A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

This article should specify the language of its non-English content, using {{lang}}, {{transliteration}} for transliterated languages, and {{IPA}} for phonetic transcriptions, with an appropriate ISO 639 code. Wikipedia's multilingual support templates may also be used. (September 2020) |

| Middle English | |

|---|---|

| Englisch English Inglis | |

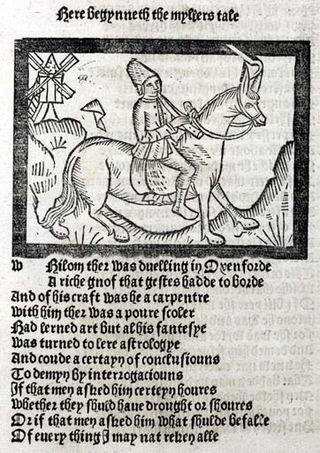

A page from Geoffrey Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales | |

| Region | England (except for west Cornwall), some localities in the eastern fringe of Wales, south east Scotland and Scottish burghs, to some extent Ireland |

| Era | developed into Early Modern English, and Fingallian and Yola in Ireland by the 15th century |

Early forms | |

| Latin | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | enm |

| ISO 639-3 | enm |

| ISO 639-6 | meng |

| Glottolog | midd1317 |

Middle English (abbreviated to ME[1]) is a form of the English language that was spoken after the Norman Conquest of 1066, until the late 15th century. The English language underwent distinct variations and developments following the Old English period. Scholarly opinion varies, but Oxford University Press specifies the period when Middle English was spoken as being from 1100 to 1500.[2] This stage of the development of the English language roughly followed the High to the Late Middle Ages.

Middle English saw significant changes to its vocabulary, grammar, pronunciation, and orthography. Writing conventions during the Middle English period varied widely. Examples of writing from this period that have survived show extensive regional variation. The more standardized Old English literary variety broke down and writing in English became fragmented and localized and was, for the most part, being improvised.[2] By the end of the period (about 1470), and aided by the invention of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg in 1439, a standard based on the London dialects (Chancery Standard) had become established. This largely formed the basis for Modern English spelling, although pronunciation has changed considerably since that time. Middle English was succeeded in England by Early Modern English, which lasted until about 1650. Scots developed concurrently from a variant of the Northumbrian dialect (prevalent in northern England and spoken in southeast Scotland).

During the Middle English period, many Old English grammatical features either became simplified or disappeared altogether. Noun, adjective, and verb inflections were simplified by the reduction (and eventual elimination) of most grammatical case distinctions. Middle English also saw considerable adoption of Anglo-Norman vocabulary, especially in the areas of politics, law, the arts, and religion, as well as poetic and emotive diction. Conventional English vocabulary remained primarily Germanic in its sources, with Old Norse influences becoming more apparent. Significant changes in pronunciation took place, particularly involving long vowels and diphthongs, which in the later Middle English period began to undergo the Great Vowel Shift.

Little survives of early Middle English literature, due in part to Norman domination and the prestige that came with writing in French rather than English. During the 14th century, a new style of literature emerged with the works of writers including John Wycliffe and Geoffrey Chaucer, whose Canterbury Tales remains the most studied and read work of the period.[4]

History

Transition from Old English

The transition from Late Old English to Early Middle English occurred at some point during the 12th century.

The influence of Old Norse aided the development of English from a synthetic language with relatively free word order to a more analytic language with a stricter word order.[2][5] Both Old English and Old Norse (as well as the descendants of the latter, Faroese and Icelandic) were synthetic languages with complicated inflections. The eagerness of Vikings in the Danelaw to communicate with their Anglo-Saxon neighbours resulted in the erosion of inflection in both languages.[5][6] Old Norse may have had a more profound impact on Middle and Modern English development than any other language.[7][8][9] Simeon Potter says, "No less far-reaching was the influence of Scandinavian upon the inflexional endings of English in hastening that wearing away and leveling of grammatical forms which gradually spread from north to south."[10]

Viking influence on Old English is most apparent in the more indispensable elements of the language. Pronouns, modals, comparatives, pronominal adverbs (like "hence" and "together"), conjunctions, and prepositions show the most marked Danish influence. The best evidence of Scandinavian influence appears in extensive word borrowings, yet no texts exist in either Scandinavia or Northern England from this period to give certain evidence of an influence on syntax. However, at least one scholarly study of this influence shows that Old English may have been replaced entirely by Norse, by virtue of the change from the Old English syntax to Norse syntax.[11] The effect of Old Norse on Old English was substantive, pervasive, and of a democratic character.[5][6] Like close cousins, Old Norse and Old English resembled each other, and with some words in common, they roughly understood each other;[6] in time, the inflections melted away and the analytic pattern emerged.[8][12] It is most "important to recognise that in many words the English and Scandinavian language differed chiefly in their inflectional elements. The body of the word was so nearly the same in the two languages that only the endings would put obstacles in the way of mutual understanding. In the mixed population that existed in the Danelaw, these endings must have led to much confusion, tending gradually to become obscured and finally lost." This blending of peoples and languages resulted in "simplifying English grammar".[5]

While the influence of Scandinavian languages was strongest in the dialects of the Danelaw region and Scotland, words in the spoken language emerged in the 10th and 11th centuries near the transition from Old to Middle English. Influence on the written language only appeared at the beginning of the 13th century, likely because of a scarcity of literary texts from an earlier date.[5]

The Norman Conquest of England in 1066 saw the replacement of the top levels of the English-speaking political and ecclesiastical hierarchies by Norman rulers who spoke a dialect of Old French known as Old Norman, which developed in England into Anglo-Norman. The use of Norman as the preferred language of literature and polite discourse fundamentally altered the role of Old English in education and administration, even though many Normans of this period were illiterate and depended on the clergy for written communication and record-keeping. A significant number of words of Norman origin began to appear in the English language alongside native English words of similar meaning, giving rise to such Modern English synonyms as pig/pork, chicken/poultry, calf/veal, cow/beef, sheep/mutton, wood/forest, house/mansion, worthy/valuable, bold/courageous, freedom/liberty, sight/vision, and eat/dine.

The role of Anglo-Norman as the language of government and law can be seen in the abundance of Modern English words for the mechanisms of government that are derived from Anglo-Norman: court, judge, jury, appeal, parliament. There are also many Norman-derived terms relating to the chivalric cultures that arose in the 12th century, an era of feudalism, seigneurialism, and crusading.

Words were often taken from Latin, usually through French transmission. This gave rise to various synonyms, including kingly (inherited from Old English), royal (from French, which inherited it from Vulgar Latin), and regal (from French, which borrowed it from classical Latin). Later French appropriations were derived from standard, rather than Norman, French. Examples of resultant cognate pairs include the words warden (from Norman) and guardian (from later French; both share a common ancestor loaned from Germanic).

The end of Anglo-Saxon rule did not result in immediate changes to the language. The general population would have spoken the same dialects as they had before the Conquest. Once the writing of Old English came to an end, Middle English had no standard language, only dialects that derived from the dialects of the same regions in the Anglo-Saxon period.

Early Middle English

Early Middle English (1100–1300)[13] has a largely Anglo-Saxon vocabulary (with many Norse borrowings in the northern parts of the country) but a greatly simplified inflectional system. The grammatical relations that were expressed in Old English by the dative and instrumental cases were replaced in Early Middle English with prepositional constructions. The Old English genitive -es survives in the -'s of the modern English possessive, but most of the other case endings disappeared in the Early Middle English period, including most of the roughly one dozen forms of the definite article ("the"). The dual personal pronouns (denoting exactly two) also disappeared from English during this period.

Gradually, the wealthy and the government Anglicised again, although Norman (and subsequently French) remained the dominant language of literature and law until the 14th century, even after the loss of the majority of the continental possessions of the English monarchy. The loss of case endings was part of a general trend from inflections to fixed word order that also occurred in other Germanic languages (though more slowly and to a lesser extent), and therefore, it cannot be attributed simply to the influence of French-speaking sections of the population: English did, after all, remain the vernacular. It is also argued[14] that Norse immigrants to England had a great impact on the loss of inflectional endings in Middle English. One argument is that, although Norse and English speakers were somewhat comprehensible to each other due to similar morphology, the Norse speakers' inability to reproduce the ending sounds of English words influenced Middle English's loss of inflectional endings.

Important texts for the reconstruction of the evolution of Middle English out of Old English are the Peterborough Chronicle, which continued to be compiled up to 1154; the Ormulum, a biblical commentary probably composed in Lincolnshire in the second half of the 12th century, incorporating a unique phonetic spelling system; and the Ancrene Wisse and the Katherine Group, religious texts written for anchoresses, apparently in the West Midlands in the early 13th century.[15] The language found in the last two works is sometimes called the AB language.

More literary sources of the 12th and 13th centuries include Layamon's Brut and The Owl and the Nightingale.

Some scholars[16] have defined "Early Middle English" as encompassing English texts up to 1350. This longer time frame would extend the corpus to include many Middle English Romances (especially those of the Auchinleck manuscript c. 1330).

14th century

From around the early 14th century, there was significant migration into London, particularly from the counties of the East Midlands, and a new prestige London dialect began to develop, based chiefly on the speech of the East Midlands but also influenced by that of other regions.[17] The writing of this period, however, continues to reflect a variety of regional forms of English. The Ayenbite of Inwyt, a translation of a French confessional prose work, completed in 1340, is written in a Kentish dialect. The best known writer of Middle English, Geoffrey Chaucer, wrote in the second half of the 14th century in the emerging London dialect, although he also portrays some of his characters as speaking in northern dialects, as in the "Reeve's Tale".

In the English-speaking areas of lowland Scotland, an independent standard was developing, based on the Northumbrian dialect. This would develop into what came to be known as the Scots language.

A large number of terms for abstract concepts were adopted directly from scholastic philosophical Latin (rather than via French). Examples are "absolute", "act", "demonstration", and "probable".[18]

Late Middle English

The Chancery Standard of written English emerged c. 1430 in official documents that, since the Norman Conquest, had normally been written in French.[17] Like Chaucer's work, this new standard was based on the East Midlands-influenced speech of London. Clerks using this standard were usually familiar with French and Latin, influencing the forms they chose. The Chancery Standard, which was adopted slowly, was used in England by bureaucrats for most official purposes, excluding those of the Church and legalities, which used Latin and Law French respectively.

The Chancery Standard's influence on later forms of written English is disputed, but it did undoubtedly provide the core around which Early Modern English formed.[citation needed] Early Modern English emerged with the help of William Caxton's printing press, developed during the 1470s. The press stabilized English through a push towards standardization, led by Chancery Standard enthusiast and writer Richard Pynson.[19] Early Modern English began in the 1540s after the printing and wide distribution of the English Bible and Prayer Book, which made the new standard of English publicly recognizable and lasted until about 1650.

Phonology

The main changes between the Old English sound system and that of Middle English include:

- Emergence of the voiced fricatives /v/, /ð/, /z/ as separate phonemes, rather than mere allophones of the corresponding voiceless fricatives

- Reduction of the Old English diphthongs to monophthongs and the emergence of new diphthongs due to vowel breaking in certain positions, change of Old English post-vocalic /j/, ?pojem= (sometimes resulting from the allophone of /ɡ/) to offglides, and borrowing from French

- Merging of Old English /æ/ and /ɑ/ into a single vowel /a/

- Raising of the long vowel /æː/ to /ɛː/

- Rounding of /ɑː/ to /ɔː/ in the southern dialects

- Unrounding of the front rounded vowels in most dialects

- Lengthening of vowels in open syllables (and in certain other positions). The resultant long vowels (and other preexisting long vowels) subsequently underwent changes of quality in the Great Vowel Shift, which began during the later Middle English period.

- Loss of gemination (double consonants came to be pronounced as single ones)

- Loss of weak final vowels (schwa, written ⟨e⟩). By Chaucer's time, this vowel was silent in normal speech, although it was normally pronounced in verse as the meter required (much as occurs in modern French). Also, nonfinal unstressed ⟨e⟩ was dropped when adjacent to only a single consonant on either side if there was another short ⟨e⟩ in an adjoining syllable. Thus, every began to be pronounced as evry, and palmeres as palmers.

The combination of the last three processes listed above led to the spelling conventions associated with silent ⟨e⟩ and doubled consonants (see under Orthography, below).

Morphology

Nouns

Middle English retains only two distinct noun-ending patterns from the more complex system of inflection in Old English:

| Nouns | Strong nouns | Weak nouns | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | |

| Nominative | -(e) | -es | -e | -en |

| Accusative | -en | |||

| Genitive | -es[19] | -e(ne)[20] | ||

| Dative | -e | -e(s) | ||

Nouns of the weak declension are primarily inherited from Old English n-stem nouns but also from ō-stem, wō-stem, and u-stem nouns,[citation needed] which did not inflect in the same way as n-stem nouns in Old English, but joined the weak declension in Middle English. Nouns of the strong declension are inherited from the other Old English noun stem classes.

Some nouns of the strong type have an -e in the nominative/accusative singular, like the weak declension, but otherwise strong endings. Often, these are the same nouns that had an -e in the nominative/accusative singular of Old English (they, in turn, were inherited from Proto-Germanic ja-stem and i-stem nouns).

The distinct dative case was lost in early Middle English. The genitive survived, however, but by the end of the Middle English period, only the strong -'s ending (variously spelt) was in use.[21] Some formerly feminine nouns, as well as some weak nouns, continued to make their genitive forms with -e or no ending (e.g., fole hoves, horses' hooves), and nouns of relationship ending in -er frequently have no genitive ending (e.g., fader bone, "father's bane").[22]

The strong -(e)s plural form has survived into Modern English. The weak -(e)n form is now rare and used only in oxen and as part of a double plural, in children and brethren. Some dialects still have forms such as eyen (for eyes), shoon (for shoes), hosen (for hose(s)), kine (for cows), and been (for bees).

Grammatical gender survived to a limited extent in early Middle English[22] before being replaced by natural gender in the course of the Middle English period. Grammatical gender was indicated by agreement of articles and pronouns (e.g., þo ule "the feminine owl") or using the pronoun he to refer to masculine nouns such as helm ("helmet"), or phrases such as scaft stærcne (strong shaft), with the masculine accusative adjective ending -ne.[23]

Adjectives

Single-syllable adjectives added -e when modifying a noun in the plural and when used after the definite article (þe), after a demonstrative (þis, þat), after a possessive pronoun (e.g., hir, our), or with a name or in a form of address. This derives from the Old English "weak" declension of adjectives.[24] This inflexion continued to be used in writing even after final -e had ceased to be pronounced.[25] In earlier texts, multisyllable adjectives also receive a final -e in these situations, but this occurs less regularly in later Middle English texts. Otherwise, adjectives have no ending and adjectives already ending in -e etymologically receive no ending as well.[25]

Earlier texts sometimes inflect adjectives for case as well. Layamon's Brut inflects adjectives for the masculine accusative, genitive, and dative, the feminine dative, and the plural genitive.[26] The Owl and the Nightingale adds a final -e to all adjectives not in the nominative, here only inflecting adjectives in the weak declension (as described above).[27]

Comparatives and superlatives were usually formed by adding -er and -est. Adjectives with long vowels sometimes shortened these vowels in the comparative and superlative (e.g., greet, great; gretter, greater).[27] Adjectives ending in -ly or -lich formed comparatives either with -lier, -liest or -loker, -lokest.[27] A few adjectives also displayed Germanic umlaut in their comparatives and superlatives, such as long, lenger.[27] Other irregular forms were mostly the same as in modern English.[27]

Pronouns

Middle English personal pronouns were mostly developed from those of Old English, with the exception of the third person plural, a borrowing from Old Norse (the original Old English form clashed with the third person singular and was eventually dropped). Also, the nominative form of the feminine third person singular was replaced by a form of the demonstrative that developed into sche (modern she), but the alternative heyr remained in some areas for a long time.

As with nouns, there was some inflectional simplification (the distinct Old English dual forms were lost), but pronouns, unlike nouns, retained distinct nominative and accusative forms. Third person pronouns also retained a distinction between accusative and dative forms, but that was gradually lost: The masculine hine was replaced by him south of the River Thames by the early 14th century, and the neuter dative him was ousted by it in most dialects by the 15th.[28]

The following table shows some of the various Middle English pronouns. Many other variations are noted in Middle English sources because of differences in spellings and pronunciations at different times and in different dialects.[29]

| Person / gender | Subject | Object | Possessive determiner | Possessive pronoun | Reflexive | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | ||||||

| First | ic / ich / I I |

me / mi me |

min / minen my |

min / mire / minre mine |

min one / mi seluen myself | |

| Second | þou / þu / tu / þeou you (thou) |

þe you (thee) |

þi / ti your (thy) |

þin / þyn yours (thine) |

þeself / þi seluen yourself (thyself) | |

| Third | Masculine | he he |

him[a] / hine[b] him |

his / hisse / hes his |

his / hisse his |

him-seluen himself |

| Feminine | sche / sho / ȝho she |

heo / his / hie / hies / hire her |

hio / heo / hire / heore her |

- hers |

heo-seolf herself | |

| Neuter | hit it |

hit / him it |

his its |

his its |

hit sulue itself | |

| Plural | ||||||

| First | we we |

us / ous us |

ure / our / ures / urne our |

oures ours |

us self / ous silue ourselves | |

| Second | ȝe / ye you (ye) |

eow / ou / ȝow / gu / you you |

eower / ower / gur / our your |

youres yours |

Ȝou self / ou selue yourselves | |

| Third | From Old English | heo / he | his / heo | heore / her | - | - |

| From Old Norse | þa / þei / þeo / þo | þem / þo | þeir | - | þam-selue | |

| modern | they | them | their | theirs | themselves | |

Verbs

As a general rule, the indicative first person singular of verbs in the present tense ended in -e (e.g., ich here, "I hear"), the second person singular in -(e)st (e.g., þou spekest, "thou speakest"), and the third person singular in -eþ (e.g., he comeþ, "he cometh/he comes"). (þ (the letter "thorn") is pronounced like the unvoiced th in "think", but under certain circumstances, it may be like the voiced th in "that"). The following table illustrates a typical conjugation pattern:[30][31]

| Verbs inflection | Infinitive | Present | Past | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participle | Singular | Plural | Participle | Singular | Plural | ||||||

| 1st person | 2nd person | 3rd person | 1st person | 2nd person | 3rd person | ||||||

| Regular verbs | |||||||||||

| Strong | -en | -ende, -ynge | -e | -est | -eþ (-es) | -en (-es, -eþ) | i- -en | – | -e (-est) | – | -en |

| Weak | -ed | -ede | -edest | -ede | -eden | ||||||

| Irregular verbs | |||||||||||

| Been "be" | been | beende, beynge | am | art | is | aren | ibeen | was | wast | was | weren |

| be | bist | biþ | beth, been | were | |||||||

| Cunnen "can" | cunnen | cunnende, cunnynge | can | canst | can | cunnen | cunned, coud | coude, couthe | coudest, couthest | coude, couthe | couden, couthen |

| Don "do" | don | doende, doynge | do | dost | doþ | doþ, don | idon | didde | didst | didde | didden |

| Douen "be good for" | douen | douende, douynge | deigh | deight | deigh | douen | idought | dought | doughtest | dought | doughten |

| Durren "dare" | durren | durrende, durrynge | dar | darst | dar | durren | durst, dirst | durst | durstest | durst | dursten |

| Gon "go" | gon | goende, goynge | go | gost | goþ | goþ, gon | igon(gen) | wend, yede, yode | wendest, yedest, yodest | wende, yede, yode | wenden, yeden, yoden |

| Haven "have" | haven | havende, havynge | have | hast | haþ | haven | ihad | hadde | haddest | hadde | hadden |

| Moten "must" | – | – | mot | must | mot | moten | – | muste | mustest | muste | musten |

| Mowen "may" | mowen | mowende, mowynge | may | myghst | may | mowen | imought | mighte | mightest | mighte | mighten |

| Owen "owe, ought" | owen | owende, owynge | owe | owest | owe | owen | iowen | owed | ought | owed | ought |

| Schulen "should" | – | – | schal | schalt | schal | schulen | – | scholde | scholdest | scholde | scholde

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Chancery_Standard Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Analytika

Antropológia Aplikované vedy Bibliometria Dejiny vedy Encyklopédie Filozofia vedy Forenzné vedy Humanitné vedy Knižničná veda Kryogenika Kryptológia Kulturológia Literárna veda Medzidisciplinárne oblasti Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy Metavedy Metodika Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok. www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk |