consonant | – | /d/ |

| [ð] | After a vowel, before a voiced sound | /θ/ (after a vowel, before an unvoiced sound) | ||||

| 𐍆 | f | /ɸ/ | [ɸ] | Everywhere except before a voiced consonant | /b/ | /ɸ/; /b/ |

| 𐌲 | g | /ɡ/ | [ɡ] | Word-initially; after a consonant | – | /g/ |

| [ɣ] | After a vowel, before a voiced sound | /ɡ/ (after a vowel, not before a voiced sound) | ||||

| [x] | After a vowel, not before a voiced sound | /ɡ/ (after a vowel, before a voiced sound) | ||||

| /n/ | [ŋ] | Before k /k/, g /ɡ/ , gw /ɡʷ/ (such usage influenced by Greek, compare gamma) |

– | /n/ | ||

| gw | /ɡʷ/ | [ɡʷ] | After g /n/ | – | /ɡʷ/ | |

| 𐌷 | h | /h/ | [h] | Everywhere except before a voiced consonant | /ɡ/ | /x/ |

| 𐍈 | ƕ | /hʷ/ | [hʷ] | Everywhere except before a voiced consonant | – | /xʷ/ |

| 𐌾 | j | /j/ | [j] | Everywhere | – | /j/ |

| 𐌺 | k | /k/ | [k] | Everywhere except before a voiced consonant | – | /k/ |

| 𐌻 | l | /l/ | [l] | Everywhere | – | /l/ |

| 𐌼 | m | /m/ | [m] | Everywhere | – | /m/ |

| 𐌽 | n | /n/ | [n] | Everywhere | – | /n/ |

| 𐍀 | p | /p/ | [p] | Everywhere except before a voiced consonant | – | /p/ |

| 𐌵 | q | /kʷ/ | [kʷ] | Everywhere except before a voiced consonant | – | /kʷ/ |

| 𐍂 | r | /r/ | [r] | Everywhere | – | /r/ |

| 𐍃 | s | /s/ | [s] | Everywhere except before a voiced consonant | /z/ | /s/; /z/ |

| 𐍄 | t | /t/ | [t] | Everywhere except before a voiced consonant | – | /t/ |

| 𐌸 | þ | /θ/ | [θ] | Everywhere except before a voiced consonant | /d/ | /θ/; /d/ |

| 𐍅 | w | /w/ | [w] | Everywhere | – | ?pojem= |

| 𐌶 | z | /z/ | [z] | After a vowel, before a voiced sound | /s/ | /z/ |

- /hʷ/, which is written with a single character in the native alphabet, is transliterated using the symbol ƕ, which is used only in transliterating Gothic.

- /kʷ/ is similarly written with a single character in the native alphabet and is transliterated q (with no following u).

- /ɡʷ/, however, is written with two letters in the native alphabet and hence 𐌲𐍅 (gw). The lack of a single letter to represent this sound may result from its restricted distribution (only after /n/) and its rarity.

- /θ/ is written þ, similarly to other Germanic languages.

- Although is the allophone of /n/ occurring before /ɡ/ and /k/, it is written g, following the native alphabet convention (which, in turn, follows Greek usage), which leads to occasional ambiguities, e.g. saggws "song" but triggws "faithful" (compare English "true").

Phonology

It is possible to determine more or less exactly how the Gothic of Ulfilas was pronounced, primarily through comparative phonetic reconstruction. Furthermore, because Ulfilas tried to follow the original Greek text as much as possible in his translation, it is known that he used the same writing conventions as those of contemporary Greek. Since the Greek of that period is well documented, it is possible to reconstruct much of Gothic pronunciation from translated texts. In addition, the way in which non-Greek names are transcribed in the Greek Bible and in Ulfilas's Bible is very informative.