A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Literature | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Oral literature | ||||||

| Major written forms | ||||||

|

||||||

| Prose genres | ||||||

|

||||||

| Poetry genres | ||||||

|

||||||

| Dramatic genres | ||||||

| History | ||||||

| Lists and outlines | ||||||

| Theory and criticism | ||||||

|

| ||||||

English literature is literature written in the English language from the English-speaking world. The English language has developed over the course of more than 1,400 years.[1] The earliest forms of English, a set of Anglo-Frisian dialects brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon invaders in the fifth century, are called Old English. Beowulf is the most famous work in Old English, and has achieved national epic status in England, despite being set in Scandinavia. However, following the Norman conquest of England in 1066, the written form of the Anglo-Saxon language became less common. Under the influence of the new aristocracy, French became the standard language of courts, parliament, and polite society.[2] The English spoken after the Normans came is known as Middle English. This form of English lasted until the 1470s, when the Chancery Standard (late Middle English), a London-based form of English, became widespread. Geoffrey Chaucer (1343–1400), author of The Canterbury Tales, was a significant figure in the development of the legitimacy of vernacular Middle English at a time when the dominant literary languages in England were still French and Latin. The invention of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg in 1439 also helped to standardise the language, as did the King James Bible (1611),[3] and the Great Vowel Shift.[4]

Poet and playwright William Shakespeare (1564–1616) is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and one of the world's greatest dramatists.[5][6][7] His plays have been translated into every major living language and are performed more often than those of any other playwright.[8] In the nineteenth century Sir Walter Scott's historical romances inspired a generation of painters, composers, and writers throughout Europe.[9]

The English language spread throughout the world with the development of the British Empire between the late 16th and early 18th centuries. At its height, it was the largest empire in history.[10] By 1913, the British Empire held sway over 412 million people, 23% of the world population at the time,[11] During the nineteenth and twentieth centuries these colonies and the USA started to produce their own significant literary traditions in English. Cumulatively, over the period of 1907 to the present, numerous writers from Great Britain, both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland, the US, and former British colonies have received the Nobel Prize for works in the English language, more than in any language.

Old English literature (c. 450–1066)

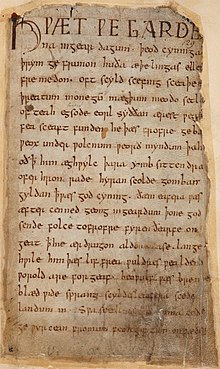

Old English literature, or Anglo-Saxon literature, encompasses the surviving literature written in Old English in Anglo-Saxon England, in the period after the settlement of the Saxons and other Germanic tribes in England (Jutes and the Angles) c. 450, after the withdrawal of the Romans, and "ending soon after the Norman Conquest" in 1066.[12] These works include genres such as epic poetry, hagiography, sermons, Bible translations, legal works, chronicles and riddles.[13] In all there are about 400 surviving manuscripts from the period.[13]

Widsith, which appears in the Exeter Book of the late 10th century, gives a list of kings of tribes ordered according to their popularity and impact on history, with Attila King of the Huns coming first, followed by Eormanric of the Ostrogoths.[14]: 187 It may also be the oldest extant work that tells the Battle of the Goths and Huns, which is also told in such later Scandinavian works as Hervarar's saga and Gesta Danorum.[14]: 179 Lotte Hedeager argues that the work is far older, however, and that it likely dates back to the late 6th or early 7th century, citing the author's knowledge of historical details and accuracy as proof of its authenticity.[14]: 184–86 She does note, however, that some authors, such as John Niles, have argued the work was invented in the 10th century.[14]: 181–84

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is a collection of annals in Old English, from the 9th century, that chronicles the history of the Anglo-Saxons.[15] The poem Battle of Maldon also deals with history. This is a work of uncertain date, celebrating the Battle of Maldon of 991, at which the Anglo-Saxons failed to prevent a Viking invasion.[16]

Oral tradition was very strong in early English culture and most literary works were written to be performed.[17][18] Epic poems were very popular, and some, including Beowulf, have survived to the present day. Beowulf is the most famous work in Old English, and has achieved national epic status in England, despite being set in Scandinavia. The only surviving manuscript is the Nowell Codex, the precise date of which is debated, but most estimates place it close to the year 1000. Beowulf is the conventional title,[19] and its composition is dated between the 8th[20][21] and the early 11th century.[22]

Nearly all Anglo-Saxon authors are anonymous: twelve are known by name from medieval sources, but only four of those are known by their vernacular works with any certainty: Cædmon, Bede, Alfred the Great, and Cynewulf. Cædmon is the earliest English poet whose name is known,[23][pages needed] and his only known surviving work Cædmon's Hymn probably dates from the late 7th century. The poem is one of the earliest attested examples of Old English and is, with the runic Ruthwell Cross and Franks Casket inscriptions, one of three candidates for the earliest attested example of Old English poetry. It is also one of the earliest recorded examples of sustained poetry in a Germanic language. The poem, The Dream of the Rood, was inscribed upon the Ruthwell Cross.[23][pages needed]

Two Old English poems from the late 10th century are The Wanderer and The Seafarer. [24] Both have a religious theme, and Richard Marsden describes The Seafarer as "an exhortatory and didactic poem, in which the miseries of winter seafaring are used as a metaphor for the challenge faced by the committed Christian ".[25]

Classical antiquity was not forgotten in Anglo-Saxon England, and several Old English poems are adaptations of late classical philosophical texts. The longest is King Alfred's (849–899) 9th-century translation of Boethius' Consolation of Philosophy.[26]

Middle English literature (1066–1500)

After the Norman conquest of England in 1066, the written form of the Anglo-Saxon language became less common. Under the influence of the new aristocracy, French became the standard language of courts, parliament, and polite society. As the invaders integrated, their language and literature mingled with that of the natives, and the Norman dialects of the ruling classes became Anglo-Norman. From then until the 12th century, Anglo-Saxon underwent a gradual transition into Middle English. Political power was no longer in English hands, so that the West Saxon literary language had no more influence than any other dialect and Middle English literature was written in many dialects that corresponded to the region, history, culture, and background of individual writers.[2]

In this period religious literature continued to enjoy popularity and Hagiographies were written, adapted and translated: for example, The Life of Saint Audrey, Eadmer's (c. 1060 – c. 1126).[27] At the end of the 12th century, Layamon in Brut adapted the Norman-French of Wace to produce the first English-language work to present the legends of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table.[28] It was also the first historiography written in English since the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle.

Middle English Bible translations, notably Wycliffe's Bible, helped to establish English as a literary language. Wycliffe's Bible is the name now given to a group of Bible translations into Middle English that were made under the direction of, or at the instigation of, John Wycliffe. They appeared between about 1382 and 1395.[29] These Bible translations were the chief inspiration and cause of the Lollard movement, a pre-Reformation movement that rejected many of the teachings of the Roman Catholic Church.

Another literary genre, that of Romances, appears in English from the 13th century, with King Horn and Havelock the Dane, based on Anglo-Norman originals such as the Romance of Horn (c. 1170),[30] but it was in the 14th century that major writers in English first appeared. These were William Langland, Geoffrey Chaucer and the so-called Pearl Poet, whose most famous work is Sir Gawain and the Green Knight.[31]

Langland's Piers Plowman (written c. 1360–87) or Visio Willelmi de Petro Plowman (William's Vision of Piers Plowman) is a Middle English allegorical narrative poem, written in unrhymed alliterative verse.[32]

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight is a late 14th-century Middle English alliterative romance. It is one of the better-known Arthurian stories of an established type known as the "beheading game". Developing from Welsh, Irish and English tradition, Sir Gawain highlights the importance of honour and chivalry. Preserved in the same manuscript with Sir Gawayne were three other poems, now generally accepted as the work of the same author, including an intricate elegiac poem, Pearl.[33] The English dialect of these poems from the Midlands is markedly different from that of the London-based Chaucer and, though influenced by French in the scenes at court in Sir Gawain, there are in the poems also many dialect words, often of Scandinavian origin, that belonged to northwest England.[33]

Middle English lasted until the 1470s, when the Chancery Standard, a London-based form of English, became widespread and the printing press started to standardise the language. Chaucer is best known today for The Canterbury Tales. This is a collection of stories written in Middle English (mostly in verse although some are in prose), that are presented as part of a story-telling contest by a group of pilgrims as they travel together from Southwark to the shrine of St Thomas Becket at Canterbury Cathedral. Chaucer is a significant figure in the development of the legitimacy of the vernacular, Middle English, at a time when the dominant literary languages in England were still French and Latin.

At this time, literature in England was being written in various languages, including Latin, Norman-French, and English: the multilingual nature of the audience for literature in the 14th century is illustrated by the example of John Gower (c. 1330–1408). A contemporary of William Langland and a personal friend of Chaucer, Gower is remembered primarily for three major works: the Mirroir de l'Omme, Vox Clamantis, and Confessio Amantis, three long poems written in Anglo-Norman, Latin and Middle English respectively, which are united by common moral and political themes.[34]

Significant religious works were also created in the 14th century, including those of Julian of Norwich (c. 1342 – c. 1416) and Richard Rolle. Julian's Revelations of Divine Love (about 1393) is believed to be the first published book written by a woman in the English language.[35]

A major work from the 15th century is Le Morte d'Arthur by Sir Thomas Malory, which was printed by Caxton in 1485.[36] This is a compilation of some French and English Arthurian romances, and was among the earliest books printed in England. It was popular and influential in the later revival of interest in the Arthurian legends.[37]

Medieval theatre

In the Middle Ages, drama in the vernacular languages of Europe may have emerged from enactments of the liturgy. Mystery plays were presented in the porches of cathedrals or by strolling players on feast days. Miracle and mystery plays, along with morality plays (or "interludes"), later evolved into more elaborate forms of drama, such as was seen on the Elizabethan stages. Another form of medieval theatre was the mummers' plays, a form of early street theatre associated with the Morris dance, concentrating on themes such as Saint George and the Dragon and Robin Hood. These were folk tales re-telling old stories, and the actors travelled from town to town performing these for their audiences in return for money and hospitality.[38]

Mystery plays and miracle plays are among the earliest formally developed plays in medieval Europe. Medieval mystery plays focused on the representation of Bible stories in churches as tableaux with accompanying antiphonal song. They developed from the 10th to the 16th century, reaching the height of their popularity in the 15th century before being rendered obsolete by the rise of professional theatre.[39]

There are four complete or nearly complete extant English biblical collections of plays from the late medieval period. The most complete is the York cycle of 48 pageants. They were performed in the city of York, from the middle of the 14th century until 1569.[40] Besides the Middle English drama, there are three surviving plays in Cornish known as the Ordinalia.[41][42]

Having grown out of the religiously based mystery plays of the Middle Ages, the morality play is a genre of medieval and early Tudor theatrical entertainment, which represented a shift towards a more secular base for European theatre.[43] Morality plays are a type of allegory in which the protagonist is met by personifications of various moral attributes who try to prompt him to choose a godly life over one of evil. The plays were most popular in Europe during the 15th and 16th centuries.[44]

The Somonyng of Everyman (The Summoning of Everyman) (c. 1509–1519), usually referred to simply as Everyman, is a late 15th-century English morality play. Like John Bunyan's allegory Pilgrim's Progress (1678), Everyman examines the question of Christian salvation through the use of allegorical characters.[45]

English Renaissance (1500–1660)

The English Renaissance as a part of the Northern Renaissance was a cultural and artistic movement in England dating from the late 15th to the 17th century.[46] It is associated with the pan-European Renaissance that is usually regarded as beginning in Italy in the late 14th century. Like most of northern Europe, England saw little of these developments until more than a century later — Renaissance style and ideas were slow in penetrating England. Many scholars see the beginnings of the English Renaissance during the reign of Henry VIII[47] and the Elizabethan era in the second half of the 16th century is usually regarded as the height of the English Renaissance.[46][48]

The influence of the Italian Renaissance can also be found in the poetry of Thomas Wyatt (1503–1542), one of the earliest English Renaissance poets. He was responsible for many innovations in English poetry, and alongside Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey (1516/1517–1547) introduced the sonnet from Italy into England in the early 16th century.[49][50][51] After William Caxton introduced the printing press in England in 1476, vernacular literature flourished.[36] The Reformation inspired the production of vernacular liturgy which led to the Book of Common Prayer (1549), a lasting influence on literary language.

Elizabethan period (1558–1603)

Poetry

Edmund Spenser (c. 1552–1599) was one of the most important poets of the Elizabethan period, author of The Faerie Queene (1590 and 1596), an epic poem and fantastical allegory celebrating the Tudor dynasty and Elizabeth I. Another major figure, Sir Philip Sidney (1554–1586), was an English poet, whose works include Astrophel and Stella, The Defence of Poetry, and The Countess of Pembroke's Arcadia. Poems intended to be set to music as songs, such as those by Thomas Campion (1567–1620), became popular as printed literature was disseminated more widely in households. John Donne was another important figure in Elizabethan poetry (see Jacobean poetry below).

Drama

Among the earliest Elizabethan plays are Gorboduc (1561) by Sackville and Norton, and Thomas Kyd's (1558–1594) The Spanish Tragedy (1592). Gorboduc is notable especially as the first verse drama in English to employ blank verse, and for the way it developed elements, from the earlier morality plays and Senecan tragedy, in the direction which would be followed by later playwrights.[52] The Spanish Tragedy[53] is an Elizabethan tragedy written by Thomas Kyd between 1582 and 1592, which was popular and influential in its time, and established a new genre in English literature theatre, the revenge play.[54]

William Shakespeare (1564–1616) stands out in this period as a poet and playwright as yet unsurpassed. Shakespeare wrote plays in a variety of genres, including histories (such as Richard III and Henry IV), tragedies (such as Hamlet, Othello, and Macbeth) comedies (such as Midsummer Night's Dream, As You Like It, and Twelfth Night) and the late romances, or tragicomedies. Shakespeare's career continues in the Jacobean period.

Other important figures in Elizabethan theatre include Christopher Marlowe, and Ben Jonson, Thomas Dekker, John Fletcher and Francis Beaumont.

Jacobean period (1603–1625)

Drama

In the early 17th century Shakespeare wrote the so-called "problem plays", as well as a number of his best known tragedies, including Macbeth and King Lear.[55] In his final period, Shakespeare turned to romance or tragicomedy and completed three more major plays, including The Tempest. Less bleak than the tragedies, these four plays are graver in tone than the comedies of the 1590s, but they end with reconciliation and the forgiveness of potentially tragic errors.[56]

After Shakespeare's death, the poet and dramatist Ben Jonson (1572–1637) was the leading literary figure of the Jacobean era. Jonson's aesthetics hark back to the Middle Ages and his characters embody the theory of humours, which was based on contemporary medical theory.[57] Jonson's comedies include Volpone (1605 or 1606) and Bartholomew Fair (1614). Others who followed Jonson's style include Beaumont and Fletcher, who wrote the popular comedy, The Knight of the Burning Pestle (probably 1607–08), a satire of the rising middle class.[58]

Another popular style of theatre during Jacobean times was the revenge play, which was popularized in the Elizabethan era by Thomas Kyd (1558–1594), and then further developed later by John Webster (?1578–?1632), The White Devil (1612) and The Duchess of Malfi (1613). Other revenge tragedies include The Changeling written by Thomas Middleton and William Rowley.[59]

Poetry

George Chapman (c. 1559 – c. 1634) is remembered chiefly for his famous translation in 1616 of Homer's Iliad and Odyssey into English verse.[60] This was the first ever complete translations of either poem into the English language. The translation had a profound influence on English literature and inspired John Keats's famous sonnet "On First Looking into Chapman's Homer" (1816).

Shakespeare popularized the English sonnet, which made significant changes to Petrarch's model. A collection of 154 by sonnets, dealing with themes such as the passage of time, love, beauty and mortality, were first published in a 1609 quarto.

Besides Shakespeare and Ben Jonson, the major poets of the early 17th century included the Metaphysical poets: John Donne (1572–1631), George Herbert (1593–1633), Henry Vaughan, Andrew Marvell, and Richard Crashaw.[61] Their style was characterized by wit and metaphysical conceits, that is far-fetched or unusual similes or metaphors.[62]

Prose

The most important prose work of the early 17th century was the King James Bible. This, one of the most massive translation projects in the history of English up to this time, was started in 1604 and completed in 1611. This represents the culmination of a tradition of Bible translation into English that began with the work of William Tyndale, and it became the standard Bible of the Church of England.[63]

Late Renaissance (1625–1660)

Poetry

The Metaphysical poets John Donne (1572–1631) and George Herbert (1593–1633) were still alive after 1625, and later in the 17th century a second generation of metaphysical poets were writing, including Richard Crashaw (1613–1649), Andrew Marvell (1621–1678), Thomas Traherne (1636 or 1637–1674) and Henry Vaughan (1622–1695). The Cavalier poets were another important group of 17th-century poets, who came from the classes that supported King Charles I during the English Civil War (1642–51). (King Charles reigned from 1625 and was executed in 1649). The best known of the Cavalier poets are Robert Herrick, Richard Lovelace, Thomas Carew and Sir John Suckling. They "were not a formal group, but all were influenced by" Ben Jonson. Most of the Cavalier poets were courtiers, with notable exceptions. For example, Robert Herrick was not a courtier, but his style marks him as a Cavalier poet. Cavalier works make use of allegory and classical allusions, and are influenced by Roman authors Horace, Cicero and Ovid. John Milton (1608–1674) "was the last great poet of the English Renaissance"[64] and published a number of works before 1660, including L'Allegro,1631; Il Penseroso, 1634; Comus (a masque), 1638; and Lycidas, (1638). However, his major epic works, including Paradise Lost (1667) were published in the Restoration period.

Restoration Age (1660–1700)

This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2016) |

Restoration literature includes both Paradise Lost and the Earl of Rochester's Sodom, the sexual comedy of The Country Wife and the moral wisdom of Pilgrim's Progress. It saw Locke's Two Treatises on Government, the founding of the Royal Society, the experiments and the holy meditations of Robert Boyle, the hysterical attacks on theatres from Jeremy Collier, the pioneering of literary criticism from Dryden, and the first newspapers. The official break in literary culture caused by censorship and radically moralist standards under Cromwell's Puritan regime created a gap in literary tradition, allowing a seemingly fresh start for all forms of literature after the Restoration. During the Interregnum, the royalist forces attached to the court of Charles I went into exile with the twenty-year-old Charles II. The nobility who travelled with Charles II were therefore lodged for over a decade in the midst of the continent's literary scene.

Poetry

John Milton, one of the greatest English poets, wrote at this time of religious flux and political upheaval. Milton is best known for his epic poem Paradise Lost (1667). Among other important poems include L'Allegro, 1631, Il Penseroso 1634, Comus (a masque), 1638 and Lycidas. Milton's poetry and prose reflect deep personal convictions, a passion for freedom and self-determination, and the urgent issues and political turbulence of his day. His celebrated Areopagitica, written in condemnation of pre-publication censorship, is among history's most influential and impassioned defenses of free speech and freedom of the press.[65] The largest and most important poetic form of the era was satire. In general, publication of satire was done anonymously, as there were great dangers in being associated with a satire.

John Dryden (1631–1700) was an influential English poet, literary critic, translator, and playwright who dominated the literary life of Restoration England to such a point that the period came to be known in literary circles as the Age of Dryden. He established the heroic couplet as a standard form of English poetry. Dryden's greatest achievements were in satiric verse in works like the mock-heroic MacFlecknoe (1682).[66] Alexander Pope (1688–1744) was heavily influenced by Dryden, and often borrowed from him; other writers in the 18th century were equally influenced by both Dryden and Pope.

Prose

Prose in the Restoration period is dominated by Christian religious writing, but the Restoration also saw the beginnings of two genres that would dominate later periods, fiction and journalism. Religious writing often strayed into political and economic writing, just as political and economic writing implied or directly addressed religion. The Restoration was also the time when John Locke wrote many of his philosophical works. His two Treatises on Government, which later inspired the thinkers in the American Revolution. The Restoration moderated most of the more strident sectarian writing, but radicalism persisted after the Restoration. Puritan authors such as John Milton were forced to retire from public life or adapt, and those authors who had preached against monarchy and who had participated directly in the regicide of Charles I were partially suppressed. Consequently, violent writings were forced underground, and many of those who had served in the Interregnum attenuated their positions in the Restoration. John Bunyan stands out beyond other religious authors of the period. Bunyan's The Pilgrim's Progress is an allegory of personal salvation and a guide to the Christian life.

During the Restoration period, the most common manner of getting news would have been a broadsheet publication. A single, large sheet of paper might have a written, usually partisan, account of an event.

It is impossible to satisfactorily date the beginning of the novel in English. However, long fiction and fictional biographies began to distinguish themselves from other forms in England during the Restoration period. An existing tradition of Romance fiction in France and Spain was popular in England. One of the most significant figures in the rise of the novel in the Restoration period is Aphra Behn, author of Oroonoko (1688), who was not only the first professional female novelist, but she may be among the first professional novelists of either sex in England.

Drama

As soon as the previous Puritan regime's ban on public stage representations was lifted, drama recreated itself quickly and abundantly.[67] The most famous plays of the early Restoration period are the unsentimental or "hard" comedies of John Dryden, William Wycherley, and George Etherege, which reflect the atmosphere at Court, and celebrate an aristocratic macho lifestyle of unremitting sexual intrigue and conquest. After a sharp drop in both quality and quantity in the 1680s, the mid-1690s saw a brief second flowering of the drama, especially comedy. Comedies like William Congreve's The Way of the World (1700), and John Vanbrugh's The Relapse (1696) and The Provoked Wife (1697) were "softer" and more middle-class in ethos, very different from the aristocratic extravaganza twenty years earlier, and aimed at a wider audience.

18th century

Augustan literature (1700–1745)

This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2016) |

During the 18th century literature reflected the worldview of the Age of Enlightenment (or Age of Reason): a rational and scientific approach to religious, social, political, and economic issues that promoted a secular view of the world and a general sense of progress and perfectibility. Led by the philosophers who were inspired by the discoveries of the previous century by people like Isaac Newton and the writings of Descartes, John Locke and Francis Bacon. They sought to discover and to act upon universally valid principles governing humanity, nature, and society. They variously attacked spiritual and scientific authority, dogmatism, intolerance, censorship, and economic and social restraints. They considered the state the proper and rational instrument of progress. The extreme rationalism and skepticism of the age led naturally to deism and also played a part in bringing the later reaction of romanticism. The Encyclopédie of Denis Diderot epitomized the spirit of the age.

The term Augustan literature derives from authors of the 1720s and 1730s themselves, who responded to a term that George I of Great Britain preferred for himself. While George I meant the title to reflect his might, they instead saw in it a reflection of Ancient Rome's transition from rough and ready literature to highly political and highly polished literature. It is an age of exuberance and scandal, of enormous energy and inventiveness and outrage, that reflected an era when English, Welsh, Scottish, and Irish people found themselves in the midst of an expanding economy, lowering barriers to education, and the beginnings of the Industrial Revolution.

Poetry

It was during this time that poet James Thomson (1700–1748) produced his melancholy The Seasons (1728–30) and Edward Young (1681–1765) wrote his poem Night Thoughts (1742), though the most outstanding poet of the age is Alexander Pope (1688–1744). It is also the era that saw a serious competition over the proper model for the pastoral. In criticism, poets struggled with a doctrine of decorum, of matching proper words with proper sense and of achieving a diction that matched the gravity of a subject. At the same time, the mock-heroic was at its zenith and Pope's Rape of the Lock (1712–17) and The Dunciad (1728–43) are still considered to be the greatest mock-heroic poems ever written.[68] Pope also translated the Iliad (1715–20) and the Odyssey (1725–26). Since his death, Pope has been in a constant state of re-evaluation.[69]

Drama

Drama in the early part of the period featured the last plays of John Vanbrugh and William Congreve, both of whom carried on the Restoration comedy with some alterations. However, the majority of stagings were of lower farces and much more serious and domestic tragedies. George Lillo and Richard Steele both produced highly moral forms of tragedy, where the characters and the concerns of the characters were wholly middle class or working class. This reflected a marked change in the audience for plays, as royal patronage was no longer the important part of theatrical success. Additionally, Colley Cibber and John Rich began to battle each other for greater and greater spectacles to present on stage. The figure of Harlequin was introduced, and pantomime theatre began to be staged. This "low" comedy was quite popular, and the plays became tertiary to the staging. Opera also began to be popular in London, and there was significant literary resistance to this Italian incursion. In 1728 John Gay returned to the playhouse with The Beggar's Opera. The Licensing Act 1737 brought an abrupt halt to much of the period's drama, as the theatres were once again brought under state control.

Prose, including the novel

In prose, the earlier part of the period was overshadowed by the development of the English essay. Joseph Addison and Richard Steele's The Spectator established the form of the British periodical essay. However, this was also the time when the English novel was first emerging. Daniel Defoe turned from journalism and writing criminal lives for the press to writing fictional criminal lives with Roxana and Moll Flanders. He also wrote Robinson Crusoe (1719).

If Addison and Steele were dominant in one type of prose, then Jonathan Swift author of the satire Gulliver's Travels was in another. In A Modest Proposal and the Drapier Letters, Swift reluctantly defended the Irish people from the predations of colonialism. This provoked riots and arrests, but Swift, who had no love of Irish Roman Catholics, was outraged by the abuses he saw.

An effect of the Licensing Act of 1737 was to cause more than one aspiring playwright to switch over to writing novels. Henry Fielding (1707–1754) began to write prose satire and novels after his plays could not pass the censors. In the interim, Samuel Richardson (1689–1761) had produced Pamela, or Virtue Rewarded (1740), and Henry Fielding attacked, what he saw, as the absurdity of this novel in, Joseph Andrews (1742) and Shamela. Subsequently, Fielding satirised Richardson's Clarissa (1748) with Tom Jones (1749). Tobias Smollett (1721–1771) elevated the picaresque novel with works such as Roderick Random (1748) and Peregrine Pickle (1751).

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=English_literature

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk